Chad is the fifth largest country in Africa[i]. Chad is estimated to be one of the areas for where the human species originated[ii]. The area which is now known as Chad has a long and complicated history. It was a central part of some of Africa's greatest Empires such as the Kanem-Borno, which originated in the south western part of Chad[iii]. The lands both north and south of Lake Chad were particularly lush and fertile and were home to several ancient Kingdoms between 1 000 and 500 BCE[iv]. In the early 20th century Chad became a French colony and later gained its independence in 1960. It was the French colonial period which saw the formation of Chad as a nation state[v]. Post-colonial Chad was marred by both a small scale war with Libya and a protracted internal conflict from 1966 to the 1990s[vi]. After clashes around the border with Darfur, in Sudan, a limited conflict between the two countries followed in 2005[vii]. Later this limited engagement would expand to a five year long internal conflict which ended in January 2010[viii].

From the cradle of humankind to African Empires

The area now known as Chad was home to an estimated 200 ethnic groups and about 110 languages[ix]. This diversity shaped the history of Chad. Some argue that Chad is one of several potential sites for the cradle of humankind in Africa[x]. The discovery of a 6 to 7 million year old hominid like skull, now known as the Sahelanthropus tchadensis skull substantiates this claim[xi].

More recent human settlement in the area is estimated to have happened in the last 10 000 years[xii]. It is assumed that 7 000 BCE the region was not as arid as it is today; this is also the period in which we see definite proof of permanent human settlement[xiii]. People lived and farmed around the shores of lakes in the north central basin of the Sahara. Pastoralism became a common mode of production at around 5000 BCE[xiv]. After 3000 BCE the first trans-Saharan trade route was established through Chad[xv]. It is from around this time, that we can see traces of one of the first prominent distinctive groups of people in Chad, the Sao nation[xvi]. The Sao people are famous for their fortified walled cities[xvii].

Between 700 and 900 CE the Kanembu emerged as a regional power in Chad, and displaced the Sao people from power[xviii]. The Kanembu people brought with them knowledge of iron works and improved agriculture[xix]. Historians argue that these technological advances would lead to the formation of a more centralised Kingdom; which is sometimes referred to as the Kanembu Kingdom[xx]. Later Islamic scholars would describe the Kingdom first as the Duguwa Kingdom, and then, after a rebellion by court officials, as the Sayfuwa Kingdom, so named after the two different ruling dynasties[xxi]. Some scholars trace the first Duguwa Kings all the way back to 700 CE[xxii]. Yet both the names refers to the Kanem Kingdom, but ruled by different dynasties.

Around 1 000 CE Berber's, and traders displaced from West Africa by conflict brought Islam to the Kanembu[xxiii]. The religion was quickly adopted by various court officials and nobles. The foreign Berbers and the local court officials saw Islam as a greater principle to organise the various anti-Duguwa factions around, and overthrew the Duguwa dynasty[xxiv]. Officially the Duguwa kings lost their power to the Sayfuwa in 1068, but it is estimated that they had lost much of their real power some years prior[xxv]. Less than 200 years later, because of internal conflict surrounding religious practice, the Sayfuwa dynasty was displaced by the Bulala people from Kanembu, and moved west to found the state of Borno[xxvi]. It is estimated that the Sayfuwa was firmly established in Borno by the mid 1300s[xxvii]. With the same ruling dynasty and similar traditions there was a clear continuation between the Kamen and Borno Kingdoms[xxviii].

By the mid 1400s the Sayfuwa kings of the Borno state founded the new capital city of Gazargamo[xxix]. Some years after the founding of the new capital the Borno state attacked and conquered their old capital in Kamen from the Bulala people[xxx]. During their stay in Borno the Sayfuwa kings had adopted many popular customs from the Sao people who had resided there since the 900s[xxxi]. With the unification of the two states of Borno and Kamen in the mid 1500s, and the inclusion of several different peoples (Bulala, Sao, Berber's, Kanembu, and more), the Kamen-Borno Empire was born[xxxii]. The Tubu people who lived in the northern part of the Kanem Kingdom became independent as the Kanem-Borno Empire did not manage to exert authority over them, which the previous Kanem Kingdom had held[xxxiii]. The Kanem-Borno Empire reached its height under Mai (local word for King) Idris Alooma (1580-1619)[xxxiv]. At this point the Empire was directly ruling over both the Kanem and Borno Kingdoms and receiving tribute from the far away Ouaddai and Darfur Kingdoms[xxxv].

