This article was written by Bennett Gwynn and forms part of the SAHO and Southern Methodist University partnership project

Overcoming Adversity from All Angles: The Struggle of the Domestic Worker during Apartheid

Nobengazi Mary Kota is a South African domestic worker for a wealthy family in Cape Town; when asked in 2004 about the world that the domestic workers lived in during apartheid she said: ‘A look at gender, domesticity, mobility and citizenship in [South Africa] indicates that the world of domestic workers is one of uncertainties, insecurities, and dehumanisation, even in the midst of abundance and rhetoric of rights and entitlements’ (Cock 181). Domestic workers in South Africa during apartheid lived oppressed and difficult lives. They had to endure extreme racial prejudice and demeaning social norms that degraded their existence as people. The workers and their employers had a parasitic relationship; the employers underpaid and undervalued the servants due to their race and position in society. The workers had an incredibly difficult time changing their relations with employers for a multitude of reasons. The intense racial tensions during apartheid paired with the struggles of organising a spread out and disorganised work force were two big problems the domestic workers had to solve in order to improve their lives. Those two problems caused the domestic workers great pain and suffering in their journey for a better life, but their perseverance eventually paid off and they achieved their goal of unionising. The domestic workers in South Africa at first struggled to unionise, but once they did, they were able to influence legislation and gain benefits that helped them better their lives, but domestic workers still experience difficulties in the modern day due to racial relations and tensions between employers and employees.

The relationships between the domestic servants and their employers symbolised racial relations between Black and White South Africans during this time period. Domestic workers in South Africa were Black women forced into working for whites due to apartheid’s brutal restrictions on jobs they could perform. Black people during apartheid by law could not perform any skilled labor (The Labour Department of South Africa). Sue Gordon, a history professor at the University of Illinois, claims that Black South African women ‘had no other hope or prospects for decent jobs or accommodation incentives except to work as domestic workers, for the house-holders and perform undesirable dirty jobs’ (Gordon 15). The domestic workers were given incredibly low salaries and lived in ‘servants quarters’, which for some were shoddy at best (Gordon 27). There was no minimum wage provided to the workers, thus they were subject to the wages given by their employer. The workers were looked down upon and treated more like slaves than servants. Jacklyn Cock, a professor at the University of Witwatersrand, describes their helpless situation: ‘The maids in South Africa are indeed as a rule powerless and extremely vulnerable to manipulation and abuse’ (Cock 182). The domestic workers were forced to accept their role as inferior to their employers and had to put on masks to hide their frustrations and outrage, for they were worried about their employment being terminated. Rebecca Ginsburg, a South African historian, describes the general attitude amongst the workers in her book At Home with Apartheid: ‘Maids seldom displayed overt signs of dissatisfaction, their voices of complaint were rarely heard’ (Ginsburg 184). The workers countered these horrible injustices in different ways.

One way for the domestic workers to counter their dreadful treatment by their employers was to feign ignorance and put on a ‘mask of deference’ (Gordon 182). This was an effective strategy for them to adopt because if their employers saw any personal expression or abnormal behavior they would terminate their employment. For example, if a worker was to show up to work not in their uniform, which for most workers was an apron and headscarf, they could be fired that very day (Cock 38). Some domestic workers sought refuge from these atrocious working conditions by reminding themselves that they were still getting paid and supporting their families. Ankia, a domestic worker for a family in Johannesburg, explained her reasoning for why she endured the hardships in the home: ‘Our place is very poor”¦that is why we come to Johannesburg to work here”¦ because our place is very very poor’ (Ginsburg 31). Another worker, Boudine, explains that domestic work was so common in her community that it would be almost abnormal to be a woman and not work in a home ‘when you see all your friends your age going to town you say, “I can’t stay here by myself. All my friends are going to work”, I must also go to work’ (Ginsburg 34). However, not all South African domestic workers were willing to work without any form of protest or complaint.

Some domestic workers would frequently gossip about their employers to the other domestic workers as a coping mechanism, ‘The maids’ silence and mockery of employers could be viewed as muted rituals of rebellion and as a crucial mode of adaptation, a line of resistance that enabled them to maintain their integrity’ (Cock 184). The domestic workers knew their employers’ daily schedules and would orient their ‘free time’ around the times when their employer was absent. Ginsburg writes that: ‘they used their employers’ comfortable beds to rest their tired bodies, washed their own clothes in their washing machines, and bathed in their tubs’ (Ginsburg 150). Cock claims that the workers were cognizant of their exploitation. She writes, ‘they did not accept the legitimacy of their own subordination in the social order, they were highly conscious of being exploited and quite aware of the structures that made this possible’ (Cock 185). There was a community of domestic workers that took solace in discussing their atrocious living conditions and working environments with their fellow partners in trade. This sense of community assisted in starting a push for unionisation and organisation, but these goals were hard to achieve for a multitude of reasons.

