Simon van der Stel was born on 14 October 1639 to parents Adrian van der Stel and Maria Leviens. The couple were en route to Mauritius when Maria gave birth to Simon aboard the ship le Cappel. Van der Stel’s father duly became the first Dutch Commander of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in Mauritius. [1] His mother Maria was the daughter of Hendrik Lievens of Batavia (present-day Jakarta) and Monica of the Coromondel, who is also known as Monica van Goa, a former slave woman of Indian descent. At the time it was common for Company men working in Batavia to take wives of non-European descent. Simon van der Stel thus became the first person not born in Europe and born of mixed parentage to be appointed Commander and eventually Governor of the Cape.

While Adrian van der Stel’s governorship in Mauritius only lasted five years, the family remained in Mauritius for a total of seven years. Shortly after relocating to Dutch Ceylon, Simon’s father died in battle in the service of the Company and the family once again relocated to Batavia. [2] There is little recorded concerning the early years of Simon’s life until he re-emerges in the records when, at the age of twenty, he moved to Holland and married a young woman by the name of Johanna Jacoba Six. Johanna was the daughter of prominent VOC member, Willem Six. Simon and Johanna had six children together but their marriage was allegedly an unhappy one.

On 12 October 1679 Van der Stel arrived at the Cape where he took up the post of VOC Commander of the Cape. It is believed that he managed to obtain this post through the influence of his relative and then mayor of Amsterdam, Joan Huydecoper van Maarsseveen. While at the Cape, Van der Stel and his four sons initially resided in the old Governor’s house before relocating to their private quarters at the Castle in May of 1680. While Van der Stel’s wife, Johanna, remained in the Netherlands, her sister Cornelia Six joined Van der Stel and the family in the Cape. In 1685 Commissioner of the VOC Hendrik Adriaan van Rheede visited the Cape for three months and during this trip granted Van der Stel the title to a farm that Van der Stel duly named ‘Constantia’, to honour the memory of Van Rheede’s daughter. A variety of vineyards were soon laid out on this land and a labour force of slaves worked the harvest. While it is believed that by this point Simon and his wife Johanna had become estranged, she continued to send furnishings and various works of art to fit out the Governor's Residence at Groot Constantia.

During his reign as Commander of the Cape, Van der Stel was responsible for the initial rapid burst of expansion beyond the skirts of Table Mountain. The colony had spread to the Stellenbosch, Drakenstein, Paarl, Franschoek, Tygerberg and Wagenmakers Vallei areas. This territorial expansion had become necessary to facilitate the settlement of a new class of independent farmers – the Freeburghers – who were required to provide the Company with wheat and vegetables. As early as the 1980s Simon van der Stel was faced with the difficult task of meeting the Company’s meat consumption requirement of 3 000 to 4 000 sheep. In order to do so, he focused on building up the Company’s own holdings of cattle and sheep. In the past the Company had been solely reliant on trade with local Khoikhoi groups to acquire livestock and meat. Furthermore, Van der Stel intensified his efforts to obtain cattle and sheep from indigenous groups in the most destructive of manners. In 1693, Chainouqua Captain Dorha (known to the Dutch as Klaas) refused to supply the Company with livestock, triggering Van der Stel to authorise a full-scale attack on Dorha’s kraal through an armed force of 200 soldiers and Freeburghers. [3] The raid saw Dorha captured, many of his followers killed and virtually all of his livestock stolen. Livestock raids similar to the above became commonplace under the administration of Simon van der Stel. In his time as Commander of the Cape, Van der Stel had overseen over forty trading expeditions and as early as 1680 the injurious effects of the livestock trade on the Khoikhoi had been felt.

Somewhat paradoxically, Van der Stel was determined to prohibit the Freeburghers themselves from trading directly with neighbouring Khoikhoi groups. He believed that if the colonists were allowed unhindered access to Khoikhoi livestock they would strip the Khoikhoi of their livestock altogether and destroy the source of supply. Furthermore, there was a risk that these trading activities would push the prices of livestock up drastically. For these reasons, under Van der Stel, the livestock trade was to be left to the Company alone and closed to Freeburgher groups. Those who were found guilty of trading illegally with Khoikhoi groups were met with beatings, branding and banishment. According to Van der Stel, the Freeburghers ‘were nothing but lazy idlers who would indulge in illicit trade with the Khoikhoi and make insatiable demands for land.’ [4]

