The Empire of Mali was one of the largest empires in West African History, and at its height, it spanned from the Atlantic Coast to central parts of the Sahara desert [i]. The Empire was founded in 1235 CE by the legendary King Sundiata [ii] and lasted until the early 1600s CE [iii]. The Empire’s most famous ruler was named Mansa Musa, and chroniclers of the times wrote that when he travelled to Mecca on a pilgrimage he distributed so much gold that he caused great inflation lasting a decade [iv].

History

The Mali Empire arose with the consolidation of several small Malinké Kingdoms in Ghana around the areas of the upper Niger River [v]. Most of what is known about the Empire of Mali’s early history was collected by Arabic scholars in the 1300s and 1400s [vi]. A King named Sumanguru Kanté ruled the Susu Kingdom, which had conquered the Malinké people in the early 13th century [vii]. The King known as Sundiata (also spelt Sunjata) organised the Malinké resistance against the Susu Kingdom [viii], and Sundiata is believed by many historians, such as Conrad David and Innes Gordon, to have founded Mali when he defeated Sumanguru Kanté in 1235 [ix] [x].

The development of the empire began in its capital city of Niani, which was also coincidentally the birthplace of the empire’s founder and King Sundiata [xi]. Sundiata built a vast empire that stretched from the Atlantic Coast south of the Senegal River to Goa on the east of the Middle Niger bend.

Economy and Society in the Empire of Mali

The Mali Empire consisted of outlying areas and small kingdoms. All these Kingdoms pledged allegiance to Mali by offering annual tributes in the form of rice, millet, lances and arrows [xii]. Mali prospered from taxes collected from its citizens, and all goods brought in and out of the Empire were heavily taxed while all gold nuggets belonged to the King. However, gold dust could be traded and at certain times gold dust was used as currency together with salt and cotton cloth [xiii]. Cowrie shells from the Indian Ocean were later used as currency in the internal trade of Western Sahara [xiv].

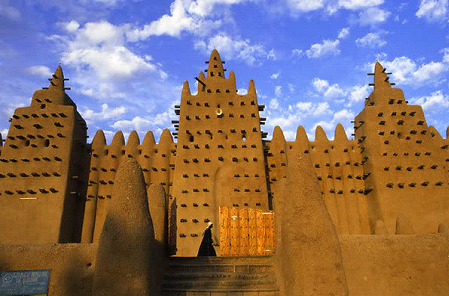

Mali, and especially the city of Timbuktu, was famous a centre of learning and spectacular architecture [xv] such as the Sankara Madrassa - a great centre of learning - and the University of Sankore which continued to produce a great many astronomers, scholars and engineers long after the end of the Empire of Mali. French colonial occupation is considered to have contributed to the University’s decline in its quality of education [xvi].

While Mali was a monarchy ruled by the Mansa or Master, much of the state power was in the hands of court officials [xvii]. This meant that the Empire could survive several periods of instability and a series of bad rulers. The Empire of Mali was also a multi-ethnic and multi-linguistic empire, and Islam was the dominant religion [xviii].

Leadership

Mali’s rulers adopted the title of ‘Mansa’ [xix]. Mali’s founder, Sundiata, firmly established himself as a strong leader in both the religious and secular sense [xx], claiming that he had a direct link to spirits of the land, thus making him the guardian of the ancestors. His empire extended from the fringes of the forest in the southwest through the grassland country of the Malinké to the Sahel and Southern Sahara ports of the Walatta and Tandmekka [xxi], and Arabic scholars estimate that Sundiata ruled for about 25 years and died in 1255 [xxii].

Despite the great extent of the Empire of Mali it was often plagued by insufficient leadership [xxiii]. Yet Sundiata’s son Mansa Wali [xxiv], who became the next King, is considered to have been one of the most powerful rulers of Mali [xxv]. Mansa Wali would, in turn, be succeeded by his brother Wati, who was succeeded by his brother called Kahlifa [xxvi]. Kahlifa was seen as a particularly bad ruler, and some chroniclers describe how he would use bows and arrows to kill people for entertainment [xxvii]. Because of his misrule, Kahlifa was deposed and replaced by a grandchild of Sundiata named Abu Bakr [xxviii]. Abu Bakr had been adopted by Sundiata as a son, although he was a grandchild and the son of Sundiata's daughter, which would have greatly strengthened his claim to the throne [xxix].

