Angola has a long and rich history, and is home to some of the largest historical kingdoms in Africa such as the Kingdom of Kongo or the Kingdom of Ndongo. The area which is now known as Angola was first inhabited at about 25 000 years BCE[i]. The name Angola comes from the word Ngola which was an iron object that symbolised kingship among the Mbundu and Lunda people[ii]. After 1 000 CE several larger centralised states began to form in different parts of present-day Angola.

The modern nation state of Angola came into existence after the Portuguese Empire colonised the various local people and created the colony of Angola. The colonial conquest of Angola by the Portuguese was a process which unfolded in various stages over almost 400 years. It began with the establishment of the colony of Luanda in 1575[iii] and ended when, in September 1915, the last king of the Kwanayamo, King Mandume, was defeated by the Portuguese, thus establishing Angola's contemporary borders[iv].

The anti-colonial struggle against the Portuguese intensified with the Angolan national revolution which started in 1961. Several factions fought against the Portuguese and Angola gained its independence on 11 November 1975[v]. Independence was followed by the 27 year long Angolan Civil War.

Early Inhabitants of Angola

Because of a reliance on oral history, and poor record keeping and little interest in their history by the Portuguese colonial authorities, there is much which is not known about the early inhabitants of Angola[vi]. The area which is now known be known as Angola was first inhabited in about 25 000 years BCE[vii]. The northern part of Angola which consists mostly of dense forest was settled by a people whose language and name has since been lost[viii]. More is known about the early inhabitants of the southern part of Angola. They were called the Khwe and were part of the Khoe language group[ix]. Research suggest that the Khwe developed as a distinctive language group about 2 000 years ago[x]. The Khwe people in southern Angola is estimated to have adopted a pastoralist mode of production somewhere between 1 000 BCE and 500 BCE[xi].

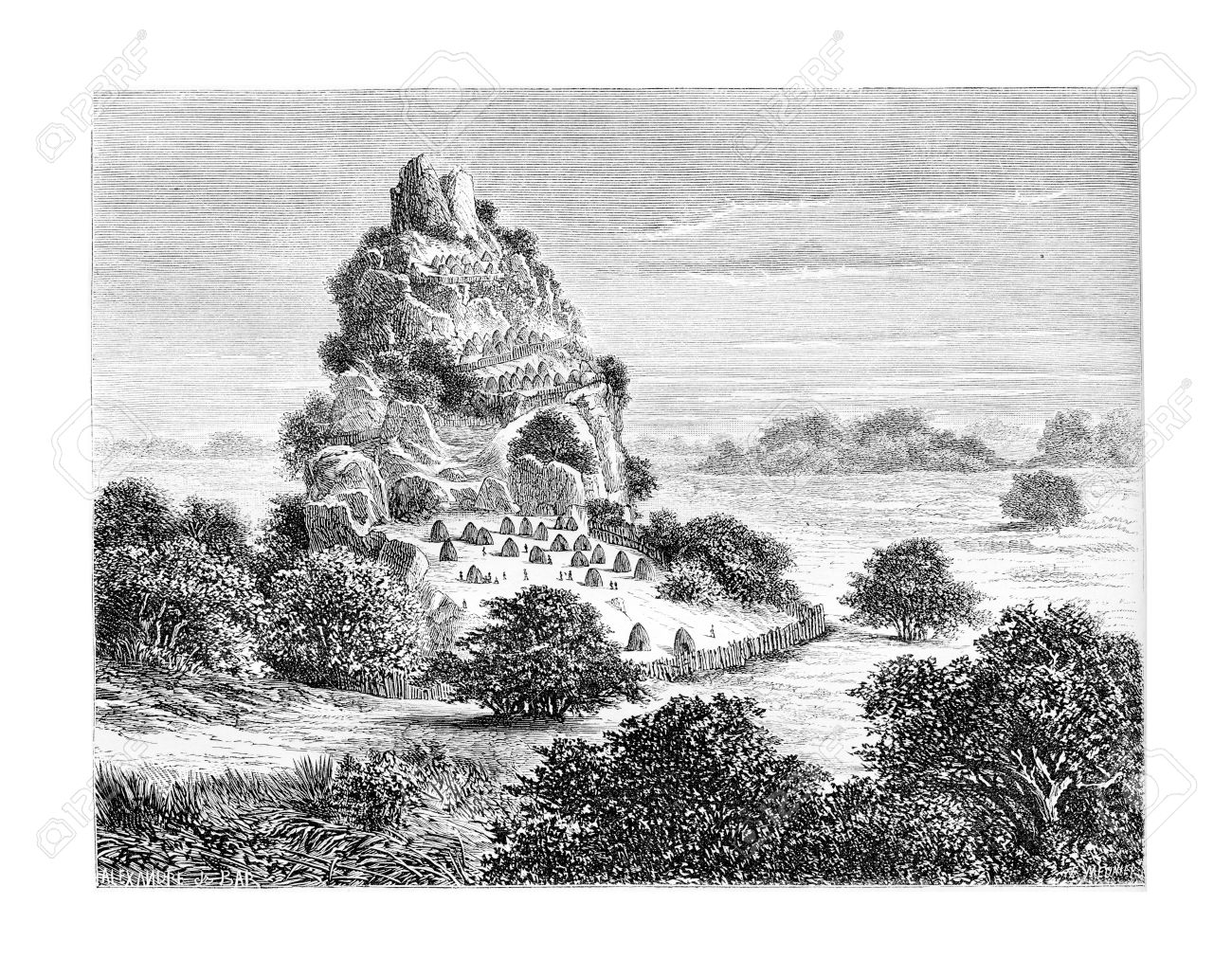

Near the town of Maquela do Zombo in northern Angola. Image source

Near the town of Maquela do Zombo in northern Angola. Image source

Sometime before 1000 CE Bantu speaking peoples migrated into the area from western-central Africa[xii]. It is widely believed that the origin of these migrations was somewhere around the present day Nigeria-Cameroonian border[xiii]. The Bantu speaking peoples brought with them technologies such as iron smelting and pottery-making[xiv]. The people of northern Angola become fully integrated in the Bantu-speaking communities so there is no remnant of their original language in present-day Angola[xv]. In southern Angola, the Khoe speaking peoples had some degree of isolation and many of the Khoe languages are still spoken today[xvi]. As the Bantu speaking peoples settled down they began to developed distinct linguistic communities. The largest of these were the Umbundu, Kimbundu, Kikongo, Chokwe, Kwanyama and Ngangela languege groups. The Khoe speaking and Bantu-speaking groups of people initially made alliances and intermarried, and they traded and shared technology. While they were on the move, the Bantu-speaking peoples herded mostly goats, and lived of hunting and gathering, but they began to herd cattle after trading with the Khwe people[xvii].

After 1000 CE several centralised states were formed by various Bantu speaking groups in northern and central Angola. Most notable of these were the Bakongo, Lunda and Mbundu[xviii]. It was during this time, especially amongst the Mbundu and Lunda peoples, that a system of lineage groups called Ngola arose[xix]. The Ngola was symbolised by an iron object which was controlled by each linage[xx]. The linage system Ngola was sometimes used as a royal title for kings in the area and would later become the inspiration for the name Angola[xxi]. The history of the various people which now populate Angola is diverse and in some instances does not interconnect until after the complete Portuguese colonial occupation in 1915 CE.

While larger centralised states were forming in northern Angola, the Ovimbundu (or southern Mbundu) were organised in several small kingdoms organised around kinship and locality. A variety of different political ideas and institutions were used to organise these different kingdoms[xxii]. Autocratic ideas of kingship existed together with semi-democratic tendencies creating ways in which the rulers and the ruled negotiated relations of power[xxiii]. There was a certain amount of centralisation of power, but it was always dependant on kings being perceptive of local issues. Through village councils, which were to some degree democratically elected, the kings ruled with much restraint imposed by ordinary people[xxiv].

The Kingdom of Kongo

The Kingdom of Kongo was probably the most famous and expansive of the kingdoms which formed in northern Angola. It was established by Bakongo speaking people and formed around the great city of Mbanza Kongo around 1390 CE[xxv]. The founding myth of the Kingdom of Kongo begins with the marriage of Nima a Nzima to Luqueni Luansanze, the daughter of Nsa-cu-Clau[xxvi]. Their marriage would cement the alliance between the Mpemba Kasi and the Mbata, an alliance which would become the foundation of the Kingdom of Kongo. Nima a Nzima and Luqueni Luansanze had a child, named Lukeni lua Nimi, who would be the first person to take the title Mutinù, which means King[xxvii]. Lukeni lua Nimi is presumed to have been born between 1367 and 1402 CE[xxviii]. Historians therefore also date the founding of the Kingdom of Kongo to be set sometime around 1390 CE. By 1490 the Kingdom of Kongo was estimated to in total have about 3 million subjects[xxix].

The first meeting between Portuguese explorers and King Nzinga a Nkuwu of the Kingdom of Kongo was in 1482[xxx]. Eight years later the King asked to be baptised and in the process changed his name to João I[xxxi]. The Christianisation of Kongo would cause many nobles to change their original names to Portuguese ones, and it would also entail the adoption of European named titles such as: Duke, Count and King. In 1506 there was conflict between King Afonso I and his brother. Afonso adopted Christianity, but his brother wanted to hold on to their traditional faith, there was an ensuing struggle in which Afonso and the Christians came out victorious[xxxii]. After this the Kingdom of Kongo was firmly established as a Catholic nation.

There was however a wide spread practice of mixing local beliefs and rituals with Catholic ones. For many people Catholicism was just one of many cults which were worshipped at the same time[xxxiii]. The reason why the Portuguese missionaries and clergy overlooked the continuation of local beliefs was that they had no choice. As opposed to the Americas, where large scale and total conversions happened, the Kingdom of Kongo was a strong kingdom and the missionaries were there only through the allowance of the King[xxxiv]. This meant that the missionaries had to much more diplomatic on how they treated local beliefs.

The export of slaves was a central to Kongo maintaining their relationship with Portugal[xxxv]. While slavery existed before the coming of the Portuguese it took on a much larger and brutal scale afterwards. The Portuguese began trading in slaves very early after their contact with the Kingdom of Kongo. The Kongolese King would however protect his all off his own subjects, called gente or freeborn Kongos, from slavery[xxxvi]. In the 1500s this was not a problem since the Kingdom of Kongo was experiencing a rapid expansion through various conquest, and therefore had a steady supply of foreign born slaves[xxxvii]. Most of the slaves came from wars waged against the neighbouring Mbundu kingdom of Ndongo around 1512[xxxviii]. While most slaves were exported to Portugal King Afonso of Kongo kept some slaves for himself. Both Afonso and later Kings would keep slaves, particularly enslaved criminals, but these slaves were freeborn Kongos and therefore they could not be sold to other parties[xxxix]. The trans-Atlantic slave trade, in particular that which involved the kidnapping and sale of freeborn Kongos, became a huge source of instability in the Kingdom[xl]. Despite this instability the Kingdom of Kongo managed to remain relatively stable for the next hundred years, but the Portuguese were constantly trying to assert their influence over the Kingdom which was exacerbated by the various incursions from, what is popularly referred to as, Jaga people from central Africa[xli]. Who or what the Jaga was is highly debated by historians. More recent studies conclude that the Jaga was a common name used by the Portuguese to name any smaller group who they did not know or understand, and who was opposed to their conquest[xlii].

