Pixley Seme was born on 1 October 1881 in Natal, the son of Isaka Sarah (nee Mseleku) Seme. Little is documented of his early life as a primary school pupil and teenager. He obtained his primary school education at the local mission school where the American Congregationalist missionary, Reverend S. C. Pixley, took an interest in him and arranged for him to go the Mount Hermon School in Massachusetts in the USA.

Seme did his BA degree at Columbia and then went to Oxford University where he completed a degree in Law. He was called to the bar at the Middle Temple in London before returning to South Africa on the eve of the creation of the Union of South Africa in 1910.

His memorable speech at Columbia University in 1906 on “The Regeneration of Africa” won him the University’s highest oratorical honour, the George William Curtis medal. The speech was circulated widely in South Africa and revealed Seme’s remarkable way with words. While in London in 1909, Seme followed deliberations about the Union of South Africa Bill (1909) that proposed a framework for the establishment of the Union of South Africa. His reaction to this development is articulated in another authoritative view on the future of South Africa.

“The Native Union” is a document that mapped out a strategy for African people in reaction to developments designed to exclude them from participating in mainstream political institutions and which sought to regulate their access to land and certain categories of employment, particularly in the mines. The document also reflects Seme’s insight into forms of resistance to the impending political dispensation. Though not stated explicitly in the document, Seme seems to have been of the opinion that the Bambatha Rebellion type of response to the emerging Union was atavistic. This implied a need for the creation of a Union-wide political movement that would counter the emerging segregationist system of government.

More than any of the leading personalities of the time, Seme is considered the founder of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC), the precursor of the ANC. Not only did he conceptualise the form and structure of the movement but he also facilitated the founding of the SANNC in Bloemfontein in 1912. At the founding Congress Seme delivered the keynote address, an appeal for symbolic and material support for the new formation. And when voting began for the position of president, Seme proposed that John Langalibalele Dube be elected.

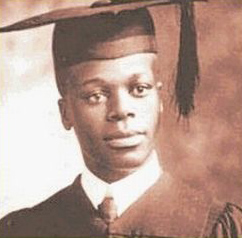

Pixley ka Isaka Seme on the occasion of his graduation from Colombia University with a BA Degree in 1906.

Pixley ka Isaka Seme on the occasion of his graduation from Colombia University with a BA Degree in 1906.

The SANNC needed funding if it was to fulfill its function. In the context of the time, chiefs were the main source of potential funding. This critical factor is rarely appreciated in considerations of the fortunes and misfortunes of the SANNC in the first decade of its existence. Existing accounts of what is widely considered a dismal performance by the SANNC in its first decade often fail to reflect on the impact of the lack of funds on the organisation. Seme himself, considered the most persuasive to garner the support of the chiefs, was a logical choice for the position of Treasurer-General, a fact that must be taken into account in any examination of the SANNC’s effectiveness and funding environment.

The matter assumes greater significance when viewed in the context of Seme’s financial woes during the decade. It appears that “though he became Congress’s first Treasurer-General, he was always in financial difficulties. Various ventures on which he embarked failed, including buying farms in what was then the Transvaal.” This observation seems to give an indication of just how handicapped, financially, the SANNC was in the 1910s. This was decades before its successor, the ANC, created a massive capacity for attracting funding, with serious implications for organizational core values.

The Founder’s misfortunes in the 1910s were mirrored by those of the SANNC. For much of the 1910s, as the Union of South Africa leapt from one crisis to the next, the SANNC was unable to mount a serious challenge to the segregationist regime. The Land Act of 1913, intended to deny African farmers the only form of access to land they had since the conclusion of wars of conquest in the 1860s and 1870s, went unchallenged. The only memorable response to it was Sol Plaatje’s book Native Life in South Africa, which condemns the inhumanity of the legislation, and a SANNC delegation to London that returned unfulfilled. Significantly, this delegation did not include Seme.

During this time Seme set up a newspaper, Abantu-Batho. Ambitious though this project proved to be, it was an ingenious way of drawing African people, its target audience, to the political discourse that impacted on their lives. Seme’s response to the Land Act has not been recorded.

The outbreak of World War I is yet another turning point that throws the spotlight on the SANNC under Dube’s presidency. Among Afrikaners, the war provoked the emergence of two groups committed to the politics of secession: the South African National Party (SANP) under JBM Hertzog, and the Anti-War rebellion led by Koos de la Rey and others. The two Afrikaner formations were opposed to the war, expressing resentment at having to fight what they saw as a British Imperial War against Germany, a power they had had an alliance with during the South African War of 1899 to 1902.

.jpg) Pixley Ka-Isaka Seme, a leading figure at the launch of the South African Native National Congress, later renamed the African National Congress (ANC).

Pixley Ka-Isaka Seme, a leading figure at the launch of the South African Native National Congress, later renamed the African National Congress (ANC).

On the other hand, in what appeared to have been a strategic positioning, the SANNC supported the war effort in the hope that when it ended, the British would show appreciation by intervening on their behalf. Uncharacteristically, during this momentous period in South African history, Seme did not articulate a view that would captivate as well as he did in 1906 and 1909/10. There is nothing of the calibre of his thoughts on African regeneration or the Native Union reported at the time of the war. Seme instead continued practising law, and following the failure of the 1914 delegation, the SANNC seemed to descend into inertia.