The leadership trouble in the Malian Empire would continue after the ascension of Abu Bakr. Abu Bakr was deposed in a coup by a man named Sakura, who was either a slave [xxx] or a military commander [xxxi]. The low stature of Sakura perhaps implies that the royal family had lost much of its popularity amongst the common people [xxxii]. Sakura’s reign, however, would also be a troubled one; after he had converted to Islam, Sakura undertook a pilgrimage to Mecca but was killed by the Danakil people [xxxiii] during his return journey while in the city of Tadjoura [xxxiv]. It is disputed why Sakura was in Tadjoura, as it was not a natural route to take when returning from Mecca to Mali, and also for what reasons he was killed [xxxv]. Some suggest that he was killed because the Danakil wanted to steal his gold [xxxvi].

Sakura’s rise to power also shows us that the ruling family, and the Mansa, had limited power in the Empire of Mali and that the officers of the court wielded significant power [xxxvii] in comparison. The Empire of Mali was organised into provinces with a strict hierarchical structure [xxxviii] in which each province had a Governor, and each town had a mayor or mochrif [xxxix]. Large armies were deployed to stop any rebellions in the smaller kingdoms and to safeguard the many trade routes [xl]. The decentralisation of power to lower levels of government bureaucracy through court officers, together with a strict hierarchical structure, was part of why the Malian Empire was so stable despite a series of bad rulers [xli]. Despite squabbles within the ruling family, the devolution of state administrative power through lower structures meant that the Empire could function quite well. In times of good rulers, the Empire would expand its territory, rendering it one of the largest Empires in West African history [xlii].

The famous Mansa Musa

It was in this context that the Empire of Mali’s most famous ruler, Mansa Musa, ascended to the throne. It is debated by historians whether Mansa Musa was the grandson of one of Sundiata’s brothers, thus making him Sundiata’s grand-nephew, or if he was the grandson of Abu Bakr [xliii]. What is known is that Mansa Musa converted to Islam and underwent a pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324, accompanied by 60 000 individuals and large quantities of gold [xliv]. His generosity was supposedly so great that by the time he left Mecca he had used every piece of gold he had taken with him, and had to borrow money for the return trip [xlv].

Mansa Musa was known to be a wise and efficient ruler, and one of his greatest accomplishments was his commission of some of the greatest buildings of Timbuktu. In 1327 the Great Mosque in Timbuktu was constructed [xlvi] and Timbuktu would later become a centre of learning [xlvii]. At the end of Mansa Musa’s reign, he had built and funded the Sankara Madrassa, which subsequently becomes one of the greatest centres of learning in the Islamic world, and the greatest library in Africa at the time [xlviii]. The Sankara Madrassa is estimated to have housed between 250 000 and 700 000 manuscripts, making it the largest library in Africa since the Great Library of Alexandria [xlix]. Some sources claim that during his reign Mansa Musa conquered 24 cities with its surrounding land, thus expanding the empire greatly [l]. Mansa Musa is estimated to have died in 1337, and would pass the title of Mansa to his son, Mansa Maghan [li].

The Great Mosque of Timbuktu

The Great Mosque of Timbuktu

The decline of the Mali Empire

The period of 1360 – 1390 was a time of troubles for the Empire of Mali [lii]. The Empire suffered under several bad rulers with short reigns [liii]. The throne changed hands between several members of the ruling family and was at one point seized by a man named Mahmud, who was not from Mali nor part of the ruling family [liv]. Eventually, Mansa Mari Djata II managed to regain the throne for the ruling dynasty, but his despotic rule ruined the state [lv]. As in previous years, it was a court official who brought the Empire back on track after a series of bad rulers. Mari Djarta, a ‘wazir’ (minister), took power and ruled, essentially acting as regent, through King Mansa Musa II [lvi]. During the reign of Mari Djarta (also known as Mari Djarta III) the Empire of Mali would restore some of the power that it had lost during the preceding 30 years of misrule and civil war [lvii].

