Rwanda is a land-locked Country located in the Eastern part of Africa. People began settling in the area as early as 10.000BCE[i]. After several successive waves of migrations Rwanda saw the formation of several smaller Kingdoms in the 1100s; and by the 1500s a larger and more centralised kingdom known as the Kingdom of Rwanda emerged[ii]. The Kingdom of Rwanda was ruled by the Mwami (King), and the kingdom reached the height of its territorial expansion in the late 1800s[iii].

In 1899 Rwanda was colonised by the German Empire as it was officially incorporated into German East Africa and ruled indirectly through King Musinga's puppet government[iv]. Rwanda was only a German colony for a short period of time, however. With the German empire's defeat in World War I Rwanda became absorbed into the Belgian colonial empire as part of a mandate from the League of Nations (later United Nations). The Belgian colonial occupation had a much more lasting effect in Rwanda[v]. The most lasting effect was how the colonial authorities racialised the differences between Hutu, Twa and Tutsi[vi].

Rwanda gained independence from Belgium in 1962, but the post-colonial period was marred by ethnically motivated violence. This violence culminated into the 1994 Rwandan genocide in which more than 800.000 Tutsi people were killed, including thousands of Hutu people who were either part of the opposition or who had refused to take part in the killings[vii]. The period after the civil war was one of impressive Growth Domestic Product (GDP) growth, which reached 8% in 2005[viii].

Rwanda has a long and contested history. A post-colonial history marked by internal conflict and ethnic genocide has impacted how people see the role of various ethnic groups in pre-colonial Rwanda as well[ix]. The early history of Rwanda, and especially the role and nature of the country's three dominant ethnic groups namely the Twa, Hutu and Tutsi, is highly debated amongst academics, politicians and people in general[x]. What is important to remember is that cultural and ethnic belonging is always fluid and changing, and in as much as this is a product of contemporary politics, this is historically determined. Some argue that historians were complicit in fuelling the post-colonial violence and genocide in Rwanda by accepting and reproducing the colonialist notion that Hutu, Twa and Tutsi people where distinct “races”[xi].

Early history of Rwanda

The first inhabitants of the area that is now Rwanda settled there at least 10 000 years ago, during the Neolithic period[xii][xiii]. They were hunter-gatherers and lived in the forests, being later identified as the Twa people[xiv]. They were engaged in hunting and gathering of food and the crafting of pottery[xv]. By 600CE the people living in the area knew how to work iron, had a small amount of cattle and planted small amounts of sorghum and finger millet[xvi].

Between 400 – 1000 CE[xvii] migrants from central Africa brought with them more extensive knowledge of agriculture and farming[xviii]. They engaged in agriculture, had small herds of livestock and were later identified as Hutu people[xix]. The last wave of migrants were cattle herding pastoralists who were fleeing famine and drought (either from central or east Africa) and settled in Rwanda between 1400 and 1500CE[xx]. The last group were identified as the Tutsi people after the 1600s[xxi]. These migrations arose in slow and steady waves and did not occur thrugh invasions and conquest. There was also a great deal of cohabitation and intermarriage[xxii][xxiii]. To this end there was a large degree of integration, acceptance and interaction between the different groups who arrived at different times[xxiv].

Farmlands in the Rwandan countryside. Image source

Farmlands in the Rwandan countryside. Image source

Some historians even argue that there was almost a seamless stream of population movement and not any trace of large grouped migrations with distinct modes of production[xxv]. In this perspective the pastoralist class emerged because of an increase in the cattle population through cattle raids[xxvi]. Following this line of reasoning there would be no pre-colonial historical grounds for the ethnic groups which have dominated contemporary Rwandan history.

In any event, by the 1900s the three dominant ethnic groups were deeply integrated to the point where it would have been difficult to tell them apart. The groups had a shared language, many of the same cultural practices and believed in the same religion[xxvii]. It was mostly through their means of production, cattle herding (Tutsi), farming (Hutu) and hunter/gathering (Twa) that distinctions were made[xxviii]. Furthermoe, because they utilised different modes of production there were issues of difference between the Twa and the rest of the Rwandan peoples. The forest dwelling Twa were engaged in hunting and gathering and they were naturally opposed to a pastoral/agricultural economy, as this required the clearing of forests to open up land[xxix]. This had the effect that there was less intermarriage and co-operation between the forest dwelling people and the other two groups, than there was between people who farmed or owned cattle.

During the early period clans, or ubwoko[xxx], were the dominant broader social organising principle rather than ethnicity (which would only really be an important signifier of social relationships in the colonial period)[xxxi]. Each clan had a patriarchal figure, known as “father of the clans” who would coordinate clan based activities[xxxii]. The clans were constituted through a mythology of a shared patrilineal descent, where people traced their origins through the male lines of their families[xxxiii]. In reality this was more like a system of alliances between smaller family units, called inzu[xxxiv].

The clans would remain important signifiers of belonging throughout Rwanda's history and would often constitute people from all of the three ethnic groups of Hutu, Tutsi and Twa[xxxv]. In the 1300’s and 1400s the clans began to form more rigid structures around clan leaders, turning the “father of the clans” into hereditary kingships[xxxvi]. As an increasing amount of power and wealth was accumulated by a single person at the head of a clan Rwanda saw the emergence of a variety of small hereditary kingdoms[xxxvii]. These Kingdoms were ruled by an aristocracy of powerful cattle herders, with a King as the symbol of sovereignty. By the 1500s Rwanda was made up of a myriad of smaller kingdoms.

The Kingdom of Rwanda

Some academics believe that a shortage of land created increased conflict over cattle to be used as lobola, and that this created a class of warriors amongst the mainly Tutsi people who practised pastoralism[xxxiii]. The degree of how expansive the influence of the Kingdom of Rwanda was is debated however[xxxix], but what is clear is that in the 1400s, through conquest of several smaller chiefdoms, a state was formed around the Mwami (or king) of Rwanda[xl].

Reconstruction of the Palace of the Mwami of Rwanda. Image source

Reconstruction of the Palace of the Mwami of Rwanda. Image source

In the 1600s the Mwami established a hierarchical system called ubuhake where people who farmed (Hutu) would give their service and crops to the pastoralists (Tutsi), in exchange for use of land and cattle[xli]. Through the ubuhake system a Hutu farmer could acquire cattle and, with a large enough herd, become a Tutsi pastoralist[xlii]. Usually the system was based on a client giving services to a wealthy patron in exchange for cattle and land[xliii]. So the ubuhake system had a certain kind of social mobility that was more founded on clan affiliation than ethnic division. However, some historians argue that there was less fluidity between these social classes in the Kingdom of Rwanda than in the Kingdom of Burundi[xliv].

Through critical engagement with the ibiteekerezo (a special form of Rwandese storytelling or royal poetry) we know much about the Kingdom of Rwanda, and the royal dynasty of Nyiginya (who ruled the Kingdom)[xlv]. Because these stories are sometimes contradictory and shrouded in mythology, there is much about the early history of the Rwandan Kings that we cannot say for certain[xlvi]. Some of the Kings are known and much spoken about, but a comprehensive and historically conclusive list of Kings and the exact periods they ruled would be difficult to compile with accuracy[xlvii].