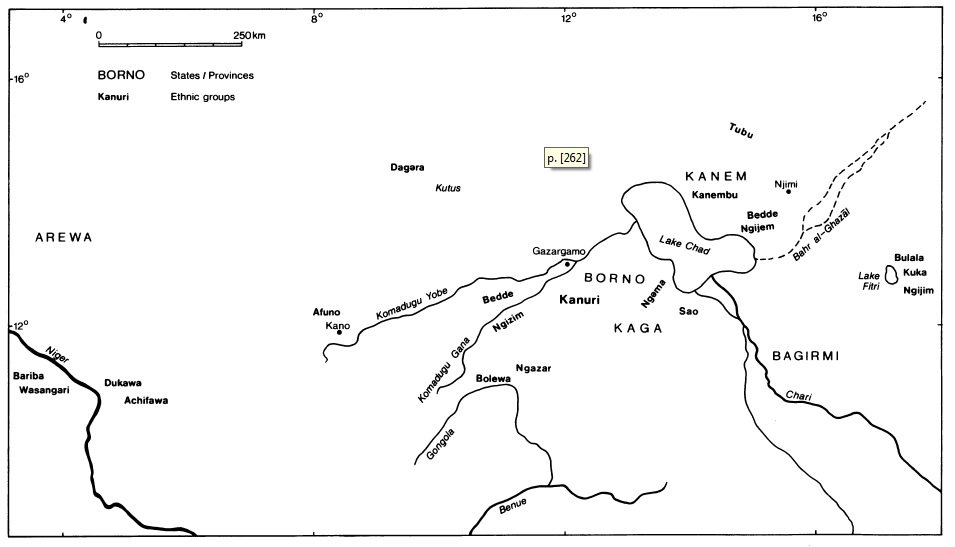

Image 1: Caption: The peoples living around lake Chad at around 1000 CE. Source: Lange, Dierk. 1993. “Ethnogenesis from within the Chadic State. Some Thoughts on the History of Kanem-Borno” in Paideuma: Mitteilungen zur Kulturkunde. Bd. 39 (1993), pp. 261-277.

The peoples living around lake Chad at around 1000 CE. Image source

The peoples living around lake Chad at around 1000 CE. Image source

The 1400s – 1800s was an era where several Empires would conquer and rule various parts of the area which now constitutes modern day Chad[xxxvi]. Most notable of these Empires were the Kamen-Bornu, Baguirmi, and Ouaddai[xxxvii]. Ouaddai (sometimes written as Wadai) was to the east of Kamen-Borno, and Baguirmi was to the north-west. All three empires converted to Islam at one point or another. The Ouaddai Kingdom was founded in the late 1500s by the Arab-speaking Tunjur people [xxxviii]. The Ouaddai Kingdom reached its height when it conquered the Bagurimi Kingdom somewhere between 1611 and 1635 CE[xxxix]. The Bagurimi Kingdom was also established in the 1500s, but soon after its founding it went into a period of decline, and the capital city of Massenya was burned several times over the next two centuries[xl]. The Kingdom would recover however, and reach new heights of power in the 1800s[xli].

Slavery was also a common practice in the three major states which dominated pre-colonial Chad[xlii]. By the mid 1700s the area where the Baguirmi Empire was had become one of the most important sources of slaves for the trans-Saharan trade[xliii]. A large part of these slaves would be sent across the Atlantic as part of the trans-Atlantic slave trade[xliv]. The Baguirmi captured slaves through conquest, but after losing several wars to the Kamen-Borno and Ouaddai Empires they were themselves subjected to slavery[xlv].

The southern part of Chad was largely populated by a series of less centralised political and social groups[xlvi]. Groups of elders or a village council would make decisions, and who made up these councils would often change. While in the north people were organised in larger more centralised entities with a hierarchical power structure, the south were looser knit political structures mainly engaged in agricultural activities[xlvii]. While the north was religiously unified under Islam, the south practised a variety of religions and rituals[xlviii]. The northern Kingdoms, especially the Bagurimi Kingdom, would often raid and pillage the southern part to capture slaves[xlix]. This is a history which still creates tensions between the north and the south of Chad today.

Rabah Zubair Fadlallah and the end of the Northern Kingdoms

Warriors of Rabah Zubair Fadlallah. Image source

Warriors of Rabah Zubair Fadlallah. Image source

Rabah Zubair Fadlallah (1840 -1900 CE) was born a slave, but gained his freedom (and fame) when he served in the army of Zubair Rahama Mansur al-Abbasi in south-east Ouaddai[l]. Rabah later became a warlord and a a slave trader himself, and ruler of most of northern Chad[li]. He would go on to conquer Ouaddai in the 1880s, burn Massenya and conquer Baguirmi in 1893, and had taken complete control of Borno by 1894[lii]. After this he took the title Emir of the faithful, and established the capital city of Dikwa, south of Lake Chad[liii].

During the period between 1880 and 1900 the Rabah Fadlallah took control of most of the northern part of the area now known as Chad. They would in turn enlist much of the local tribes’ sons into their forces. Particularly noble sons were taken into the Rabih army as hostages to secure the loyalty of local chiefs.

It was at this time, during the conquest of Rabah, that the French began to send expeditionary forces to bring the area into its colonial Empire[liv]. Rabah would often harass these expeditionary forces, and sometimes came into direct combat with them. In 1891 he fought the expeditionary force of French Lieutenant Paul Crampel (Crampel was killed two years later by Sultan al Sanussi of Dar Kuti)[lv]. In 1899 Rabah won a battle against the French and killed Lieutenant Bretonnet and most of his men[lvi]. This defeat made the French increase their efforts into conquering Chad, and sent out three columns to converge on Lake Chad[lvii]. Rabah set up his defence outside the town of Kousséri, and was defeated by the French in the battle which ensued. The story goes on and states that the French decapitated Rabah and dispalyed his head for all to see[lviii].

Rabah Fadlallah is seen as an African hero by many because of his staunch opposition to the French conquest. Some also seem him as a pan-Africanist, as he was in a process of uniting the various Kingdoms and political entities which ruled at the time[lix].