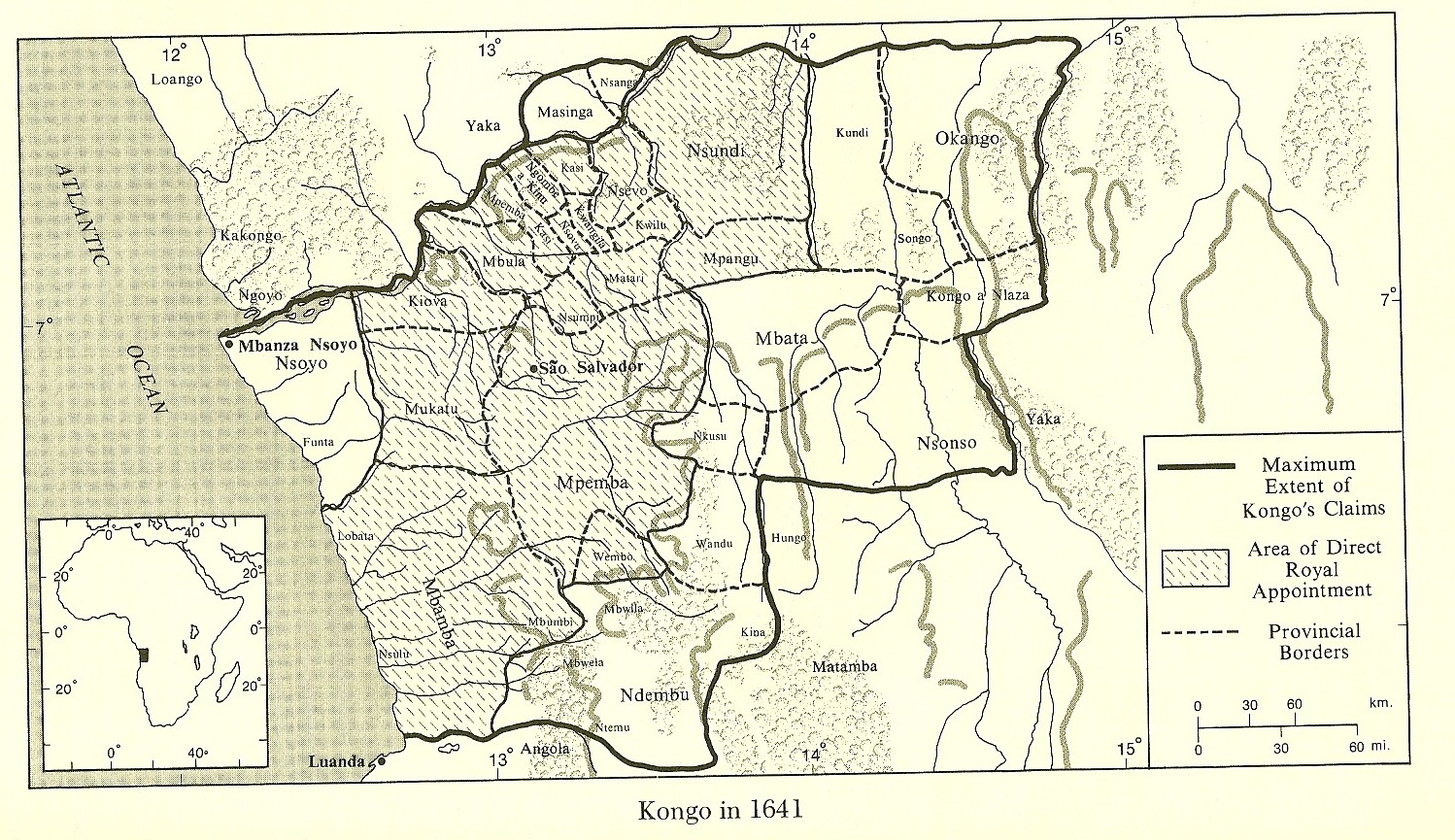

The Kingdom of Kongo in 1641. Image source

The Kingdom of Kongo in 1641. Image source

Before 1641 the Kingdom of Kongo had managed to fight of several Portuguese incursions and had remained a strong and centralised state. After 1641 this would all change. Sonyo was one of the richest provinces in the Kingdom of Kongo[xliii] , the province was also home to the Counts of Soyo. In 1593 there was a civil war between Kongo and Soyo[xliv] , so this province had been a source of internal conflict before. In 1641 the Soyo declared independence under Count Daniel da Silva, and King Garcia II of Kongo declared war against the rebels[xlv]. Meanwhile in 1665 the Portuguese invaded the Kingdom of Kongo and the two states fought each other in the Battle of Mvwila[xlvi]. The Kongolese forces lost and King António I of Kongo was killed by the Portuguese soldiers[xlvii]. The Portuguese also seized the island of Luanda, an important source of the local currency: Nzimbu shells[xlviii].

King António I died without a son and this left Kongo with no clear line of succession. Two feuding branches of the royal family would battle for the kingdom after this. The Kimpanzu faction and the Kinlaza faction divided much of the country between them and would struggle for their side of the family to control the kingship over the next hundred years[xlix]. The civil war between Soyo and Kongo raged on at the same time, and both sides attempted to get European powers; Holland, Brazil and Portugal, to back their side. In 1670, and despite having fought each other five years earlier, a joint Portuguese and Kongolese force invaded Soyo and were in turn soundly defeated by the Soyo forces[l]. The Soyo manipulated and exacerbated this conflict between the Kimpanzu and the Kinlaza as well, so that they could create further instability in the Kingdom of kongo[li].

There is much debate between academics and historians of why the Kingdom of Kongo came apart so rapidly in the mid-1600s. The pressures of the slave trade and its constant demand for fresh slaves de-legitimised the power of the king[lii]. Portuguese military expeditions against the Kingdom certainly was a factor in creating instability, and through the death of King António I directly sparked the civil war[liii]. The third, and some argue, the greatest reason for the decline of the Kingdom of Kongo was the conflict between the Counts of Soyo and the Kings of Kongo[liv].

The Kingdom of Kongo was from the 1700s a decentralised Kingdom and largely dependent on slave labour and armies[lv]. This century saw the emergence of clans as an important political player, especially because the clans would come together and elect the Kings. As part of the peace agreement between the two warring factions King Manuel II, of the Kimpanzu faction, would be crowned king in 1718[lvi]. The area he would rule over would only cover São Salvador (previously named (Mbanza Kongo) and Kimbangu. After his death in 1743 a member of the Kinlaza faction took over, named King Garcia IV[lvii]. During Garcia IV's reign São Salvador was again recognised as the capital of the entire Kingdom[lviii].

The power struggle between various factions over who was going to rule, continued into the 1800s, further eroding the legitimacy and power of the King[lix]. In 1842 Henrique II, representing a new faction called the Kivuzi, was crowned King[lx]. The new faction would be short lived, and disputes about who was going to rule continued. One of the greatest changes of the 1800s was however not political, but rather of an economic nature. By 1839 the British had abolished the slave trade, and was patrolling the shores of Kongo making sure that no ships would transport slaves across the Atlantic[lxi]. This meant that the main source of foreign revenue the Kingdom had was drying up. A trade in ivory and rubber were becoming a dominant part of the economy during this time[lxii].

The rubber trade in particular was not dependant on large armies and centralised power as the slave trade had been. What was essential for the rubber trade was a small and mobile workforce[lxiii]. Since the rubber grew inland large parts of the population moved inland to harvest and sell it to European traders. The larger population dense villages and cities, which had been the main source of power for the Kongo nobility and royalty, disappeared[lxiv]. Mobility had always been an essential part of Kongolese society, and people could pack down entire houses and move on short notice[lxv]. By 1880 most of the Kingdom of Kongo was now made up of small decentralised trading villages[lxvi].

During the Berlin Conference of 1884 – 1885 the European powers decided that Portugal would take most of what remained of the Kingdom of Kongo, and Belgium would take the rest. For Portugal to claim their part they had to occupy it as well however[lxvii]. Portugal had limited military success against the Kingdom of Kongo in the past, and they need an alternative route to conquest. An opportunity for occupation arose in 1883, when King Pedro V, of the Kingdom of Kongo, was fighting a rival faction lead by Alvaro XIII[lxviii].

Pedro V invited the Portuguese into an alliance to fight Alvaro XIII, in return Portugal would station soldiers in São Salvador[lxix]. This was a great mistake as it allowed the Portuguese to effectively take control of the capital city. In 1888 the Portuguese forces defeated Alvaro XIII and occupied São Salvador, they made King Pedro V a vassal and demanded rights to collect taxes and trade revenues[lxx]. This effectively ended the independence of the Kingdom of Kongo, and by the early 1900s the Kingdom was integrated into the Portuguese colony of Angola[lxxi].

The Mbundu Kingdom of Ndongo

At its height the Kingdom of Ndongo was one of the largest states in central Africa, although it was smaller than the neighbouring Kingdom of Kongo[lxxii]. The Ndongo Kingdom was established by the Mbundu people who occupied large areas of present day Angola. The Kingdom was ruled by the Ngola, which acted as a monarch and ruling figurehead. It is from the Ngola title that the contemporary state of Angola would derive its name[lxxiii]. The Kingdom started out as a vassal state to the Kingdom of Kongo, but broke free in the early 1500s. The Ngola who ruled the Kingdom of Ndongo would be appointed after an election process where in which various members of the ruling dynasty was considered to be next king[lxxiv]. From 1520 the Kingdom of Kongo and the Kingdom of Ndongo was embroiled in a series of conflicts[lxxv].

The Ngola, who ruled the Kingdom of Ngongo, sent an envoy to establish an embassy in Portugal in 1548[lxxvi]. The envoy would, however, only reach Lisbon in 1557[lxxvii]. It is speculated that Ngola was seeking further help from the Portuguese to protect his Kingdom from invading Imbangala forces from the east[lxxviii]. In 1560 the Portuguese sent an official mission to the Kingdom of Ndongo[lxxix]. Yet the Portuguese was helping the Kingdom of Ndongo as early as 1526, as King Afonso I of the Kingdom of Kongo, complained about this assistance in a letter to the King of Portugal sent in 1526[lxxx]. The conflicts which followed would lead to a large amount of people in both kingdoms being captured, enslaved and sold to the Portuguese, by the opposing party (and sometimes sold by their own families who had been impoverished by the war). The conflict between Ndongo and Kongo was fuelled by the importance which the slave trade had in both nations’ economies[lxxxi]. Similarly to Kongo the slave trade would eventually destabilise the Kingdom of Ndongo and corrode the legitimacy of the Ngolas.

After the 1560s, and with the end of their war with Kongo, the Kingdom of Ndongo came into greater interaction with the Portuguese Empire. In the period between 1560 and 1579 Portugal sent several missionaries to the Ndongo in attempts to set up a Catholic church in the Kingdom. In 1575 the Portuguese set up its first modern colony on what would later become the colony of Angola[lxxxii]. The first outpost was set up on the island of Luanda and it would be a starting point for a long lasting conflict between the Ndongo and the Portuguese. From 1575 to 1663 Portugal was in constant war with the Kingdom of Ndongo in an effort to conquer more land and acquire slaves[lxxxiii]. It was in this period that Queen Njinga Mbandi Ana de Sousa of Ndongo, the most famous monarch in the history of the Kingdom ruled.

Njinga was the brother of Ngola Mbandi who ruled the Kingdom of Ndongo in the 1620s. In 1622 she and her brother travelled to Luanda to negotiate a peace treaty with the Portuguese living there[lxxxiv]. Njinga would stay with Portuguese for several months and was eventually baptised Ana de Sousa by the local missionaries. In 1624 her brother died and Njinga was elected queen of the Ndongo by the eligible electors in the royal court[lxxxv]. Queen Njinga's rivals within the royal court joined with the Portuguese and attempted to take power in the Kingdom of Ndongo. In an effort to fight her enemies she looked from one of the many Imbangala warrior bands who was roaming the area at the time. She became the head of one of the band and between 1626 and 1655 she personally led many of the following battles against the Portuguese[lxxxvi].

In 1641 war was raging between the Dutch and the Portueguese and both the Kingdoms of Kongo and Ndongo allied with the Dutch in an effort to drive out the Portuguese from Angola. The alliance almost managed to drive the Portuguese completely out of Central Africa. The Dutch conquered Luanda and blocked most of the Portuguese outposts and colonies on the African coast. It was only by the aid of Brazil and an armada of ships led by Salvador de Sá in 1648 that the Portuguese colonies Africa were saved[lxxxvii]. The Dutch capitulated and Queen Njinga fled to the state of Matamba and continued her resistance against the Portuguese from there. By 1655 Njinga had been in constant war and battles for more than 25 years. Most of her life had been dedicated to fighting the Portuguese invaders.

