Related Collections from the Archive

From the book: Working Life - Factories, Township and Popular Culture 1886 - 1940 by Luli Callinicos

Topic

So far, this feature has described how the development of a racial capitalist society affected the lives-working people in the factories and at home. This section looks at how these first generation workers acted to change the world they found themselves in. We shall see how they coped with riding poverty in those years and how, day-by-day and year-by-year, they created a way of life —a culture — through which they survived in the strange and hostile world of the city.

The shock of the city

‘Fifty years I have lived in the city . . .. In the city I found people very unkind and unsociable. I sneaked unconsciously into it. I became one of it.’

For most new workers fresh from the land, the noisy, pushy city came as a deep shock. People were crowded together in large numbers, yet they were strangers to each other. A newcomer could pass hundreds of people in the street and not one would give a greeting or even a smile. The city was a cold place, and no one seemed at all interested in the problems of a lonely and homesick person.

The support and family care of the homestead in the countryside were gone. In the city, newcomers had no homes. They lived in rented rooms, and even slept in rented beds. All comforts, entertainments, even rest itself, became items to be paid for with money — and for workers, there was very little of that. In the workplace too, supervisors and managers seemed to care very little for the feelings of workers — production and profit were the aim, with as little reward for the worker as possible.

The new worker was forced to live a new and strange way of life, suited to the new form of production introduced by the industrial capitalist system. The newcomer had to learn to value new ways, and to drop some of the old ways that did not help people to survive in the city.

Exactly how did workers live their lives away from the work place — the hours when they had to renew and prepare themselves for another working day in between working shifts?

In this respect the labour of women was very important — for women traditionally maintain the homes where workers find shelter, food, rest and relaxation.

The arrival of women

The first section in this feature described how worker came at different times and for different reasons to find work in the towns. For example, amongst whites the women tended to leave the rural areas first to se work in the towns.

Black women, on the other hand, tended to come later —their labour was needed for the homesteads to continue. For many years, therefore, black workers in towns were mostly men, and they had to develop a male way of life — hard and unnatural, because they were deprived of the company of women and children.

But in the 1920s and 1930s many black women, especially young women, began to arrive on the Ran in larger numbers. Many black people of both sexes were forced to make their way to the towns at that time. The move to the towns was accelerated by the removal of many black farmers from the white-own farms after the 1913 Land Act and the droughts and cattle-diseases of that time, as well as the rapid development of industries on the Rand during World War I. Soon after the women, came children and homes. A more normal living pattern began to develop amongst the new workers on the Rand.

Economic conditions of workers

But in order to understand the culture of workers and they lived at that time it is important to look at their economic situation. We have also seen how the higher wages and privileges of the established craft workers in South Africa separated them in many ways from the low-paid industrial workers, especially black workers.

The new unskilled workers made up the cheap labour force, and poverty dominated their way of life. The chart in The Struggle for Survival shows how inadequate the average black worker’s wage if he was lucky enough to be constantly employed. And for African workers, the ‘Laws for Non-Europeans Only’ made town life more expensive and dangerous. African workers lived in a nightmare world of passes, curfews and controls, in which it was easy to be flung in jail or lose a job and hard to find a one. Hardship was also the lot of thousands of y white women workers on the Rand, as A Garment Worker’s Budget.

Adding to the wage

For black workers in particular the wage was nowhere enough to live on. How then did they manage to survive? There are different answers to this question —first is that many did not survive, especially the children. Death came from poverty undernourishment, poor water supplies and crowded, unhealthy living conditions. It came from inadequate medical care, from danger at the work-place, from violence in the night.

Another answer was the support of the reserves. As described in Children of the Ghetto, more than half of the children born to black town women were sent home, to the land. There they could get moral training and live in more healthy surroundings. The economy of the reserves therefore continued to support the children of many women working in the towns.

A third explanation is that workers and their families found extra ways of adding to, or supplementing, their meagre wages. The supplementary wage was provided mainly by the women — the wives and daughters of workers. White women, as we have seen, were employed in the 1920s and 1930s at low wages in the factories. Black women were able to make some extra money taking in washing or as full-time domestic workers.

The informal economy

But mostly workers supplemented their income in informal ways — that is, they found other ways than wage labour of making extra money. To do this they often had to break the laws, as Crime and Punishment and Brewers in the Towns. A great deal of this informal income was earned by women.

In the homesteads of the countryside women were a very important part of the economy — in the town they were no different. A woman’s earnings often made the difference between survival and starvation. In those early years, most black women were newly arrived from the countryside — few spoke English, the language of the ruling class in the towns — and they had little knowledge of the ways of whites. Their economic activity was directed mainly towards their own people. Often they used the skills they had learnt at home to make things and then sold their products to neighbours or fellow black workers.