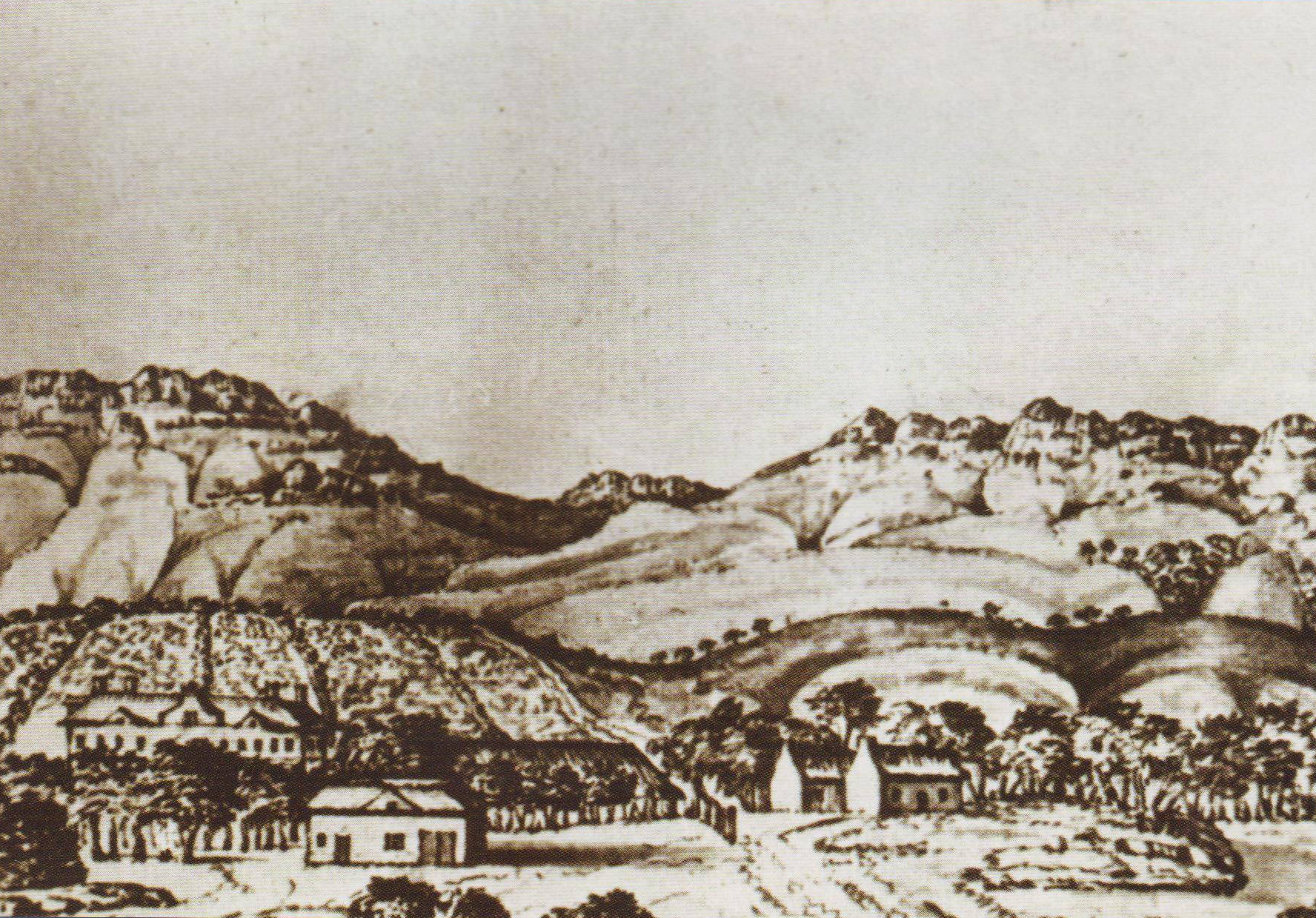

Sketch by de Stade was created circa 1710 and is the earliest known representation of the original Constantia herenhuis and the ground surrounding it. (Source: First Fifty Years: Collating Cape of Good Hope Records)

Sketch by de Stade was created circa 1710 and is the earliest known representation of the original Constantia herenhuis and the ground surrounding it. (Source: First Fifty Years: Collating Cape of Good Hope Records)