What we know about the kingdom is that it was around the Nyiginya dynasty that the Kingdom of Rwanda was first constituted into a nuclear state[xlviii]. The mythical founding father of the Kingdom of Rwanda was Gihanga, but it is debated whether he was a real historical figure or not[xlix]. With some historical accuracy we know that Mwami Ruganzu I Bwimba was the king which began the process of expansion which would firmly establish the nucleus of the Kingdom of Rwanda[l].

In the 1600s Mwami Ruganzu II Ndori oversaw a second period of expansion and conquered several smaller kingdoms in and around the central parts of Rwanda[li]. Up until this point most of central Rwanda had been constituted by a series of smaller kingdoms, which were associations of chiefs centered around a king[[lii]. Umwami Ruganzu II Ndori's conquests, and his efforts to centralise power into his family, was the true beginning of Rwanda as a hereditary monarchy,[liii] especially as he was instrumental in establishing the ubuhake system of patronage[liv].

The actual extent of the influence and power that the Kingdom wielded is debated[lv]. What is clear is that the 1400s to the early 1900CE was a period when the Kings and nobility of Rwanda expanded their control of the periphery until the Kingdom was about the size of the contemporary nation-state of Rwanda. It is estimated that in 1700 the Kingdom of Rwanda only made up about 14% of contemporary Rwanda, and that the following 150 years was a period of great expansion of its borders[lvi]. Mwami Kigeri IV Rwabugiri who ruled from 1860 – 1895 was the final architect of Rwandan unification and expanded the Kingdom beyond its current borders (including some areas of present day Uganda)[lvii].

The Mwami ruled with the help of an array of chiefs and advisers. The military chief was in charge of army and land distribution after conquest. The cattle chief regulated disputes over cattle and the land chief was in charge of land and agriculture[lviii]. In the palace the Mwami took advice from the Queen mother and an advisory council known as the Abiru[lix]. Some historians claim that this system of chiefs and advisor’s guarded the common people from abuses of power by the kings and the nobility[lx]. The King would have a personal guard of young professional warriors from his kin group to protect him and help him enforce his rule[lxi].

In 1884 events in Europe would profoundly change the historical trajectory for the Kingdom of Rwanda. During the Berlin conference, without any consultation with the Rwandan people, it was decided that Rwanda would be part of the German Empire[lxii]. In 1890, despite no European ever having even visited the country, the Kingdom was incorporated into a German East Africa protectorate[lxiii]. Two years later, in 1892, the first European, a German named Oscar Bauman, entered the Kingdom of Rwanda[lxiv].

Colonial occupation of Rwanda

In 1894 Mwami Kigeri IV Rwabugiri met with the German Captain von Götzen[lxv]. A year later the King of Rwanda died and was succeeded by his young son Mibambwe IV Rutarindwa[lxvi]. His rule would be short as that same year he was deposed in a bloody coup, by Yuhi V Musinga, which saw much of the old King's immediate family killed[lxvii]. The German army then helped the new King pacify the any opposition in the country, especially this suppression target an uprising of farmers in the northern part of Rwanda[lxviii]. With the quelling of Rwandan resistance (although rebellions would continue until at least 1920) in 1899 Rwanda was officially incorporated into German East Africa, and ruled through King Musinga's puppet government[lxx].

In the beginning of colonial rule there were some large scale uprisings. In 1907 one of the wives of the late Mwami Rwabugiri, named Muhumusa, rose up against the German authorities[lxxi]. She crowned herself Queen of Ndorwa and proclaimed that she would cast out the foreign invaders[lxxii]. Muhumsa later fled to Uganda and was captured by British forces there in 1911. Her son, Ndungutse, continued the rebellion and received widespread support in the northern part of Rwanda. Ndungutse was killed by German forces a year later in 1912, but the north continued to resist the colonial authorities[lxxiii].

Besides putting down the uprising in the north, and consolidating the borders of Rwanda at its contemporary size, the German colonial authorities did not change much of Rwandan society[lxxiv]. The colonialists ruled through a system known as indirect rule, where local authorities would rule on behalf of the colonial power[lxxv]. This meant that all the institutions of the King and aristocracy remained intact, but they were at the mercy of their colonial overseers. The local authorities would then coerce forced labour through the same client-patron that existed before colonial conquest, but the labour would be used to build infrastructure and extract resources to benefit the German empire rather than the local elite[lxxvi]. The effect of indirect rule was the division of the Rwandan population in a manner that deflected anti-colonial sentiment and popular anger away from the colonial occupiers and towards the local elite[lxxvii]. This had a profound effect on post-colonial Rwanda as it would be a constant source of internal conflict and genocidal violence.

Rwanda was only a German colony for a short period of time, however. With the German empire's loss in World War I Rwanda was transferred to become part of the Belgian colonial empire as part of mandate from the League of Nations (later United Nations). The Belgian colonial occupation had a much more lasting effect in Rwanda[lxxviii]. They added more aspects of direct rule, taking a greater part in the everyday administration of the colony, making Rwanda a unique mix of indirect and direct rule[lxxix]. As part of their efforts to control the Rwandan people they enlisted the Catholic church and the missionaries to indoctrinate people, especially the aristocracy, towards a European disposition[lxxx]. In 1930 the Catholic missionaries also took over all primary schooling in the country, and Tutsi children were told that they were better than Hutu, and the education for Hutu children was only meant to prepare them for manual labour[lxxxi].

The Belgian colonial authorities would continue the German policy of cementing Hutu and Tutsi identities into permanent and biologically determined racial categories[lxxxii]. Previously these were fluid identities which people moved in and out off depending on the work they did and their status in society. The colonial government made them permanent markers, people were either Hutu or Tutsi and you were born into one or the other.

Contemporary academics and colonial officials could not believe the advanced nature of Rwanda's central government. To explain it they constructed a narrative of Tutsi people as a “Hamitic” people who immigrated to Rwanda from Ethiopia[lxxxiii]. The people categorised as Tutsi were then favoured for the most prestigious work and with a greater amount of power and decision making through the aristocracy and the King. This was cemented with the colonial reform between 1926 and 1936, which made it so that all Hutu people would be ruled by Tutsi leaders[lxxxiv]. Through changes in the legal system and mandatory identity cards to specify whether people were Hutu or Tutsi the Belgians had constructed the Hutu and Tutsi as two distinct races. The Hutu was the indigenous “Bantu” people, and the Tutsi was the “Hamitic” invaders[lxxxv]. This division was a catalyst for violence in post-colonial Rwanda.