Some women sewed, others hawked in the streets or outside the compounds, as the pictures in this section show. In addition, a great many women brewed beer, which was profitable but illegal. Many women, white as well as black, got extra income from prostitution — a natural result of poverty in town, where men outnumbered women.

Children were part of the informal economy too. Children of the Ghettoes describes how children helped their mothers in the home; they also delivered washing, earned tips carrying goods at the market, collected and washed bottles, sold newspapers, caddied on golf courses, and begged — or stole.

A number of men, too, were able to supplement their wages in the informal economy, slipping in and out of wage labour, or earning extra money part-time— for instance, as cobblers repairing shoes for people in the neighbourhood. A few were able to survive without entering the formal economic system at all. There were, for instance, full-time musicians who earned a living playing for parties and concerts in the townships. There were also some church ministers and diviners who managed to survive by offering their services to their own people— Christianity and the Ancestors. Crime and Punishment deals with those who turned a life of organised crime. Others produced goods at home, such as furniture, which they were able to sell dealers or directly to people in their rooms and houses.

But in general, these activities were not profitable enough to earn them a full-time living and most black families lived in gross poverty.

Changing jobs

In the l920s and 1930s even black school teachers at other professional people suffered from miserably low wages. Furthermore, their jobs were not always sect and many were obliged to join the working class, or the ranks of the unemployed, at least part of the tin.

For example, author Modikwe Dikobe started his working life in the 1930s as a newspaper-seller for the Central News Agency (CNA), often sleeping in the CNA compound. Then he became a hawker, selling religious pictures:

'My stock consisted of best-selling pictures: Elijah, Crucifixion, Moses on Mount Sinai and a dozen others.’

As a hawker he did not consider himself a worker,

‘I was of another class. I couldn’t have the same, sympathy as a worker [who] wakes up and complains of small wages and so on. I had to complain to myself that business was bad, like any other businessman who says “business is bad.'

In 1942, during his time as a hawker, Dikobe also me the secretary of the Alexandra squatters’ resistance movement. His hawking business was neglected and failed. Dikobe then took employment as clerk in a furniture factory. In later years, he was by a domestic servant, a night watchman and a municipal clerk. Dikobe, like thousands of others, weaved in and out of self-employment, white-collar (such as office work and teaching) and the lowest-workers’ jobs — anything, which would keep him his family going.

The melting pot

The crowded working-class areas became ‘melting ‘of humanity — they were places where people from all over the country and even other parts of the world came together, pulled by the industrial revolution created by the mines. The newcomers worked in the same shops and factories and they lived in the same housing districts. The working-class districts such as Vrededorp and Doornfontein housed both black and white workers, as well as those looking for work, the self-employed, and the workless of all nationalities.

In addition different black classes lived together —black workers, the unemployed, traders and professional people were all squashed together in one suburb or township because of the desperate shortage of black housing. And as we saw, the 1923 Urban Areas Act, which discriminated against blacks, made the housing problem worse.

In the towns Africans from many different chiefdoms were brought together, especially on the Rand. Whether they liked it or not, they were forced to mix, and in time many traditional customs of particular chiefdoms fell away or merged as men and women from different parts of the country set up home together and raised families in town. As early as 1933, for example, a study of a yard in Doornfontein showed that more than half of the hundred couples living there were ‘mixed’ unions.(On the other hand, divisions amongst blacks did not disappear. Indeed, in many cases, their differences were actually exploited by both state and management. These differences are discussed later in this section.)

The problems of people caught between the customs of country life and the needs of the city are described powerfully in Modikwe Dikobe’s The Marabi Dance. Extracts from the feature illustrate the changing patterns of marriage and the family in the town.

The changing family pattern

In the towns, smaller families became common. Often the family unit did not include grandparents and other relatives. Sometimes there was only one parent. And as we noted earlier, many children lived in the rural areas away from their parents. Few black town men had more than one wife in the same household — the housing shortage, lack of space and women’s resistance prevented that. On the other hand, there were many desertions by the men. Fewer couples were married traditionally — a town couple would often decide to live together, but without lobola women were without protection. Modikwe Dikobe has described the new living patterns:

‘Men and women were just living together because of their offspring . . . - Many such marriages occurred in Prospect Township, Pimville, Doomnfontein, Vrededorp and Sophiatown in Johannesburg and Marabastad in Pretoria. In Pretoria it was known as saambly, in Johannesburg vat en sit. One does not find saamblys in country life. There every home is out of bogadi.’