Italian illustrations from 1732. Image source

Italian illustrations from 1732. Image source

From 1655 to 1663 she negotiated a peace treaty with the Portuguese through a series of letter exchanges[lxxxviii]. Ndongo captives, including Njinga's sister, where returned from the Portuguese. In return Njinga returned to the Catholic Church, gave up her many male consorts, and got married in a Catholic ceremony[lxxxix]. It was during the life of Njinga that the Colony of Angola became a major hub for the trans-Atlantic slave trade. It was in essence this expansion of the slave trade and against Portuguese slave raiders which she fought. Although after the war Queen Njinga also engaged in the slave trade and sold captured people to the Portuguese[xc]. Queen Njinga died of natural causes in 1663.

In 1671 the Portuguese would again go to war against the Kingdom of Ndongo. On November 29, 1671, the Portuguese forces captured the fortress of Pungu-a-Ndongo effectively ending the territorial integrity of the Kingdom of Ndongo and beginning its integration into the Colony of Angola[xci].

The Lunda States

In the late 1500s and early 1600s the Lunda people, also known as the Imbangala, came to Angola as refugees fleeing from the expanding Luba of Katanga[xcii]. Stories from Angola tells that the refugees was led by a man named Kinguri-kya-Bangela. The refugees organised the Lunda state, or what is also known as the Imbangala Kingdom, and then began to expand their influence[xciii]. Several expedition forces left the Lunda capital and went out to set up new villages and settlements in the north-eastern part of present-day-Angola. In this sense the Lunda state was in actuality a series of smaller states and kingdoms with different leadership who occasionally worked together. These separate states and kingdoms were connected by a tribute and exchange sphere, and could be described as a commonwealth[xciv].

The most famous of the Lunda states was the Kingdom of Kasanje which was founded either in 1614[xcv] or in 1635[xcvi]. The Lunda chief, Kasanje-Ka-Kulashingo, and the group he led was first absorbed into a Jaga band and then they conquered land belonging to the Pende. After this the Kasanje engaged in several battles with the Ndongo Kingdom. As stated above the Ndongo Kingdom was the largest of the Mbundu polities. After allying with several dissatisfied Mbundu chiefs, Kasanje defeated the Mbundu, and established the Kasanje Kingdom[xcvii]. He then met the Portuguese colonists who had settle on the island called Luanda[xcviii]. Kasanje treated with the Portuguese and in exchange for various gifts he invited them to settle on the mainland of Angola. He rejected the Portuguese offer of becoming a subject to the Kingdom of Portugal however[xcix]. The Kasanje Kingdom reached its hight in the 1700s. It was then a prosperous kingdom and a centre of trade[c]. The Kasanje Kingdom would remain strong until the 1800s when it was slowly corroded by the increasing slave trade and a general decentralisation of power[ci].

Another powerful Lunda polity emerged in central Angola during the early 1700s. After the Gando state, in the central highlands of Angola, was occupied by the Portuguese in 1685, the original rulers of the state allied with Lunda forces[cii]. Together the new coalition swore to drive the Portuguese into the sea, and in 1718 they attacked the Portuguese fort in Caconda[ciii]. They never managed to take back the fortress, but the coalition halted all Portuguese advances in the area[civ]. The coalition then set up several states which remained independent in peaceful times, but who exchanged military support, weapons and tribute in times of war[cv].

The Lunda states began their decline in by the early 1800s. The slave trade was decimating local populations and caused internal conflict. The states had also relied on much of their power as a dominant trading power in the area, and various Lunda states had often mediated trade between European and African states[cvi]. This dominant position of trade was by the 1850s taken over by other more recently formed political formations in the area. The abolition of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and the rise of trade in rubber and ivory would also reduce the power of more centralised and densely populated states. In addition to this the Lunda states experienced an influx of migrants from the north, called the Chokwe[cvii]. Using gunpowder based weapons, and by utilising internal conflicts in the Lunda states, the Chokwe subjugated most of the Lunda states in Angola. By 1900 the Chokwe dominated all the areas in Angola which had previously been controlled by various Lunda states.

The Ovimbundu Kingdoms

By the 1800s the Ovimbundu people had settled in the central highlands of Angola and formed about 22 different kingdoms who had various degrees of autonomy and cooperation with each other[cviii]. This was then, and remains now, one of the most densely populated areas Angola. The subjects of the Ovimbundu kingdoms shared a common language as they were all Umbundu speakers.

Cingolo, an Ovimbundu kingdom. Illustration made in 1881. Image source

Cingolo, an Ovimbundu kingdom. Illustration made in 1881. Image source

The Ovimbundu Kingdoms had, by 1840, commercial ties with many of the other peoples living in Angola, as well as the Portuguese colony in the western part of the country[cix]. It was with the help of the Portuguese that many of the Ovimbundu kings had managed to seize power sometimes in the 1700s. This created a special bond between the Ovimbundu and the Portuguese. The Portuguese were reluctant to invade the Ovimbundu as they more of a commercial and political interest in keeping them independent[cx].

Several of the Ovimbundu kings were engaged in slave raids and provided much of the slaves who were sold to the Portuguese. This cooperation with the Portuguese aided the Ovimbundu in keeping political autonomy for much longer than most of their neighbouring peoples[cxi]. It should be mentioned as well that the Portuguese were also hesitant of conquering to far inland in Central Africa. Up until the 1870s there was a strict policy amongst the Portuguese colonialists of “no more than 50 to 100 leagues from the coast”[cxii]. So while northern neighbours such as the Ndongo were being incorporated into the Colony of Angola, the Ovimbundu retained a large degree of political autonomy.

The end of the trans-Atlantic slave trade in the 1830s and 40s would be disastrous for the Ovimbundu political elite[cxiii]. The elites had made themselves a necessity when the slave trade became such a dominant part of the economy. To capture slaves one needed large and organised raiding parties. These larger armed forced could mostly be organised and maintained by more centralised state institutions. This meant that the kings and the nobility held a tight control of the most important commercial and economic activity in the Kingdoms. With the end of the slave trade their control and power waned. This was also the case in other Kingdoms in the area such as the Kingdom of Kongo.

The Ovimbundu now also owned hundreds of thousands of slaves which were of non-Ovimbundu origins. They would normally had been sold to the Portuguese, but now they had to be integrated into Ovimbundu society. This sudden influx of such a large amount of freed slaves caused a mass disruption of the existing social structures. This erosion of the central authority of the kings and Portugal no longer needing the Ovimbundu for the slave trade, made them very vulnerable to colonial occupation[cxiv]. Between 1890 and 1904 the Portuguese conquered all of the Ovimbundu kingdoms and incorporated them into the Colony of Angola.

The Portuguese Colony of Angola

The colonial conquest of Angola by the Portuguese was a process which unfolded in various stages over almost 400 years. It began with the missionaries in the Kingdom of Kongo in the 1490s and the establishment of colony of Luanda in 1575. In the beginning the Portuguese were mostly interested in slave trade. They conquered the coastal areas which could serve as slave trading hubs. Luanda was the biggest of these, but another large colonial hub was the city of Benguela which was established in 1617[cxv]. The Portuguese would then either do slaving raids into the country from these coastal fortresses or rely on local inland rulers to sell them slaves who had been captured during local conflicts. At most Portuguese colonial settlements in inland Angola was limited to trade posts and missionary stations.

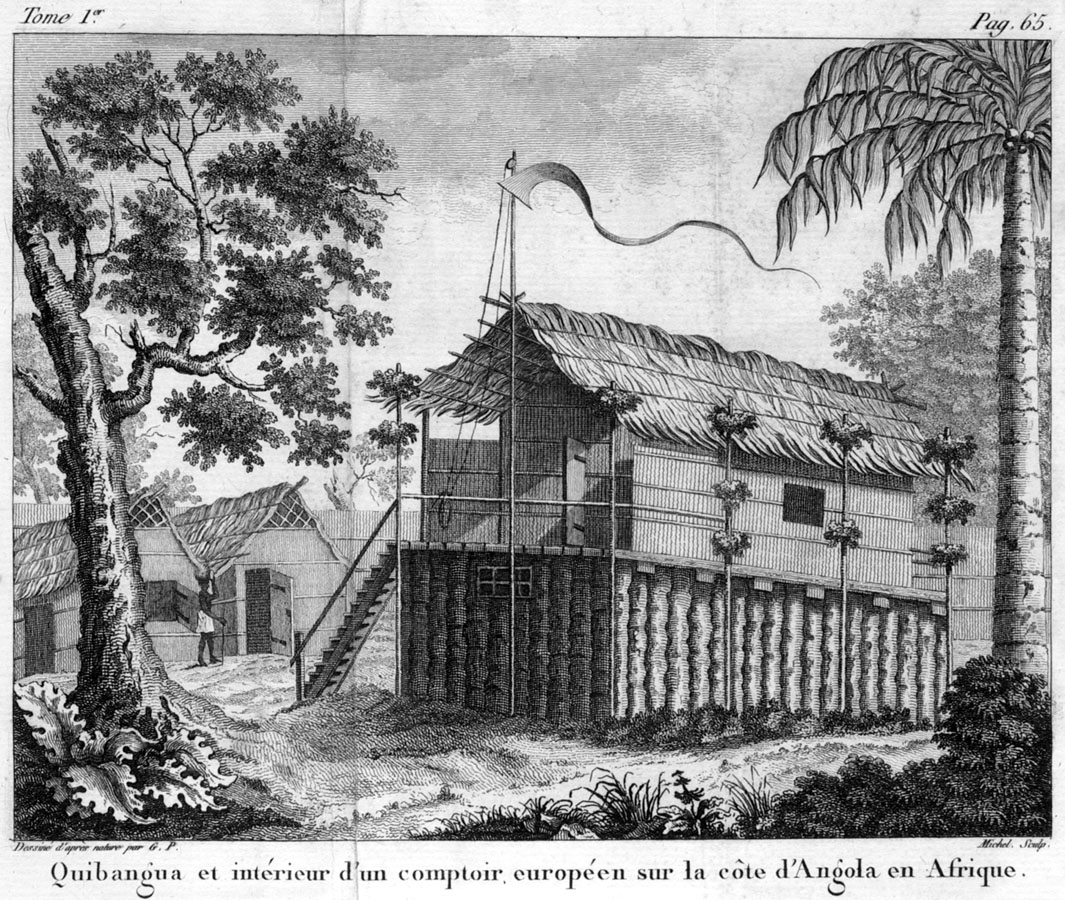

A European trade post in Angola. Image source

A European trade post in Angola. Image source

The slave trade was a source of enrichment for some of the local nobility, but it would eventually lead to the destabilisation and demise of some of the largest Kingdoms in pre-colonial Angola[cxvi]. For those kingdoms, like the Ovimbundu, who prospered from the slave trade the abolition of the trade in 1836 would create internal turmoil and make them vulnerable to conquest. From 1500 to 1900 the Portuguese was in almost constant conflict with one of the many peoples who inhabited Angola at the time. Some, like the Kingdom of Kongo or the Kingdom of Ndongo, resisted for centuries[cxvii].

The Ndongo was conquered and integrated into the colony in 1671, and the Kingdom of Kongo would lose all remaining autonomy in the early 1900s. The Ovimbundu Kingdoms were all integrated into the Colony of Angola by 1904. The last people to be subjugated was Kwanyamo, a subset of the Ovambo peoples, in Southern Angola. In September 1915 the last king of the Kwanayamo, King Mandume, was defeated by the Portuguese[cxviii]. The defeat of the Kwanyamo marked the total domination by the Portuguese over Angola, and at this point the Colony reached the boundaries which had been stipulated in the Berlin Conference of 1884 – 1885 by the European colonial powers. None of the people of Angola was present or had any say at the conference, and the boundaries which were set would cut through already existing social formations. The Kwanyamo people, for example, was split between German South West Africa (now Namibia) and Portuguese Angola. The Kingdom of Kongo, which had been one of the largest kingdoms in Africa, was split between Belgium and Portugal.