The 1920s was a period of taking power from the Mwami and giving it to smaller chiefs. After 1922 the Mwami had to consult with the colonial authorities before he could make legal decisions. The following year he lost the power to appoint regional chiefs[lxxxvi]. In 1930 Mwami Musinga was removed from power because of disagreements with the Belgian occupiers and replaced by his son Rudahigwa[lxxxvii]. At this point the Mwami had lost much of his power to lower level chiefs and colonial administrators. The introduction of the Native Tribunals in 1936 finally stripped the Mwami of almost all his judicial power[lxxxviii]. This final shift caused the Mwami to lose most of his power, which was in turn relegated to the Tutsi aristocracy loyal to the colonial authorities. The chiefs who were willing to work with the colonial government would often make great profits, as the chiefs would extract wealth from the people for themselves and for the Belgian Empire[lxxxix].

The 1930's was also a period when the colonial authorities increased their efforts to racialise Hutu and Tutsi identities. The official census of 1933 to 1934 was the first practical measure towards constructing Hutu and Tutsi as distinct racial categories[xc]. In 1935 the Belgian authorities began issuing identity cards to people which declared whether they were Hutu, Tutsi or Twa[xci]. It is often assumed in popular history that the 10 cow rule was the defining feature of who was categorised as Hutu and who was Tutsi, but this is not accurate[xcii]. There were more people classified as Tutsi than the amount of people who could possibly have owned more than 10 cows[xciii]. There seems to have been three yardsticks for deciding who was Hutu and who was Tutsi, these being oral accounts from churches, measurements and physical appearance, and ownership of large herds of cows[xciv]. In this way the Belgian authorities were not completely arbitrary in their categorisation, but rather racialised. In this way theyfroze socio-political distinctions that had previously been fluid and open[xcv]. It was at this time that the colonial authorities constructed the Tutsi people as non-indigenous[xcvi].

From 1941 to 1945 Rwanda went through the worst famine in its history and an estimated 200.000 out of a population of 2 million people died of starvation[xcvii].

Meeting between Belgian colonialist and Rwandan local. Image source

Meeting between Belgian colonialist and Rwandan local. Image source

The 1959 Revolution and independence from Belgium

During the 1950's Hutu people were given more rights by the colonial authorities. This was partly because of Rwanda becoming a mandate under the United Nations (Belgium would still administrate the country). In 1952 Mwami Mutara III Rudahigwa increased the number of Hutu people in his administration, and in 1954 he abolished the ubuhake system which had facilitated the use of Hutu people as forced labour[xcviii]. This came both after pressure from the UN[xcix] and with the emergence of a Hutu elite which countered the Tutsi aristocracy[c]. Many Hutu had elevated their social positions through working abroad (Uganda, Congo), getting an education (through missionaries and colonial authorities), and also through connections to remnants of a northern post-colonial Hutu elite (which only became part of Rwanda after the colonial occupation)[ci].

In 1953 there was localelections for councils who would only be giving advice and had no actual power. The Tutsi came to dominate these councils, especially the higher level ones[cii]. In 1956 Rwanda held national elections, but because representatives were elected indirectly by an electoral college made up of mainly Tutsi chiefs, the result was in favour of Tutsi representatives[ciii]. In 1956 Rudahigwa demanded independence from Belgian colonial rule[civ], and the advisory councils elected in 1953 and 1956 became the parliaments of the post-colonial state[cv]. There was only one problem, in the period between 1956 and 1959 these councils were made up of less than 6% Hutu people[cvi]. All the reforms were limited in scope or in implementation and at the end of the day would never be enough to give Hutu people equal rights in Rwanda.

In 1957 the Mwami presented a report to the UN decolonization mission stating that power needed to be transferred from the colonial authorities to the King of Rwanda and his council, in order to end racial tensions between blacks and whites in the country[cvii]. In response to this report Grégoire Kayibanda and eight other Hutu published the Bahutu Manifesto[cviii]. The manifesto stated that the conflict in Rwanda was not between whites and blacks, but rather the Hutu's struggle from both white colonialists and the Tutsi Hamitic invaders[cix]. A year later the royal court responded through 14 Tutsi aristocrats in a letter titled: “The faithful servants of the Mwami”[cx]. In this letter they rejected any claims to brotherhood between Tutsi and Hutu and argued that the Tutsi people were inherently superior to the Hutu people[cxi]. The Tutsi aristocracy argued that post-colonial Rwanda should return to their pre-colonial traditions, which included the system in which Tutsi ruled over Hutu[cxii].

With equality between the two groups rejected, a group of Hutu intellectuals, led by Grégoire Kayibanda, founded the political party PARMEHUTU (Party for the Movement for Hutu Liberation) in 1959[cxiii]. The local and national election, and the clear rejection by the Tutsi elite of Hutu/Tutsi equality had the effect of forming and cementing a Hutu consciousness and nationalism. The struggle forward was not just an anti-colonial struggle, but also a fight against the national Tutsi elite. PARMEHUTU was a militant party that adhered to revolutionary politics[cxiv].

Several other political parties representing different political perspectives were formed at the same time. The two main Tutsi aligned parties were UNAR (traditionalist and monarchist) and RADER (soft-reformist), and the two main Hutu aligned parties were PARMEHUTU (revolutionary and eventually anti-monarchist) and APROSOMA (started out as a populist party for both Hutu and Tutsi, and became the moderates)[cxv]. PARMEHUTU wanted to mobilise all Hutu people against all Tutsi as they saw the Hutu/Tutsi divide as the defining feature of privilege and power in Rwanda, APROSOMA, on the other hand, wanted to unite poor Hutu people with poor Tutsi in reformist struggle against the country's elite. Some historians argue that APROSOMA failed to understand that Tutsi privilege was not just about wealth, but rather a political and legal privilege that all Tutsi had no matter their material possessions.

On the 25 of July, 1959, Mwami Mutara III Rudahigwa died unexpectedly and without a direct heir[cxvi]. His half-brother Jean-Baptiste Ndahindurwa became the new Mwami three days later, under the assumed name of Kigeli V Ndahindurwa[cxvii]. The appointment of Ndahindurwa as King is referred toas the Mwima coup[cxviii]. Soon after the coup followed violent conflict and confrontation between militants from PARMEHUTU and Tutsi people loyal to the monarchist UNAR party[cxix]. On 1 November a Hutu sub-chief was assaulted by a group of Tutsi youth, an incident that has been cited as the spark that lit the fuse[cxx]. It is estimated that more than 200 Tutsi people were killed in the early violence[cxxi] and many fled the country[cxxii]. Attempts by the Belgian colonial authorities to stop the violence were misguided, and would eventually help usher in the coming “social revolution”[cxxiii]. The 1960 and 1961 legislative elections saw a massive win for PARMEHUTU, and as the monarchy was falling thousands of Tutsi people fled the country[cxxiv]. In 1960 Grégoire Kayibanda became prime minister, and in 1961 the monarchy was abolished and Dominique Mbonyumutwa became the interim president of Rwanda[cxxv]. In 1962 a referendum on the monarchy was held and the monarchists were defeated gaining only 16.8% of the vote[cxxvi].

