Cameroon is sometimes referred to as a “true African crossroads” not only because of its geographical position, but also because of the country's great variety of ethnic groups and spoken languages [i]. To this end Cameroon can in many ways be considered a microcosm of the history of the African continent.

Before the colonial period, Cameroon was made up of a variety of different kingdoms and villages [ii]. In 1884 the area became a German colony and after the First World War it was divided between France and Britain [iii]. In 1960 the country was formalised into the Republic of Cameroon, when it gained independence from France [iv]. In 1961 the Federal Republic of Cameroon was formed when the British-controlled areas elected to join the Republic of Cameroon to become one nation [v].

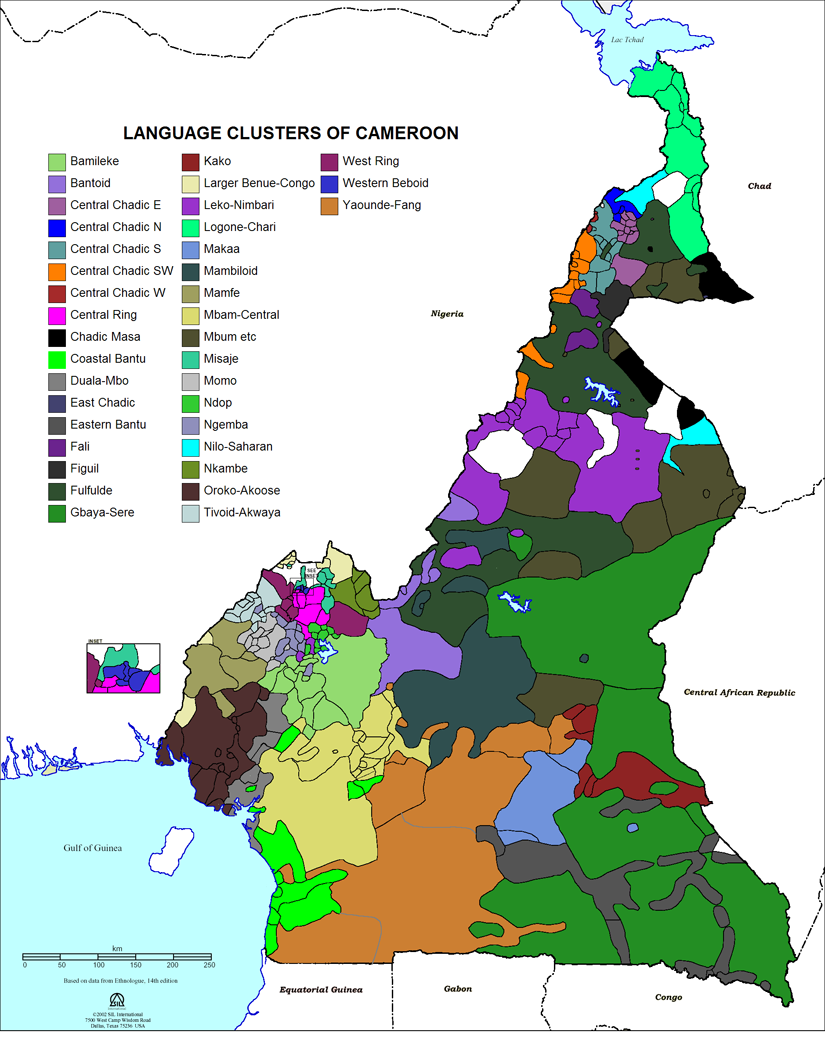

A map showing the various languages spoken in contemporary Cameroon. Image source

A map showing the various languages spoken in contemporary Cameroon. Image source

From the time of independence in 1960 right up until 1982, the country was ruled by Ahmadou Ahidjo [vi]. During his rule the country experienced a large degree of stability as well as economic development. However, with the election of current president Paul Biya in 1982 [vii] there has been a decline in the economic prosperity that ordinary Cameroonians became accustomed to under President Ahidjo. This is due to Paul Biya’s programmes of economic liberalisation [viii], implemented under the structural adjustment programs (SAPs).

Early History of Cameroon

The country now called Cameroon was never a unified entity prior to European colonisation [ix]. It was inhabited by a large variety of peoples of varying histories who spoke a variety of languages [x]. It is likely that the Baka people were the earliest inhabitants of Cameroon, and some [xi] speculate that they migrated to the area in around 50 000 BCE. Most of the territory was then organised into small, decentralised villages, and the central location of Cameroon meant that the area experienced a continuous flow of migration.