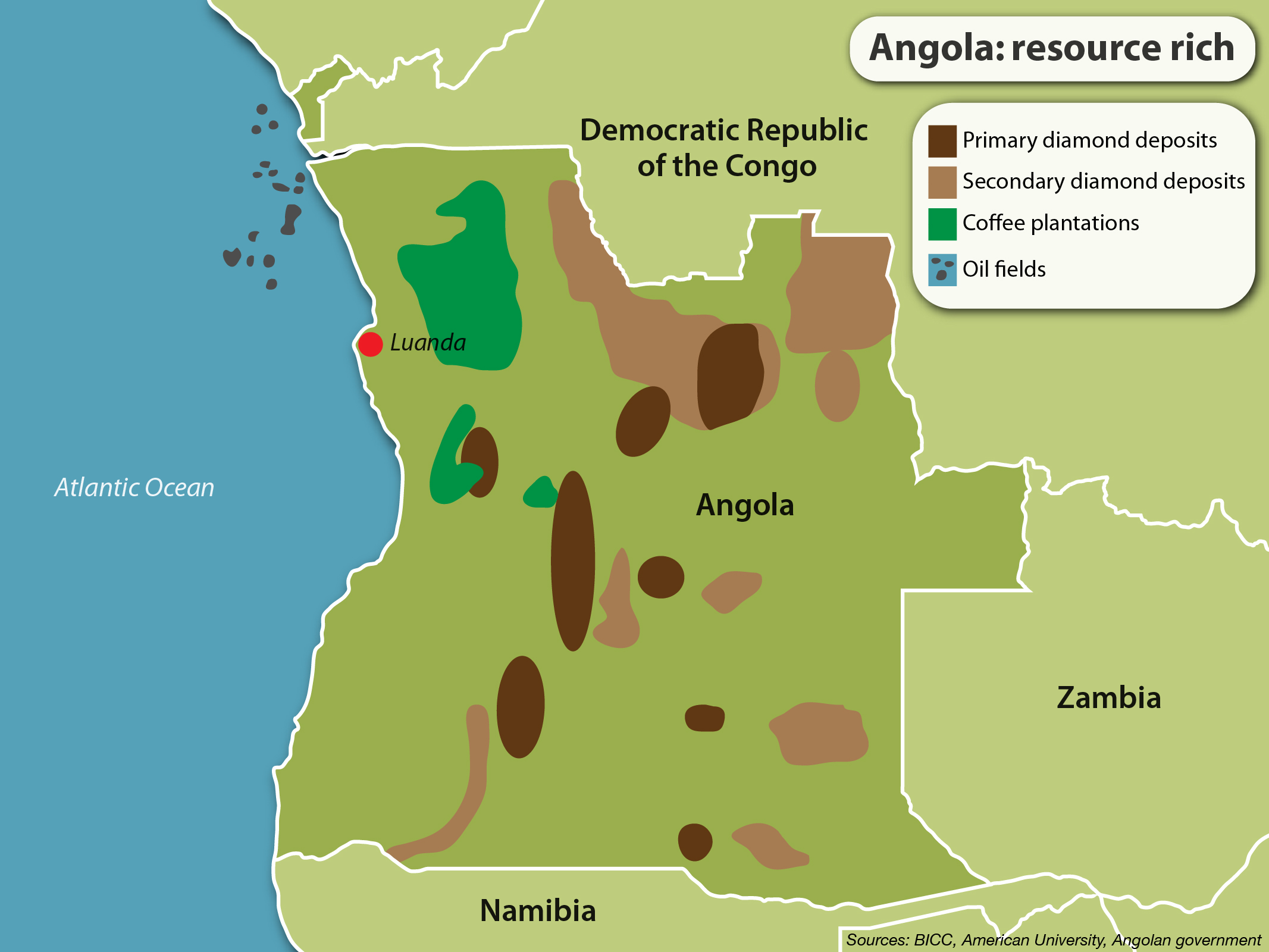

In 1890 the British Empire halted any attempts by the Portuguese to expand Angola any further east[cxix]. By the mid-1920s the Angolan colony had about the same borders as the modern nation state. In 1926 the southern border shared with South West Africa (which officially came under the control of South Africa in 1919) was negotiated with South Africa, settling the last of the border disputes with other European colonial powers[cxx]. It was the lure of commercial farming (cocoa and sugar cane), diamonds, and rubber, which had made the Portuguese want to expand their colony from the coast to further inland. Once the actual mineral resources were firmly under Portuguese control the colonial administration now needed workers to extract those minerals. This labour would come at a huge cost to the local Angolan people.

Life was hard for the majority of African people living in the colony. While the trans-Atlantic slave trade was made illegal in 1836 it was still legal to own slaves in Angola until 1875[cxxi][cxxii]. In many places various forms of slavery would continue long into the 1900s. It was not uncommon for Angolans to be transported against their will to plantations in the French colonies in the Caribbean or to the cocoa plantations on the island of São Tomé up until 1910[cxxiii].

Various forms of slavery and forced labour was common into the mid-1900s. The colonial authorities would regularly round up Angolans and through violence and intimidation conscript them into work regiments for various colonial projects[cxxiv]. For the people recruited into forced labour life was hard and short. Plantations rarely paid any remunerations, and when they did it was inconsistent, minimal and sometimes only usable at the local plantation shop. Workers were regularly whipped and beaten, sometimes to death, and the situation for local Angolans was so bad that one journalist named it an “economy of terror”[cxxv]. An Angolan man, named Salomo Paipo, was recruited by a colonial administrator to work on a plantation on São Tomé, and he recounts a story of a fellow worker who was beaten so severely by the bosses that he committed suicide by hanging himself afterwards[cxxvi]. Angry at a worker for his suicide the bosses of the plantation denied him a dignified funeral and instead burnt the body on the local highway[cxxvii].

The similarities between the slavery of the previous centuries and the labour system of the late 1800s and early 1900s were uncanny. In 1908 a chocolate producer, William Cadbury, walked up a labour recruitment trail and found wooden shackles all over the sides of the road. People coerced into forced labour would have their shackles removed only the moment they signed their labour contracts and then they would be sent off to their designated place of work[cxxviii]. It was usual for colonial administrators to go to inland villages and recruit mostly young men to various work on plantations and colonial projects. The young men would sign contracts which were meant to be for between two and five years, but in most places they were automatically renewed upon expiration. This meant that very few of the people recruited from the various inland villages would ever return home again[cxxix].

The British, who had for centuries had a special relationship with Portugal, made arrangements for Angolan and Mozambican people to be sent to work in their gold and diamond mines in the Transvaal or in the Cape Colony[cxxx]. This relationship between British and Portuguese colonies created the foundations for a migrant labour system which would encompass most of Southern Africa up until the after the 1990s. Up until the 1960s Angolan people was coerced into travelling to South Africa to work in the mines there[cxxxi].

For European settlers the Angolan colony was enticing place to move as it offered opportunities denied in Europe. In 1912 there was an attempt at establishing a Jewish homeland in Angola, and while it failed, Angola would draw a reasonable amount of Jewish settlers as an effect of the persecution of Jews in Portugal since the 1500s. By 1920 there were about 20.000 Europeans living in Angola[cxxxii]. In the 1920s there was a great influx of Boer settlers from South Africa, but large scale settlement was held back by the lack of arable land in Angola[cxxxiii]. Local Angolans also fought fiercely against attempts at setting up farms. In 1904, 1907 and 1917 attempts at setting up plantations close to the town of Porto Amboim was ended by local uprisings. The farms were burnt and the settlers were killed or driven out of the area. The Portuguese army would then come in and protect settlers as they rebuilt the plantations[cxxxiv].

In 1926 there was a military coup in Portugal which would eventually lead to António de Oliveira Salazar gaining “supreme power” of the country. Salazar greatly cut spending to the colony and emphasised that for Angola to be profitable the colonial economy had to rely even more on “cheap African labour”[cxxxv]. The white population of Angola was not to work in the farm, but should become managers and shop keepers. This meant that the poor and uneducated in Portugal could rise fast in status and economic prosperity by moving to the colony. After 1926 Angola began to create legislation which advocated strict segregation between the European and African people. That year the “Native statute, was introduced and it defined all people living in Angola as either “citizen” or “native”[cxxxvi]. People categorised as “native” had to pay a poll tax (previously called hut tax), was liable to be conscripted into forced labour, and also had to carry a pass book at all times. To become a citizen a person had to prove to the colonial authorities that they were monogamous, spoke fluent Portuguese, ate with a knife and fork, and wore European clothes[cxxxvii].

In reality the Native Statute of 1926 was used as a gate keeping tool to regulate who could access economic and social opportunities. In the early 1900s the idea, imported from Victorian Britain, that based on skin colour some people are inherently better than others became prominent in the colony. This divided people into the racial categories of black or white. After this time a black and white racial divide would increasingly become the proxy for whom was allowed to gain citizenship and the privileges that went with it. In Luanda there was a class of black Angolans who had gained a European education and had lived in the colony and mixed with European people for generations. They had experienced a limited amount of privilege compared to other black Angolans, but they were in the early 1900s increasingly marginalised because of the introduction of an oppressive ideology based on race[cxxxviii].