In 1960 a large amount of Tutsi people, especially the holders of power, fled the country withsome of these people organising themselves into armed groups[cxxvii]. During 1962 – 1964 the armed groups launched several unsuccessful armed assaults into the country from Burundi and Uganda[cxxviii]. The assault led to retaliation from the Hutu-led, Rwandan government against Tutsi civilians. It is estimated that 2.000 people died in 1962 and as many as 10,000 people in 1963[cxxix]. Between 40 – 70 percent of the Tutsi population (140,000 – 250.00) are estimated to have fled the country[cxxx]. Grégoire Kayibanda argued for a policy of segregation between Hutu and Tutsi and stated that they were “two nations in a single state”[cxxxi]. The general elections in 1961 saw PARMEHUTU win an overwhelming victory and Grégoire Kayibanda was sworn in as president of Rwanda[cxxxii]. On July 1, 1962, Rwanda officially declared its independence from Belgium.

The first Republic of Rwanda

The mid 1960's saw increased repression of Tutsi people and opposition parties by PARMEHUTU and Grégoire Kayibanda. The first Republic was strictly a Hutu state as things were now supposed to be the opposite of what it had been during the colonial period. The racial policies of the colonial state continued and the Tutsi were regarded as the foreigners and therefore unsuited for political power[cxxxiii]. In 1964 a concerted effort was made to remove all Tutsi influence from the political arena[cxxxiv]. Yet many Tutsi people remained in relative positions of power and privilege. They dominated both the civil service and the education system[cxxxv].

After the Tutsi political influence had been removed PARMEHUTU turned on the Hutu opposition. During the period 1964 to 1967 political representatives from the APROSOMA party were slowly being removed from any positions of power[cxxxvi]. PARMEHUTU still faced criticism for their handling of education and the lack of employment opportunities. In 1966 there were efforts to increase Hutu participation in the education system, which was still dominated by Tutsi people[cxxxvii]. In 1970 PARMEHUTU, now renamed Democratic Republican Movement (MDR) to get rid of ethnic connotations, institutionalised ethnic quotas in schools and administration[cxxxviii].

Up until the 1970's there was a huge increase in Hutu people with higher education, but there was little employment for the graduates after they finished school. There was no special policy for adequate Hutu representation in employment[cxxxix]. These criticisms against President Kayibanda and the PARMEHUTU government gathered momentum in the early 1970's.

The 1973 coup and the second Republic of Rwanda

The coup of 1973 was triggered largely by unemployed and educated Hutu people[cxl]. Adding to the internal dissatisfaction with Kayibanda's regime, was a massacre by Tutsi people of Hutu people in Burundi in 1972[cxli]. This massacre caused violence and reprisals against Tutsi people in Rwanda, and Hutu intellectuals from the northern part of Rwanda started a campaign to expel all Tutsi people from schools and public administration[cxlii]. On July 5, 1973, Major General Juvénal Habyarimana, who was defence minister in Kayibanda's government, seized power by force. His reasoning for doing so was to quell the general unrest that had gripped the country since 1972[cxliii]. Kayibanda and many of the most powerful people in the country was killed during the coup[cxliv].

During the second republic the Hutu/Tutsi divide was conceptualised from race to ethnicity, thus the Tutsi went from being classified a foreign race to being classified an ethnic minority[clxv]. It was still acknowledged that the Tutsi people came from a position of privilege, but in the second republic they were allowed a limited involvement in politics[cxlvi]. The new regime also set up policies to bring justice and reconciliation between Hutu and Tutsi people. Affirmative action programs and limiting political actions were instituted to increase to amount off Hutu people represented in many previously Tutsi dominated sectors (the Church, schools and employment)[cxlvii]. Justice was in this sense seen as appropriation and redistribution[cxlviii].

President Habyarimana's regime was an authoritarian one, with rigged elections to give the appearance of democracy. The president was always re-elected with more than 98% of the vote and journalism was heavily censored[cxlix]. In 1975 Habyarimana founded the political party, the National Revolutionary Movement for Development, known in French as the Mouvement Révolutionnaire pour le Développement (MRND)[cl]. All Rwandan people had to belong to the party and all other political parties were outlawed after 1978[cli]. At the same the precursor to the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), the Rwandese Alliance for National Unity (RANU)was formed by Rwandan refugees in Nairobi, Kenya[clii].

The Rwandan government would also continue to allocate and use the same identity papers that identified people as Hutu or Tutsi during the colonial period[cliii]. While the representation of Tutsi people increased during Habyarimana's regime, it was with the assumption that they would still give up any idea that they would have a meaningful participation in power[cliv]. Foreign businesses were however exempted from affirmative action policies and they overwhelmingly employed people with a Tutsi background[clv]. Tutsi people would therefore remain relatively privileged in the private sector in Rwanda.

President Juvénal Habyarimana on a state visit in the USA in 1980. Image source

President Juvénal Habyarimana on a state visit in the USA in 1980. Image source

The mid to late 1980s saw a period of economic decline for Rwanda. In 1985 the country was rocked by several corruption scandals leading to the forced resignation of the head of the national bank in April of that same year[clvi]. The country then experienced a severe resource crisis, which was made measurably worse by the sudden and devastating plunge in coffee prices in 1989[clvii]. This caused the Rwandan GDP to fall by 5.9%, down to the level it was in 1983[clviii]. In need of credit to alleviate the economic crisis the Rwandan government appealed to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which in return began the implementation of a Structural Adjustment Program to help the economy[clix]. The program had two main goals, which were to de-subsidise the coffee industry and to get rid of the budget deficits. The program exacerbated the economic crisis, particularly on the ground, and caused further instability and internal unrest.

At the same time external events in neighbouring Burundi and Uganda was affecting Rwanda. The Tutsi refugees in Uganda, who had fled the genocides of 1959, were being persecuted by the Ugandan government in the early 1980s. Discrimination and marginalisation that overshadowed the Rwandan diaspora in Uganda was rife even in the late 1980s[clx]. This would serve to radicalise the Tutsi people living there and spur on the idea that they needed to return to Rwanda and seize control of the state there. In 1988 about 50.000 Hutu people fled from ethnic violence in Burundi to Rwanda[clxi], which radicalised the Hutu people living in Rwanda.

In 1986 the National Resistance Movement (NRM) took power in Uganda, and many of the guerilla fighters who fought for them were the children of Tutsi refugees, most notable was RPF member Paul Kagame[clxii]. By 1987 Kagame was made action chief of military intelligence in Uganda[clxiii]. It is debated whether he and other leaders of the RPF joined the NRM's armed uprising to gain weapons and experience, or if their decision to invade Rwanda arose after they became disillusioned by the discrimination against Rwandan people living in Uganda[clxiv]. However, in October 1990, supported with arms and material from Uganda, the RPF began their armed invasion of Rwanda[clxv].