The area known as the Cameroon grassfields in the north-west of the country was densely populated from around 4 000 BCE [xii], and was made up of villages and states with populations ranging from 200 to 60 000 inhabitants [xiii]. Agriculture was the most common form of subsistence on the grassfields, yielding particularly the cultivation of Yams and the extraction of palm oil [xiv]. Palm oil was grown on the periphery of the grassfields and was used in trade with various people living in the central parts [xv], and the trade stimulated a certain level of specialisation in economic production. The central part of the grassfields was utilised for farming root vegetables as well as livestock [xvi], although the inhabitants of the grassfields also produced various craft items that were used for trade [xvii]. The high level of trade and specialisation resulted in the emergence of more densely populated areas which, from its inception, saw the dawn of more centralised kingdoms in the region [xviii].

Lake Nyos in the Cameroon grassfields. In 1986 a natural gas leak caused the death of around 1800 inhabitants of the area Image source

Lake Nyos in the Cameroon grassfields. In 1986 a natural gas leak caused the death of around 1800 inhabitants of the area Image source

The Emergence of Centralised Kingdoms

One of the earliest Kingdoms in Cameroon was founded by the Sao people in around 500 CE and was located on the shores of Lake Chad [xix]. In another part of the country - and about 800 years later - several kingdoms were formed in the abovementioned Cameroonian grassfields [xx]. The Kingdoms of Bamum, Bamileke, Nso' and Bafut were located in the north-western parts of Cameroon [xxi], and were all formed between the 14th and 16th centuries [xxii].

At the end of the 1400s a more centralised state emerged in the northern part of Cameroon around the Mandara mountains [xxiii]. This state was sometimes known as the Mandara Kingdom and sometimes as the Wandala [xxiv]. The Kingdom entered into conflict with the Dulo (or Duolo) tribe in the late 16th century [xxv] and established their capital in the city called Dulo following the successful conquest [xxvi]. In the decades that followed, the Dulo people attempted to regain power in the Mandara Kingdom and enlisted the Bornu Kingdom to help them [xxvii]. After a protracted conflict the Bornu Kingdom made one of their allies, Aldawa Nanda, King over the Mandara Kingdom in 1614 [xxviii]. However, after defeating the Bornu Kingdom in a war in around 1781, the Mandara Kingdom received tributes from a large number of neighbouring villages and became a regional power [xxix].

The Mandara and Bornu Kingdoms in northern Cameroon around 1850. Image source

The Mandara and Bornu Kingdoms in northern Cameroon around 1850. Image source

The Mandara Kingdom would begin its decline when a group of Fulani people invaded the area in a Jihad [xxx] (or holy war). The Kingdom continued to exist for another 100 years, but was continuously weakened by Fulani raiders and wars with the neighbouring Bornu Kingdom [xxxi].

The relationship between the Fulani people and the Mandara Kingdom was, however, more complicated than many historians suggest, as Mandara Kings would sometimes invite Fulani warriors to protect them from internal threats or enlist their support against local faction vying for power [xxxii]. There was therefore a large Fulani influence in the Mandara Kingdom long before the final Fulani conquest in 1893 [xxxiii].

With the German conquest of Cameroon in the early 1900s, most of the local kingdoms had lost their independence, although many of the institutions, customs and elites of the kingdoms continued to exert influence both during colonial occupation and afterwards [xxxiv].

Cameroon under colonial occupation

Present day Cameroon was at different times occupied by, and divided between, three different colonial powers; Germany, Britain and France. With the raising of the German flag in Bimba on August 17, 1884, the area known then as “German Kamerun” officially became part of the German Empire [xxxv]. Ownership of Cameroon was contested between the German and British Empires, and was eventually awarded to Germany after the Berlin Conference in 1884 without the people of Cameroon having any say in the matter. [xxxvi]. While British traders and missionaries had a greater influence in the region, Germany was able to seize Cameroon by securing trade links in the area [xxxvii].