Colonial occupation

The colonial conquest of Chad by the French Empire was a long and arduous endeavour. As mentioned above there was great fighting between the French and Rabah, which would only come to an end in 1900. In 1905 after much loss of lives the Kanem were subdued, and on June 13, 1909 the Ouaddai lost their capital city of Abeche[lx]. Several smaller political entities and Kingdoms were conquered during the next ten years, and lastly the Tubu people surrendered in 1920[lxi]. The French set up their colonial administration in the city of N'djamena[lxii].

The French initially placed control of the region under a governor-general in Brazzaville (Congo), but in 1910 Chad was joined to the larger federation of Afrique Équatoriale Française (AEF, French Equatorial Africa)[lxiii]. Chad was one of the most neglected of the French colonies. Almost no investment was made in infrastructure or economic development during the French occupation. Only after the conquest of the Tubu in 1920 did Chad get a civilian government[lxiv]. On November 11, 1929, Tibesti changed hands from the colonial administration of Niger to that of Chad[lxv].

The forced recruitment of local recruitment of soldiers was a major issue in the Chad colony, and there were several incidents were towns physically fought colonial recruiters[lxvi]. One such incident ended in one recruiter being held hostage, while his guard was castrated[lxvii]. Another central form of exploitation in the Chad Colony was that of forced labour. There were three types of forced labour. The Chad colony had three types of obligations for providing forced labour. The first was that any administrator could ask any African, at any time, to work for private companies or for the government. Secondly, government projects deemed as “an emergency” could call upon Africans to work without compensation. Thirdly the colonial authorities could extract work from prisoners[lxviii].

The lack of French civil administrators willing to work in Chad, made the colonial authorities greatly dependant on local leaders for the keeping order in the colony[lxix]. So these orders for forced labour were in the final instance ordered and executed by local leaders, often referred to as “canton chiefs”[lxx]. The recruiters would use tactics such as theft of food and livestock, kidnapping hostages, and the burning of houses and crops, to coerce people who refused to join the forced labour[lxxi]. The largest forced labour project was the railway from Point-Noire to Brazzaville. 120 000 Africans and 600 Chinese workers were coerced into forced labour to complete the project[lxxii]. An estimated 10 000 workers would die before the railway was finished[lxxiii].

The Chad Colony was a brutal place to live for the local people. There was the obviously exploitative forced labour system, and on top of that, as a general rule, any European could order any African to become a porter at any time[lxxiv]. As if this was not enough famines were commonplace in the colony, and the colonial administration would constantly exacerbate the effects of the famines even as they were “attempting” to avert them[lxxv]. An estimated 30 000 people died from hunger between 1913 and 1918 alone[lxxvi].

There was also a tax system known as the “head tax” system. Parts of the tax had to be paid in currency which forced Chadians into becoming workers in the colonial economy and violence and coercion was often used when the colonial administration collected the tax[lxxvii]. Chadians made many attempts at resisting tax collection, and the French authorities would reply with severe and violent retribution. The most violent incident in relation to tax collection was in Bouna in the south of Chad. In 1928 the local chief who was in charge of collecting taxes in the area decided to charge double tax, and the Bouna people refused to pay[lxxviii]. The French authorities then responded by sending armed forces to “stop the incidents of tax evasion and revolt”[lxxix]. The French troops proceeded to kill an estimated 5 000 adults, slaughtering the domestic animals, and burning most of the canton[lxxx]. It is said that only women and children were left alive[lxxxi].

In 1939 Chad contributed greatly to the French war effort in World War II[lxxxii]. It was for instance one of the first regions to declare itself as part of “Free France” after the French government surrendered to Germany in 1940[lxxxiii].

The end of World War II would also mark the end of some of the harshest colonial policies. Forced labour was abolished and political parties were legalised in 1946[lxxxiv]. Although there would be two separate voting systems and a lack of universal suffrage until 1956[lxxxv]. Two political parties would dominate the struggle for independence from France, the Chadian Progressive Party (PPT) and Chadian Democratic Union (UDT)[lxxxvi]. The two parties came to represent the regional divisions which existed in Chad as a French colony, UDT catered to the Muslim population, while PPT had its support base in the southern part of the country[lxxxvii]. While UDT and PPT were the two largest parties, the period between 1946 and 1959 was marked by a fight for power between a variety of different parties in Chad, all representing various religious, cultural and regional interests[lxxxviii]. In many ways the struggle between various parties at this time would be a foreshadowing of the various conflicts which would dominate Chad after independence.

The PPT was the strongest party at the end of the colonial occupation, and would become the governing party after independence was declared. On the March 31, 1959, Chad held national elections and PPT won an overwhelming victory over the other parties[lxxxix]. A little more than a year later, on August 11, 1960, Chad declared independence from France[xc].

After independence

Chad faced serious violence and trouble after independence. In 1966 the country saw the beginning of one Africa's longest civil wars. It lasted more than 24 years and ended only in the early 1990s[xci]. It was not long after independence that one could see the signs of trouble. Francois Tombalbaye was Chad's first president, and soon after independence he centralised all decision making into the presidency, turning parliament into nothing but a rubber stamp[xcii]. In 1962 Tombalbaye had eliminated any official opposition parties, purged all enemies from the state, and turned Chad into a one-party state[xciii].