Civil war and Genocide

The initial part of the RPF invasion was a disaster. The rebels experienced several defeats against the Rwandan army, and RPF soldiers were scattered all over the northern part of Rwanda[clxvi]. This caused Kagame to interrupt his military training in the United States of America and return to Rwanda to lead the RPF forces[clxvii]. In1991 the RPF experienced several victories on the battlefield, but failed to translate those victories into longer term strategic wins. The cause of this was that the local population, of mostly Hutu farmers, did not see the RPF as liberators and they would flee as soon as the rebels approached[clxviii]. In 1993 about 950.000 Hutu people were internally displaced[clxix].

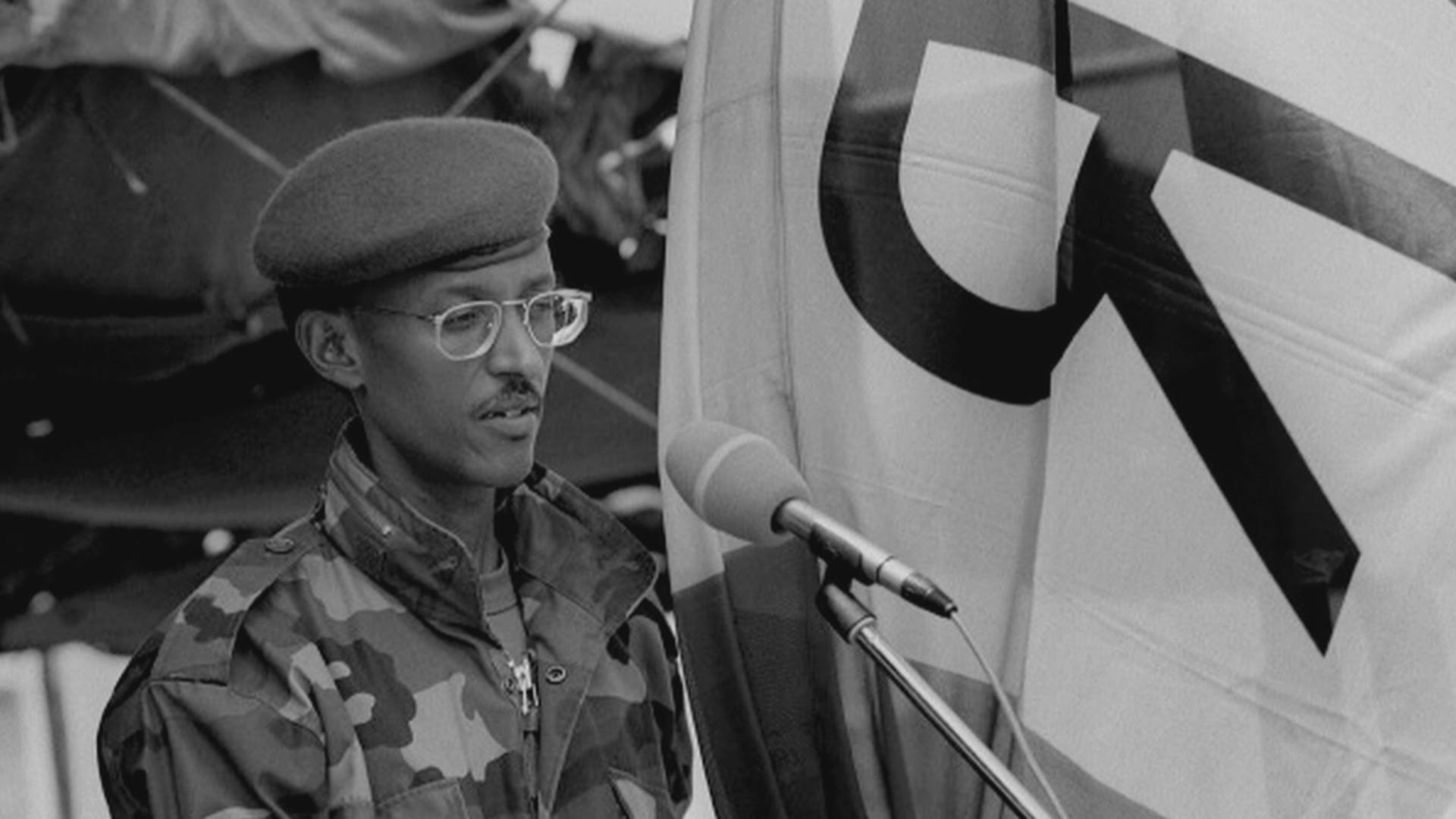

Paul Kagame in 1994. Image source

Paul Kagame in 1994. Image source

The RPF invasion of Rwanda meant an immediate end to the attempts of reconciliation which the regime of President Habyarimana had begun[clxx]. This meant that the Rwandan state turned its politics from one of national unification towards one of Hutu power. At the same time refugees from the north brought pressure on a Rwandan government already unpopular because of the economic decline of the previous years. The internal Hutu opposition also began using the spectre of an oppressive Tutsi regime, like the one before 1959, as a tool for gaining power and unseating President Habyarimana. Proponents of Hutu power brought back the colonial myth that Tutsi people were not indigenous to Rwanda[clxxi]. In 1992 a Hutu power youth militia called the Interahamwe was started by the ruling party[clxxii]. Both the Interahamwe and the Rwandan government army were supplied with weapons and materials by the French[clxxiii].

Several massacres of Tutsi people were carried out by Rwandan government security agents as retaliations against the advancing RPF. Between 1990 and 1993, an estimated 3.000 thousand Tutsi people were been killed by both government agents and civilian Hutu power groups[clxxiv]. The ongoing civil war was feeding and deepening the historical divide between Hutu and Tutsi people[clxxv]. The Rwandan state was losing the war against the RPF and this was causing a great strain on the regime. There was a split within the Hutu political elite between “moderates”, who wanted to negotiate with RPF, and a faction called “power”, which promoted Hutu power[clxxvi].

By February 1993 it was estimated that about one million Rwandans, or almost 15% of the population, were internally displaced[clxxvii]. This created huge refugee camps in the areas still controlled by the government. Added to this were the Hutu refugees who had fled political violence in neighbouring Burundi. Several political parties established youth wings in 1992 and 1993. These youth wings would quickly get recruits from the vast amount of refugees and after the February 1993 RPF offensive many of the youth organisations turned into armed militias[clxviii]. This happened partly because, in an effort to strengthen the government’s war effort, President Habyarimana began arming the civilian population[clxxix]. These armed civilian “self defence” units would later become the core part of the civilian participation in the 1994 genocide[clxxx].

Added to all this strife the Rwandan government and the RPF signed a peace agreement in Arusha, Tanzania, which excluded proponents of Hutu power from the new political order[clxxxi]. President Habyarimana turned against the agreement, and the opposition parties who had signed it was accused of betraying Rwanda and to opening the door for Tutsi power[clxxxii]. After the Rwandan prime minister was killed together with the ten UN soldiers guarding her, the UN (with the USA in charge) decided to pull out all but 270 of the UN soldiers stationed in the country[clxxxiii]. This was supposed to be a signal to the Rwandan government that they needed to implement the Arusha agreement or the UN would let the RPF take over Rwanda.

