Neville Edward Alexander was the first of six children of Dimbiti Bisho Alexander, a primary-school teacher, and David James Alexander, a carpenter. It was in the rural Eastern Cape that he initially kept a strong anti-White sentiment, nurtured by the idea that all Whites were oppressors, an idea which he inherited from his father. Alexander was introduced to coloured militancy and progressivism at an early age. On the other hand, his mother taught him to respect everyone, in addition to introducing him to Christian values.

At an early age, Alexander learned that his grandmother was not originally from South Africa, but it was only later that he discovered how she ended up there. From Ethiopia in East Africa, former slave Bisho Jarsa (Neville’s maternal grandmother) had been freed off the coasts of Yemen to be brought to South Africa as part of an operation aimed at ending the slave trade in the British Empire. Jarsa would later become a teacher at a school in Cradock.

One thing which Neville Alexander remembers being amazed by, was how his grandmother often mumbled to herself in a language (Ethiopia’s Oromo language) none of them understood. His mother told him Jarsa was talking to God, and surely her piety was passed on to Alexander’s mother who, in turn, implanted a sense of biblical values in her son which he still upholds. Neville Alexander was profoundly influenced by his mother’s religious practices and beliefs. Up until he went to university, he attended the Dominican Holy Rosary Convent in Cradock, where he was taught by German nuns. Alexander says: ‘Somehow I did not see the nuns as white. They were almost saintly in the service they rendered us. They were dedicated people, becoming formative role models in my life.’ Alexander learned to enjoy reading and writing, but also to question and investigate, some of the skills that would shape his life later. Precisely, he remembers Sister Veronata, who instilled in him a fondness of German through her methodology. However, one of Alexander’s greatest learning experiences was also to care for the disadvantaged. He came to believe that to be Christian was to work to ensure that the poor would inherit the earth. ‘Today I am an atheist, but I still believe that is what religion is all about. Its great positive contribution to society is to teach people to love and respect one another.’ he said.

University and the becoming of a political activist (1953-1961)

Neville Alexander’s move to Cape Town in 1953 to attend university, marked the beginning of a new phase in his life. Initially, he wanted to become a priest. Alexander was advised to register in medicine at Fort Hare University (UFH) by his school adviser in Cradock, but soon found out he could not apply as he lacked the mathematics background. Therefore, he decided to do a Bachelor of Arts at the University of Cape Town (UCT), majoring in German and History. Soon, his encounter with the secular environment of university changed his approach to religion. Within six months away from home, Alexander felt that he was a religious doubter or an agnostic. Yet, becoming a radical socialist makes sense to him today; even though he could no longer explain the existence of God, he still firmly believed in the ethical values of the Christian faith and his new reasoning never prevented him from working with people when he got back home: ‘I had always been taught to think of other people first. That is why it was so easy for me to become a socialist.’

His contact with the Teachers’ League of South Africa (TLSA), an affiliate of the Non-European Unity Movement (NEUM), heavily influenced the young Alexander. Ronnie Brittan, a TLSA member and a friend of the young boy’s mother, was in charge of looking after Alexander so that he did not get lost in Cape Town, and therefore became the first person Alexander met when arriving in the big city. Brittan had quite an impact on Alexander’s intellectual development, as he introduced him to progressive ideas, atheism, and militant politics. Alexander drew inspiration from this man: ‘To become a teacher, then, became an obvious thing for me, you see. I really admired Ronnie and he was a teacher.’ However, the inspiration Brittan provided him with, was not limited to teaching, for it was in those NEUM meetings that Alexander was forced to become acquainted with the works on ‘pure’ socialism of Karl Marx and Leon Trotsky, and lose his ‘anti-whitism’. After having participated in many educational fellowships debating on national and international politics and helping found the Cape Peninsula Students’ Union, which educated radical political leadership, Alexander enrolled in an Honours and Master (MA) degree at UCT studying German for two years, during which he wrote a thesis on the Silesia Baroque drama of Andreas Gryphius and Daniel Caspar von Lohenstein.

Once he completed his MA, Alexander won an Alexander Humboldt Stiftung scholarship to study at TÁ¼bingen University in (West) Germany, a time which would be crucial not only in the development of his political ideas, but also political actions. By then, he considered himself a Marxist and joined the German Socialist Students’ Union (GSSU). Since his Unity Movement had asked him to remain open to new ideas while there, he met many Algerian and Cuban students who introduced him to anti-colonialism and guerrilla warfare. While in Paris, he even met Trotsky’s wife shortly before she passed away, an encounter which made him more critical of the South African Communist Party and, generally, Stalinist ideas. By 1961, he completed a Ph.D. in German literature. More importantly, by the end of his studies, he made up his mind that he was not going to get married because he realised he would not be able to take care of a family since it was likely he was ‘going to end up in prison’.

