The history of Queen Njinga (or Nzinga) of Ndongo/Matamba is contested. Portuguese colonial historians and missionaries would emphasise her conversion to Catholicism and her participation in the slave trade. Angolan nationalist historians would focus her anti-colonial activities and her long struggle against colonial conquest. What is certain, however, is that Queen Njinga's rise to power as a woman of that time was nothing short of revolutionary and that her actions as a warrior, diplomat and nation builder would be an inspiration to those who would later fight for Angolan independence. The Kingdom she created would be a refuge for runaway slaves and a safe haven from European conquest for over two centuries after her death. Her actions as a women defying both male and colonial domination has also made her an important inspiration for more recent African feminists [1].

Njinga was born around 1582 in the Kingdom of Ndongo in present-day-Angola [2]. The Kingdom of Ndongo was established by the Mbundu people living on the Western coast of Central Africa. The ruler of Ndongo was titled the Ngola, and acted as a monarch and ruling figurehead. It is from the Ngola title that the state of Angola would later derive its name [3]. Njinga was part of the royal dynasty and was the daughter of Ngola Kia Samba and Guenguela Cakomb [4]. Her brother would become the Ngola Mbandi after her father and rule Ndongo from 1618 to 1624.

The Kingdom of Ndongo started out as a vassal state to the Kingdom of Kongo, but broke free in the early 1500s. The Ngola who ruled the Kingdom of Ndongo would be appointed after an election process where in which various members of the ruling dynasty were considered eligible to be the next king [5]. The Kingship of Ngola was negotiated through alliances and personal relationships and not a position of absolute power. Once a new Ngola was chosen from one of the dominant noble families, or lineages, that person was then expected to redistribute wealth to his/her followers and reward them for their support [6]. It was highly unusual for a woman to be elected to the position of Ngola and Njinga's rise to power was exceptional and was the product of brilliant political manoeuvring.

Njinga was born in a time of turmoil for for the Mbundu people. In 1575 the Portuguese had set up their first outpost in what would eventually be the colony of Angola. This outpost was set up on the island of Luanda and it would be a starting point for a long lasting conflict between the Ndongo and the Portuguese. By the time when Njinga was born in 1582 the Portuguese and the Ndongo were engaged in a full blown war. From the 1580s Portugal was in constant war with the Kingdom of Ndongo in an effort to conquer more land and acquire more slaves [7]. In the early 1600s the Portuguese allied with the Imbangala people. The Imbangala were basically armed bands of people travelling across central Africa, who were known for their guerilla warfare and their fighting skills. The combined onslaught of the Imbangala and the Portuguese caused several great losses for the Ndongo in 1618, and it was close to bringing down the whole Kingdom.