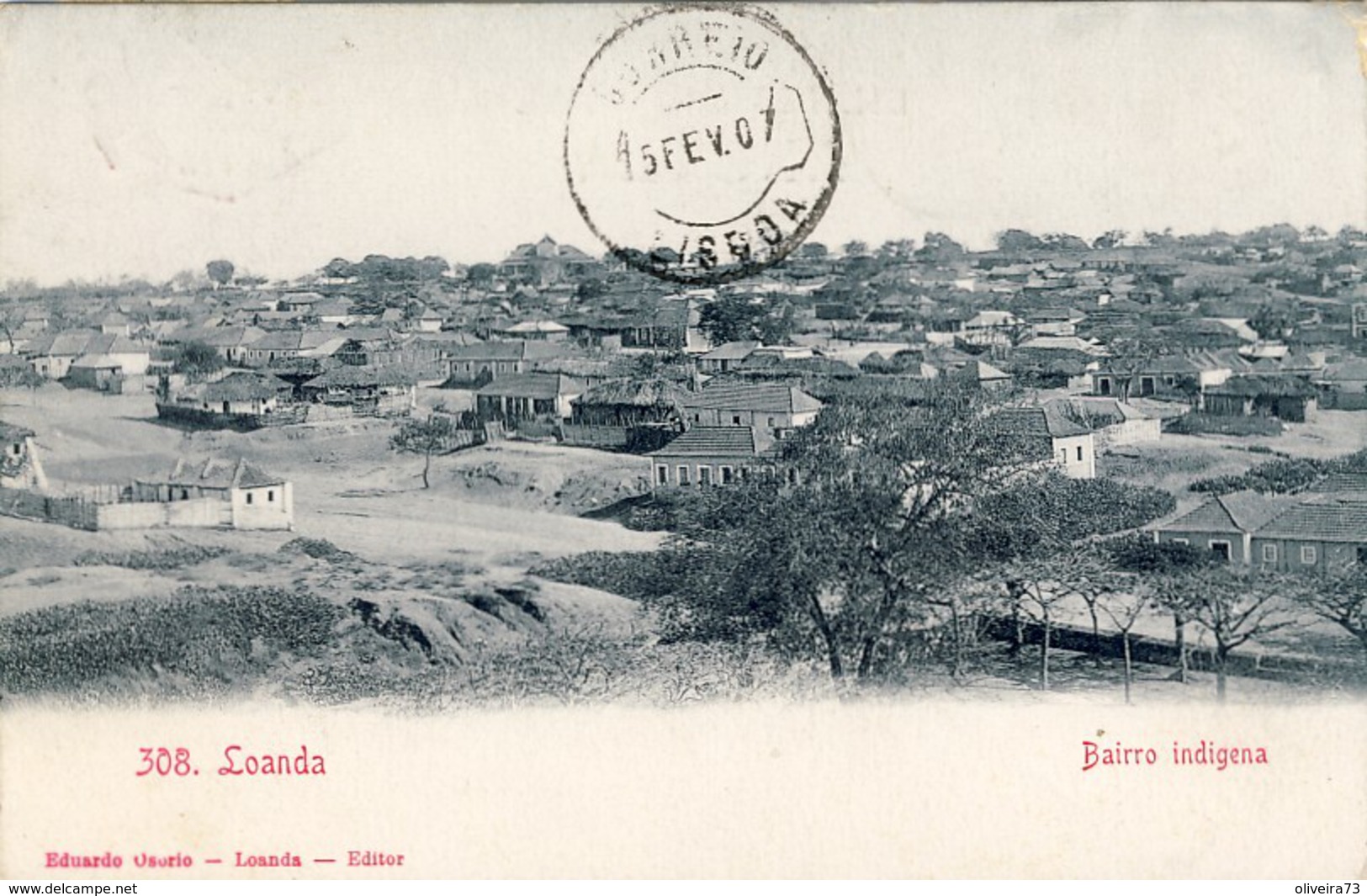

Postcard of Luanda from the 1920s. Image source

Postcard of Luanda from the 1920s. Image source

After World War II in 1945 there was a great demand for coffee in the world, and in the next 30 years Angola's coffee industry would expand producing 200.000 tons of coffee a year in 1975[cxxxix]. Most of the coffee was produced on larger plantations owned by white settlers, but in northern Angola there were still coffee grown on small plots of land owned by African peasants. Yet the settlers would control storage, transport and the export part of the supply chain, including shops where people could buy household goods. The black peasants would use their future crops to buy everyday needs, and when there was a credit crisis or failure in the crops the shop-keepers would take ownership of the land which had been used as collateral[cxl]. The plantations therefore slowly spread north and the peasants became labourers on land which they had previously owned. Plantations also meant an increased need for labour which the plantation owners mitigated by bringing in workers from south-central Angola, where the Ovimbundu people lived. The Bakongo northerners were upset with the newcomers as they had lost their land, and the southern Ovimbundu were angry about being forced into labour and moved away from their families. This anger led to the forming of the Union of the People of Angola (UPA) and a mass uprising in the north in March 1961[cxli].

Things were not good in the rest of Angola either. In 1954 an estimated 300.000 people still lived in what can only be described as slavery (although not named as such)[cxlii]. On February 4, 1961, a large group of Angolan people stormed several prisons in Luanda. It is debated between historians whether the rebellion was a spontaneous uprising or directed by the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA)[cxliii]. The uprisings in Luanda and in the north became the starting point for the Angolan national revolution to free themselves from Portuguese rule[cxliv]. MPLA which was Marxist in ideology had been founded by an amalgamation of several smaller parties in 1956. The party was rooted in urban areas and particularly strong in Luanda. They wanted a socialist revolution as well as independence from Portugal, and in 1962 Agostinho Neto was elected president of the party[cxlv]. The UPA wanted to restore the Kingdom of Kongo to what it was in its glory days, and the party leader was called Holden Roberto[cxlvi]. In 1962 Roberto renamed the party National Front for the Liberation of Angola (FNLA), and made it a party for the freedom of all Angolan people.

The Angolan National Revolution

The northern uprising in March 1961 by the UPA (later to become the FNLA), and the storming of the prisons in Luanda by the MPLA in February that same year, marked the beginning of the Angolan National Revolution[cxlvii]. The uprising in the north was by far the most lethal as an estimated 40.000 Africans and 400 Europeans was killed, some in the uprising and others by the Portuguese retaliations[cxlviii]. In Januray, 1961, the Portuguese forces sent airplanes to bomb several villages involved in a strike in the cotton industry in northern Angola. The bombings is estimated to have destroyed 17 villages and killed about 20.000 people[cxlix]. The leader of the FNLA, Holden Roberto, established a government in exile in an attempt at making his party the legitimate representatives of the Angolan liberation struggle. Angola's Revolutionary Government in Exile (GRAE) was based in Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Jonas Savimbi was one of the prominent ministers in the government. By 1964 the FNLA had set up a camp in exile in Congo-Léopoldville (now Kinshasa) and the MPLA had set up their headquarters across the river in Congo-Brazzaville[cl].

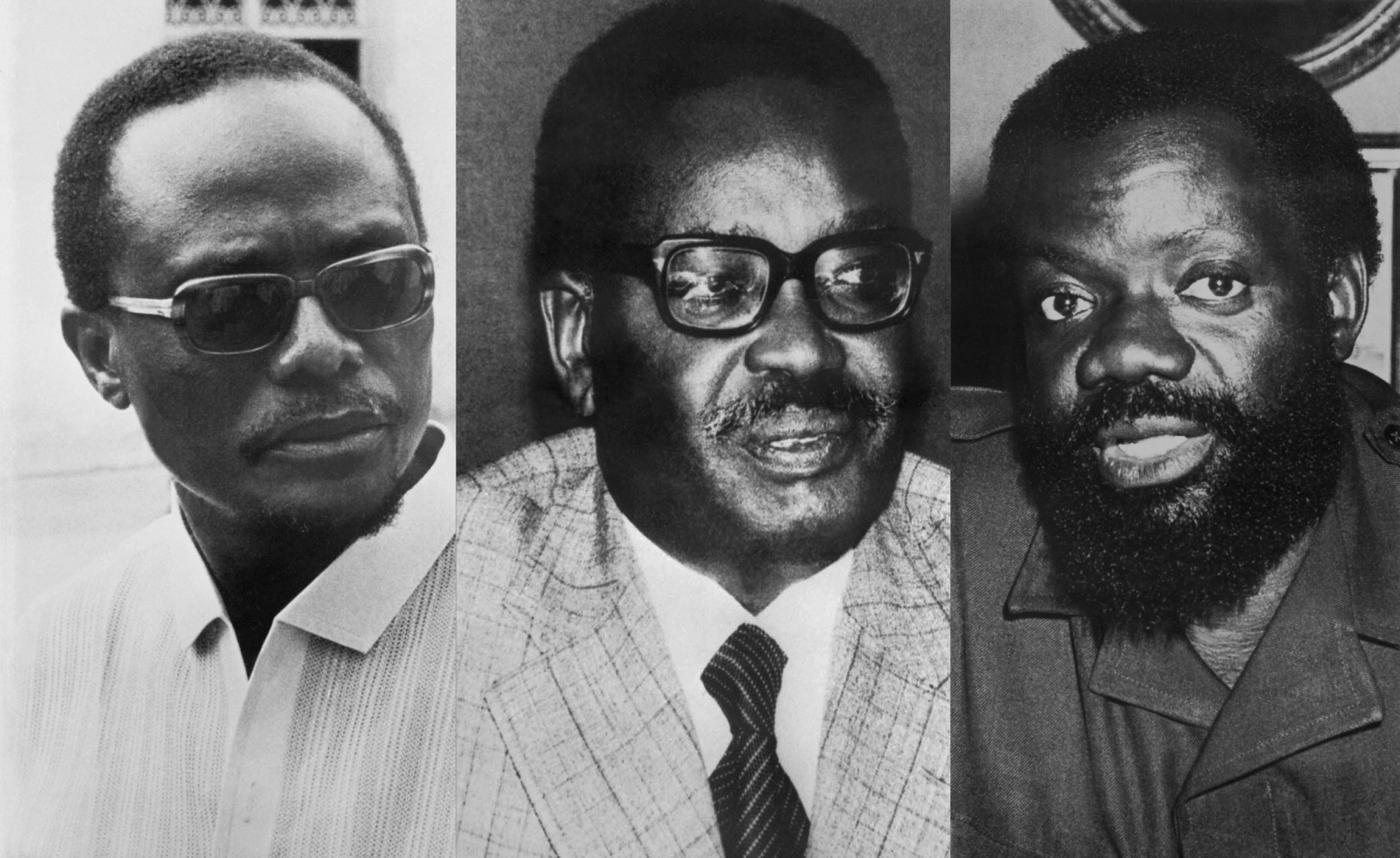

Holden Roberto (FNLA), Agostinho Neto (MPLA) and Jonas Savimbi (UNITA), the leaders of the major factions struggling for Angolan independence. Image source

Holden Roberto (FNLA), Agostinho Neto (MPLA) and Jonas Savimbi (UNITA), the leaders of the major factions struggling for Angolan independence. Image source

Jonas Savimbi would break with the FNLA in 1964, over disagreements with Roberto, and would in 1966 be the head of another political party called National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA)[cli]. Savimbi argued that the FNLA was too focused on the northern Bakongo speaking peoples and the MPLA was not African enough, as much of the leaders came from the Luandan mestizo community. UNITA launched itself as a party for the African peasants of Angola, yet it remained a very small force over the course of the independence struggle and would draw its support mainly from Ovimbundu peoples. UNITA, FNLA and MPLA would be the three dominated forces fighting for the national liberation of Angola. By 1968 the MPLA had established itself internationally as the primary force of the national revolution for independence[clii].

To limit further uprisings and rebellions Portugal began making investments in infrastructure, building schools, and assist struggling farmers. They also sent an additional 40.000 Portuguese soldiers to maintain the peace and oppress any acts of rebellion[cliii]. The Angolan struggle for liberation was met with severe retaliation from the Portuguese government. Chemical attacks and napalm to scorch forests away was used to suppress guerrilla tactics, and about 1 million people were forced to resettle into “protected villages”[cliv]. This would make it difficult for the liberation movements to recruit from the countryside. By 1974 there was about 70.000 soldiers fighting for the Portuguese in Angola. In addition to this there was infighting between the different liberation parties. All of the above factors meant that the liberation struggle had little success up until 1974.

What the uprisings did do was to become a great expense on the Portuguese economy. Between the uprisings in Mozambique, Angola, and Guinea-Bissau there were, in 1974, 250.000 troops fighting for the Portuguese in Africa[clv]. This was a great cost to what was at the time one of the economically poorest nations in Europe. To try and make the colony of Angola more economically self-sufficient a beer industry was encouraged in 1963, which created a thriving economy for the export of alcohol in Angola[clvi]. The colony was also opened up for investments, and at the end of the 1960s American and European companies began great investments in the search and extraction of oil[clvii]. The royalties on oil extracted by Texan oil companies would to a large degree help fund the Portuguese armed presence in Angola. Both South Africa and the United States of America also supplied the Portuguese forces with war materials and arms[clviii]. The MPLA, being Leninist and Marxist oriented, would early on draw assistance from the Soviet Union. In turn the United States of America would support various sides in the long running conflicts in Angola, but initially they supplied weapons to the Portuguese dictatorship[clix].

Even with an influx of money from the oil revenues it was impossible for the Portuguese to hold on to Angola in the long term. The financial and social strain on Portugal to keep up the fighting was too high. In 1970 the Portuguese dictator António Salazar died after having ruled Portugal for 40 years[clx]. Marcello Caetano took power in Portugal 1969, but would never have the solid hold over the country as Salazar did. In August 1973 the Armed Forces Movement (MFA) was founded in Portugal[clxi]. The movement was founded by members of the armed forces in Portugal and they believed that the colonial wars could never be won. They were abhorred by the colonial conflicts and government policies in general. On April 25, 1974, the MFA overthrew the Portuguese government in a coup, and in July that same year they promised independence to the Portuguese colonies of Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau and Angola[clxii]. The liberation struggle had been won by not allowing Portugal to win and through the liberation movements actively protracting the struggle over almost 15 years. In January 1975 MPLA, UNITA, FNLA, and the Portuguese government signed an agreement, the Alvor accords, acknowledging the other parties as legitimate political parties, and pledged to hold elections for a national assembly by October 1975[clxiii]. Portugal would in turn give up power over Angola on the 11 November, 1975.

Angolans who had lived in exile for decades, many part of one of the three liberation movements, returned to Angola and particularly to the capital in Luanda[clxiv]. The plan was for an interim government comprised of UNITA, FNLA, MPLA, and the Portuguese to lead Angola until the elections in October, but by June/July, 1975, old conflicts between the three political parties began to emerge[clxv]. All the three parties mobilised their irregular militias, and fighting ensued in the streets of Luanda. The MPLA had historically the strongest support in the city, and could also call on a large force of militias from the countryside. FNLA and UNITA forces were forced to flee Luanda after some days of fighting. The UNITA forces headed south and FNLA north to the areas which were bastions of their supporters[clxvi]. The MPLA then proclaimed independence of Angola under their leadership alone[clxvii]. With the support of the Democratic Republic of Congo (then Zaire), the FNLA attempted to recapture Luanda in November that same year. Together with about 12.000 Cuban allied soldiers stationed in, Angola earlier that year, the MPLA decisively defeated the FNLA advance[clxviii].

