Newspapers or publications by African people played a critical role in giving them an alternative space to articulate their views. The emergence of a number of publications in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century spearheaded by the emerging African elite was incorporated into the struggle for increased political rights. Newspapers such as Imvo Zabantsundu, (Native Opinion) founded in 1884 by John Tengo Jabavu, Izwi Labantu (Voice of the People) established in 1897 by Allan Kirkland Soga, Koranta ea Becoana (Bechuana Gazette) set up in 1901 and Tsala ea Batho which began in 1910 and were both established by Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje, are evidence of increased recognition of the power of the pen by the African intelligentsia.

As the use of the newspaper as a medium of communicating African ideas, views and demands flourished, the Abantu-Batho emerged. The newspaper was established in October 1912 and launched in Johannesburg. Historian Les Switzer notes that the newspaper was primarily formed through the efforts of Pixley ka Isaka Seme. It received impetus when Motsoalle (Friend), a newspaper established by Daniel Simon Letanka, merged with Abantu-Batho in 1912 at the request of Pixley Seme. Letanka went on to become one of the directors of the company that published the newspaper. Labotsibeni, the Swazi Queen Regent provided financial assistance which was key in the founding and sustaining the paper. Abantu Batho newspaper was established chiefly as an official mouthpiece of the newly established South African Native National Congress (SANNC), later renamed as the African National Congress (ANC).

The newspaper was published in English, SeSotho, Zulu, Xhosa and SeTswana in order to attract wide readership and honour the SANNC’s goal of being a national organization. Four editors were appointed to oversee the publication of content while Seme supervised the project as the first managing editor. For instance, Cleopas Kunene was the editor responsible for the Zulu and Xhosa sections, while Letanka was the editor overseeing the SeSotho and SeTswana sections. Notably, all five of these individuals were also directors of the company that published the newspaper. Other editors from the papers lifetime included Saul Msane, Richard Victor Selope Thema, Jeremiah W Dunjwa and TD Mweli Skota.

The paper’s popularity increased to such an extent that according to historian Andre Odendaal, “Abantu-Batho became the most widely read newspaper amongst Africans in South Africa.” It was published irregularly for over two decades sometimes weekly, monthly or bimonthly depending on the finances. Contributors to the paper included Davidson Don Tengo Jabavu, Samuel Makaba Masabalala, Samuel Edward Krune MqhayiSamuel M Bennet Ncwana and Zaccheus Richard Mahabane.

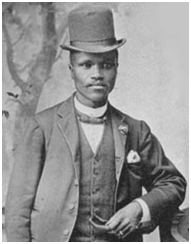

Prominent Xhosa poet Samuel Edward Krune Mqhayi was one of the contributors to Abantu-Batho

Prominent Xhosa poet Samuel Edward Krune Mqhayi was one of the contributors to Abantu-Batho

The content of the paper addressed a variety of issues affecting Africa people. For instance, after the passing of the Natives Land Act in 1913, the newspaper condemned the Act arguing that it had reduced Africans to “penury and want.” The paper challenged the horrendous conditions of workers, too. It complained that despite the essential role played by the workers in the economy, they were not adequately paid. It also took an interest in female workers and rights. For instance, between 1917 and 1918 the paper published detailed reports of women to organize themselves and gave coverage to Charlotte Maxeke, a women's organiser, who urged women “to get themselves ready for the struggle.” Furthermore, the paper reported the bucket strike of July 1918 by municipal workers, the anti-pass protests in 1919 and the 1920 African Miners Strike. Workers were praised for their defiance and encouraged to read the paper to remain informed.

The newspaper was not without its critics from rival publications also competing for the same readers. A publication by the International Socialist League (ISL), the International, accused Abantu-Batho of being edited under the supervision of the Native Affairs Department and being an agent of the capitalist press. However, this was not supported by content of the newspaper as it focused on criticizing the exploitation of African labour, the imposition of pass laws on women and work contracts imposed on domestic workers.

The increasingly radical views of Abantu-Batho unsettled mine owners particularly after the 1920 African mine workers strike. As a result the Chamber of Mines established its own weekly newspaper Umteteli waBantu (Mouthpiece of the People) which was edited by Africans and competed for the same readership as Abantu-Batho. The first editor was Reverend Marshall Maxeke, who was succeeded by A.R. Mapanya in 1922. Its aim was to dispel “certain erroneous ideas cherished by many natives and sedulously fostered by European and Native agitators and by certain Native newspapers.” (Brian Willan, Sol Plaatje A Biography, 1984, p. 251).

It is worth noting that the idea of establishing an alternative newspaper to Abantu-Batho came from the conservative elements of the SANNC who resented the influence of the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) in the SANNC. Saul Msane and Isaiah Bud M’belle, political leaders in the Transvaal, approached the Chamber of Mines in 1919 with the request for support to establish an alternative paper to Abantu-Batho but it was turned down. After the strike of 1920, the idea was resurrected by the Chamber of Mines and Umteteli waBantu was established. Africans, particularly members of the CPSA, criticised the paper calling it a tool of the mining industry. This was perhaps driven by the paper’s refusal to support protests by African workers and its stern criticism of communism.

The newspaper went through a difficult period in the 1920s when it was crippled by financial constraints. As an attempt to save the paper, Josiah Tshangana Gumede bought the majority of shares in the company in 1929 giving him a controlling stake. In April 1930, Gumede lost presidency of the ANC to Pixley Seme. The following year in July 1931 Abantu-Batho ceased publication. Seme, the paper’s founding member, attempted to promote Ikwezi le Africa (the Morningstar of Africa), another newspaper that he started in 1928 as the official organ of the ANC. His attempt failed and Ikwezi le Africa was incorporated into the African Leader, a newly established official mouthpiece of the organization.