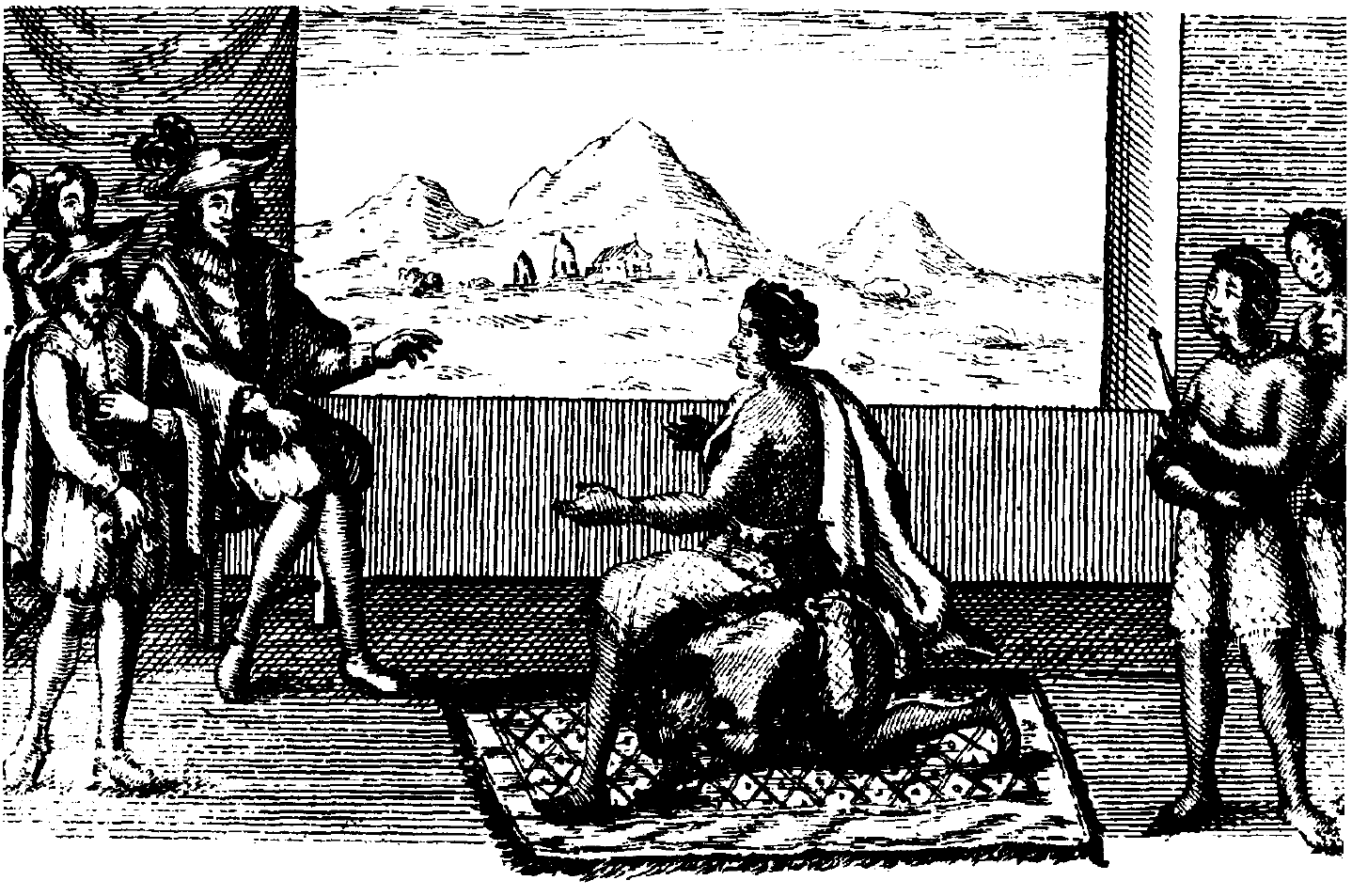

Not so much is known about Njinga's early life, but in 1622 her brother, the Ngola Mbandi, sent her to negotiate a peace treaty with the Portuguese [8]. The story goes that when Njinga entered the room to negotiate with the Portuguese Governor he was sitting in a chair while she was expected to sit on a mat on the floor. Not wanting to be seated lower than her opposition she had a servant kneel down behind her so she could negotiate on equal terms [9]. For months she stayed in Luanda and discussed a possible peace treaty with the Portuguese. To improve her negotiating position she allowed herself to be baptised as a Catholic and took the Christian name Ana de Sousa [10]. Njinga managed to negotiate a peace treaty with the Portuguese, but it was broken by the Portuguese almost as soon as she had left Luanda. Some historians argue that her meeting with the Portuguese would later aid her in her ascent to power, as it established her as a major contender for the title of Ngola [11].

Njinga sitting on top of her servant and negotiating with the Portuguese governor of Luanda Image source

Njinga sitting on top of her servant and negotiating with the Portuguese governor of Luanda Image source

In 1624 Njinga's brother, the Ngola Mbandi, died under suspicious circumstances [12]. Njinga and Mbandi had over the years had a strained relationship. First, they were not technically siblings as they had different mothers, and the Mbundu people tracing their descent through women (matrilineal) would not be a part of the same lineage [13]. Njinga's mother was also said to have been a slave which would further diminish her status in the eyes of other royals at the time. In addition to this it is believed that Mbandi had murdered Njinga's son when he ascended the throne in 1618 [14]. Although it was highly contested by many of the noble lineages Njinga was elected, first as regent for her nephew after her brother's death, and later as Ngola after her nephews early demise. She then took the name and title Ngola Njinga Mbandi. After effectively becoming Queen of the Kingdom of Ndongo she negotiated a second treaty with the Portuguese in 1624 allowing for the Portuguese to trade (including slavery) and missionary work in return for the Portuguese respecting the territorial integrity of Ndongo and demolishing a Portuguese fort which was within Ndongo territory [15].