Mansa Musa II died in 1387 and was succeeded by his brother Mansa Magha II, who would also be the puppet of powerful court officials [lviii]. After a year Mansa Musa II was killed, thus ending the line of kings which descended from Mansa Musa I [lix]. This triggered the decline of the Empire of Mali and in 1433 the city was conquered by Tuareg nomads [lx]. For the next 100 years the Empire would slowly give way to the Songhay conquerors from the east, and by the 1500s it had been reduced to only its Malinké core lands [lxi]. During the 17th century Mali had broken into a number of minor independent chiefdoms and thus the Mali Empire was no longer the superpower it had been in its prime [lxii].

Endnotes

[i] Conrad, David C. 2009. Great Empires of the Past. Empires of Medieval West Africa: Ghana, Mali, and Songhay. New York: Facts on File, Inc. Page 39. ↵

[ii] Innes, Gordon. 1974. Sunjata: Three Mandinke Versions. School of Oriental and African Studies University of London. Male Street, London. Page 1. ↵

[iii] Conrad, David C. 2009. Great Empires of the Past. Empires of Medieval West Africa: Ghana, Mali, and Songhay. New York: Facts on File, Inc. Page 59. ↵

[iv] Ibid. ↵

[v] Conrad, David C. 2009. Great Empires of the Past. Empires of Medieval West Africa: Ghana, Mali, and Songhay. New York: Facts on File, Inc. Page 39. ↵

[vi] Levtzion, N. 1963. “The Thirteenth- and Fourteenth- Century Kings of Mali” in Journalof African History, IV, 3 (I963), pp. 34I-353. Page 341. ↵

[vii] C. 2009. Great Empires of the Past. Empires of Medieval West Africa: Ghana, Mali, and Songhay. New York: Facts on File, Inc. Page 42. ↵

[viii] Ibid. Page 17. ↵

[ix] Gordon. 1974. Sunjata: Three Mandinke Versions. School of Oriental and African Studies University of London. Male Street, London. Page 1. ↵

[x] Innes, Gordon. 1974. Sunjata: Three Mandinke Versions. School of Oriental and African Studies University of London. Male Street, London. Page 1. ↵

[xi] Conrad, David C. 2009. Great Empires of the Past. Empires of Medieval West Africa: Ghana, Mali, and Songhay. New York: Facts on File, Inc. Page 34. ↵

[xii] Togola, Téréba. 1996. “Iron Age Occupation in the Méma Region, Mali” in The African Archaeological Review, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Jun., 1996), pp. 91-110. Page 95. ↵

[xiii] Conrad, David C. 2009. Great Empires of the Past. Empires of Medieval West Africa: Ghana, Mali, and Songhay. New York: Facts on File, Inc. Page 34. ↵

[xiv] Ibid. ↵

[xv] Shuriye, Abdi O. and Ibrahim, Dauda Sh. 2013. “Timbuktu Civilization and its Significance in Islamic History” in Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy Vol 4 No 11 October 2013. Page 697. ↵

[xvi] Ibid. Page 698. ↵

[xvii] Levtzion, N. 1963. “The Thirteenth- and Fourteenth- Century Kings of Mali” in Journal of African History, IV, 3 (I963), pp. 34I-353. Page 350. ↵

[xviii] Conrad, David C. 2009. Great Empires of the Past. Empires of Medieval West Africa: Ghana, Mali, and Songhay. New York: Facts on File, Inc. Page 34. ↵

[ixx] David C. 2009. Great Empires of the Past. Empires of Medieval West Africa: Ghana, Mali, and Songhay. New York: Facts on File, Inc. Page 45. ↵