In the early years of the German occupation, rubber was discovered in the east part of the country where the Maka people lived. After a German merchant was killed in the area, German newspapers published a report stating that he had been eaten by cannibals [xxxviii]. These reports were easily accepted in Germany and spread quickly due to a great fascination with crimes involving cannibalism [xxxix].The German government capitalised on the domestic uproar caused by this news, using the opportunity and the public support to send an expedition to conquer the Maka people [xl]. Fictional or sensationalist accounts of African brutality were often used by European colonial empires as a means of inciting the European population into supporting military actions in Africa. This reinforced the insidious and often misunderstood idea in Europe that European conquest of Africa was about bringing civilisation to ‘primitive’ Africans, despite simply being a means for European empires to expand territory, access Africa’s natural resources and exploit a cheap labour force.

The German occupation of Kamerun saw the establishment of a multitude of different plantations, but particularly those producing palm oil and coffee [xli]. These plantations were created on the lush and nutrient-rich soil located on the slopes of Mount Cameroon. Plantations required the recruitment of a large labour force to work the land, and the initial conquest of land displaced much of the coastal population of the area who were forced inland. In turn, the German administration turned to the densely populated inland areas to recruit a work force for the plantations [xlii]. Forced labour was a common practice for the colonial powers who made quite the profit out of the colonies they occupied. However, the oppressive labour practices of forcing the inland population into working on plantations led to social upheavals and riots [xliii] and in 1914 an attempt by Germany to take over land in the Bell quarter of the city of Douala met with such resistance from the traditional Duala leadership that the Germans deposed and executed the sitting ruler, Rudolph Duala Manga Bell [xliv].

In 1922, after the First World War (1914 – 1918), German Kamerun was divided between the French Republic and the British Empire under a League of Nations mandate [xlv]. The British divided the narrow strip of land they occupied into Southern and Northern Cameroon [xlvi]. However, the division between Northern and Southern Cameroon was purely in name, as the area was administered as a single entity under British rule [xlvii]. The reason for the division had much to do with this part of Cameroon holding a League of Nations mandate in 1919 [xlviii]. The French part of Cameroon became known as “Cameroun” during the French colonial occupation.

During the colonial period much of the Cameroonian local leadership held contested roles [xlix]. Some were seen as heroes, such as Rudolph Duala Manga Bell and his successor Alexander Ndoumbe Douala Manga Bell< [l]. Yet they were also paradoxically dependant on, and complicit in, the colonial occupation. While Alexander Bell was revered as a national hero and elected to represent Cameroon in the French National Assembly, he was seen by the intellectual elite as subservient to his French masters [li]. Another Duala chief, Betote Akwa, was arrested by the French authorities for his resistance [lii], yet to attain his freedom Akwa was required to accept a compromised political position of partial cooperation with the colonial powers [liii]. The traditional leaders were particularly compromised in questions of land acquisition by France [liv].

Certain political parties were, to a larger degree, involved in anti-colonial activities; in French-occupied Cameroun, the Union of the Peoples of Cameroon (UPC) was founded on April 10 1948 [lv]. The anti-colonial party was ideologically left-wing and several of the party's founders were trade unionists [lvi]. After a failed uprising in 1955, the party began an armed struggle against the colonial state the following year, which continued beyond independence from France [lvii]. Many top leaders of the party were killed in exile by the French authorities< [lviii]. Other political parties, under the leadership of André Mbida and Ahmadou Ahidjo continued the drive towards independence while the UPC was pushed into exile or underground [lix]

On 23 December 1956 French Cameroun held a national election, and a year later the Cameroon parliament, known as the Assemblée Legislative Cameroun, declared that French Cameroun was a state in its own right [lx] thus paving the way for Cameroonian independence. Rubem Um Nyobe, leader of UPC, requested that the new parliament legalise the party [lxi]. The Cameroonian parliament refused to grant his request causing further civil unrest and violence. Nyobe was assassinated by French security forces before Cameroon gained independence[lxii]. In 1958 the Cameroonian parliament requested that the French government transfer all power over internal affairs to the Cameroonian people [lxiii].

After independence

Cameroun gained its independence from France after a series of negotiations on 1 January 1960 [lxiv]. The British parts of Cameroon gained independence on 1 October 1960, together with Nigeria [lxv]. The British Cameroons had for administrative reasons been run as part of Nigeria under British rule [lxvi]. After independence, the North and South British Cameroons were independent countries until they had a vote for whether they would be part of Cameroon or Nigeria. In February 1961 the previously British-controlled Southern Cameroon and the French controlled Republic of Cameroun joined and became a bilingual state, which became known as the Federal Republic of Cameroon [lxvii]. Northern Cameroon voted to join the Federation of Nigeria [lxviii].