The treaty quickly fell apart however. Queen Njinga harboured runaway slaves in her lands breaking her part of the treaty, while the Portuguese Governor never followed through on the removal of the fortress on Ndongo territory. Looking at how quickly the Portuguese had broken their first treaty Njinga must have been suspicious of Portuguese intentions to keep their promises with the second treaty. To gain control over the internal politics of the Kingdom of Ndongo the Portuguese began to back rival claimants to the throne and pushed them to rebel against Njinga [16]. To fight both the Portuguese and her domestic rivals she would need to increase her military strength [17]. To do this she enlisted one of the Imbangala war bands in the area to help her. After the end of the Portuguese-Imbangala alliance in 1619 most of the Imbangala had moved east and settled under the name of Kasanje [18]. South of the Kwanza river there was, however, a large group of Imbangala called Kanza. Through a symbolic marriage and much political manoeuvring she took control over the band and then had her Mbundu followers trained in Imbangala martial arts [19]. This gave her not only a powerful army, but also a great retreat as she could now flee south of Kwanza where the Portuguese would not dare to follow. Nzinga set up camp on the Kindonga Islands, which would become a permanent position for her to retreat to when she was being attacked by the Portuguese.

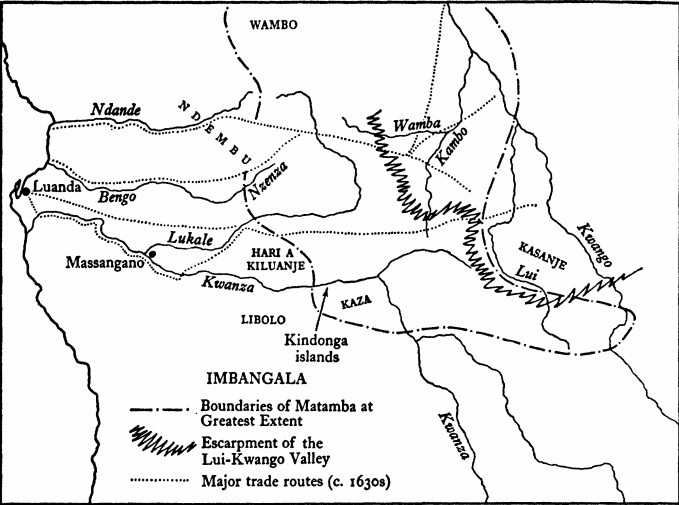

Between 1626 and 1629, Queen Njinga would personally lead many raids against the Portuguese who was invading the Ndongo lands [20]. At the same time she also fought the Portuguese puppet King of Ndongo, Ngola Hari a Kiluanje. While Ngola Hari a Kiluanje died in the late 1620s his son would continue to rule over Ndongo as a puppet of the Portuguese for the next 25 years. By 1629 she was abandoned by her Imbangala allies, unable to effectively fight the Portuguese she went east to the Kingdom of Matamba [21]. With the armies she had left she conquered the Kingdom of Matamba, which was severely weakened by Kasanje incursions, and in 1631 joined the two Kingdoms of Matamba and Ndongo (although she effectively only held control over Matamba at this point). By the 1640s she had expanded the borders of Kingdom of Matamba to one of the largest in the region [22]. In the mid 1630s Njinga defeated the Ngola Hari a Kiluanje and cut of Portuguese slaving raids attempting to go further inland [23]. It should be noted that, as most successful rulers in the area at the times, part of Queen Njinga's success was because of the wealth she gained from selling her captured enemies as slaves [24].

The Matamba/Ndongo Kingdom in the 1630s. Source: Miller, Joseph C. 1975. “Njinga of Matamba in a New Perspective” in The Journal of African History, Vol. 16, No. 2 (1975), Cambridge University Press.

The Matamba/Ndongo Kingdom in the 1630s. Source: Miller, Joseph C. 1975. “Njinga of Matamba in a New Perspective” in The Journal of African History, Vol. 16, No. 2 (1975), Cambridge University Press.

In the 1640s events in Europe would aid Njinga's struggle against the Portuguese. The Dutch and the Portuguese were at war over the Protestant Reformation happening on the European continent, and in 1641 an armada of Dutch ships attacked and seized Luanda [25]. An alliance was then formed between the Kingdom of Kongo, Njinga's Kingdom of Ndongo/Matamba, and the Dutch, in order to expel the Portuguese from their coastal fortresses [26]. For seven years the war raged on between the Afro-Dutch alliance and the Portuguese colonialists, and by 1647 the Portuguese presence was almost erased completely. The tide would turn in 1648 however, as an armada from Brazil came to the assistance of the Portuguese forces under siege in the fortress in Massangano. The Dutch quickly made peace with the Portuguese after this. Queen Njinga was unable to maintain the war effort on her own so she retreated back to Matamba [27].