Saying it was difficult for the domestic workers in South Africa to unionise would be an understatement at best. An important limiting factor in their attempts to unionise was that some domestic workers’ permanent residences were often on the property of their employer, making it very difficult for them to attend any meetings without arousing any suspicion (Gordon 45). The employers were prone to terminate their domestic workers immediately, at any sign of submissiveness or disobedience. Simply put, the employers of the domestic workers did not want to pay more than the low wages they were providing (Ginsburg 45). Another issue the domestic workers faced in their battle to unionise was that the workers were not all in similar locations, like the miners were, thus it was difficult for them to converge and discuss forming a union and fighting for their worker’s rights.

One of the main combatants of the domestic workers efforts were the laws that governed the country. Apartheid legislation played a big role in hindering the workers efforts of unionisation. The domestic workers in South Africa either lived on the property of their employer or in the government sanctioned townships created by the group areas act of 1950 (Group Areas Act (South Africa [1950]). This act deterred the domestic workers unionisation because they had no main area to convene and discuss their goals as a workforce. Another important piece of apartheid legislation was the Native Labour Regulation Act of 1911 (Native Labour Regulation Act), which prevented any Black African from going on strike or attempting to unionise. The act was crippling to the Black South African work force because any attempt to improve their conditions, whether it be through unionisation or going on strike, could be legally reprimanded by the brutal South African police force (Ginsburg 68).

Another deterrent of their unionisation effort came from men. Domestic workers in South Africa were not the only people hoping to obtain their individual rights and freedoms. Multiple work forces, from the miners to the other male workers who commuted to the city, were all fighting to combat the labor laws that affected their lives so much (Cock 76). Domestic workers struggles were not fully understood by the rest of their community because of two main reasons. The first reason was that the vast majority of all domestic workers at the time were women and most men at the time believed that work that women did was not nearly as demanding or challenging as a man’s because men believed that women were inferior (Cock 68). The second reason ties into the first. In the 1960s, when domestic workers first began to migrate to the big cities in order to work, the men believed that the women’s jobs were not difficult at all. They could not understand how working in a house was so demanding and brutal. The men understood the racial neglect and verbal abuse because they experienced the same thing every day because of the colour of their skin, but they considered domestic work to be inferior to any form of male labor because they could not understand the psychological aspect of the women’s jobs. Men equated job difficulty solely upon how physically rigorous the job was and had no consideration of any other factors that would make a job difficult (Cock 72). These three main facts of life during the apartheid era provided great resistance in the efforts of the domestic workers to unionise. However, they never stopped trying to obtain their goal of wage legislation and better working relationships.

The domestic workers’ efforts to unionise were slow and methodical. They knew that they would have to be careful and cautious about how they went about achieving their goal. They were incredibly hesitant to do anything that might arouse suspicion from their employers and some did not even want to try and risk it at all (Cock 45). Domestic workers began their protest in 1957 when they began protesting the pass laws. These protests led to the eventual crackdown legislation of the apartheid government. In 1960 the South African government passed legislation that made it illegal to be involved in any political organisations. Then later, in 1964, the South African government passed a law requiring all black women to carry passes, which ignited protest from women because of the inconvenience of having to carry their passes with them at all times (Macmillan 123). The employers would often ask their domestic workers if they had their passes on them because they wanted to make sure they were ‘trustworthy’ and were not going to rebel against their rules (Ginsburg 56). After the government initiated these pass laws the domestic workers thought that they had no chance of ever unionising or getting wage legislation because of how restrictive and difficult the government was being towards domestic workers (Ginsburg 64). However, with the rise of outrage over apartheid from the Black South Africans in this time period, the domestic workers would make major progress in the next decade.

In 1973 trade unions began striking heavily, which created a climate of uprising and rebellion in South Africa. A key piece of legislation was passed in 1973, the Bantu Labour Relations Amendment Act, which permitted Black workers the legal right to strike (South African Department of Labour). In 1974, more progress for unionisation was made when the Trade Union Council of South Africa permitted black members, disbanding the Native Labour Regulation Act (Gaitskill 150). The unrest over apartheid was ubiquitous in the Black South African community and conflict was inevitable. Student protests helped fuel the fire of anti-apartheid fervor, specifically the Soweto student uprising in 1976. The Soweto incident directly affected the domestic workers because they were heavily invested in their children’s education. They wanted their children to have the best education possible, so when the government declared Afrikaans the official medium of instruction in Black South African schools, the students and their parents were outraged (Cock 45). In 1980 the domestic workers began organising their efforts to protest for the educational rights of their children. From this time on, the domestic workers made great gains in their fight for labor rights and unionisation.