Ahmadou Ahidjo was elected the first president of the Federal Republic of Cameroon and his party, the Cameroon National Union (CNU), won a majority in parliament [lxix]. The newly formed Republic of Cameroon was plagued by civil strife in its early years, as elements of the outlawed and Marxist-aligned UPC continued their fight for radical reform after independence [lxx]. Ahmadou Ahidjo and his supporters brutally won the civil war, which was fought over an extended period of time [lxxi]. Some argue that the war with UPC gave President Ahidjo the necessary justification to centralise power into the presidency, and to suppress any opposition [lxxii].

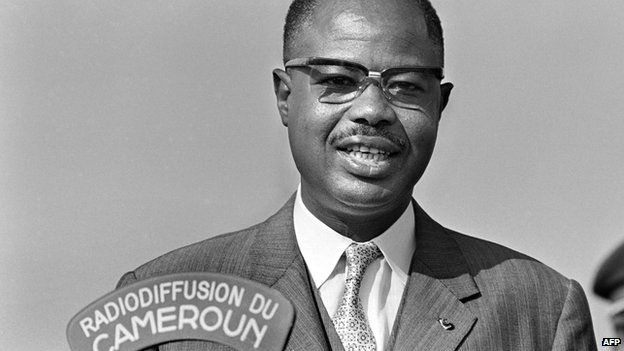

Ahmadou Ahidjo, first president of the Republic of Cameroon Image source

Ahmadou Ahidjo, first president of the Republic of Cameroon Image source

Ahidjo ruled until 1982, after which he stepped down and relinquished power to his successor Paul Biya [lxxiii]. Two years later, in 1984, soldiers from the northern part of Cameroon attempted to seize power in a palace coup [lxxiv]. Suspecting a potential coup, President Biya had acted pre-emptively by transferring all guards out of the palace [lxxv]. This had caused the leaders of the coup to act to early, although the coup attempt was crushed and a large number of people were killed in the heavy fighting [lxxvi].

While during Ahidjo's rule the country had experienced a large degree of stability, steady economic growth [lxxvii] and opportunities for upwards social mobility for ordinary Cameroonians, Biya’s presidency saw the Cameroonian economy spiral downwards. Biya implemented a series of structural economic reforms as a condition for continued aid from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank [lxxviii]. The reforms included cuts in government spending and large scale privatisation of public services [lxxix]. Schools, universities and hospitals had their funding cut, and public wages decreased while Cameroon – as part of the aid conditionality – was forced to restructure its political system to include multiple political parties and democratisation [lxxx].. The reforms would negatively impact the quality of life of ordinary Cameroonians [lxxxi].

The 1990's was marked by internal strife and a secessionist movement in the Southern part of the country. A new party, the Social Democratic Front (SDF), emerged on the political scene and held a rally with an estimated 20 000 participants [lxxxii]. Six people were shot by the police in the aftermath of the rally and their deaths would spark further anti-government sentiments [lxxxiii]. 1991 was an equally turbulent year, yet after much dispute and despite being a multi-party democracy, President Biya maintained his incumbency [lxxxiv].

In 2008 the country experienced large-scale, violent protests against high fuel prices and a high cost of living. Cameroonians had for years experienced a decline in standards of living, and between 2004 and 2008 the global financial crisis and an astronomical rise in global food prices caused further suffering [lxxxv]. Some sources claim that as many as 139 people were killed in the violence, and that most of them were young protesters [lxxxvi].

Most recently the northern borders and towns of the country has been plagued by a series of attacks by the Nigerian militant group calling themselves Boko Haram. Cameroonian forces have been making slow gains in driving back the group, which has inflicted devastating casualties on the population and has caused massive damage to infrastructure [lxxxvii].