[xx] Ibid. ↵

[xxi] Ibid. ↵

[xxii] Ibid. Page 44. ↵

[xxiii] Ibid. ↵

[xxiv] Ibid.. ↵

[xxv] Levtzion, N. 1963. “The Thirteenth- and Fourteenth- Century Kings of Mali” in Journal ↵

[xxvi] Ibid. ↵

[xxvii] Ibid. ↵

[xxviii] Ibid. Page 344. ↵

[ixxx] Ibid. ↵

[xxx] Ibid. Page 345.. ↵

[xxxi] C. 2009. Great Empires of the Past. Empires of Medieval West Africa: Ghana, Mali, and Songhay. New York: Facts on File, Inc. Page 45. ↵

[xxxii] Ibid. ↵

[xxxiii] Beckingham, C.F. 1953. “Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies” in African Studies. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies / Volume 15 / Issue 02 / June 1953, pp 391-392. ↵

[xxxiv] Levtzion, N. 1963. “The Thirteenth- and Fourteenth- Century Kings of Mali” in Journal of African History, IV, 3 (I963), pp. 34I-353. Page 345. ↵

[xxxv] Ibid. ↵

[xxxvi] Ibid. ↵

[xxxvii] Conrad, David C. 2009. Great Empires of the Past. Empires of Medieval West Africa: Ghana, Mali, and Songhay. New York: Facts on File, Inc. Page 45. ↵

[xxxviii] Togola, Téréba. 1996. “Iron Age Occupation in the Méma Region, Mali” in The African Archaeological Review, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Jun., 1996), pp. 91-110. Page 95. ↵

[xxxix] McDowell, Linda and Mackay, Marilyn. 2005. Teacher's Guide for World History Societies of the Past. Portage and Main Press. Winnipeg, Canada. Page 246. ↵

[xl] Ibid. ↵

[xli] Conrad, David C. 2009. Great Empires of the Past. Empires of Medieval West Africa: Ghana, Mali, and Songhay. New York: Facts on File, Inc. Page 45. ↵

[xlii] Ibid. Page 17. ↵

[xliii] Levtzion, N. 1963. “The Thirteenth- and Fourteenth- Century Kings of Mali” in Journal of African History, IV, 3 (I963), pp. 34I-353. Page 347. ↵

[xliv] C. 2009. Great Empires of the Past. Empires of Medieval West Africa: Ghana, Mali, and Songhay. New York: Facts on File, Inc. Page 49. ↵

[xlv] Ibid. ↵

[xlvi] Ibid. ↵

[xlvii] Ibid. ↵

[xlviii] Shuriye, Abdi O. and Ibrahim, Dauda Sh. 2013. “Timbuktu Civilization and its Significance in Islamic History” in Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy Vol 4 No 11 October 2013. Page 697. ↵

[xlix] Ibid. ↵

[l] Conrad, David C. 2009. Great Empires of the Past. Empires of Medieval West Africa: Ghana, Mali, and Songhay. New York: Facts on File, Inc. Page 45. ↵

[li] Levtzion, N. 1963. “The Thirteenth- and Fourteenth- Century Kings of Mali” in Journal of African History, IV, 3 (I963), pp. 34I-353. Page 350. ↵

[lii] Ibid. ↵

[liii] Ibid. Page 351. ↵

[liv] Ibid. ↵

[lv] Ibid. ↵

[lvi] Ibid. ↵

[lvii] Conrad, David C. 2009. Great Empires of the Past. Empires of Medieval West Africa: Ghana, Mali, and Songhay. New York: Facts on File, Inc. Page 55. ↵

[lviii] Ibid. Page 56. ↵

[lix] Ibid. ↵

[lx] Hunwick, John O. 2000. "Timbuktu" in Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume X (2nd ed.), Leiden: Brill, pp. 508–510. Page 508. ↵

[lxi] Conrad, David C. 2009. Great Empires of the Past. Empires of Medieval West Africa: Ghana, Mali, and Songhay. New York: Facts on File, Inc. Page 59. ↵

[lxii] Ibid. ↵