Usually there were economic reasons for vat en sit. A man and woman would have to pool their money together to survive. Dispossessed of land and cattle they could seldom afford to save up for a lobola marriage. But these unofficial living arrangements were unsettling for the children:

‘The upbringing of children whose parents lived an unmarried life was disturbing. They [the children] regarded themselves as fatherless . . .. Their education was retarded. They lived in two worlds: city and country. They were misfits in both.’

With the upheaval of the removals from the slumyards to the ghettoes or locations, many more families split up. In just one yard for example, 23 out of 43 families were separated. In most cases, the men went to live in hostels, while the women and children went home to their mothers. Other families sent the children home, while the mother and father found separate live-in jobs such as domestic or municipal work. Modikwe Dikobe remembered the hard decisions that had to be made: ‘In bed a woman and husband squabbled. Bogadi [lobola] was not paid. The children were not the man’s.

Next door a compromise was reached:

'Pay by installment, marry by native commissioner and forge a bogadi receipt.” In the third door mutual agreement is completely broken. The woman goes back to her old missus, the man to Wemmer Barracks.’

In the rural areas, too, many families were abandon by migrant worker fathers who set up new household in the towns and forgot their duties to their families home. There were many family tragedies and heartaches as a result of industrialisation and the migrant labour system.

Resistance to town life

A location outside a small town

A location outside a small town

But there were also many migrant workers who valued their traditional way of life as laid down by their ancestors, and tried to protect it. They resisted the town way of life. These migrant workers saw migrant labour as necessary to help build up the umzi — the homestead. Wage labour was a time away from home like military service — but men should return home soon as it was over, while women should avoid leaving the homestead at all.

In town, these men preferred to live in hostels and mix only with their own group — their own network ‘home boys’. In their spare time they went drinking the shebeen of a woman from their own chiefdom. They tried not to get tied up with town women. Town was the place of the white man, they believed. They tried not to give in to ukurumsha (speaking English and adopting white ways and customs).

‘There is nothing I like about whites or their way of life’, said one such migrant. And another declared: ‘I not one of those Xhosa who try to ape the white manners I only want to appear what I am: a real Xhosa.'

Usually this feeling was strongest in migrants from reasonably well-off homesteads who were still living in their chiefdoms with enough land and cattle to continue that way of life. They were independent enough to resist of industrialisation.

But gradually, as the land became steadily more overcrowded, more and more people – women as well as men – were pushed to the towns in search of a way of a supplementing their subsistence in rural areas. In 1920s and 1930s, many settled townspeople still had very close ties with the land – for as we have seen, the reserves were helping to support them. Nevertheless the making of an urban people, dispossessed and cut off from the land, had already begun. By 1936 nearly half of the town workers had deserted the white farms, and so had no land of their own anyway, while another 29 percent were permanently settled in the towns.

A racially divided society

In this feature we have noted a number of times that South Africa was racially defined society in which people were judge the colour of their skin. This attitude was a legacy of colonial times, when white settlers had to justify their taking of the land claiming to bring civilization and Christianity to an ignorant and backward black people. Racism continued to flourish in industrial times – indeed capitalism profited from racism cultivating a massive cheap black labour force, as described in Gold and Workers.

Racism was deep in the consciousness of nearly every South African. In the writings and saying of both blacks and whites at that time we find constant references to deferent race and language groups. Black writers would sometimes write in a belittling way about Coloureds, Indians, and Chinese – and bitterly against whites; while even the most liberal whites were riddled with race prejudice.

Amongst the whites themselves prejudices against other white groups flourished as White Working Class Culture shows – the English looked down on the Afrikaners and most immigrants, while many Afrikaners resented the high-handed behaviour of the English, and as worker were threatened by cheap black labour. And in the 1830s, anti- Semitism or anti-Jewish attitudes reached their peak in South Africa with the rise of German Nazism, which had a significant influence on the development of Afrikaner nationalism at the time.

Amongst blacks themselves divisions continued, as we have already noted. Arriving on the Rand at different times, from different regions, and for different reasons, different groups of blacks had different working and living experiences. Others, through their ‘home-boy’ networks, entered domestic service, worked for the municipality as construction labourers, or entered some other occupation monopolised by a particular group. Some arrived later than others — perhaps because the dispossession of their land (or the decline of their means of living off the land) took place at a later stage, or because they were women. Some town communities were at first comprised of groups from particular regions or chiefdoms, while new ‘layers’ of people would move in as tenants, without having homes of their own.

Those who had left the white-owned farms settled into urban life quite quickly, for they had little to go back to; others went to town as migrant workers who intended to return to the countryside, and tried to hold themselves aloof from urban life styles.