Tombalbaye then proceeded to make sure that all newly appointed civil servants had a background from the Sara people in the south[xciv]. This created tensions between the northern and the southern parts of the country. The northern marginalisation from state and the civil service fanned up under old conflicts dating back to before the colonial period[xcv]. This tension was further stoked when the President, in 1965, ordered a new tax on cattle and personal income, which was followed by immediate violence against tax collectors in the northern provinces[xcvi]. Tubu people in the north rose up against the government and killed one Chadian soldier, which in turn caused the regime to retaliate[xcvii]. The Tubu rebels fled to Libya after the government retaliations. It was not long, unfortunately, before civil war erupted between the predominantly Muslim north and predominantly Christian/animist south. On June 22, 1966, a group of Muslim intellectuals and nationalists met in Sudan and together formed the Front de Libération Nationale (FROLINAT), with Ibrahim Abatcha as the general secretary[xcviii].

The reasons for Chad's lengthy civil war are much debated. The first explanation deals mostly with the issues after 1960, and as a result of the power grab by President Tombalbaye[xcix]. He alienated the Muslim population by centralising power into the presidency and the PPT (a party which never represented a broad section of the Chadian people)[c]. This grab for power was followed by severe rioting in 1963 by the Muslim population of Chad[ci]. President Tombalbaye then purged the National Assembly of any dissident voices and effectively eradicated the last veils of democracy in the country[cii]. Following these developments there were a series of coups and political instability. Tombalbaye’s rule becamye more brutal and in 1975 General Felix Malloum took power in a coup[ciii]. He was replaced by Goukouni Wedei after another coup in 1979[civ]. Power changed hands twice more by coup: to Hissène Habré in 1982, and then to Idriss Déby in 1990[cv].

Another explanation for Chad's turbulent history is the country being a French colonial construction which ignored historical separation between the Muslim north and the Christian south[cvi]. The colonial occupational state also ignored the north while it developed the south which created unresolved issues in the post-colonial era. The colonial system also left weak public institutions and state apparatuses with little legitimacy in the general population[cvii]. The truth is most likely that both political instability and historical conflicts constructed by colonialism were both to blame for the civil violence in Chad, and was in turn exacerbated by foreign interventions and interference[cviii][cix].

Chadian troops receiving instruction on the use of antitank weapons. Image source

Chadian troops receiving instruction on the use of antitank weapons. Image source

In 1965 the Chadian government imposed a new cattle tax, and a tax riot ensued in the Batha Prefecture. The government sent in soldiers and ordered the killing of 500 Mubu people[cx]. By 1966 a full blown Civil War had broken out in Chad. FROLINAT started a guerilla campaign against the government and they were only kept in check by the support of French troops[cxi]. In the early 1970s Tombalbaye was only holding on to power thanks to French military support disguised as technical advisers[cxii]. In April 1974, a then virtually unknown, Hissène Habré attacked attacked the city of Bardai and took several Europeans hostage[cxiii]. After a series of political mistakes Tombalbaye was assassinated by General Felix Malloum in April 1975[cxiv].

President Malloum started his reign by attempting to make peace in Chad, he freed 173 political prisoners and invited several northerners from the Tubu-Arab alliance to join his cabinet[cxv]. With the exception of Hissène Habré and Gukuni Wedei, most rebell groups temporarily stopped the fighting[cxvi]. The new Presidents first mistake, however, was to expel 1500 French troops after the French government had decided to negotiate with Hissène Habré for the release of two French hostages[cxvii]. In 1977 President Malloum ordered the execution of several military officers. Less than a year later, between March and April 1978, the rebels captured two towns: Ounianga-Kebir and Faya-Largeau[cxviii]. To appease the rebels Habré was appointed Prime minister on Augus 29 1978[cxix]. Some speculate that the leaders of Zaire (Democratic Republic of Congo), Central African Republic, France and Gabon persuaded Malloum to trust Habré[cxx].

The situation would quickly deteriorate for President Malloum after this. Prime minister Habré and President Malloum would clash as both tried to take power over the government, and on February 12, 1979, fighting broke out in the capital of N'Djamena, between their respective troops[cxxi]. French attempts at negotiating a peace treaty only hampered the President's efforts to defeat the opposition[cxxii]. By February 1979 Chad was divided in three between the government forces (FAT) in the southern region, FROLINAT in the north, and the alliance between Hissène Habré's National Armed Forces (FAN) and Gukuni Wedei's Peoples Armed Forces (FAP) in the central parts around the capital[cxxiii]. With the country heading for total collapse President Felix Malloum left the country for exile in Nigeria.

A unity government was established between the various rebel factions with Gukuni Wedei as President. Fighting soon broke out between the factions of Habré and Wedei, and in 1980 there was full out war between them[cxxiv]. Habré is supposed to have been spurred on by a $10 Million backing by the CIA as well as military backing by France[cxxv]. Both drew their support from the northern Tubu people, and the following war would be extremely bloody. Habré first captured the capital and then, in 1982, he marched south and with many civilian causalities he captured Sarh and Moundou, and effectively becoming president of the country[cxxvi]. In 1983 Wedei, supported by Libya, moved southwards, but was halted by Habré's troops which were backed by French forces[cxxvii]. This was the beginning of the northern rule over the whole of Chad, and by 1985 Gukuni Wedei seemed to have all but lost the war.