Endnotes

[i] Fowler, Ian and David Zeitlyn. 1996. African Crossroads: Intersections Between History and Anthropology in Cameroon. Oxford: Berghahn Books. Page xviii. ↵

[ii] Ibid. ↵

[iii] Ardener, Edwin. 1962. “The Political History of Cameroon” in The World Today Vol. 18, No. 8 (Aug., 1962). Page 341. ↵

[iv] Ibid. Page 342. ↵

[v] Ibid. Page 342. ↵

[vi] Milton H. Krieger and Joseph Takougang. 2000. African State and Society in the 1990s: Cameroon's Political Crossroads. Westview Press. Page 606. ↵

[vii] Ibid. ↵

[viii] Ibid. ↵

[ix] Ardener, Edwin. 1962. “The Political History of Cameroon” in The World Today Vol. 18, No. 8 (Aug., 1962). Page 341. ↵

[x] DeLancey, Mark W., Mbuh, Rebecca N. and DeLancey, Mark Dike. 2010. Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Cameroon (3rd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. Page 3. ↵

[xi] Ibid. Page 3. ↵

[xii] Warnier, Jean-Pierre. 2012. Cameroonian Grassfields Civilization. Langaa Research & Publishing CIG, Mankon, Bamenda. Page 10. ↵

[xiii] Fowler, Ian and David Zeitlyn. 1996. African Crossroads: Intersections Between History and Anthropology in Cameroon. Oxford: Berghahn Books. Page 3. ↵

[xiv] Warnier, Jean-Pierre. 2012. Cameroonian Grassfields Civilization. Langaa Research & Publishing CIG, Mankon, Bamenda. Page 51. ↵

[xv] Ibid. ↵

[xvi] Ibid. Page 21. ↵

[xvii] Ibid. ↵

[xviii] Ibid. ↵

[xix] DeLancey, Mark W., Mbuh, Rebecca N. and DeLancey, Mark Dike. 2010. Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Cameroon (3rd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. Page 3. ↵

[xx] Warnier, Jean-Pierre. 2012. Cameroonian Grassfields Civilization. Langaa Research & Publishing CIG, Mankon, Bamenda. Page 15. ↵

[xxi] Ibid. ↵

[xxii] Ibid. ↵

[xxiii] Barkindo, Bawuro Mubi. 1989. The Sultanate of Mandara to 1902. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag. ↵

[xxiv] Mshelia, Ayuba Y. 2014. The Story of the Origins of the Bura/Pabir People of Northeast Nigeria: Language, Migrations, the Myth of Yamata-ra-wala, Social Organisation and Culture. Bloomington: Authorhouse LLC. Page 59. ↵

[xxv] Ibid. ↵

[xxvi] Ibid. ↵

[xxvii] Ibid. ↵

[xxviii] Ibid. ↵

[xxix] Ibid. ↵

[xxx] Ibid. Page 60. ↵

[xxxi] Ibid. ↵

[xxxxii] Fowler, Ian and David Zeitlyn. 1996. African Crossroads: Intersections Between History and Anthropology in Cameroon. Oxford: Berghahn Books. Page 3. ↵

[xxxiii] DeLancey, Mark W., Mbuh, Rebecca N. and DeLancey, Mark Dike. 2010. Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Cameroon (3rd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. Page 234. ↵

[xxxiv] Ibid. Page 4. ↵

[xxxv] Diduk, Susan. 1993. “European Alcohol, History, and the State in Cameroon” in African Studies Review / Volume 36 / Issue 01 / April 1993, pp 1-42. Page 1. ↵

[xxxvi] Ibid. ↵

[xxxvii] Ardener, Edwin. 1962. “The Political History of Cameroon” in The World Today Vol. 18, No. 8 (Aug., 1962). Page 343. ↵

[xxxviii] Geschiere, Peter. 2000 [1997] The Modernity of Witchcraft: Politics and the Occult in Postcolonial Africa. University of Virginia Press. Page 29. ↵

[xxxix] Ibid. ↵

[xl] Ibid. ↵

[xli] Fowler, Ian and David Zeitlyn. 1996. African Crossroads: Intersections Between History and Anthropology in Cameroon. Oxford: Berghahn Books. Page 4. ↵

[xlii] Ardener, Edwin. 1962. “The Political History of Cameroon” in The World Today Vol. 18, No. 8 (Aug., 1962). Page 343. ↵

[xliii] Ibid. ↵

[xliv] Fowler, Ian and David Zeitlyn. 1996. African Crossroads: Intersections Between History and Anthropology in Cameroon. Oxford: Berghahn Books. Page 63. ↵

[xlv] Ardener, Edwin. 1962. “The Political History of Cameroon” in The World Today Vol. 18, No. 8 (Aug., 1962). Page 341. ↵

