World War II (1939 to 1945) was the most devastating war in history, accounting for between 50 million to 80 million deaths. What made the war significant was the sheer scale of the conflict and the gross violation of Human Rights. All the great powers were involved as the conflict between the Axis and the Allies stretched across all five continents.

Section 1 (The rise of Nazi Germany) begins by looking at the aftermath of WW I, focusing on the signing of the Treaty of Versailles (1919) and the reparations and concessions made by Germany. The rise of Hitler and Nazism will be examined, as well as how the Great Depression and the failure of democracy in the Weimar Republic boosted Hitler’s popularity. Finally, this section will show how Germany became a Fascist state, through its suppression of Jewish citizens and the persecution of its political opponents.

Section 2 (World War II: Europe) describes the foreign policy of Nazism and how it lead to the outbreak of WWII. The Axis vs. Allies will be presented and explained. This section will also focus on Human Rights abuse, specifically extermination camps and genocide, the Holocaust and the ‘Final Solution’. Examples of resistance movements such as the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising will be provided and the end of WWII will be explained.

Section 3(World War II in the Pacific) will focus on the Pacific, looking at the conflict between the USA and Japan, known as Pearl Harbour. This will highlight forced movements and human rights abuses committed by both parties during WWII.

World War II

The Second World War was the most widespread and deadliest war in history, involving more than 30 countries and resulting in more than 50 million military and civilian deaths. Sparked by Adolf Hitler’s invasion of Poland in 1939, the war would drag on for six deadly years until the final Allied defeat of both Nazi Germany and Japan in 1945.

This lesson focuses on how Nazi Germany came to power, how the World War II took place in Europe, and how the World War II occurred in the Pacific, as required by the CAPS Curriculum.

The Rise of Nazi Germany

Hitler along with his Nazi followers. Image source

Hitler along with his Nazi followers. Image source

In 1919, army veteran Adolf Hitler, frustrated by Germany’s defeat in World War which had left the nation economically depressed and politically unstable, joined an emerging political organization called the German Workers’ Party. Founded earlier that same year by a small group of men including locksmith Anton Drexler (1884-1942) and journalist Karl Harrer (1890-1926), the party promoted German nationalism and anti-Semitism, and felt that the Treaty of Versailles, the peace settlement that ended the war, was extremely unjust to Germany by burdening it with reparations it could never pay. In July 1921, he assumed leadership of the organization, which by then had been renamed the Nationalist Socialist German Workers’ (Nazi) Party. Throughout the 1920’s, Hitler gave speeches regarding different socio- economic problems, believing that if communists and Jews were driven from the nation, all Germany’s problems will be solved. His fiery speeches swelled the ranks of the Nazi Party, especially among young, economically disadvantaged Germans.