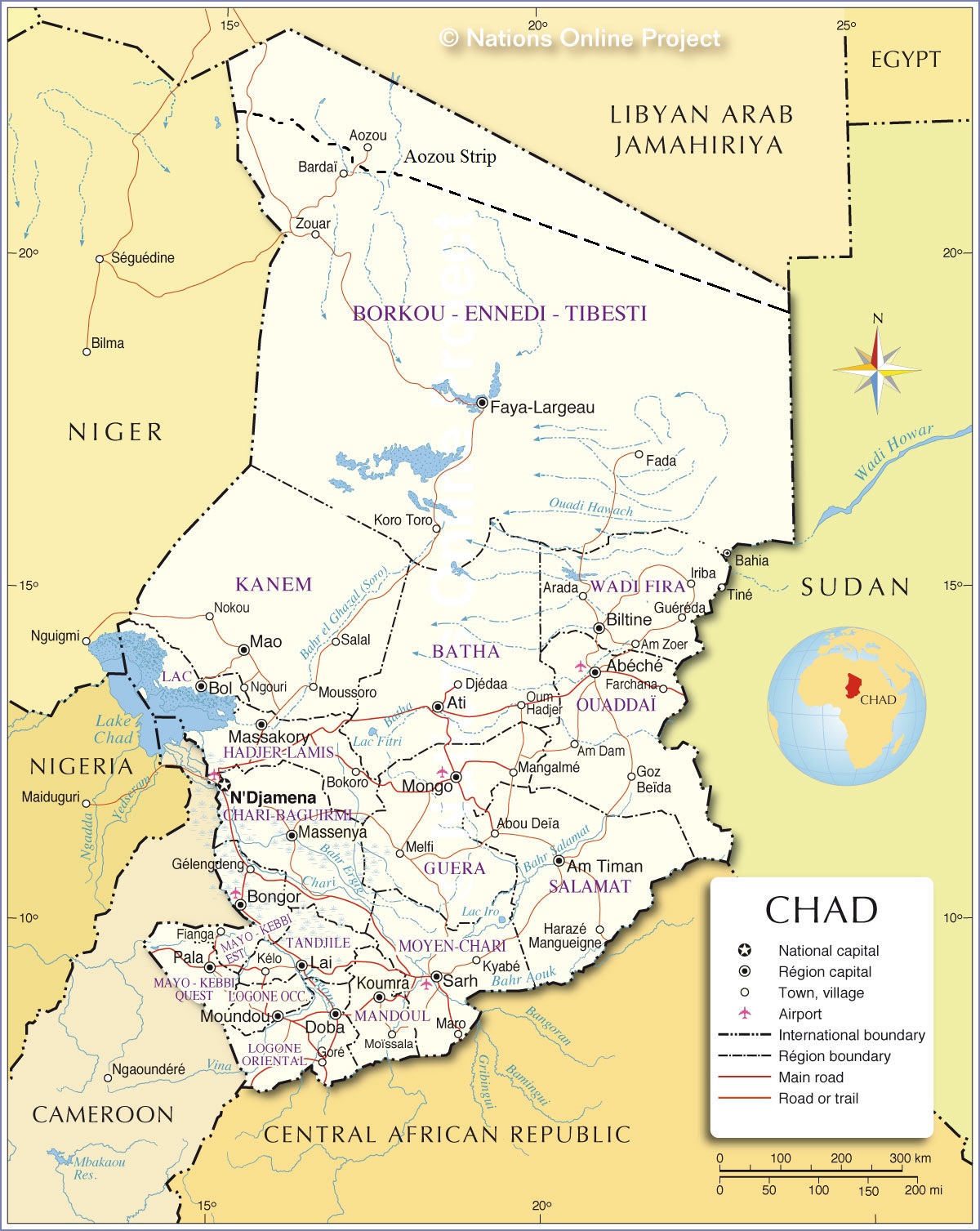

Contemporary map of Libya including the contested Aouzou Strip. Image source

Contemporary map of Libya including the contested Aouzou Strip. Image source

With increased support from Libya and with the French backing down, Wedei was able to continue the fighting as the Civil War would increasingly intensify in 1986[cxxviii]. Wedei might have been backed by the Libyans, but Habré was by far the better military strategist, and he was backed by two brilliant commanders: Chief Hassan Djamous and Idriss Déby[cxxix]. The regular Libyan forces were not motivated for the fight however, and Habré's guerilla tactics would take a huge toll on morale[cxxx]. By 1990 the Libyan military was only in control of the contested Aouzou Strip in the north. After about 23 years of internal conflict Habré can be credited with having united Chad again.

After Habré had united the country in 1989 several rebel groups still remained active in various ways. President Habré was also slow to move the country towards democratic reform[cxxxi]. Fearing that the might be imprisoned, a former ally of Habré, Idris Déby fled the capital city in 1989[cxxxii]. Déby rapidly gathered the various forces against the President. The national army deserted the regime, and the French military forces claimed neutrality, and Déby entered the capital unopposed as Habré fled to Cameroon[cxxxiii]. In 1990 Déby, at the head of a new rebel group, the Patriotic Salvation Movement, removed Habré and made himself president (in 2005 Habré was charged with crimes against humanity for the torture and killings of thousands of people)[cxxxiv]. In May 2016 Habré was convicted for crimes against humanity after having supposedly ordered the killing of as many as 40,000 people[cxxxv].

