Ernest Cole was born on 21 March 1940 as Ernest Levi Tsoloane Kole, in Eersterust, Pretoria. He left school when Bantu Education was introduced, and unsuccessfully attempted to complete his Matric (Grade 12) via correspondence through Wolsey Hall, Oxford, due to financial constraints.

Cole therefore went to search for a job, but was hindered by his lack of matriculation and by the laws governing South Africa at that time. In terms of these laws Cole was defined as an “unskilled labourer” who could only work as a messenger, tea-maker or floor sweeper. His break came when he was employed as an assistant to a Chinese studio photographer. This is where he obtained basic knowledge of photography, and an old Yashika twin lens reflex camera.

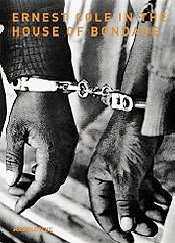

Figure 1. ‘House of Bondage’ book cover. A series of photographic essays by Ernest Cole. Random House publishers. Source: amazon.com

Figure 1. ‘House of Bondage’ book cover. A series of photographic essays by Ernest Cole. Random House publishers. Source: amazon.com

Cole then found another job as a floor sweeper and messenger at Zonk Magazine, an Afrikaanse Pers competitor of Jim Bailey’s Drum magazine. While working tat Zonk, he saved up enough money to put down a deposit on two Nikon rangefinder cameras and a few lenses.

In 1958, Cole went to Jurgen Schadeberg - Drum magazine’s chief photographer - and asked him for a job. Schadeberg took him on as his assistant in design and production. During this time, Cole registered for a correspondence course with the New York Institute of Photography. With help and encouragement from the staff at the Institute, his idea of recording apartheid in South Africa was nurtured.

After Drum, he moved on to the Bantu World newspaper (later called The World and now known as The Sowetan) where he was given a job as photographer. In the early 1960s, he started to freelance for clients such as Drum, the Rand Daily Mail, The World and the Sunday Express. Cole was therefore South Africa’s first black freelance photographer.

Cole managed to outwit the Race Classification Board when he was re-classified as a Coloured by changing his name from Kole to Cole. This gave him more privileges and he was soon able to leave South Africa. On 9 May 1966, he left for France, England and New York to showcase his apartheid project and photographs.On the 10 of September 1966, he arrived in New York. He visited the reputable agency Magnum Photos and showed them his photographs. They were so impressed with the images that they organised a publishing deal with The Ridge Press Inc., which in turn sold the publishing rights to Random House. His book, “House of Bondage”, was published in 1967 and was banned in South Africa, although a few copies did manage to get smuggled into the country (figure 1).

This series of photographic essays, set in the 1950s and 1960s, is an indictment of the inhumane conditions under which black South Africans were forced to live during apartheid (figures 2 and 3). The collection is seen as Cole’s single greatest achievement, as he was the first photojournalist to expose to the world the stark realities of life under the apartheid regime. In 1968, Cole was banned from South Africa and settled in the United States.

In the book, Cole writes: "Three-hundred years of white supremacy in South Africa has placed us in bondage, stripped us of our dignity, robbed us of our self-esteem and surrounded us with hate."

Figure 2: Part of House of Bondage series. With no room inside train some ride between cars, Joburg. 1967. Source: artthrob

Figure 2: Part of House of Bondage series. With no room inside train some ride between cars, Joburg. 1967. Source: artthrob

Later, Cole received a grant from the Ford Foundation for a book entitled, ‘A study of the Negro family in the rural South and the Negro family in the urban ghetto’. However, it was never published. Many of the photographs for the publication were taken, but why the book was never published is unknown. The whereabouts of Cole’s photographic negatives, both for “House of Bondage” and the project funded by the Ford Foundation, are currently unknown and original prints are rare.

After some time Cole moved to Sweden where he took up filmmaking. Although he stopped taking photographs, those he had taken were still being used extensively by the African National Congress (ANC) in their newsletters and magazines such as Sechaba. Some were used in books issued by the International Defence and Aid Fund, as well as the UN Special Committee against Apartheid.

In January 1990, Ernest Cole was hospitalised with terminal cancer. On 15 February 1990, his mother left South Africa for the United States to visit him in hospital. He died 2 days later on Saturday 17 December 1990.

A documentary about Cole’s life was filmed by Jurgen Schadeburg in 2006, and includes interviews with his family and rare video footage of his life.

According to Shadeburg, the documentary tells “”¦ the story of a man brave enough to smuggle his camera into the tightly controlled mining compounds, and to click away at pass arrests with his camera hidden in a paper bag. His life was dedicated to showing the world the reality of Apartheid, and to bring image and light to tales of oppression.”

His exhibitions

Cole’s work was featured in several group exhibitions, which include:

- “Photographers on this Display” A photojournalism exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

- “Life Under Apartheid” at the Apartheid Museum, Johannesburg

- “eye Africa” at the Castle's William Fehr Collection, Cape Town from 1960- 1998

- “Colour this Whites Only” at the Tate Museum in London

- “Soweto – A South African Myth - Photographs from the 1950s” which featured work by Cole, Alf Khumalo, Peter Magubane and Jurgen Schadeberg. The focus of the exhibition was the student uprisings of 1976.