On the 6 April, 1994, President Habyarimana's plane was shot down and later that day the prime minister, Agathe Uwilingiyimana, was murdered[clxxxiv]. These assassinations confirmed all suspicions of what would happen to Hutu people if the Tutsi people ever came to power again. This was the spark which would ignite an extremely volatile situation and start an all out genocide of Tutsi people in Rwanda. Between April and July 1994 more than 800,000 Tutsi people were killed, including thousands of Hutu people who was part of the opposition or refused to take part in the killings[clxxxv].

Kigali memorial centre for the victims of the 1994 genocide. Image source

Kigali memorial centre for the victims of the 1994 genocide. Image source

In July 1994 the RPF occupied Kigali and took over power in Rwanda, with Paul Kagame as the de facto leader, and over the span of the next two weeks more than two million Hutu people fled the country[clxxxvi]. Most of them fled to the Democratic Republic of Congo (then called Zaire) or to Tanzania[clxxxvii]. In the Democratic Republic of Congo the refugees settled in the Kivu province which already had a large Banyarwanda speaking population, most of whom settled there after the internal conflicts in the immediate aftermath of Mwami Kigeri IV Rwabugiri[clxxxviii].

RPF in power and military conflicts in the Democratic Republic of Congo

The huge influx of Rwandan refugees pouring into the Kivu province of the DRC was creating massive internal disruptions. Hutu genocidares perceived enemies everywhere in Kivu, and Tutsi armed forces affiliated with the RPF were in turn hunting down killers from the genocide in Rwanda[clxxxix]. Civilians who were not involved with either side were caught in the middle of this violence, which in turn caused a greater militarisation of civilian life in Kivu[cxc]. This militarisation was a leading cause of the First Congo War, and an invasion by the RPF which eventually led to the fall of the then dictator of the DRC Mobutu Sésé Seko[cxci]. This also saw the beginning of occupation of large areas of the DRC and wide scale looting of its national mineral resources by Rwanda and other African countries. This conflict is sometimes referred to as the first and second Congo Wars. Some describe it as one conflict, named the Great African War. By 2004 millions of people died as a result of the war.

Rwanda itself was greatly transformed by the 1994 genocide and the RPF coming to power. The first issue to deal with for the new regime was to exact justice on the perpetrators of the genocide. This would prove a difficult ordeal as the genocide in Rwanda was one of mass participation by the civilian population. The Rwandan government estimated that there were millions of Rwandan people who actively participated in the killings[cxcii]. To dispense justice make-shift courts, called Gacaca courts, were set up all around the country to facilitate community inspired justice against local perpetrators of the genocide. By the end of 2006 818,564 suspects had been accused of various crimes in the Gacaca courts[cxciii]. In 2007 the trial phase began and over the next three and a half years 423,557 people were tried[cxciv].

The teaching of history was deeply affected by the genocide, and for the next 15 years teachers were only allowed to teach a narrative of national unity[cxcv]. This meant that any historical period that emphasised internal conflict and division was underplayed in historical teaching[cxcvi]. The political language also changed and people could no longer speak about a Hutu or Tutsi identity. The categories in which the 1994 genocide came to be understood were refugees, returnees, victims, survivors and perpetrators[cxcvii]. This was an attempt to completely eradicate Hutu and Tutsi as political identities.

The narrative of Rwanda and the RPF-led government between 2005 and 2015 is a contested one. The country was lauded for its impressive Growth Domestic Product (GDP) growth of 8% in 2005, yet the country had limited success in its human development and poverty reduction programs[cxcviii]. There was, however, a reduction in poverty levels of 12% from 2005 to 2010[cxcix]. There is no doubt that there was some improvement in the material life of the average Rwandan during this period. In 2000 Paul Kagame offically became the President of Rwanda, but he has been criticised for having an authoritarian style and some claim that he has set himself up for being president for life[cc]. He was also accused of assassinating members of the political opposition, the most notable incident being the killing of ex-intelligence head Patrick Karegeya in South Africa in 2014[cci].

[i] Jennifer Gaugler, “Selective Visibility: Governmental Policy and the Changing Cultural Landscape of Rwanda” in ARCC 2013 | The Visibility of Research Policy: Educating Policymakers, Practitioners, and the Public. Page 376. ↵

Endnotes

[ii] Ibid. Page 377. ↵

[iii] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 2007). Page xliii. ↵

[iv] Ibid. Page xxviii. ↵

[v] Ibid. Page 85. ↵

[vi] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). ↵

[vii] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J. Page 32. ↵

[viii] David Booth and Frederick Golooba-Mutebi, “Developmental patrimonialism? The case of Rwanda”, Afr Aff (Lond) (2012) 111 (444): 379-403. doi: 10.1093/afraf/ads026 First published online: May 16, 2012. Page 385. ↵/strong>

[ix] Catharine Newbury, “Ethnicity and the Politics of History in Rwanda”, Africa Today, Vol. 45, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1998), pp. 7-24. Accessed June 26, 2016, doi: : http://www.jstor.org/stable/. Page 9. ↵

[x] Peter Uvin, 1999, “Ethnicity and Power in Burundi and Rwanda: Different Paths to Mass Violence” in Comparative Politics, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Apr., 1999), pp. 253-271 Published by: Comparative Politics, Ph.D. Programs in Political Science, City University of New York. Page 254. ↵

[xi] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 42. ↵

[xii] Jan Vansina, Antecedents to Modern Rwanda: The Nyiginya Kingdom, (Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2004). Page 16. ↵

[xiii] Jennifer Gaugler, “Selective Visibility: Governmental Policy and the Changing Cultural Landscape of Rwanda” in ARCC 2013 The Visibility of Research Policy: Educating Policymakers, Practitioners, and the Public. Page 376. ↵

[xiv] Ibid. ↵

[xv] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 2007). Page 160. ↵

[xvi] Jan Vansina, Antecedents to Modern Rwanda: The Nyiginya Kingdom, (Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2004). Page 18. ↵

[xvii] Jennifer Gaugler, “Selective Visibility: Governmental Policy and the Changing Cultural Landscape of Rwanda” in ARCC 2013 The Visibility of Research Policy: Educating Policymakers, Practitioners, and the Public. Page 376. ↵

[xviii] Peter Uvin, 1999, “Ethnicity and Power in Burundi and Rwanda: Different Paths to Mass Violence” in Comparative Politics, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Apr., 1999), pp. 253-271 Published by: Comparative Politics, Ph.D. Programs in Political Science, City University of New York. Page 255. ↵

[xix] Jennifer Gaugler, “Selective Visibility: Governmental Policy and the Changing Cultural Landscape of Rwanda” in ARCC 2013 The Visibility of Research Policy: Educating Policymakers, Practitioners, and the Public. Page 376. ↵

[xx] Peter Uvin, 1999, “Ethnicity and Power in Burundi and Rwanda: Different Paths to Mass Violence” in Comparative Politics, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Apr., 1999), pp. 253-271 Published by: Comparative Politics, Ph.D. Programs in Political Science, City University of New York. Page 255. ↵