The first multi-party, democratic elections held since independence reaffirmed Déby in 1996[cxxxvi]. President Déby would face several rebellions during his time as president[cxxxvii]. Both in 2006 and 2008 the capital city was attacked by rebels[cxxxviii]. In 2003 Chad was drawn into the Sudanese civil war, and the country was again facing violent conflict[cxxxix]. From 2005 – 2010 various militias attacked villages and cities in eastern Chad[cxl]. In the aftermath of these attacks Sudan was accused of sponsoring the rebels in an effort to destabilise Chad[cxli]. In 2010 Chad and Sudan signed a peace agreement. President Déby was re-elected president in 1996, 2006, 2011 and 2016 (after a 2005 referendum allowed him to exceed the two term limit[cxlii].

President Hissène Habré. Image source

President Hissène Habré. Image source

President Idriss Déby Itno. Image source

President Idriss Déby Itno. Image source

Presidents of the Republic of Chad

11 Aug 1960 - 13 Apr 1975François N'Garta Tombalbaye

7 Jun 1982 - 1 Dec 1990 Hissène Habré

1 Dec 1990 - 2 Dec 1990 Jean Alingue Bawoyeu

2 Dec 1990 - presentIdriss Déby Itno

Heads of State

13 Apr 1975 - 15 Apr 1975 - Noël Milarew Odingar

15 Apr 1975 - 23 Mar 1979 - Félix Malloum N'Gakoutou

Chairman of the Provisional Council of State

23 March 1979 - 29 April 1979Goukouni Oueddei

Head of the Gouvernement d'Union Nationale de Transition (GUNT, National Union Transition Government)

29 Apr 1979 - 3 Sep 1979Lol Mohamed Shawa

3 Sep 1979 - 7 Jun 1982 Goukouni Oueddei

Sources:

Azevedo, M. J. 1998. The Roots of Violence: A History of War in Chad. Gordon and Breach Publishers, Amsterdam.

Azevedo, M. J., and Nnadozie, E. U. 1998. Chad: A Nation in Search of Its Future. Westwind Press, Oxford.

BBC News. 30 May 2016. “Hissene Habre: Chad's ex-ruler convicted of crimes against humanity” http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-36411466. (Accessed the 30.05.2016).

BBC News. 7 April 2016. “Chad profile – Timeline”. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-1316469. Accessed the 30.05.2016).

Collier, John L., ed. 1990. “Historical Setting” in Chad: A Country Study. Library of Congress Country Studies (2nd ed.), Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress

Decalo, Samuel. 1980. “The Roots of Centre-Periphery Strife” in African Affairs, Vol. 79, No. 317 (Oct., 1980), pp. 490-509. Page 491.

Gronenborn, Detlef. 1998. “Archaeological and Ethnohistorical Investigations Along the Southern Fringes of Lake Chad, 1993–1996” in African Archaeological Review December 1998, Volume 15,Issue4, pp 225-259.

Hancock, Stephanie. 2005. “Chad in 'state of war' with Sudan” in BBC News Friday, 23 December 2005. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/4556576.stm (Accessed the 10.05.2016).

Human Rights Watch. 2011. World Report 2011: Chad. Events of 2010. https://www.hrw.org/node/259443 (Accessed on the 10.05.2016)

Kuper, Rudolph and Kröpelin, Stefan. 2006. “Climate-controlled Holocene occupation in the Sahara: motor of Africa's evolution” in Science 313, 803 (2006); DOI: 10.1126/science.1130989. ,

La Rue, George Michael. 2003. “The Frontiers of Enslavement: Bagirmi and the Trans-Saharan Slave Routes” in Slavery on the Frontiers of Islam, Paul Lovejoy (eds.). Markus Wiener Publishers: Princeton NY.

Lange, Dierk. 1993. “Ethnogenesis from within the Chadic State. Some Thoughts on the History of Kanem-Borno” in Paideuma: Mitteilungen zur Kulturkunde. Bd. 39 (1993), pp. 261-277.

Stapelton, Timothy, J. A Military History of Africa, Volume 1. The Colonial Period: From the Scramble for Africa to the Algerian Independence War (ca. 1870-1963). Praeger Publishers, Santa Barbra, California.

Wood, Bernard. 2002. “Palaeoanthropology: Hominid revelations from Chad” in Nature 418, 133-135 (11 July 2002). doi:10.1038/418133.

End Notes

[i] Azevedo, M. J. 1998. The Roots of Violence: A History of War in Chad. Gordon and Breach Publishers, Amsterdam. Page 2. ↵

[ii] Wood, Bernard. 2002. “Palaeoanthropology: Hominid revelations from Chad” in Nature 418, 133-135 (11 July 2002) doi:10.1038/418133. ↵

[iii] Gronenborn, Detlef. 1998. “Archaeological and Ethnohistorical Investigations Along the Southern Fringes of Lake Chad, 1993–1996” in African Archaeological Review December 1998, Volume 15,Issue4, pp 225-259. Page 227. ↵

[iv] Ibid. ↵

[v] Azevedo, M. J. 1998. The Roots of Violence: A History of War in Chad. Gordon and Breach Publishers, Amsterdam. Page 2. ↵