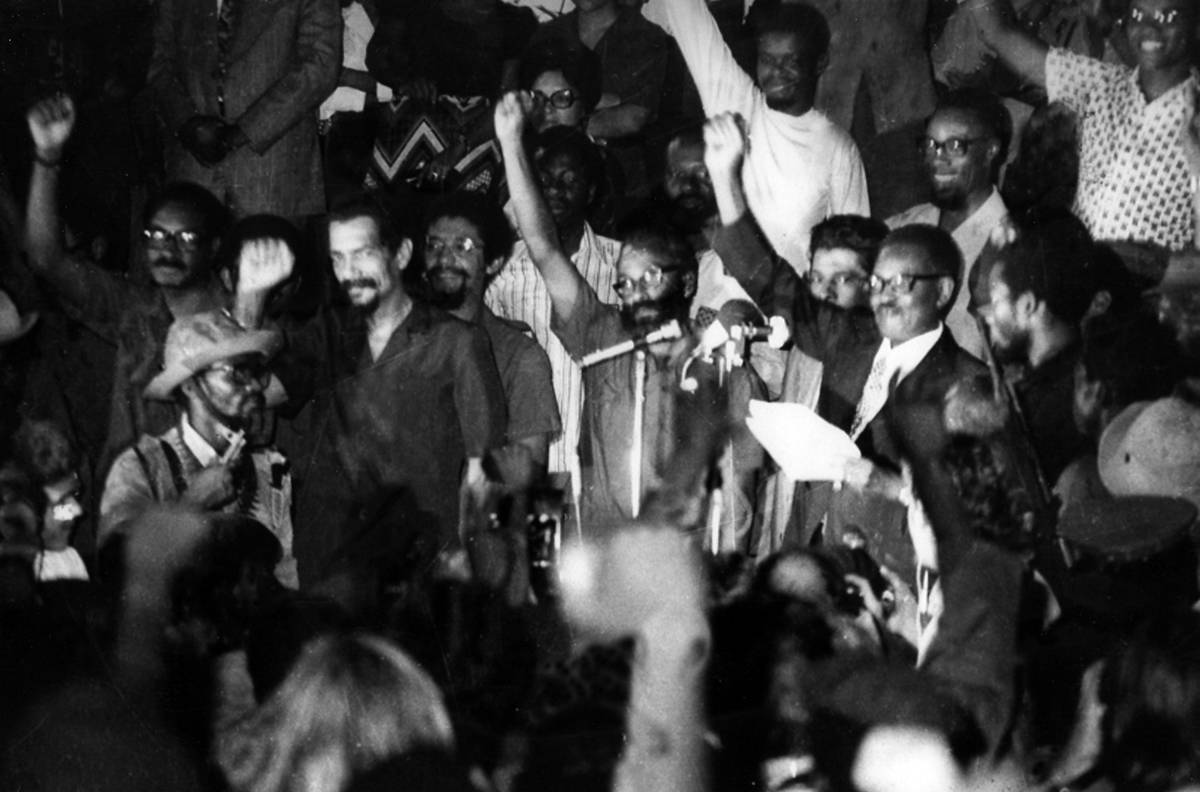

UNITA allied with the apartheid regime in South Africa, which saw the MPLA as a natural ideological enemy, and declared that they would fight the new “colonial oppression” of Cuba and Soviet Union[clxix]. The MPLA advance southwards was halted in September 1975 just as they reached the old kingdoms of Bihé and Huambo which were both UNITA strongholds[clxx]. The MPLA army had managed to stop UNITA and South African forces from advancing further north, but they had not managed to completely defeat them. While the fighting was still going strong in the south and north, the last Portuguese governor left Angola, and on 11 November, 1975, Agostinho Neto proclaimed the establishment of the Peoples Republic of Angola[clxxi]. While the MPLA celebrated independence in Luanda, the FNLA was celebrating in São Salvador (Mbanza Kongo), and UNITA in Huambo[clxxii].

In 1976, after the FNLA was driven out of the country, the MPLA and UNITA had set up distinct areas which they controlled. UNITA ensconced themselves in the southern and eastern highlands, while the MPLA occupied the western and northern parts of the country and in the urban areas as well. This territorialisation would cause people in various areas to strictly identify with one or the other party and help fuel the conflict[clxxiii]. While FNLA was badly beaten UNITA was still standing strong with several international allies (United States of America and South Africa), and the stage was set for a civil war which lasted more than 25 years.

Agostinho Neto declares independence 11 November, 1975. Image source

Agostinho Neto declares independence 11 November, 1975. Image source

The Angolan Civil War

Despite having strong regional and international allies UNITA was not doing well in the beginning of the Angolan Civil War. The United States of America was forced to cut much of their support and make it secretive as their people was not interested in any new foreign adventures after the fiasco of the Vietnam War[clxxiv]. South Africa, the other international UNITA ally, started out with sending a large expeditionary force of about 6.000 soldiers across the border in support of UNITA[clxxv]. The South Africans received massive international condemnation as they were already greatly unpopular because of the apartheid regime, and their intervention was seen as them spreading the apartheid system[clxxvi]. Together with UNITA forces they aided in securing the city of Huambo in the highlands of Angola. This was then set up as UNITA's alternative Angolan capital[clxxvii]. The Soviet Union in turn sent massive aid to MPLA in the tune of $400 million to arm their soldiers[clxxviii].

At the same time the MPLA was trying to set up a post-colonial government and was weakened by the multitude of factions in the party. The power dynamics and segmented hierarchies in colonial Angola had been very complex. MPLA consisted in 1975 of Mestizos (people of mixed backgrounds) and Assimilados (Afrian people which had attained a Portuguese education and habits), white left-wing radicals, urban radicals, the party leadership who had gone into exile, peasants who had been guerrillas in the countryside, or fighters who had held their stance close to the city of Luanda[clxxix]. In addition to the many factions within the MPLA the flight of all of the white public-service personal who had been the core of the governmental bureaucracy created great problems in early days of the new independent government[clxxx]. The Portuguese also left very few functioning institutions (a lot of the newly independent African countries inherited a legal framework, civil service, and an internationally recognised currency) which would be useful to the new political project which the MPLA was engaged in. The factionalism and ideological divisions within the MPLA would exacerbate these issues which in turn made governing the nation even more difficult. UNITA leader Jonas Savimbi used these issues to recruit Angolans to his cause. He also stoked racial tension by accusing the MPLA government of being overly white, and of Luanda being a city of foreigners[clxxxi].

Agostinho Neto meeting with President of Cuba, Fidel Castro. Image source

Agostinho Neto meeting with President of Cuba, Fidel Castro. Image source

For various reasons stated above and because of the continued conflict with UNITA, the MPLA government struggled to live up to the expectations which general people had of an independent Angola. The MPLA's core constituency in Luanda was particularly disappointed with the lack of any radical change[clxxxii]. In May 1977 some of the poor and working-class people were fed up and launched a coup against President Neto's government. The political philosopher and soldier, Nito Alves, was the most prominent leader of the forces behind the coup. Alves was from the area around Luanda and had been one of the seminally independent MPLA commanders who had commanded militia forces in the forests around Luanda[clxxxiii]. His biggest concern with Neto's government was that they had abandoned too much of the Marxist ideology they claimed to support, and that the party was led by elites with no connections to the peasants they represented. Alves created study groups amongst working-class people in Luanda, and one of these study groups inspired a faction of the army led by José Van Dunem to rise up against the government on 27 May, 1977[clxxxiv]. It is disputed amongst historians whether the government or the Nito Alves faction initiated the subsequent violence[clxxxv].

Nito Alves hoped that his popular appeal would inspire to Soviet Union to shift their support to him, but the Russians sat on the fence while the Cubans decisively fought for Agostinho Neto. The rebellion was brutally put down and most of its leadership, including Nito Alves, was executed[clxxxvi]. Thousands of civilians were killed by forces aligned with the ruling regime[clxxxvii]. The attempted coup made the MPLA increasingly authoritative and they now abandoned the egalitarian mass movement model in favour of a more top down dictatorial approach[clxxxviii]. In 1979 Agostinho Neto died of cancer, and he was replaced as president of the country by José Eduardo dos Santos.

In 1978 the Democratic Republic of Congo agreed to stop their support for the FNLA this spelt the final end of the party and its participation in the civil war. The northerners, mostly Bakongo people, who had all fled the country after the uprising in 1961 and the losses in 1975 were now allowed to return home. While the leadership of the FNLA returned to their local towns and villages in obscurity some would return to the political scene over a decade later[clxxxix]. This meant that the north of Angola was relatively at peace, but in the south the war continued against UNITA. With internal rebellions and the burden of governance the MPLA was weakened, and during the late 1970s UNITA, with help of their South African allies, increased their support in the Angolan countryside[cxc]. In 1976 the MPLA had gone out and openly announced their support for the South-West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO) who was fighting the apartheid regime in, what is now called, Namibia. This caused the South African government to increase their support to UNITA. The Soviet Union continued to increase aid to the MPLA, and in the 1980s there was about 50.000 Cuban soldiers in Angola[cxci]. In 1985 the MPLA and their Cuban allies made a major push towards Huambo, but with the help of the South African Defence Force (SADF) UNITA managed to hold on to their capital city. In 1986 in the United States of America the congress lifted the ban on aid to UNITA; this allowed the United States government resume their support.

In 1987 the MPLA forces attempted another attack on Huambo, and again they lost the battle. The South African army decided to pursue the retreating Angolan soldiers all the way to a city called Cuito Cuanavale[cxcii]. The Cubans sent in more soldiers to defend the city, and the battle of Cuito Cuanavale turned into a siege in 1988. Neither side managed to win over the other. The MPLA and the Cuban soldiers were intent on holding the city, but at the same time South Africa refused to give up on UNITA. Eventually both sides claimed that the victory was theirs, partly because of events outside of Angola. By the end of the 1980s the cold war was rapidly coming to an end, and the international backers of the MPLA and UNITA had little interest in continuing the conflict. Both South Africa and Cuba had experienced many causalities, and the Soviet Union was looking towards improving their relationship with the West[cxciii]. On 22 December, 1988, Cuba, South Africa and Angola (MPLA) signed the New York accord. Cuba and South Africa would withdraw support and South-West Africa would become an independent nation under the new name of Namibia[cxciv]. After 1988 the direct engagements and war was now conducted by the two local factions, UNITA and MPLA, alone.

This was a major setback particularly for UNITA as they were dependent on the apartheid regime in South Africa as a neighbour to effectively continue military operations[cxcv]. The other ally of UNITA which helped fuel the Civil War in Angola was the United States of America, especially under the leadership of President Ronald Reagan[cxcvi]. However in March 1990 the Russian and American governments met in Namibia, at the independence ceremony in Windhoek, and agreed to withdraw economic and material support to their respective allies in Angola[cxcvii]. The lack of support from international backers forced the MPLA and UITA leaders to the negotiating tables, and in May 1991 a peace accord was signed in Bicesse, Portugal. The two parties agreed to demobilize their forces and hold national elections for a new government the following year.

Election ballot from the 1992 national elections. Image source

Election ballot from the 1992 national elections. Image source

The peace treaty was widly celebrated by the people of Angola. There was a general sense of optimism that the democratic elections would bring a period of peace and growth[cxcviii]. When the election came on 12 September, 1992, the country was deeply divided in their vote. The urban centers and towns stood firmly behind José Eduardo dos Santos and the MPLA, while the countryside voted for Jonas Savimbi and UNITA[cxcix]. The MPLA won a majority in the new national parliament and also won the presedency. It came as a suprise to Savimbi that the Ovimbundu people, who were supposed to be his support base, had voted against him in the urban areas. The elections had to some degree been a zero sum game, and the loser would be left with no power at all. Savimbi understood that he could only gain power through the barrel of a gun[cc]. On November 1, 1992, war broke out again. This time with increasing intensity and causualties. Most of the disarmament had been a show for international observers, and both sides were prepared for the renewal of the conflict[cci]. UNITA gained the offensive momentum by assulting the MPLA led cities, and by 1994 it is estimated that 60% of the country was controlloed by Savimbi[ccii].