In 1983 the United Democratic Front was created in order to oppose state practices of separate government. The 1980s in South Africa were incredibly violent and riddled with protests and resentment about the government. The domestic workers’ efforts towards unionisation and rights were growing considerably and their employers were taking notice. Some workers were fired. Some employers began treating the workers worse and were starting to force them to stay and work in the homes permanently to make sure they were uninvolved in the protests (Gordon 134). Domestic workers began to hold meetings and built a network of people within their communities. They would lie to their employers and meet in specific stores in South Africa and discuss unionisation strategies and meeting times (Gordon 155). Their efforts finally paid off.

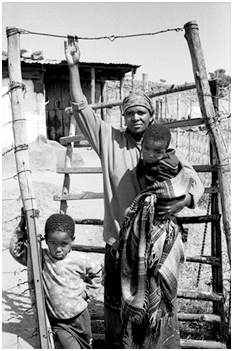

The Pheko Family, Entrag Farm, Heidelberg. 2005. Photograph by JÁ¼rgen Schadeberg. Permission: Schadeberg. Photograph showcases the contemporary living conditions of Black South African families. Image source

The Pheko Family, Entrag Farm, Heidelberg. 2005. Photograph by JÁ¼rgen Schadeberg. Permission: Schadeberg. Photograph showcases the contemporary living conditions of Black South African families. Image source

In 1986, the domestic workers finally formed their union. The South African Domestic Workers Union, or SADWU was comprised mostly of women who worked in the homes of white people who lived in Cape Town. The union was established in order to gain credibility amongst the South African people and raise awareness for their rights as workers. After the union was created, it was much easier for the workers to organise and plan protests and make their voice heard (Ginsburg 145). The domestic workers also fought for gender rights in South Africa and were a driving force in the first conference for gender and women in 1990, which established the Women’s National Coalition (Cock 112). The WNC was a group dedicated to equal gender rights for women. The coalition assisted in the passing of the Basic Conditions of Employment act, which protected Domestic workers from wrongful termination and gave them legal rights in court (South African Department of Labour). After the election of Nelson Mandela in 1994, more legislation was passed in favor of domestic workers. The Labour Relations Act of 1996 and the Basic Conditions of Employment Act of 1997 established a minimum wage for domestic workers and created laws that helped regulate their work hours and living conditions. These acts made it illegal to house the domestic workers in spaces that were inhospitable and unlivable (South African Department of Labour). The domestic workers fought hard for their goal of unionsation and the improvement of working conditions and achieved them, but their lives certainly are not easy in the modern day.

Contemporary gender and race relations in South Africa are still very tense and the domestic workers in South Africa experience the consequences of these relations every day. The unionisation of the workers and the legislation passed in favor of them helped the workers’ lives, but the workers are still vulnerable to being taken advantage of. Most domestic workers are very uneducated and are the daughters of domestic workers. Thus, most domestic workers are bound by their genes to work for families their whole lives (Cock 68). Another important factor in their lives is their salaries. While a minimum wage was established, this did not help the workers out financially as much as they originally anticipated. More than half of the domestic workers’ salary is the minimum wage (Dinkleman 78). This causes the workers to live in poverty and only makes their lives more difficult. A main problem for domestic workers lies in the nature of their job. Taryn Dinkleman, an economics professor at Dartmouth, explains the workers economic conundrum. ‘It reflects class differentiation and prices one job as valuable over and above others”¦they do not have any say in the employment relationship’ (Dinkleman 89). The employers of the domestic workers still see their domestic workers as inferior to them, because they have a lot of control over their daily operations. Dinlkeman explains, ‘it is a form of servitude within South Africa’s modernising racial capitalism”¦it reproduced the racialised logics of apartheid that construed blacks as a servant class’ (Dinkleman 104). The International Labour Organisation’s stated position on the domestic worker in South Africa is that they are ‘on the supply side of rural poverty, gender discrimination in the labour market as well as limited employment opportunities in general’ (Dinkleman 130). The lives of the South African domestic workers are still difficult to this day.

In conclusion, the South African domestic workers were incredibly oppressed during apartheid and have improved their lives since its abolition, but they still encounter many difficulties on a daily basis. Their creation of SADWU and legislation like the Basic Conditions of Employment act brought them credibility and organisation as a work force, but their employment is still beset with feelings of inferiority and racial prejudice. The domestic workers of South Africa are still living in a racially tense climate and experience the effects of apartheid on a daily basis.