[xxi] Ibid. ↵

[xxii] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 53. ↵

[xxiii] Jan Vansina, Antecedents to Modern Rwanda: The Nyiginya Kingdom, (Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2004). Page 18. ↵

[xxiv] Jean-Pierre Chrétien and Scott Straus, The Great Lakes of Africa: Two Thousand Years of History, (Zone Books: Cambridge, 2006). Page 58. ↵

[xxv] Jan Vansina, Antecedents to Modern Rwanda: The Nyiginya Kingdom, (Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2004). Page 22. ↵

[xxvi] Ibid. Page 23. ↵

[xxvii]Peter Uvin, 1999, “Ethnicity and Power in Burundi and Rwanda: Different Paths to Mass Violence” in Comparative Politics, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Apr., 1999), pp. 253-271 Published by: Comparative Politics, Ph.D. Programs in Political Science, City University of New York. Page 255. ↵

[xxviii] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 61. ↵

[xxix] Jan Vansina, Antecedents to Modern Rwanda: The Nyiginya Kingdom, (Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2004). Page 36. ↵

[xxx] Jean-Pierre Chrétien and Scott Straus, The Great Lakes of Africa: Two Thousand Years of History, (Zone Books: Cambridge, 2006). Page 77. ↵

[xxxi] Ibid. Page 88. ↵

[xxxii] Ibid. Page 127. ↵

[xxxiii] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 2007). Page 32. ↵

[xxxiv] Jan Vansina, Antecedents to Modern Rwanda: The Nyiginya Kingdom, (Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2004). Page 31. ↵

[xxxv] Ibid. ↵

[xxxvi] Jean-Pierre Chrétien and Scott Straus, The Great Lakes of Africa: Two Thousand Years of History, (Zone Books: Cambridge, 2006). Page 113. ↵

[xxxvii] Ibid. Page 188. ↵

[xxxviii] R. O. Collins & J. M. Burns. 2007. A History of Sub-Saharan Africa, Cambridge University Press. Page 124. ↵

[xxxix] Peter Uvin, 1999, “Ethnicity and Power in Burundi and Rwanda: Different Paths to Mass Violence” in Comparative Politics, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Apr., 1999), pp. 253-271 Published by: Comparative Politics, Ph.D. Programs in Political Science, City University of New York. Page 254. ↵

[xl] Jennifer Gaugler, “Selective Visibility: Governmental Policy and the Changing Cultural Landscape of Rwanda” in ARCC 2013 The Visibility of Research Policy: Educating Policymakers, Practitioners, and the Public. Page 377. ↵

[xli] Ibid. ↵

[xlii] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 2007). Page 80. ↵

[xliii] Ibid. Page 162. ↵

[xliv] Peter Uvin, 1999, “Ethnicity and Power in Burundi and Rwanda: Different Paths to Mass Violence” in Comparative Politics, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Apr., 1999), pp. 253-271 Published by: Comparative Politics, Ph.D. Programs in Political Science, City University of New York. Page 255. ↵

[xlv] Jan Vansina, “Historical Tales (Ibiteekerezo) and the History of Rwanda”, History in Africa, Vol. 27 (2000), pp. 375-41. Cambridge University Press. Page 377. ↵

[xlvi] Jan Vansina, Antecedents to Modern Rwanda: The Nyiginya Kingdom, (Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2004). Page 45. ↵

[xlvii] Ibid.. ↵

[xlviii] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 62. ↵

[xlix] Jan Vansina, “Historical Tales (Ibiteekerezo) and the History of Rwanda”, History in Africa, Vol. 27 (2000), pp. 375-41. Cambridge University Press. Page 414. ↵

[l] Jan Vansina, Antecedents to Modern Rwanda: The Nyiginya Kingdom, (Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2004). Page 11. ↵

[li] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 2007). Page xxvii. ↵

[lii] Jan Vansina, Antecedents to Modern Rwanda: The Nyiginya Kingdom, (Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2004). Page 43. ↵

[liii] Ibid. Page 44. ↵

[liv] Ibid. Page 196. ↵

[lv] Peter Uvin, 1999, “Ethnicity and Power in Burundi and Rwanda: Different Paths to Mass Violence” in Comparative Politics, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Apr., 1999), pp. 253-271 Published by: Comparative Politics, Ph.D. Programs in Political Science, City University of New York. Page 254. ↵

[lvi] Jan Vansina, “Historical Tales (Ibiteekerezo) and the History of Rwanda”, History in Africa, Vol. 27 (2000), pp. 375-41. Cambridge University Press. Page 413. ↵

[lvii] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 2007). Page xliii. ↵

[lviii] Ibid. ↵

[lix] Ibid. ↵

[lx] Ibid. ↵

[lxi] Jan Vansina, Antecedents to Modern Rwanda: The Nyiginya Kingdom, (Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2004). Page 41. ↵

[lxii] Jennifer Gaugler, “Selective Visibility: Governmental Policy and the Changing Cultural Landscape of Rwanda” in ARCC 2013 The Visibility of Research Policy: Educating Policymakers, Practitioners, and the Public. Page 377. ↵

[lxiii] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 2007). Page xliii. ↵

[lxiv] Ibid. ↵

[lxv] Ibid. ↵

[lxvi] Ibid. Page xxvii. ↵

[lxvii] Ibid. ↵

[lxviii] Ibid. Page 69. ↵

[lxix] Helen M. Hintjens, “When identity becomes a knife,Reflecting on the genocide in Rwanda”, Ethnicities March 2001 vol. 1 no. 1 25-55. Page 27. ↵

[lxx] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 2007). Page xxviii. ↵

[lxxi] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 72. ↵

[lxxii] Ibid. ↵

[lxxiii] Ibid. ↵

[lxxiv] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 2007). Page 69. ↵

[lxxv] Ibid. ↵

[lxxvi] Ibid. Page 85. ↵

[lxxvii] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 24. ↵

[lxxviii] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 2007). Page 85. ↵

[lxxix] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 34. ↵

[lxxx] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 2007). Page 85. ↵

[lxxxi] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 89. ↵

[lxxxii] Ibid. Page 27. ↵

[lxxxiii] Ibid. Page 34. ↵

[lxxxiv] Ibid. ↵

[lxxxv] Ibid. Page 35. ↵

[lxxxvi] Ibid. Page 90. ↵

[lxxxvii] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 2007). Page 69. ↵

[lxxxviii] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 91. ↵

[lxxxix] Ibid. Page 97. ↵

[xc] Ibid. Page 98. ↵

[xci] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 2007). Page xxvii. ↵

[xcii] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 98. ↵

[xciii] Ibid. ↵

[xciv] Ibid. Page 99. ↵

[xcv] Ibid. ↵

[xcvi] Ibid. ↵

[xcvii] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 2007). Page xxvii. ↵