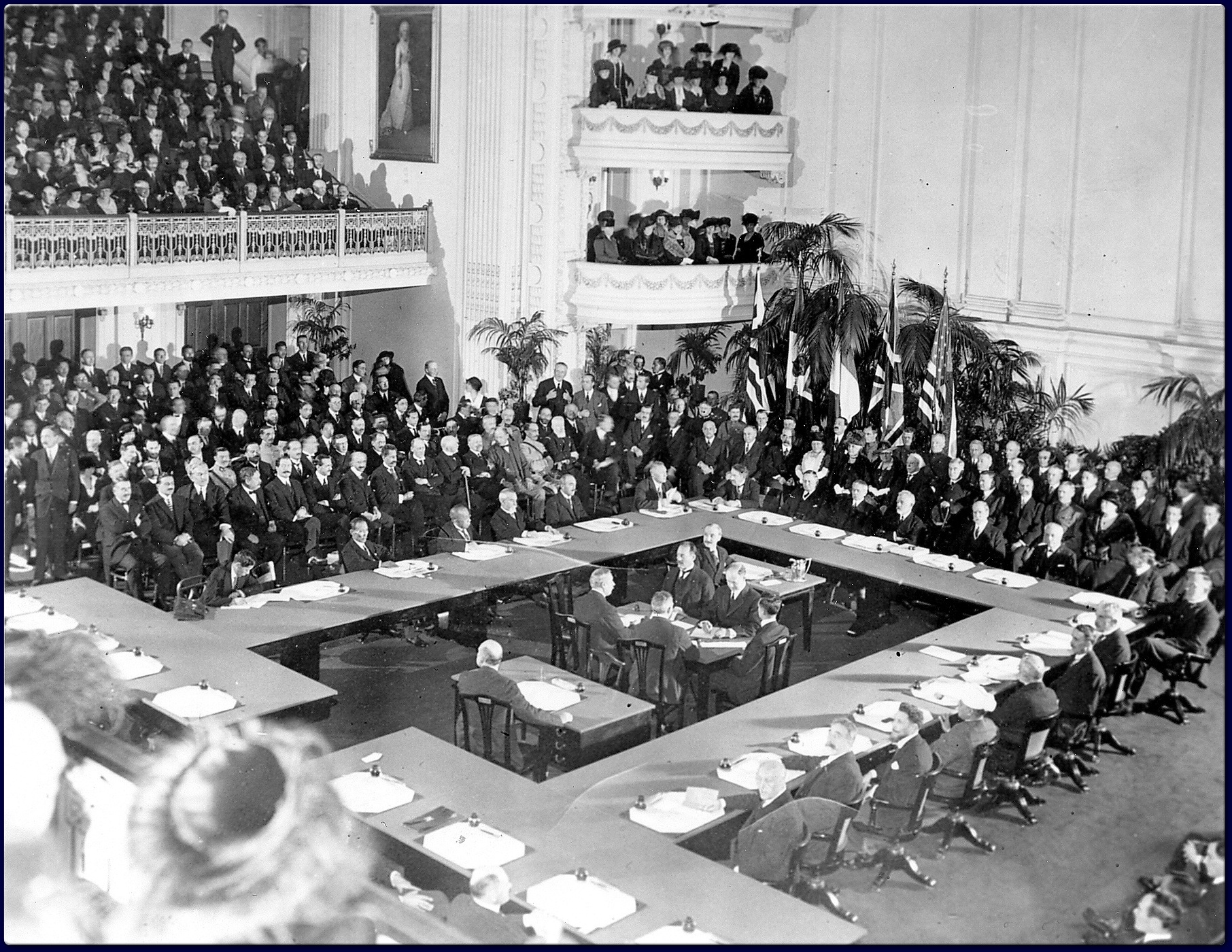

The signing of the Treaty of Versailles. Image source

The signing of the Treaty of Versailles. Image source

In 1929, Germany entered a period of severe economic depression and widespread unemployment. The Nazis exploited the situation by criticizing the ruling government and began to win elections. In January 1933, Hitler was appointed German chancellor and his Nazi government soon came to control every aspect of German life.

On 28 June 1919, the peace treaty that ended World War I was signed by Germany and the Allies at the Palace of Versailles near Paris. The Treaty of Versailles was the peace settlement with Germany; it was very harsh. Germany had to accept blame for starting the war; lose all of its colonies, lose most of its army, navy and all its air force, lose huge territories in Europe, and pay reparations of £6.6 billion.

The Germans despised the Treaty of Versailles and throughout the 1920s and 1930s German politicians tried to reverse the terms of the treaty. In the 1920s Hitler and the Nazis gained support as they promised to reverse the treaty. In the 1930s when the Nazis were in power, Hitler set about reversing these terms. Britain believed that Hitler should be allowed to do this. The policies of letting the Germans take back their lands and building their armed services, with a vague promise of future good behaviour, were called Appeasement.

In 1920 the German Workers' party was renamed the National Socialist German Workers, or Nazi, party; in 1921 it was reorganized with Hitler as chairman. He achieved leadership in the party (and later in Germany) largely due to his extraordinary skill as a speaker, holding large crowds spellbound by his oratory. Hitler made the party a paramilitary organization and won the support of such prominent nationalists as Field Marshal Ludendorff. Adolf Hitler's contempt for traditional German law had been manifest from his earliest days as leader of the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP). The NSDAP's Twenty-Five point programme of 1920 proposed that existing law 'be replaced by a German common law'. By implication the NSDAP believed that the primary purpose of law should be to serve a racially defined Aryan national community, enshrined in a 'strong central state power' that would replace the democratic Constitution of 1919. Hitler shared the Party's rejection of the principle of equality for all before the law.