Return to Cape Town and ‘an accident waiting to happen’ (1961-1964)

After the Sharpeville massacre, which Neville Alexander witnessed from Germany, he learned that although ‘frustration can be self-defeating’, it can also be ‘at the root of constructive counter-action’. Subsequently, he began seriously considering the possibility of transposing guerrilla warfare and creating revolutionary movements once back in South Africa; however he was suspended from the NEUM when he proposed these ideas. Consequently, he started to have a more leading role in political activism as, although he never saw himself as a political leader, he has always thought that politics are a ‘means to the realisation of a vision’, where his vision is ‘freedom’. Along with Namibian activists Kenneth and Tilly Abraham from the South West Africa People’s Organisation (Swapo), he created the Yu Chi Chan Club (YCCC) to promote guerrilla warfare, and subsequently founded the National Liberation Front (NLF) to bring together people who were committed to the ‘overthrow of the state, irrespective of their political ideology’. However, people in the NEUM and elsewhere considered these activists ‘silly young intellectuals’, for they were””and Alexander agrees with this statement””truly inexperienced and, to use his own words, ‘an accident waiting to happen’.

Meanwhile, Alexander had been teaching at Livingstone High School since 1961 and had made the school more ‘avant-garde’. By stimulating discussions on the discourse and narratives of ‘orthodox history’, by giving students the ‘freedom to explore things for themselves’, Dr. Alexander was now trying to change things from within the educational system. He believed at that point that, as much as it could be admired for its professionalism, the TLSA adopted too much of a ‘British Anglocentric view of what good education should be like’, which was demoralising and stigmatising for people who did not conform to it. In fact, through his work in the NLF, Alexander got involved in underground work and even organised some of his students, but soon he would become a victim of the apartheid judicial system.

Imprisonment on Robben Island (1964-74)

By the end of 1963, the revolutionary movements Neville Alexander was leading, were infiltrated and he and other members of the YCCC were detained, charged and convicted of conspiracy to commit sabotage. Because Dr. Alexander already had certain notoriety, his sentence provoked a number of reactions worldwide. For instance, the Alexander Defense Committee (ADC) was established by I. B. Tabata in New York City, with the aim to provide funds for the legal defence and family support of political prisoners in South Africa, and several branches were opened in Canada and across Europe.

When asked about his experience in the prison of Robben Island, Neville Alexander remembers that it was ‘brutalising’, that both the physical and mental conditions he was put through were terrible. He remembers the humiliation by the prison guards, which took multiple forms: censorship of the prisoners’ denunciations of the tortures they were living; total disinformation of what happened in the world around them; fake humanity on the part of the prison authorities during journalists’ visits and so forth. In addition to this, the crucial lack of education of most of the guards and the ‘opportunism’ of certain prisoners were so many things that he now tries to forget.

This being said, if his experience on Robben Island could be distressing at times, he now believes it was also an ‘ennobling and enriching experience’, where most prisoners became ‘much better people’. According to Alexander, this period (prison term) was an example of true democracy, as he learned to disagree with people while still respecting them. Indeed, the realisation that they all needed each other in a way formed the basis of a new nation. He recalls for instance how, although Nelson Mandela was almost always the spokesperson for the prisoners to negotiate or talk with the authorities, there always was a very democratic process to come to that decision beforehand. There was also a stronger sense of civic responsibility that grew between prisoners. As intense relations and differences emerged in prison, it was necessary for them all ‘to learn to say, “I am sorry” or to say, “I was wrong” without feeling humiliated’.

Moreover, the small scale of living in a prison provided grounds to establish a different but participatory and extremely diverse education. In that respect, the receiving of an Honours degree in History by Alexander only reflected some of the opportunities that came to be offered to””and created by””prisoners. The prison education began with informal seminars, discussions and workshops during working hours, and then, from 1966 onwards, the prisoners were ‘sort of allowed to study’. From this period it became more formal and they could register with the University of South Africa (UNISA) as well as with other correspondence colleges. On the process of educating themselves, Alexander says:

‘We taught one another what we knew, discovering each other’s resourcefulness. We also learned how people with little or no formal education could not only themselves participate in education programmes but actually teach others a range of different insights and skills. The “University of Robben Island” was one of the best universities in the country”¦ it also showed me that you don’t need professors.’

Eventually, they created ‘The Society for the Rewriting of South African History’, and each one of them had his own expertise which he shared with the others: the former Minister of Transport, Mac Maharaj taught economics, Mandela taught law, and Alexander taught history. Progressively, they even ended up educating some warders, some of whom acknowledged they learned a lot from prisoners, with the aim of, perhaps, rehabilitating them as well.