[xcviii] Ibid. Page xxix. ↵

[xcix] Ibid. ↵

[c] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 106. ↵

[ci] Ibid. ↵

[cii] Ibid. Page 115. ↵

[ciii] Ibid. ↵

[civ] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 2007). Page xxvii. ↵

[cv] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 115. ↵

[cvi] Ibid. ↵

[cvii] Ibid. Page 116. ↵

[cviii] Ibid. ↵

[cix] Ibid. ↵

[cx] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J. Page xxix. ↵

[cxi] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 118. ↵

[cxii] Ibid. ↵

[cxiii] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J.) Page xxix. ↵

[cxiv] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 119. ↵

[cxv] Ibid. Page 123. ↵

[cxvi] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J.) Page xxix. ↵

[cxvii] Ibid. ↵

[cxviii] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 123. ↵

[cxix] Ibid. ↵

[cxx]Catharine Newbury, “Ethnicity and the Politics of History in Rwanda”, Africa Today, Vol. 45, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1998), pp. 7-24. Accessed June 26, 2016, doi: : http://www.jstor.org/stable/. Page 13. ↵

[cxxi] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 123. ↵

[cxxii] Peter Uvin, 1999, “Ethnicity and Power in Burundi and Rwanda: Different Paths to Mass Violence” in Comparative Politics, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Apr., 1999), pp. 253-271published by: Comparative Politics, Ph.D. Programs in Political Science, City University of New York. Page 256. ↵

[cxxiii] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 123. ↵

[cxxiv] Peter Uvin, 1999, “Ethnicity and Power in Burundi and Rwanda: Different Paths to Mass Violence” in Comparative Politics, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Apr., 1999), pp. 253-271 Published by: Comparative Politics, Ph.D. Programs in Political Science, City University of New York. Page 256. ↵

[cxxv] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J.) Page xxx. ↵

[cxxvi] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 125. ↵

[cxxvii] Peter Uvin, 1999, “Ethnicity and Power in Burundi and Rwanda: Different Paths to Mass Violence” in Comparative Politics, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Apr., 1999), pp. 253-271 Published by: Comparative Politics, Ph.D. Programs in Political Science, City University of New York. Page 256. ↵

[cxxviii] Ibid. ↵

[cxxix] Ibid. ↵

[cxxx] Ibid. ↵

[cxxxi] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 127. ↵

[cxxxii] Ibid. ↵

[cxxxiii] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 135. ↵

[cxxxiv] Ibid. ↵

[cxxxv] Ibid. ↵

[cxxxvi] Ibid. ↵

[cxxxvii] Ibid. ↵

[cxxxviii] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J.) Page xxx. Is this the page number? ↵

[cxxxix] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 136. ↵

[cxl] Ibid. Page 137. ↵

[cxli] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J.) Page xxx. ↵

[cxlii] Ibid. ↵

[cxliii] Ibid. ↵

[cxliv] Peter Uvin, 1999, “Ethnicity and Power in Burundi and Rwanda: Different Paths to Mass Violence” in Comparative Politics, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Apr., 1999), pp. 253-271 Published by: Comparative Politics, Ph.D. Programs in Political Science, City University of New York. Page 257. ↵

[cxlv] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 138. ↵

[cxlvi] Ibid. ↵

[cxlvii] Ibid. ↵

[cxlviii] Ibid. Page 139. ↵

[cxlix] Peter Uvin, 1999, “Ethnicity and Power in Burundi and Rwanda: Different Paths to Mass Violence” in Comparative Politics, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Apr., 1999), pp. 253-271 Published by: Comparative Politics, Ph.D. Programs in Political Science, City University of New York. Page 257. ↵

[cl] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J.) Page xxx. ↵

[cli] Ibid. ↵

[clii] Ibid. ↵

[cliii] Peter Uvin, 1999, “Ethnicity and Power in Burundi and Rwanda: Different Paths to Mass Violence” in Comparative Politics, Vol. 31, No. 3 (Apr., 1999), pp. 253-271 Published by: Comparative Politics, Ph.D. Programs in Political Science, City University of New York. Page 257. ↵

[cliv] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 140. ↵

[clv] Ibid. ↵

[clvi] Ibid. Page 151. ↵

[clvii] Ibid. Page 147. ↵

[clviii] Ibid. Page 148. ↵

[i] text here... ↵

[clix] Ibid. ↵

[clx] Ibid. 174. ↵

[clxi] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J. Page xxxi. ↵

[clxii] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 173. ↵

[clxiii] Ibid. ↵

[clxiv] Ibid. ↵

[clxv] Ibid. Page 183. ↵

[clxvi] Ibid. Page 186. ↵

[clxvii] Ibid. ↵

[clxviii] Ibid. ↵

[clxix] Ibid. Page 187. ↵

[clxx] Ibid. Page 185. ↵

[clxxi] Ibid. Page 190. ↵

[clxxii] Ibid. Page 191. ↵

[clxxiii] Ibid. Page 254. ↵

[clxxiv] Ibid. Page 192. ↵

[clxxv] Ibid. Page 202. ↵

[clxxvi] Ibid. Page 203. ↵

[clxxvii] Ibid. ↵

[clxxviii] Ibid. Page 204. ↵

[clxxix] Ibid. Page 206. ↵

[clxxx] Ibid. ↵

[clxxxi] Ibid. Page 212. ↵

[clxxxii] Ibid. ↵

[clxxxiii] Ibid. Page 213. ↵

[clxxxiv] Ibid. Page 216. ↵

[clxxxv] Aimable Twagilimana, Historical Dictionary of Rwanda, (Metuchen, N.J. Page 32. ↵

[clxxxvi] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 234. ↵

[clxxxvii] Ibid. ↵

[clxxxviii] Ibid. Page 248. ↵

[clxxxix] Ibid. Page 256. ↵

[cxc] Ibid. ↵

[cxci] Ibid. ↵

[cxcii] Ibid. Page 266. ↵

[cxciii] Bert Ingelaere, "Traditional Justice and Reconciliation after Violent Conflict: Learning from African Experiences", (2008), Extracted from Traditional Justice and Reconciliation after Violent Conflict: Learning from African Experiences. International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance 2008. Page 40. ↵

[cxciv] Ibid. Page 43. ↵

[cxcv] Antoon De Baets, “Post-Conflict Historical Education Moratoria: A Balance, World Studies in Education, Vol. 16, No.1, 2015. James Nicholas Publishers: University of Groeningen. Page 14. ↵

[cxcvi] Ibid. ↵

[cxcvii] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2002). Page 266. ↵

[cxcviii] David Booth and Frederick Golooba-Mutebi, “Developmental patrimonialism? The case of Rwanda”, Afr Aff (Lond) (2012) 111 (444): 379-403. doi: 10.1093/afraf/ads026 First published online: May 16, 2012. Page 385. ↵

[cxcix] Ibid. ↵

[cc] Gabriel Gatehouse, “Patrick Karegeya: Mysterious death of a Rwandan exile”, (2014), in BBC News 26 March 2014. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-. (Accessed the 18.07.2016). ↵

[cci] Ibid. ↵