[xlvi] Ibid. ↵

[xlvii] Ibid. ↵

[xlviii] Ibid. ↵

[xlix] Austen, Ralph. 1992. “Tradition, Invention and History: The Case of the Ngondo, (Cameroon) (Tradition, invention et histoire: le cas du Ngondo (Cameroun))” in Cahiers d'Études Africaines Vol. 32, Cahier 126 (1992), pp. 285-309. Page 294. ↵

[l] Fowler, Ian and David Zeitlyn. 1996. African Crossroads: Intersections Between History and Anthropology in Cameroon. Oxford: Berghahn Books. Page 139. ↵

[li] Austen, Ralph. 1992. “Tradition, Invention and History: The Case of the Ngondo, (Cameroon) (Tradition, invention et histoire: le cas du Ngondo (Cameroun))” in Cahiers d'Études Africaines Vol. 32, Cahier 126 (1992), pp. 285-309. Page 294. ↵

[lii] Ibid. ↵

[liii] Ibid. ↵

[liv] Ibid. Page 300. ↵

[lv] DeLancey, Mark W., Mbuh, Rebecca N. and DeLancey, Mark Dike. 2010. Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Cameroon (3rd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. Page 44. ↵

[lvi] Ibid. ↵

[lvii] Ardener, Edwin. 1962. “The Political History of Cameroon” in The World Today Vol. 18, No. 8 (Aug., 1962). Page 347. ↵

[lviii] DeLancey, Mark W., Mbuh, Rebecca N. and DeLancey, Mark Dike. 2010. Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Cameroon (3rd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. Page 251. ↵

[lix] Ardener, Edwin. 1962. “The Political History of Cameroon” in The World Today Vol. 18, No. 8 (Aug., 1962). Page 347. ↵

[lx] DeLancey, Mark W., Mbuh, Rebecca N. and DeLancey, Mark Dike. 2010. Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Cameroon (3rd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. Page 50. ↵

[lxi] Ardener, Edwin. 1962. “The Political History of Cameroon” in The World Today Vol. 18, No. 8 (Aug., 1962). Page 347. ↵

[lxii] Ibid. ↵

[lxiii] I DeLancey, Mark W., Mbuh, Rebecca N. and DeLancey, Mark Dike. 2010. Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Cameroon (3rd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. Page 182. ↵

[lxiv] Ibid. Page 325. ↵

[lxv] Ardener, Edwin. 1962. “The Political History of Cameroon” in The World Today Vol. 18, No. 8 (Aug., 1962). Page 342. ↵

[lxvi] Ibid. ↵

[lxvii] Ibid. ↵

[lxviii] Ibid. ↵

[lxix] Milton H. Krieger and Joseph Takougang. 2000. African State and Society in the 1990s: Cameroon's Political Crossroads. Westview Press. Page 606. ↵

[lxx] DeLancey, Mark W., Mbuh, Rebecca N. and DeLancey, Mark Dike. 2010. Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Cameroon (3rd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. Page 7. ↵

[lxxi] Ibid. ↵

[lxxii] Ibid. ↵

[lxxiii] Milton H. Krieger and Joseph Takougang. 2000. African State and Society in the 1990s: Cameroon's Political Crossroads. Westview Press. Page 606. ↵

[lxxiv] Ibid. ↵

[lxxv] Ibid. ↵

[lxxvi] DeLancey, Mark W., Mbuh, Rebecca N. and DeLancey, Mark Dike. 2010. Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Cameroon (3rd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. Page 8. ↵

[lxxvii] Milton H. Krieger and Joseph Takougang. 2000. African State and Society in the 1990s: Cameroon's Political Crossroads. Westview Press. Page 606. ↵

[lxxviii] Ibid. ↵

[lxxix] Ibid.. ↵

[lxxx] Ibid. ↵

[lxxxi] Ibid. ↵

[lxxxii] Ibid. Page 609. ↵

[lxxxiii] Ibid. ↵

[lxxxiv] Ibid. ↵

[lxxxv] Amin, Julius A. 2012. “Understanding the Protest of February 2008 in Cameroon” in Africa Today Volume 58, Number 4, Summer 2012. Page 21. ↵

[lxxxvi] Ibid. Page 35. ↵

[lxxxvii] Cameroon Profile: Timeline. 2015. Online. Available: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-13148483 ↵