Once she could regroup Njinga would continue her fighting against the Portuguese for another six years until 1654 [28]. In 1654 she began to negotiate for peace with the Portuguese and in 1656 they reached an agreement. The Portuguese would acknowledge Njinga as ruler of both Matamba and Ndongo (to the disappointment of their puppet king), in return she opened her Kingdom up to Portuguese merchants and slave traders, and yielded control over the trade route from Matamba to the sea. To secure the peace treaty she reaffirmed her belief in Catholicism [29]. The treaty would affirm the sovereignty of her state and her people, but there were also major concessions, such as a tribute of slaves which was to be paid to the Portuguese annually [30]. During the 30 year long war with the Portuguese Queen Njinga had personally led her armies in most of the battles they fought [31].

At the end of her life Queen Njinga became more devoutly Catholic. Some academics argue that this was for strategic reasons to cement Portuguese support for her rule and silence any domestic dissent [32]. According to some sources throughout the 1640s she had taken several men as husbands and many at the same time, these relationships soon developed into a kind of harem of male concubines [33]. Some academics argue that the reason for adoption of concubines was to adopt typical masculine behaviours to increase her legitimacy in the eyes of the other noble lineages [34]. In any case, after her re-affirmation to Catholicism in 1656 she gave up her concubines and married one man [35]. After the peace treaty with Portugal her followers was also told to give up their Imbangala ways, this meant that people would settle in villages instead of mobile camps, and women would be allowed to give birth to and raise children.

In 1663 Queen Njinga died at the age of 81 years old [36]. Eyewitnesses who had seen her lead military parades 1662 said that she was a still a striking figure who still retained her martial prowess. Njinga's last remaining years was spent paving the way for her successor and to remove her Imbangala allies from the centre of power. By the time of her death Njinga had cemented the idea that a woman could rule the Mbundu people. She was succeeded by her sister Barbara who ruled until 1666 [37]. After Queen Barbara the Kingdom of Ndongo and Matamba would have another four female rulers in the period between 1666 and 1767 [38]. There are few countries in the world who so consistently was ruled by a woman as Ndongo-Matamba was in the time after Queen Njinga. While the Ndongo lands were occupied the Portuguese in 1671 the Matamba part of the Kingdom would retain its independence until the early 1900s [39].

Endnotes

[1] Ifi Amadiume, “African Women: Voicing Feminisms and Democratice Futures” in Macalester International: Vol. 10, Article 9, Spring 2001. Page 55. ↵

[2] Linda Heywod and Louis Madureira (translation), “Queen Njinga Mbandi Ana de Sousa of Ndongo/Matamba: African Leadership, Diplomacy, and Ideology, 1620s-1650s” in Afro-Latino Voices: Shorter Edition: Translations of Early Modern Ibero-Atlantic Narratives, Kathryn Joy McKnight, Leo J. Garofalo (eds), (2015), Hackett Publishing Company: Indianapolis. Page 26. ↵

[3] James W. Martin. Historical Dictionary of Angola (Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc: Plymouth, 2011). Page xxxi. ↵

[4] Hettie V. Williams, “Queen Njinga (Njinga Mbande)” in Alexander, Leslie M.; Rucker, Walter C. Encyclopedia of African American History, (2010), Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. Page 83. ↵

[5] John Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400-1800, (1998), New York: Cambridge University Press. Page 83. ↵

[6] Joseph C. Miller, “Njinga of Matamba in a New Perspective” in Source: The Journal of African History, Vol. 16, No. 2 (1975), Cambridge University Press. Page 204. ↵

[7] Linda Heywod and Louis Madureira (translation), “Queen Njinga Mbandi Ana de Sousa of Ndongo/Matamba: African Leadership, Diplomacy, and Ideology, 1620s-1650s” in Afro-Latino Voices: Shorter Edition: Translations of Early Modern Ibero-Atlantic Narratives, Kathryn Joy McKnight, Leo J. Garofalo (eds), (2015), Hackett Publishing Company: Indianapolis. Page 26. ↵

[8] Ibid. ↵

[9] Hettie V. Williams, “Queen Njinga (Njinga Mbande)” in Alexander, Leslie M.; Rucker, Walter C. Encyclopedia of African American History, (2010), Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. Page 83. ↵

[10] Joseph C. Miller, “Njinga of Matamba in a New Perspective” in Source: The Journal of African History, Vol. 16, No. 2 (1975), Cambridge University Press. Page 207. ↵