The Great Depression was a worldwide economic slump that began as an American crisis. Germans were not so much reliant on exports as they were on American loans, which had been propping up the Weimar economy since 1924. No further loans were issued from late 1929, while American financiers began to call in existing loans. Despite its rapid growth, the German economy was not equipped for this retraction of cash and capital. Banks struggled to provide money and credit; in 1931 there were runs on German and Austrian banks and several of them folded. In 1930 the US, the largest purchaser of German industrial exports, put up tariff barriers to protect its own companies. German industrialists lost access to US markets and found credit almost impossible to obtain. Many industrial companies and factories either closed or shrank dramatically. By 1932 German industrial production was at 58 per cent of its 1928 levels. The effect of this decline was spiraling unemployment. By the end of 1929 around 1.5 million Germans were out of work; within a year this figure had more than doubled. By early 1933 unemployment in Germany had reached a staggering six million.

People line up outside the Postscheckamt in Berlin to withdraw their deposits in July 1931. Image source

People line up outside the Postscheckamt in Berlin to withdraw their deposits in July 1931. Image source

The effects this unemployment had on German society were devastating. While there were few shortages of food, millions of people found themselves without the means to obtain sustence. The children suffered worst, where thousands died from malnutrition and hunger-related diseases. Millions of industrial workers – who in 1928 had become the best-paid blue collar workers in Europe – spent a year or more in a state of inactiveness. But the Great Depression affected all classes in Germany, not just the factory workers. Unemployment was high among white-collar workers and the professional classes. A Chicago news correspondent in Berlin reported that “60 per cent of each new university graduating class was out of work”.

At the annual party rally held in Nuremberg in 1935, the Nazis announced new laws which institutionalized many of the racial theories prevalent in Nazi ideology. The laws excluded German Jews from Reich citizenship and prohibited them from marrying or having sexual relations with persons of "German or related blood." Ancillary ordinances to the laws disenfranchised Jews and deprived them of most political rights.

Between mid-1933 and the early 1940s, the Nazi regime passed dozens of laws and decrees that eroded the rights of Jews in Germany. Anyone who had three or four Jewish grandparents was defined as a Jew, regardless of whether that inpidual identified himself or herself as a Jew or belonged to the Jewish religious community. Weeks after Hitler became Chancellor, a campaign was launched to boycott all Jewish businesses where they were plastered with yellow Stars of David or with negative slogans. During this boycott some Jews were assaulted while others’ property was destroyed. Laws were passed to abolish the employment rights of Jews, and banned non- Aryans from having state jobs. This led to the prevention of Jewish judges, doctors, lawyers and teachers to be able to practice their professions. Some of these laws were seemingly insignificant, such as an April 1935 mandate banning Jews from flying the German flag; or a February 1942 order prohibiting Jews from owning pets. But other laws withdrew the voting rights of Jews, their access to education, their capacity to own businesses or to hold particular jobs. In 1934 Jews were banned from sitting university exams; in 1936 they were forbidden from using parks or public swimming pools and from owning electrical equipment, typewriters or bicycles. Jews were also subject to cultural and artistic restrictions, forcing hundreds to leave jobs in the theatre, cinema, cabaret and the visual arts. The summer of 1935 saw an escalation in spontaneous violence against Jewish people and property.

Jews in Germany wearing the Jewish star to identify them in public. Image source

Jews in Germany wearing the Jewish star to identify them in public. Image source

World War II in Europe

Germany started World War II by invading Poland on September 1, 1939. Britain and France responded by declaring war on Germany on September 3. Within a month, Poland was defeated by a combination of German and Soviet forces and was partitioned between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. German forces invaded Norway and Denmark on 9 April 1940. On May 10, 1940, Germany began its assault on Western Europe by invading the Low Countries (Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg), which had taken neutral positions in the war, as well as France. In July 1943, the Allies landed in Sicily and in September went ashore on the Italian mainland. On June 6, 1944, as part of a massive military operation, over 150,000 Allied soldiers landed in France, which was liberated by the end of August. The Soviets began an offensive on January 12, 1945, liberating western Poland and forcing Hungary (an Axis ally) to surrender. In mid-February 1945, the Allies bombed the German city of Dresden, killing approximately 35,000 civilians.