[vi] Ibid. ↵

[vii] Hancock, Stephanie. 2005. “Chad in 'state of war' with Sudan” in BBC News Friday, 23 December 2005. ↵

[viii] Human Rights Watch. 2011. World Report 2011: Chad. Events of 2010. https://www.hrw.org/node/259443 ↵

[ix] Collier, John L., ed. 1990. “Historical Setting” in Chad: A Country Study. Library of Congress Country Studies (2nd ed.), Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. Page xiii. ↵

[x] Wood, Bernard. 2002. “Palaeoanthropology: Hominid revelations from Chad” in Nature 418, 133-135 (11 July 2002) | doi:10.1038/418133. ↵

[xi] Ibid. ↵

[xii] Kuper, Rudolph and Kröpelin, Stefan. 2006. “Climate-controlled Holocene occupation in the Sahara: motor of Africa's evolution” in Science 313, 803 (2006); DOI: 10.1126/science.1130989. Page 803. ↵

[xiii] Ibid. Page 805. ↵

[xiv] Ibid. ↵

[xv] Ibid. ↵

[xvi] Azevedo, M. J. 1998. The Roots of Violence: A History of War in Chad. Gordon and Breach Publishers, Amsterdam. Page 7. ↵

[xvii] Ibid. ↵

[xviii] Azevedo, M. J. 1998. The Roots of Violence: A History of War in Chad. Gordon and Breach Publishers, Amsterdam. Page 7. ↵

[xix] Ibid. ↵

[xx] Ibid. ↵

[xxi] Lange, Dierk. 1993. “Ethnogenesis from within the Chadic State. Some Thoughts on the History of Kanem-Borno” in Paideuma: Mitteilungen zur Kulturkunde. Bd. 39 (1993), pp. 261-277. Page 263. ↵

[xxii] Ibid. Page 264. ↵

[xxiii] Ibid. ↵

[xxiv] Ibid. Page 265. ↵

[xxv] Ibid. ↵

[xxvi] Ibid. Page 269. ↵

[xxvii] Ibid. Page 370. ↵

[xxviii] Ibid. ↵

[xxix] Ibid. Page 274. ↵

[xxx] Ibid. ↵

[xxxi] Ibid. Page 279. ↵

[xxxii] Ibid. Page 275. ↵

[xxxiii] Ibid. ↵

[xxxiv] Azevedo, M. J., and Nnadozie, E. U. 1998. Chad: A Nation in Search of Its Future. Westwind Press: Oxford. Page 14. ↵

[xxxv] Ibid. ↵

[xxxvi] Azevedo, M. J. 1998. The Roots of Violence: A History of War in Chad. Gordon and Breach Publishers, Amsterdam. Page 21. ↵

[xxxvii] Ibid. ↵

[xxxviii] Azevedo, M. J., and Nnadozie, E. U. 1998. Chad: A Nation in Search of Its Future. Westwind Press: Oxford. Page 14. ↵

[xxxix] Ibid., page 15. ↵

[xl] Ibid., page 16. ↵

[xli] Ibid. ↵

[xlii] Azevedo, M. J. 1998. The Roots of Violence: A History of War in Chad. Gordon and Breach Publishers, Amsterdam. Page 21. ↵

[xliii] La Rue, George Michael. 2003. “The Frontiers of Enslavement: Bagirmi and the Trans-Saharan Slave Routes” in Slavery on the Frontiers of Islam, Paul Lovejoy (eds.). Markus Wiener Publishers: Princeton NY. Page 31. ↵

[xliv] Ibid. Page 34. ↵

[xlv] Ibid. Page 36. ↵

[xlvi] Azevedo, M. J., and Nnadozie, E. U. 1998. Chad: A Nation in Search of Its Future. Westwind Press: Oxford. Page 17. ↵

[xlvii] Ibid. ↵

[xlviii] Ibid. ↵

[xlix] Ibid. ↵

[l] Ibid., Page 16. ↵

[li] Ibid., Page 18. ↵

[lii] Ibid. ↵

[liii] Ibid. ↵

[liv] Ibid. ↵

[lv] Ibid. ↵

[lvi] Stapelton, Timothy, J. A Military History of Africa, Volume 1. The Colonial Period: From the Scramble for Africa to the Algerian Independence War (ca. 1870-1963). Praeger Publishers, Santa Barbra, California. Page 26. ↵

[lvii] Ibid. ↵

[lviii] Ibid. ↵

[lix] Azevedo, M. J., and Nnadozie, E. U. 1998. Chad: A Nation in Search of Its Future. Westwind Press: Oxford. Page 18. ↵

[lx] Ibid. ↵

[lxi] Ibid. ↵

[lxii] Stapelton, Timothy, J. A Military History of Africa, Volume 1. The Colonial Period: From the Scramble for Africa to the Algerian Independence War (ca. 1870-1963). Praeger Publishers, Santa Barbra, California. Page 26. ↵

[lxiii] Azevedo, M. J., and Nnadozie, E. U. 1998. Chad: A Nation in Search of Its Future. Westwind Press: Oxford. Page 18. ↵