As opposed to the previous Angolan conflicts the cities became a battelground this time in this last phase of the civil war[cciii]. Immediatly after the respumption of the war suspected UNITA members and supporters in the cities were hunted down by MPLA militias, especially in Luanda[cciv]. UNITA on the other hand was attempting to punish the urban centres which had voted against them[ccv]. The countryside was also experiencing brutal violence. UNITA led a brutal campaign against the civilians suspected for being MPLA supporters in the areas they controlled[ccvi]. Landmines had always been in use in the countryside during previous conflicts in Angola, but after 1992 there was an increased use by both sides, and civilians would continue to feel the effects of this for years after the war had ended[ccvii]. Towards the end of the war UNITA, especially, became increasingly brutal against the civilian population and particularly towards refugees trying to escape the war[ccviii].

In 1994 the Lusaka protocol was signed by both sides ensuring a short cease fire, but both sides continued to arm themselves[ccix]. The peace did not last long and in 1998 the two sides were again engaged in open war against each other[ccx]. The MPLA attempted to decisevly crush the UNITA forces, but was unsuccesful, and in 1999 some argue that UNITA even held the military advantage[ccxi]. At the beginning of the new millenium the government forces, fuelled by increased oil revenues, managed to fight back, and by the end of 2001 the had captured one of UNITA’s major bases of operation in the Benguela province[ccxii]. On Februrary 22, 2002, there was a suprising turn of events. Jonas Savimbi had been cornered by government forces near the town of Luena and was killed and secretly buried[ccxiii]. With Savimbi out of the way peace could be a posibility, and representatives from the two parties met to discuss a cease fire. Already in March that year did the MPLA and UNITA agree on a peace treaty so that reconstruction could begin, and in August the UNITA forces were demobilised and integrated into the new Angolan Armed Forces (FAA)[ccxiv]. By the end of the war over 600.000 people wer internally displaced and countless thousands of people had been killed after more than 25 years of war[ccxv].

Abandoned tank from the Angolan Civil War. Image source

Abandoned tank from the Angolan Civil War. Image source

Angola after the Civil War

For 25 years Angola had been devastated by Civil War, and before that it was fighting the brutal oppression by the Portuguese. For centuries the various peoples of Angola had been embroiled in one conflict or another. With the peace agreement in 2002 there was now a space for Angolans to build a nation. UNITA made the transition from a gurriella movement to a legitimate political party immediatly after the end of the Civil War, but there would be six years before the first national elections. Various forms of violence would remain as an effect of the Civil War however. Land mines were still endemic, and political violence surrounding elections would not be uncommon[ccxvi]. In the oil-rich enclave of Cabinda seperatists would continue fighting for independence from Angola[ccxvii]. With the victory over UNITA the MPLA regime was undisputed in its position of power, and it also held a firm hand on the nations oil resources through the oil company Sonangol which the presidency controlled[ccxviii]. The system of power in which the president controlls and dispenses economic resources is called neo-patrimoialism. This system means that the presidency controls the country through giving favours to allies and punishing enemies[ccxix].

The first decade after the Civil War in Angola was one marked by large economic growth, while simultainously being plauged by large scale corruption[ccxx]. There was at this time almost no transparancy in how much Sonagol charged for their oil, or how that revenue was later redistributed. Despite this Angola was by 2004 the fastest growing economy in Africa, and one of the fastest growing in the world[ccxxi]. Much of the growth would come from significant increase in oil revenues and exploration. These years also saw an increasing amount of wealthier Angolans beginning to invest money into the Angolan economy[ccxxii]. The petrolium sector was an unstable industry and the drop in the price of oil in 2015 was a hit to the Angolan economy[ccxxiii]. Despite ups and downs the decades after the Civil War was one of enormous economic growth in Angola. At its height the economy grew by 15,5% of GDP (Gross Domestic Product)[ccxxiv].

A map of the natural resources in Angola. Image source

A map of the natural resources in Angola. Image source

The growth was both a blessing and a curse as Angola’s status upgrade to an emerging economy led to most of the NGO’s (Non-Governmental Organisations) who had run much of the health and education sector withdrew[ccxxv]. Because of the tight control over the economic resources by the political elite affiliated with the MPLA regime the vast growth would not benifit the majority of the Angolan people[ccxxvi]. For example in 2013 Isabel dos Santos, President José Eduardo dos Santos’, daughter was estimated by Forbes Magazine to be the richest woman in Africa, yet the average Angolan person lived on less than $2 a day[ccxxvii]. Urban poverty and lack of proper public health care and education was some of the significant challenges which faced Angola in the decades after the Civil War[ccxxviii].

On September 5, 2008, Angola held its first elections since the elections in 1992, which had disastorous after effects[ccxxix]. The ruling MPLA won an overwhelming victory with 81% of the vote. Second place went to UNITA with 10% of the vote[ccxxx]. This was a drastic change from the elections in 1992 where, while the MPLA won the elections that time as well, UNITA got 34% of the vote and the MPLA got 54%. In 2010 a new Angolan constitution was written which abolished the practice of having direct elections of the president. The person who was head of the wining party in the parliamentary elections would from that point on automatically become president[ccxxxi]. Angola held national elections in 2012 and 2016 and MPLA won both elections and President dos Santos would continue as President. This meant that he had at the time been president in Angola from 1979 to 2016 making him one of the longest reigning heads of state in Africa[ccxxxii].

Endnotes

[i] Iibd. ↵

[ii] Joseph C. Miller. Kings and Kinsmen: Early Mbundu States in Angola, 1976, Oxford: Claredon Press. Page 84. ↵

[iii] David Birmingham, A Short History of Modern Angola, (2015), Hurst & Company: London. Page 41. ↵

[iv] James W. Martin. Historical Dictionary of Angola (Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc: Plymouth, 2011). Page xxxi. ↵

[v] Ibid ↵

[vi] James W. Martin. Historical Dictionary of Angola (Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc: Plymouth, 2011). Page 4. ↵

[vii] Iibd. ↵

[viii] James Denbow. “Congo to Kalahari: Data and Hypotheses about the Political Economy of the Western Stream of the Early Iron Age” in The Journal of African History, Vol. 22, No. 3 (1981).Springer Publishers. Page 141. ↵

[ix] Ibid. ↵

[x] Ibid. Page 143. ↵

[xi] Ibid. ↵

[xii] Ibid. Page 142. ↵

[xiii] James W. Martin. Historical Dictionary of Angola (Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc: Plymouth, 2011). Page 4. ↵

[xiv] James Denbow. “Congo to Kalahari: Data and Hypotheses about the Political Economy of the Western Stream of the Early Iron Age” in The Journal of African History, Vol. 22, No. 3 (1981).Springer Publishers. Page 141. ↵

[xv] Ibid. Page 142. ↵

[xvi] Ibid. Page 141. ↵

[xvii] Ibid. Page 144. ↵

[xviii] James W. Martin. Historical Dictionary of Angola (Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc: Plymouth, 2011). Page 4. ↵

[xix] Joseph C. Miller. Kings and Kinsmen: Early Mbundu States in Angola, 1976, Oxford: Claredon Press. Page 84. ↵

[xx] Ibid. ↵

[xxi] Kamia Victor De Carvalho, Luciano Chianeque and Albertina Delgado. “Inequality in Angola.” In Tearing us Apart: Inequalities in southern Africa, 2011, edited by Herbert Haunch and Deptrose Muchena. Johannesburg: Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa (OSISA). Page 40. ↵

[xxii] Linda Heywood, Contested Power in Angola: 1840s to the Present. 2000, University of Rochester Press: Rochester. Page xv. ↵

[xxiii] Ibid. ↵

[xxiv] Ibid. Page xiv. ↵

[xxv] Thronton, John. 2000. “Mbanza Kongo/Sao Salvador: Kongo's Holy City” in Africa's Urban Past (eds.) David Anderson and Richard Rathbone. Oxford: James Currey Ltd. Page 73. ↵

[xxvi] Thornton, John. 2001. “The Origins and Early History of the Kingdom of Kongo, c. 1350-1550” in The International Journal of African Historical Studies Vol. 34, No. 1 (2001), pp. 89-120. Page 105. ↵

[xxvii] Ibid. ↵

[xxviii] Ibid. Page 106. ↵

[xxix] Gondola, Ch. Didier. 2002. The History of Congo. Greenwood Press, London. Page 28. ↵

[xxx] Gondola, Ch. Didier. 2002. The History of Congo. Greenwood Press, London. Page 30. ↵

[xxxi] Thornton, John. 1984. “The Development of an African Catholic Church in the Kingdom of Kongo, 1491-1750” in The Journal of African History Vol. 25, No. 2 (1984), pp. 147-167. Page 148. ↵

[xxxii] Ibid. Page 149. ↵

[xxxiii] Ibid. ↵

[xxxiv] Ibid. ↵

[xxxv] Heywood, Linda M. 2009. “Slavery and Its Transformation in the Kingdom of Kongo: 1491-1800” in The Journal of African History, Vol. 50, No. 1 (2009), pp. 1-22. Cambridge University Press. Page 2. ↵

[xxxvi] Ibid. Page 4. ↵

[xxxvii] Ibid. ↵

[xxxviii] Ibid. ↵

[xxxix] Ibid. Page 5. ↵

[xl] Ibid. ↵

[xli] Ibid. Page 7. ↵

[xlii] Mariana Candido, An African Slaving Port and the Atlantic World: Benguela and Its Hinterland, (2013), New York: Cambridge University Press. Page 60. ↵

[xliii] Thornton, John. 1977. “Demography and History in the Kingdom of Kongo, 1550-1750” in The Journal of African History Vol. 18, No. 4 (1977), pp. 507-530. Page 519. ↵

[xliv] Heywood, Linda M. 2009. “Slavery and Its Transformation in the Kingdom of Kongo: 1491-1800” in The Journal of African History, Vol. 50, No. 1 (2009), pp. 1-22. Cambridge University Press. Page 8. ↵

[xlv] Ibid. Page 11. ↵

[xlvi] Thornton, John. 1999. Warfare in Atlantic Africa. London: University College of London Press. Page 117. ↵

[xlvii] Ibid. Page 122. ↵

[xlviii] Gondola, Ch. Didier. 2002. The History of Congo. Greenwood Press, London. Page 34. ↵

[xlix] Thornton, John. 1983. The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641-1718. Published by: University of Wisconsin Press. Page 110. ↵

[l] Thornton, John. 1977. “Demography and History in the Kingdom of Kongo, 1550-1750” in The Journal of African History Vol. 18, No. 4 (1977), pp. 507-530. Page 520. ↵

[li] Thornton, John. 1983. The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641-1718. Published by: University of Wisconsin Press. Page 110. ↵

[lii] Heywood, Linda M. 2009. “Slavery and Its Transformation in the Kingdom of Kongo: 1491-1800” in The Journal of African History, Vol. 50, No. 1 (2009), pp. 1-22. Cambridge University Press. Page 22 . ↵

[liii] Thornton, John. 1983. The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641-1718. Published by: University of Wisconsin Press. Page 110. ↵

[liv] Ibid. Page 54. ↵

[lv] Heywood, Linda M. 2009. “Slavery and Its Transformation in the Kingdom of Kongo: 1491-1800” in The Journal of African History, Vol. 50, No. 1 (2009), pp. 1-22. Cambridge University Press. Page 19. ↵

[lvi] Thornton, John. 1983. The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641-1718. Published by: University of Wisconsin Press. Page 115. ↵

[lvii] Thronton, John. 2000. “Mbanza Kongo/Sao Salvador: Kongo's Holy City” in Africa's Urban Past (eds.) David Anderson and Richard Rathbone. Oxford: James Currey Ltd. Page 73. ↵