Adolf Hitler's government conducted a foreign policy aimed at the incorporation of ethnic Germans (Volksdeutsche) living outside German borders into the Reich; German domination of western Europe; and the acquisition of a vast new empire of "living space" (Lebensraum) in eastern Europe. The realization of German hegemony in Europe, Hitler calculated, would require war, especially in Eastern Europe.

A temporary deviation from Germany's normally anti-Communist foreign policy, this agreement allowed Hitler the freedom to attack Poland on September 1, 1939, without fear of Soviet intervention. Britain and France, Poland's allies, declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939. Hitler's aggressive foreign policy resulted in the outbreak of World War II.

Despite this, there was a good deal of anti-Nazi criticism, dissent and resistance between 1933 and 1939. Much of this was conducted in secret because of the expansive Nazi police state and the extensive powers of agencies like the Gestapo. The Nazi regime’s decisive leadership and economic successes also meant that it remained popular with many Germans, some of whom were willing to denounce others for anti-Nazi behavior.

World War 2 in the Pacific

Japan signed the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy, thus entering the military alliance known as the "Axis." Faced with severe shortages of oil and other natural resources and driven by the ambition to displace the United States as the dominant Pacific power due to the economic sanctions imposed on Japan by the USA, Japan decided to attack the United States and British forces in Asia and seize the resources of Southeast Asia. In response to Japan’s attach of Pearl Harbour on 1 December 1941, the United States declared war on Japan. After the attack on Pearl Harbour, Japan achieved a long series of military successes, including the conquering of the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, Hong Kong, Malaya, Singapore, and Burma.

A Marine of the 1st Marine Division draws a bead on a Japanese sniper with his tommy-gun as his companion ducks for cover. The division is working to take Wana Ridge before the town of Shuri. Image source

A Marine of the 1st Marine Division draws a bead on a Japanese sniper with his tommy-gun as his companion ducks for cover. The division is working to take Wana Ridge before the town of Shuri. Image source

The turning point in the Pacific war came with the American naval victory in the Battle of Midway in June 1942. The Japanese fleet sustained heavy losses and was turned back. In August 1942, American forces attacked the Japanese in the Solomon Islands, forcing a costly withdrawal of Japanese forces from the island of Guadalcanal in February 1943. The Japanese, however, successfully defended their positions on the Chinese mainland until 1945. On August 6, 1945, the United States Air Force dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Tens of thousands of people died in the initial explosion, and many more died later from radiation exposure. Three days later, the United States dropped a bomb on the Japanese city of Nagasaki. Approximately 120,000 civilians died as a result of the two blasts. On August 8, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and invaded Japanese-occupied Manchuria. After Japan agreed to surrender on August 14, 1945, American forces began to occupy Japan. Japan formally surrendered to the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union on September 2, 1945.

Internment camps Image source

Internment camps Image source

Internment camps

Over 127,000 United States citizens were imprisoned during World War II for being of Japanese ancestry, Japanese Americans were suspected of remaining loyal to their ancestral land. Anti-Japanese paranoia increased because of a large Japanese presence on the West Coast. In the event of a Japanese invasion of the American mainland, Japanese Americans were feared as a security risk. Evacuation orders were posted in Japanese-American communities giving instructions on how to comply with the executive order. Many families sold their homes, their stores, and most of their assets. They could not be certain their homes and livelihoods would still be there upon their return. Because of the mad rush to sell, properties and inventories were often sold at a fraction of their true value.

Until the camps were completed, many of the evacuees were held in temporary centers, such as stables at local racetracks. Almost two-thirds of the interns were Nisei, or Japanese Americans born in the United States. It made no difference that many had never even been to Japan. Even Japanese-American veterans of World War I were forced to leave their homes.