In August of 1685, Van der Stel led the first successful European expedition to the Namaqualand region (an area extending from the present day Northern Province in South Africa into neighbouring Namibia) in search of the area’s copper potential. En-route Van der Stel encountered a total of eight or nine Namaqua Khoikhoi kraals under Captain Noncé and did much to alienate and create animosity amongst them, most notably through his attempts to assert Company authority over them. In the official journal of his expedition, Van der Stel notes:

‘After that he presented them with a little brandy, with which they made merry, dancing, singing and shouting in a very queer fashion, resembling nothing so much as a herd of yearling calves just turned out of the cowshed. It was undoubtedly, as they themselves confessed, the only happy day they had had all their lives… [a]ll this passed off very decently, considering that they are savages ... and when the comedy was ended the feast duly began.’ [5]

During his time in command, Van der Stel was also responsible for the building of the ‘new’ Slave Lodge, situated at the present Slave Lodge in Adderley Street Cape Town. The Slave Lodge housed Company slaves as well as a ‘slave school’, which all ‘slave children’ belonging to the Company were compelled to attend until the age of 12. Van der Stel was very involved in the everyday workings of the Slave Lodge School and it is recorded that during the Christmas season he arranged treats and cakes for the schoolchildren.

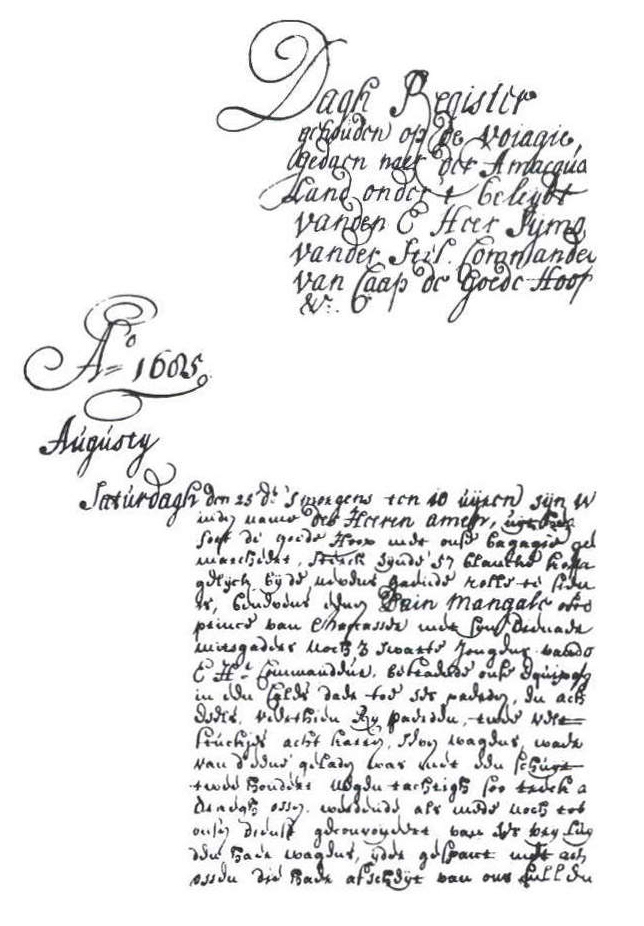

The first page of the 1685 diary of Simon van der Stel. The text describes the departure from the Cape to Namaqualand on 25 August and lists the number of people in the party and their provisions. From Waterhouse (1932)

The first page of the 1685 diary of Simon van der Stel. The text describes the departure from the Cape to Namaqualand on 25 August and lists the number of people in the party and their provisions. From Waterhouse (1932)

The settlement of the French Huguenots at the Cape between the years 1688 and 1689 has been deemed by some as ‘the greatest event of Van der Stel’s period of office’. [6] Van der Stel set aside land for Huguenot settlement in Franschhoek ('French corner') and Drakenstein (present day Paarl), and gave orders for the French to be interspersed with the other burghers. His reasoning for this integration was so 'that they could learn our language and morals, and be integrated with the Dutch nation'. Van der Stel himself however was somewhat distrustful of the French, urging them to become assimilated into the Dutch way of life. This stance should be understood within the context that notwithstanding his mixed ancestry, Simon van der Stel was socialised and educated into a Dutch identity that was strongly nationalistic. Thus when the French resisted and lobbied for their own church, which the Heren XVII (the directors of the VOC) granted them on 6 December 1690, he described the French as ‘the most ungrateful people on the face of the earth’. [7] This was not the only occasion in which the views of Van der Stel and those of the Heren clashed. The Heren XVII had previously strongly criticized the harsh punishments handed down by Van der Stel to those found guilty of illegally procuring livestock from Khoikhoi groups. The tension between Van der Stel and his distant directors was evident in the words of wisdom he handed down to his son, Willem Adriaan, who eventually succeeded him. He warned Willem not to ‘pay too much attention to the instructions of visiting Commissioners, since they were not as well informed as the local authorities.’ [8]