[lxiv] Ibid. ↵

[lxv] Ibid. ↵

[lxvi] Ibid. Page 19. ↵

[lxvii] Ibid. ↵

[lxviii] Ibid. Page 21. ↵

[lxix] Ibid. ↵

[lxx] Ibid. ↵

[lxxi] Ibid. ↵

[lxxii] Ibid. Page 23. ↵

[lxxiii] Ibid. ↵

[lxxiv] Ibid. Page 25. ↵

[lxxv] Ibid. Page 28. ↵

[lxxvi] Ibid. ↵

[lxxvii] Ibid. Page 25. ↵

[lxxviii] Ibid. Page 27. ↵

[lxxix] Ibid. ↵

[lxxx] Ibid. ↵

[lxxxi] Ibid. ↵

[lxxxii] Ibid. Page 20. ↵

[lxxxiii] Ibid. ↵

[lxxxiv] Ibid. Page 35. ↵

[lxxxv] Ibid. Page 36. ↵

[lxxxvi] Ibid. Page37. ↵

[lxxxvii] Ibid. Page 36 and 37. ↵

[lxxxviii] Ibid. Page 44. ↵

[lxxxix] Ibid. Page 40. ↵

[xc] Ibid. Page 45. ↵

[xci] Azevedo, M. J. 1998. The Roots of Violence: A History of War in Chad. Gordon and Breach Publishers, Amsterdam. Page 2. ↵

[xcii] Azevedo, M. J., and Nnadozie, E. U. 1998. Chad: A Nation in Search of Its Future. Westwind Press: Oxford. Page 45. ↵

[xciii] Ibid. Page 47. ↵

[xciv] Ibid. ↵

[xcv] Ibid. ↵

[xcvi] Ibid. Page 48. ↵

[xcvii] Ibid. ↵

[xcviii] Ibid. ↵

[xcix] Azevedo, M. J. 1998. The Roots of Violence: A History of War in Chad. Gordon and Breach Publishers, Amsterdam. Page 3. ↵

[c] Decalo, Samuel. 1980. “The Roots of Centre-Periphery Strife” in African Affairs, Vol. 79, No. 317 (Oct., 1980), pp. 490-509. Page 499. ↵

[ci] Ibid. ↵

[cii] Ibid. ↵

[ciii] Azevedo, M. J. 1998. The Roots of Violence: A History of War in Chad. Gordon and Breach Publishers, Amsterdam. Page 3. ↵

[civ] Ibid. ↵

[cv] Ibid. ↵

[cvi] Ibid. ↵

[cvii] Decalo, Samuel. 1980. “The Roots of Centre-Periphery Strife” in African Affairs, Vol. 79, No. 317 (Oct., 1980), pp. 490-509. Page 491. ↵

[cviii] Azevedo, M. J. 1998. The Roots of Violence: A History of War in Chad. Gordon and Breach Publishers, Amsterdam. Page 3. ↵

[cix] Decalo, Samuel. 1980. “The Roots of Centre-Periphery Strife” in African Affairs, Vol. 79, No. 317 (Oct., 1980), pp. 490-509. Page 491. ↵

[cx] Azevedo, M. J., and Nnadozie, E. U. 1998. Chad: A Nation in Search of Its Future. Westwind Press: Oxford. Page 48. ↵

[cxi] Ibid. ↵

[cxii] Decalo, Samuel. 1980. “The Roots of Centre-Periphery Strife” in African Affairs, Vol. 79, No. 317 (Oct., 1980), pp. 490-509. Page 500. ↵

[cxiii] Azevedo, M. J., and Nnadozie, E. U. 1998. Chad: A Nation in Search of Its Future. Westwind Press: Oxford. Page 52. ↵

[cxiv] Ibid, ↵

[cxv] Ibid. ↵

[cxvi] Ibid. ↵

[cxvii] Ibid. ↵

[cxviii] Ibid. ↵

[cxix] Ibid. ↵

[cxx] Ibid. Page 53. ↵

[cxxi] Ibid. ↵

[cxxii] Ibid. ↵

[cxxiii] Ibid. ↵

[cxxiv] Ibid. Page 54. ↵

[cxxv] Ibid. ↵

[cxxvi] Ibid. Page 56. ↵

[cxxvii] Ibid. ↵

[cxxviii] Ibid. Page 57. ↵

[cxxix] Ibid. ↵

[cxxx] Ibid. Page 60. ↵

[cxxxi] Ibid. Page 62. ↵

[cxxxii] Ibid. ↵

[cxxxiii] Ibid. ↵

[cxxxiv] Human Rights Watch. 2011. World Report 2011: Chad. Events of 2010. https://www.hrw.org/node/259443 ↵

[cxxxv] BBC News. “Hissene Habre: Chad's ex-ruler convicted of crimes against humanity” http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-36411466. ↵

[cxxxvi] Human Rights Watch. 2011. World Report 2011: Chad. Events of 2010. https://www.hrw.org/node/259443 ↵

[cxxxvii] Ibid. ↵

[cxxxviii] BBC News. 7 April 2016. “Chad profile – Timeline”. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-1316469 ↵

[cxxxix] Hancock, Stephanie. 2005. “Chad in 'state of war' with Sudan” in BBC News Friday, 23 December 2005. ↵

[cxl] Human Rights Watch. 2011. World Report 2011: Chad. Events of 2010. https://www.hrw.org/node/259443 ↵

[cxli] Ibid. ↵

[cxlii] BBC News. 7 April 2016. “Chad profile – Timeline”. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-1316469. ↵