Black society, although largely poor, did not therefore consist of a uniform mass of people. There were many and complex differences amongst blacks because of their different origins, as well as their different experiences and jobs in town. These differences affected the ways of life they adopted.

Race and class

Racism and division were a part of everyday life. The society — encouraged by the state, the schools, the press, the church, and employers — had created a racial world in which people were expected to behave according to the colour of their skin as well as the class they belonged to. Race therefore cut across class lines —most workers thought of themselves first as blacks or whites, and not foremost as workers.

Nevertheless, as this feature has also shown, there were times in the l920s and 1930s when blacks and whites were able to overcome some of their differences and their racial consciousness. They sometimes cooperated as productive workers labouring side-by-side in the factories and living in the same neighbourhoods.

But as the standards of the white workers improved rapidly through the government’s welfare policies of education, housing and protected jobs, more and more whites turned away from organised cooperation with black workers and identified with the culture of the white middle-class which they hoped to join. During and after World War II thousands of whites moved wards to become ‘labour aristocrats’ and supervisors. Most of them left the world of poverty and resistance behind.

Ruling and leading

Where before, as in 1922, the government had imposed its rule on white workers by force, by the late l930s white political parties, the press, the radio, the church and the schools led the way in shaping the attitudes the white working class. Social workers and the welfare system kept a watchful eye on those who fell by the wayside. As the standard of living of white workers proved they began to feel they had more control over their lives. They tended to see their new-found security the proof and reward of their racial ‘superiority’ as whites.

The voices of the black working population, on other hand, went largely unheard. Black workers never accepted the white ruling-class view of society. But they lacked the power to resist successfully the wages and poverty, the racist laws, the overcrowding and control to which they were subjected in slumyard and location.

Nevertheless, out of this world black workers created a new and thriving culture. The newcomers were no completely controlled by the new industrial society. They were able to respond in creative and vigorous ways, which surprised both the employers and the authorities. The workers had their own needs and developed their own way of life.

Black industrial life was born out of necessity. In hostile world blacks lived in, protest and resistance became necessities for survival. Black townspeople to struggle for a roof over their heads, for food, for education, for rest and relaxation. All these activities became issues, or sites of struggle.

The culture of survivalIn those first years of town life, most people developed a culture of survival. Just managing to live took all their time and energy, and it was only later that they began to organise and demand fair wages and decent living conditions. The black workers’ culture of survival — the informal economy, crime (sometimes against the community), the sharing of resources through stokvel groups, the making of money from selling drink to black workers — subsidised the wag the black worker.

The culture of survival

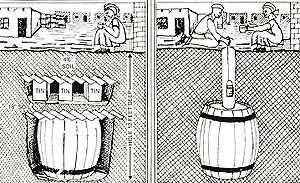

These are sketches that show a cunning manner in which liquor is buried

These are sketches that show a cunning manner in which liquor is buried

The culture of survival therefore had contradictions— that is, effects that went against its aims. The very success of the workers in finding other ways of supplementing their tiny incomes enabled employers to carry on paying starvation wages. Employers knew somehow black workers were surviving, and that their labour would thus continue to be available. So, although the employers decried the way of life of the lowest-paid workers and the poor, and although Idle-class liberals expressed their concern about the conditions prevailing, the culture of survival enabled employers to hold onto greater profits and build up their business enterprises.

Changing culture

In the course of these struggles, however, workers’ culture was constantly in the making, always changing, shifting according to the situations in which working class and middle-class people found themselves.

For or example the early white working-class literature did not develop. It gradually became lost and forgotten, as white workers became supervisors with the re-organisation of production after World War II. Instead of the literature of workers, their school-going children were taught the poetry, plays, novels and history of the middle class. It was as whites had never been members of a struggling and underpaid working class. That period was like a bad dream — it was embarrassing and best forgotten.

As for black workers, they were only just beginning form political and worker organisations to fight for re control over their lives — and at first only a tiny minority belonged to organisations. But in the years to come many changes would take place — for employers, the manufacturing industry was to grow and re-organise its production; for black rural families the reserves were able to supply less and less subsistence. As a result of both of these developments, the number of black workers was to grow rapidly in the towns and more organised forms of resistance would develop —both in the crowded townships and ghettoes, and in the factories.

The culture of working people depended on the conditions they found themselves in, but also on the people themselves. It depended on political factors, on the economy, and on the society as a whole. But it also depended on the way people used their own experience, their creativity and their wits to respond to this society. In the years to come, there were to be increased struggles and hardships, but out of these a richer and constantly growing culture would take shape.