In the waning years of his governorship, Van der Stel’s popularity in the eyes of both the Company and the Freeburghers had begun to diminish. Many of the Dutch colonists believed that he was no longer acting in their best interests, while others claimed that his farm at Constantia was taking precedence ‘over his duties as Governor’. [9] By 1696 Van der Stel had resigned and was succeeded by his son, Willem Adriaan Van der Stel, who arrived with his family on the 23 of January 1699. Thus on the 11 February 1699, having served 20 years in office, Simon van der Stel handed over the reins to his son Willem Adriaan. Van der Stel’s three other sons had all, at one time or another, visited him in South Africa. Frans ‘de jonker’ had become a farmer in the Cape, Adrian had become governor of Ambonia and Cornelis was one of the 352 men aboard the Ridderschap which disappeared off the west coast of Australia in 1694 and was never seen again.

The last years of Simon van der Stel’s life were lonely, without his family at the Cape. By 1712 he had become increasingly ill and eventually died on 24 of June. From his deathbed, Van der Stel shakily signed emancipation papers for many of the people on his slaveholding, including Christina of the Canary Islands who at the time was described as being 28 years old, conversant with Dutch and baptised, all requisites for emancipation during the Dutch colonial period at the Cape. Whether Van der Stel left Christina money is not known, however, in 1717 Christina became the owner of the property Stellenberg. Speculation abounds that she named the property after Van der Stel. It is possible that this young woman nursed Van der Stel during his terminal stage. After Van der Stel’s death his Constantia estate was divided into two portions, namely Great and Little Constantia and sold ‘for the benefit of his heirs’. [10] In accordance with his will 60 people noted as his ‘personal slaves’ and a further 14 ‘farm slaves’, were freed from enslavement. [11] This was a final gesture to enslaved people from a man who carried the legacy of slavery through his maternal bloodline.

Endnotes

[1] Diemont, Marius. Rogues to Riches: The fortunes of Olof Bergh and the van der Stels (Hermanus: Penstock Publishing, 2012) ↵

[2] Spilhaus, M. Whiting. Company’s Men (Cape Town: John Malherbe Pty Ltd, 1973). ↵

[3] N. Penn, The Forgotten Frontier: Colonist and Khoisan on the Cape’s Northern frontier in the Eighteenth Century (Cape Town: Ohio University Press, 2005), p.28. ↵

[4] N. Penn, The Forgotten Frontier: Colonist and Khoisan on the Cape’s Northern frontier in the Eighteenth Century (Cape Town: Ohio University Press, 2005), p.28. ↵

[5] G. Waterhouse(ed), Simon van der Stel’s journal of his expedition to Namaqualand 1685-6 (Dublin: Hodges, Figgis & Co,1932) p. 128, p. 134-135. ↵

[6] Marius Diemont, Rogues to Riches: The fortunes of Olof Bergh and the van der Stels (Hermanus: Penstock Publishing, 2012) p. 24. ↵

[7] Marius Diemont, Rogues to Riches: The fortunes of Olof Bergh and the van der Stels (Hermanus: Penstock Publishing, 2012) p. 60. ↵

[8] N. Penn, The Forgotten Frontier: Colonist and Khoisan on the Cape’s Northern frontier in the Eighteenth Century (Cape Town: Ohio University Press, 2005), p.28. ↵

[9] Marius Diemont, Rogues to Riches: The fortunes of Olof Bergh and the van der Stels (Hermanus: Penstock Publishing, 2012) p. 63. ↵

[10] Marius Diemont, Rogues to Riches: The fortunes of Olof Bergh and the van der Stels (Hermanus: Penstock Publishing, 2012) p. 63. ↵

[11] Mountain, Alan. An Unsung Heritage, Perspectives on Slavery (Claremont: David Philip Publishers, 2004) p.158 ↵