It was only after 1917 that the SANNC once again made its presence felt. Its provincial structure, the Transvaal SANNC, became deeply involved with two strike actions that paralysed the city of Johannesburg. First it was the mineworkers’ strike of 1918 over low wages. In 1919 sanitary workers went on strike in what became known as the “bucket strike”. The Transvaal SANNC, under Sefako Makgatho, who was also President General of the SANNC, became involved with both strikes. Historians agree that this marked the first attempt at making the SANNC a mass-based organization. It is not clear whether Seme supported Makgatho on the direction in which he seemed to be taking the SANNC, but it is significant that in the 1930s it was Makgatho’s friendship with Seme that secured for him the presidency of the Transvaal ANC. By 1920, Seme’s star was on the wane.

Early in the 1920s Seme had an opportunity to revive his career. He served as legal counsel for the Swazi Regent in a dispute with the British government. His knowledge of British law, having studied at Oxford, made him the logical choice for the task. However, the outcome of the case was disastrous for Seme – he lost the case on appeal at the Privy Council and returned to South Africa. The case seemed to have left him devastated, and “he began drinking to excess, and before the decade was over had been involved in an automobile accident when drunk”. He was subsequently struck off the roll of attorneys. It is possible that these developments left Seme despondent and without any appetite for political involvement.

In 1923, under Makgatho’s presidency, the SANNC changed its name to the African National Congress (ANC). A year later at an elective Congress, Makgatho was voted out of office and replaced by ZR Mahabane. The Mahabane presidency was marked by intense ideological debates within the ANC and the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) about the primacy of the National Question over the class struggle, which aimed to bring an end to capitalist exploitation.

Yet again, Seme’s contribution to these debates is sorely missed, remaining unrecorded. The outcome of this contest at the level of ideas seems to have been settled in favour of the socialist faction within the ANC. In 1927 the ANC held an elective Congress and a candidate wedded to the socialist/Marxist doctrine was elected the new President General. JT Gumede was a committed socialist when he became leader of the ANC and sought to steer the movement in that direction, but he was opposed by some of the ANC’s stalwarts, including former presidents Mahabane and Makgatho.

It was during this strife that Seme is seen making a return to politics. He joined with the Nationalists, who were opposed to the socialist position promoted by Gumede. Relations between Nationalists and Socialist broke down irretrievably during 1929, leading to Gumede being unseated as President General. Seme seems to have recovered significantly from his woes of the previous decade, and in the elective Congress of 1930 he was elected to the position of President General.

Seme’s presidency is often associated with the demise of the ANC in the first half of the 1930s. It is argued that his failure to lead was largely the reason for the ANC’s sagging fortunes. Indeed, during the early 1930s the ANC’s following in urban and rural areas was at its lowest, compared with earlier decades. In the rural areas, particularly in areas dominated by white commercial agriculture, the Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICU) had upstaged the ANC throughout the1920s, mobilizing African sharecroppers and labour tenants against white landowners keen to exploit their labour. In the urban areas, particularly on the Witwatersrand, the CPSA had upstaged the ANC and enjoyed a sizeable following. The ICU and CPSA had established themselves while Seme’s two immediate predecessors led the Congress.

Seme became President General in the midst of the Great Depression, a period that threw up challenges that would have overwhelmed even the most capable of leaders. It is thus unfair to argue that Seme stood by as conditions in the ANC deteriorated. On the contrary, he tried to restructure the ANC in a bid to make it more responsive to the prevailing political circumstances.

The CPSA was particularly vibrant in local communities in townships across the country. CPSA branches became formidable opponents in Advisory Councils where they contested regular elections with civic structures, enjoying grassroots support. This was particularly true in Johannesburg’s municipal townships – in Orlando and the Western Native Township the CPSA contested elections and established itself as a significant role player in local politics.

Seme proposed organizational restructuring of the ANC at regional level, dissolving provincial congresses and subdividing the national body into 11 regional congresses in place of the four provincial congresses. These proposals incensed the relatively powerful Transvaal ANC, which had always been very influential in determining and shaping policy directions. A faction of the Executive Committee of the Transvaal ANC, led by Kgatla chiefs, accused Seme of attempting to undermine them to establish an Nguni hegemony within the organization. Curiously, Seme was supported in his reorganization by the President of the Transvaal ANC, Makgatho. In the process, Makgatho alienated himself from some members of the anti-Seme faction in the Transvaal ANC Executive Committee.

The feud between Makgatho and the opposing faction in the Transvaal ANC from 1932 ended in mid-1933 when Makgatho was voted out of office. This led to a split in the Transvaal ANC, with one side recognizing Makgatho as president and the other a new candidate. For more on this feud and how it was resolved click here.

Seme was becoming increasingly unpopular, with calls for his removal reaching a crescendo after the removal of Makgatho as President of the Transvaal ANC in 1934. In 1937 Seme was replaced by Mahabane, who was ready for a second stint. (For more on this click here)

This marked the end of Seme’s contribution to politics, and he returned to his law practice as his licence had been restored. For much of the 1940s he worked as an attorney with offices in downtown Johannesburg, and during this time he became Anton Lembede’s mentor. But the new generation of ANC leaders, mainly those in the Youth League, considered Seme as rather conservative. Seme died in 1951.

Conclusion

Seme’s memorable speech at Columbia University in 1906 earned him the Order of Luthuli in Gold in 2006, conferred by then president Thabo Mbeki. This gesture seemed to be at variance with the ANC’s perspective on Seme’s role in the history of the liberation struggle. Earlier, the ANC appeared to be airbrushing Seme out of the liberation history discourse precisely because he was perceived to have presided over the organization when it went through an unprecedented decline. But Seme could also be considered the founder of the ANC in ways that no other leader of the ANC could.