[lviii] Ibid. ↵

[lix] Ibid. ↵

[lx] Ibid. Page 76. ↵

[lxi] Ibid. ↵

[lxii] Ibid. ↵

[lxiii] Ibid. ↵

[lxiv] Ibid. ↵

[lxv] Ibid. ↵

[lxvi] Ibid. ↵

[lxvii] Ibid. Page 78. ↵

[lxviii] Ibid. ↵

[lxix] Ibid. ↵

[lxx] Ibid. ↵

[lxxi] Ibid. ↵

[lxxii] John Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400-1800, (1998), New York: Cambridge University Press. Page 104. ↵

[lxxiii] James W. Martin. Historical Dictionary of Angola (Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc: Plymouth, 2011). Page xxxi. ↵

[lxxiv] John Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400-1800, (1998), New York: Cambridge University Press. Page 83. ↵

[lxxv] Ibid. Page 109. ↵

[lxxvi] David Birmingham, “The Date and Significance of the Imbangala Invasion of Angola” in The Journal of African History Vol. 6, No. 2 (1965), pp. 143-152. Page 146. ↵

[lxxvii] Ibid. ↵

[lxxviii] Ibid. ↵

[lxxix] David Birmingham, “The Date and Significance of the Imbangala Invasion of Angola” in The Journal of African History Vol. 6, No. 2 (1965), pp. 143-152. Page 146. ↵

[lxxx] John Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400-1800, (1998), New York: Cambridge University Press. Page 109. ↵

[lxxxi] Ibid. ↵

[lxxxii] Linda Heywod and Louis Madureira (translation), “Queen Njinga Mbandi Ana de Sousa of Ndongo/Matamba: African Leadership, Diplomacy, and Ideology, 1620s-1650s” in Afro-Latino Voices: Shorter Edition: Translations of Early Modern Ibero-Atlantic Narratives, Kathryn Joy McKnight, Leo J. Garofalo (eds), (2015), Hackett Publishing Company: Indianapolis. Page 26. ↵

[lxxxiii] Ibid. ↵

[lxxxiv] Ibid. ↵

[lxxxv] Ibid. ↵

[lxxxvi] Ibid. Page 27. ↵

[lxxxvii] Ibid. ↵

[lxxxviii] Ibid. ↵

[lxxxix] Ibid. ↵

[xc] Ibid. ↵

[xci] James W. Martin. Historical Dictionary of Angola (Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc: Plymouth, 2011). Page xxxi. ↵

[xcii] David Birmingham, “The Date and Significance of the Imbangala Invasion of Angola” in The Journal of African History Vol. 6, No. 2 (1965), pp. 143-152. Page 143. ↵

[xciii] Ibid. ↵

[xciv] MacGaffey, Wyatt. 2003. “Crossing the River: Myth and Movement in Central Africa” From International symposium Angola on the Move: Transport Routes, Communication, and History,Berlin, 24-26 September 2003. Page 3. ↵

[xcv] Jan Vasina, “The Foundation of the Kingdom of Kasanje” in The Journal of African History Vol. 4, No. 3 (1963), pp. 355-374. Cambridge University Press. Page 373. ↵

[xcvi] John Thornton, Warfare in Atlantic Africa, 1500-1800, (1999), Millersville University, UCL Press. Page 117. ↵

[xcvii] Ibid. ↵

[xcviii] David Birmingham, “The Date and Significance of the Imbangala Invasion of Angola” in The Journal of African History Vol. 6, No. 2 (1965), pp. 143-152. Page 143. ↵

[xcix] Ibid. Page 144. ↵

[c] Joseph C. Miller, “Kings, Lists, and History in Kasanje” in History in Africa Vol. 6 (1979), pp. 51-96. Cambridge University Press. Page 53. ↵

[ci] Ibid. Page 54. ↵

[cii] John Thornton, Warfare in Atlantic Africa, 1500-1800, (1999), Millersville University, UCL Press. Page 117. ↵

[ciii] Ibid. ↵

[civ] Ibid. Page 120. ↵

[cv] Ibid. Page 117. ↵

[cvi] Giacomo Macola, "Luba-Lunda States" in The Encyclopedia of Empire, 2015, Published by: John Wiley & Sons. Page 3. ↵

[cvii] Ibid. Page 4. ↵

[cviii] Linda Heywood, Contested Power in Angola: 1840s to the Present. 2000, University of Rochester Press: Rochester. Page 1. ↵

[cix] Ibid. ↵

[cx] Ibid. Page 2. ↵

[cxi] Ibid. ↵

[cxii] Ibid. ↵

[cxiii] Ibid. ↵

[cxiv] Ibid. Page 3. ↵

[cxv] David Birmingham, A Short History of Modern Angola, (2015), Hurst & Company: London. Page 41. ↵

[cxvi] Heywood, Linda M. 2009. “Slavery and Its Transformation in the Kingdom of Kongo: 1491-1800” in The Journal of African History, Vol. 50, No. 1 (2009), pp. 1-22. Cambridge University Press. Page 5. ↵

[cxvii] Thornton, John. 1983. The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641-1718. Published by: University of Wisconsin Press. Page 115. ↵

[cxviii] James W. Martin. Historical Dictionary of Angola (Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc: Plymouth, 2011). Page xxxi. ↵

[cxix] David Birmingham, A Short History of Modern Angola, (2015), Hurst & Company: London. Page 55. ↵

[cxx] Ibid. Page 10. ↵

[cxxi] James W. Martin. Historical Dictionary of Angola (Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc: Plymouth, 2011). Page xxxi. ↵

[cxxii] David Birmingham, A Short History of Modern Angola, (2015), Hurst & Company: London. Page 3. ↵

[cxxiii] Ibid. Page 4. ↵

[cxxiv] Ibid. ↵

[cxxv] Ibid. Page 5. ↵

[cxxvi] Ibid. Page 49. ↵

[cxxvii] Ibid. ↵

[cxxviii] Ibid. Page 48. ↵

[cxxix] Ibid. ↵

[cxxx] Robert M. Burroughs, Travel Writing and Atrocities: Eyewitness Accounts of Colonialism in the Congo, Angola, and the Putumayo, (2011), Taylor & Francis: New York. Page 103. ↵

[cxxxi] Ibid. ↵

[cxxxii] David Birmingham, A Short History of Modern Angola, (2015), Hurst & Company: London. Page 60. ↵

[cxxxiii] Ibid. ↵

[cxxxiv] Ibid. Page 61. ↵

[cxxxv] Ibid. Page 62. ↵

[cxxxvi] Ibid. Page 64. ↵

[cxxxvii] Ibid. ↵

[cxxxviii] Ibid. Page 65. ↵

[cxxxix] Ibid. Page 68. ↵

[cxl] Ibid. ↵

[cxli] James W. Martin. Historical Dictionary of Angola (Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc: Plymouth, 2011). Page 8. ↵

[cxlii] David Birmingham, A Short History of Modern Angola, (2015), Hurst & Company: London. Page 68. ↵

[cxliii] Justin Pearce, “Control, politics and identity in the Angolan Civil War” in Afr Aff (Lond) (2012) 111 (444): 442-465, 2012. Page 450. ↵

[cxliv] James W. Martin. Historical Dictionary of Angola (Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc: Plymouth, 2011). Page 8. ↵

[cxlv] Ibid. ↵

[cxlvi] Ibid. ↵

[cxlvii] Ibid. ↵

[cxlviii] Ibid. ↵

[cxlix] Linda M. Heywood, “Angola and the violent years 1975-2008: Civilian casualties” in Portuguese Studies Review, 19(1-2)(2011)311-332. Boston University. Page 316. ↵

[cl] David Birmingham, A Short History of Modern Angola, (2015), Hurst & Company: London. Page 74. ↵

[cli] James W. Martin. Historical Dictionary of Angola (Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc: Plymouth, 2011). Page 9. ↵

[clii] Ibid. ↵

[cliii] Ibid. Page 8. ↵

[cliv] Ibid. Page 9. ↵

[clv] Ibid. ↵

[clvi] David Birmingham, A Short History of Modern Angola, (2015), Hurst & Company: London. Page 73. ↵

[clvii] Iibid. ↵

[clviii] Ibid. Page 74. ↵

[clix] David Birmingham, A Short History of Modern Angola, (2015), Hurst & Company: London. Page 74. ↵

[clx] Ibid. Page 78. ↵

[clxi] James W. Martin. Historical Dictionary of Angola (Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc: Plymouth, 2011). Page 9. ↵

[clxii] Ibid. Page 10. ↵

[clxiii] Ibid. ↵

[clxiv] David Birmingham, A Short History of Modern Angola, (2015), Hurst & Company: London. Page 80. ↵

[clxv] James W. Martin. Historical Dictionary of Angola (Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc: Plymouth, 2011). Page 10. ↵

[clxvi] David Birmingham, A Short History of Modern Angola, (2015), Hurst & Company: London. Page 81. ↵

[clxvii] James W. Martin. Historical Dictionary of Angola (Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc: Plymouth, 2011). Page 10. ↵

[clxviii] Ibid. ↵

[clxix] Ibid. ↵

[clxx] David Birmingham, A Short History of Modern Angola, (2015), Hurst & Company: London. Page 82 ↵

[clxxi] James W. Martin. Historical Dictionary of Angola (Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc: Plymouth, 2011). Page 10. ↵

[clxxii] Linda M. Heywood, “Angola and the violent years 1975-2008: Civilian casualties” in Portuguese Studies Review, 19(1-2)(2011)311-332. Boston University. Page 318. ↵

[clxxiii] Justin Pearce, “Control, politics and identity in the Angolan Civil War” in Afr Aff (Lond) (2012) 111 (444): 442-465, 2012. Page 450. ↵

[clxxiv] James W. Martin. Historical Dictionary of Angola (Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc: Plymouth, 2011). Page 11. ↵

[clxxv] David Birmingham, A Short History of Modern Angola, (2015), Hurst & Company: London. Page 84. ↵

[clxxvi] James W. Martin. Historical Dictionary of Angola (Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc: Plymouth, 2011). Page 10. ↵

[clxxvii] Justin Pearce, “Control, politics and identity in the Angolan Civil War” in Afr Aff (Lond) (2012) 111 (444): 442-465, 2012. Page 450. ↵

[clxxviii] David Birmingham, A Short History of Modern Angola, (2015), Hurst & Company: London. Page 84. ↵

[clxxix] Ibid. Page 85 and 86. ↵

[clxxx] Ibid. Page 86. ↵

[clxxxi] Ibid. Page 87. ↵

[clxxxii] Ibid. Page 88. ↵

[clxxxiii] Ibid. ↵

[clxxxiv] Ibid. Page 89. ↵

[clxxxv] Linda M. Heywood, “Angola and the violent years 1975-2008: Civilian casualties” in Portuguese Studies Review, 19(1-2)(2011)311-332. Boston University. Page 320. ↵

[clxxxvi] David Birmingham, A Short History of Modern Angola, (2015), Hurst & Company: London. Page 89. ↵

[clxxxvii] Linda M. Heywood, “Angola and the violent years 1975-2008: Civilian casualties” in Portuguese Studies Review, 19(1-2)(2011)311-332. Boston University. Page 320. ↵

[clxxxviii] David Birmingham, A Short History of Modern Angola, (2015), Hurst & Company: London. Page 90. ↵

[clxxxix] Ibid. Page 91. ↵

[cxc] James W. Martin. Historical Dictionary of Angola (Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc: Plymouth, 2011). Page 11. ↵

[cxci] Ibid. ↵

[cxcii] Ibid. ↵

[cxciii] Ibid. ↵

[cxciv] Ibid. Page xxxvii ↵

[cxcv] David Birmingham, A Short History of Modern Angola, (2015), Hurst & Company: London. Page 103. ↵

[cxcvi] Ibid. Page 104. ↵

[cxcvii] Ibid. Page 107. ↵

[cxcviii] Ibid. Page 110. ↵

[cxcix] Ibid. ↵

[cc] Ibid. Page 111. ↵

[cci] Ibid. Page 110. ↵