[11] Ibid. ↵

[12] Hettie V. Williams, “Queen Njinga (Njinga Mbande)” in Alexander, Leslie M.; Rucker, Walter C. Encyclopedia of African American History, (2010), Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. Page 84. ↵

[13] Joseph C. Miller, “Njinga of Matamba in a New Perspective” in Source: The Journal of African History, Vol. 16, No. 2 (1975), Cambridge University Press. Page 207. ↵

[14] Ibid. ↵

[15] Ibid. Page 208. ↵

[16] Ibid. ↵

[17] Linda Heywod and Louis Madureira (translation), “Queen Njinga Mbandi Ana de Sousa of Ndongo/Matamba: African Leadership, Diplomacy, and Ideology, 1620s-1650s” in Afro-Latino Voices: Shorter Edition: Translations of Early Modern Ibero-Atlantic Narratives, Kathryn Joy McKnight, Leo J. Garofalo (eds), (2015), Hackett Publishing Company: Indianapolis. Page 26. ↵

[18] Joseph C. Miller, “Njinga of Matamba in a New Perspective” in Source: The Journal of African History, Vol. 16, No. 2 (1975), Cambridge University Press. Page 208. ↵

[19] Ibid. ↵

[20] Linda Heywod and Louis Madureira (translation), “Queen Njinga Mbandi Ana de Sousa of Ndongo/Matamba: African Leadership, Diplomacy, and Ideology, 1620s-1650s” in Afro-Latino Voices: Shorter Edition: Translations of Early Modern Ibero-Atlantic Narratives, Kathryn Joy McKnight, Leo J. Garofalo (eds), (2015), Hackett Publishing Company: Indianapolis. Page 27. ↵

[21] Joseph C. Miller, “Njinga of Matamba in a New Perspective” in Source: The Journal of African History, Vol. 16, No. 2 (1975), Cambridge University Press. Page 209. ↵

[22] Ibid. Page 210. ↵

[23] Ibid. ↵

[24] Ibid. ↵

[25] Linda Heywod and Louis Madureira (translation), “Queen Njinga Mbandi Ana de Sousa of Ndongo/Matamba: African Leadership, Diplomacy, and Ideology, 1620s-1650s” in Afro-Latino Voices: Shorter Edition: Translations of Early Modern Ibero-Atlantic Narratives, Kathryn Joy McKnight, Leo J. Garofalo (eds), (2015), Hackett Publishing Company: Indianapolis. Page 27. ↵

[26] Ibid. ↵

[27] Ibid. ↵

[28] Ibid. ↵

[29] Joseph C. Miller, “Njinga of Matamba in a New Perspective” in Source: The Journal of African History, Vol. 16, No. 2 (1975), Cambridge University Press. Page 212. ↵

[30] Ibid. ↵

[31] Linda Heywod and Louis Madureira (translation), “Queen Njinga Mbandi Ana de Sousa of Ndongo/Matamba: African Leadership, Diplomacy, and Ideology, 1620s-1650s” in Afro-Latino Voices: Shorter Edition: Translations of Early Modern Ibero-Atlantic Narratives, Kathryn Joy McKnight, Leo J. Garofalo (eds), (2015), Hackett Publishing Company: Indianapolis. Page 26. ↵

[32] Joseph C. Miller, “Njinga of Matamba in a New Perspective” in Source: The Journal of African History, Vol. 16, No. 2 (1975), Cambridge University Press. Page 212. ↵

[33] John Thornton, “Legitimacy and Political Power: Queen Njinga, 1624-1663” in The Journal of African History Vol. 32, No. 1 (1991), pp. 25-40. Page 38. ↵

[34] Ibid. ↵

[35] Linda Heywod and Louis Madureira (translation), “Queen Njinga Mbandi Ana de Sousa of Ndongo/Matamba: African Leadership, Diplomacy, and Ideology, 1620s-1650s” in Afro-Latino Voices: Shorter Edition: Translations of Early Modern Ibero-Atlantic Narratives, Kathryn Joy McKnight, Leo J. Garofalo (eds), (2015), Hackett Publishing Company: Indianapolis. Page 27. ↵

[36] Ibid. ↵

[37] John Thornton, “Legitimacy and Political Power: Queen Njinga, 1624-1663” in The Journal of African History Vol. 32, No. 1 (1991), pp. 25-40. Page 40. ↵

[38] Ibid. ↵

[39] Joseph C. Miller, “Njinga of Matamba in a New Perspective” in Source: The Journal of African History, Vol. 16, No. 2 (1975), Cambridge University Press. Page 215. ↵