In fact, Mandela and African National Congress (ANC) member Walter Sisulu were fascinated with Alexander’s part-Ethiopian origins, although they did not know about the story of his grandmother as a slave yet. As part of the education offered on Robben Island, Alexander and Mandela particularly encouraged their fellow prisoners to learn their own languages’ reading and writing, as many of them were illiterate at the beginning. By the end of Alexander’s ten-year conviction, illiteracy was not only wiped out in the prison, but he also restarted to speak Xhosa, which he had learned as a child but had lost in later years.

House arrest, Black Consciousness, and Sached (1974-1989)

In 1974, Alexander was released from prison, banned and placed under house arrest for five years. His experience in prison definitely had an influence on his life and his political ideas, and so from the time of his liberation on, Alexander became much more involved in his fight for socialism and active in his writing about it. His comrades and he also began looking for a new ‘political home’, which he, for a short while, tried to find in the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM).

In 1977, Steve Biko who was also banished to King William’s Town in 1973, had tried to meet Alexander in Cape Town, but under the circumstances of having been a Robben Island prisoner and being now banned, Alexander had to be quite cautious. Alexander had already requested Biko to deal with the divisions within his movement as well as some organisational issues. Xolela Mangcu gives his account on the meeting between Alexander and Biko:

‘At that meeting (between Biko and Fikile Bam), Biko had expressed a desire to meet with Bam's close comrade in the Unity Movement, Neville Alexander. And so when Biko and Peter Jones travelled to Cape Town in August 1977 as part of the unity talks among the liberation movements, they relied on Bam to facilitate the meeting with Alexander. However, what enraged Bam - back in 1977 and in our interview - was Alexander's refusal to see Biko on security grounds. While Alexander regards that evening as ‘one of the most tragic moments in my life’, the security concerns were real.’

While grappling with the implications of anti-Vietnam politics and black power on the international scene, domestically Steve Biko’s Black Consciousness Movement was confronting the ravages of apartheid and the Soweto student revolts while trying to co-ordinate underground activity in the country.

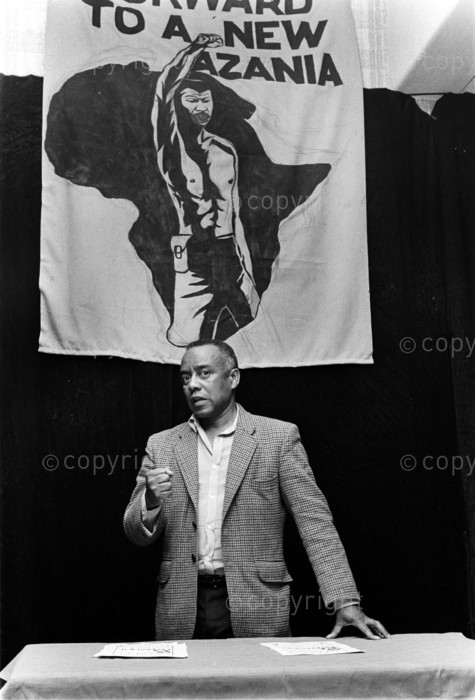

By the end of his house arrest in 1979, Alexander had finished one of his most famous books called One Azania, One Nation: The National Question in South Africa, published under the false name of No Sizwe as it was banned in South Africa. In this book, Alexander attempts to ‘facilitate the unification of the national liberation movement by inciting a discussion to take place on the basis of national unity in South Africa‘, as he felt no refutation of the National Party’s conception of nationality had yet been proposed at the time.

Once his ban ended, Alexander also restarted teaching part-time at UCT in the department of Sociology at the University of Cape Town. Between 1979 and 1986, he was involved in the South African Committee on Higher Education (Sached), an important centre for alternative and anti-apartheid education in which he was later appointed Cape Town director in 1980. The key idea behind this group was ‘Education for Liberation’, as it questioned not only the existing hegemonies, but also looked at the alternative social forms that could be promoted. In the early eighties, he also became associated with the National Forum, which was formed to co-ordinate opposition to the introduction of the tri-cameral Constitution, which was put to a referendum in which only Whites could vote. In 1986, Alexander also became the secretary of the Health, Education and Welfare Society of South Africa, a trust whose goal was to offer funding to a whole range of community projects, always with the intention to empower the oppressed. In the same year, he also helped co-ordinate the National Languages Project in South Africa. In 1989, he attracted a bit more attention when he co-led along with the University of Cape Town’s Institute for the Study of Public Policy a controversial study which concluded that South Africa would remain a multi-lingual society in spite of the emergence of English as a national means of communication in a post-apartheid society.

The 1990s (Wosa, PRAESA, LANGTAG)

In 1990, Alexander wrote a book entitled Education and the Struggle for National Liberation in South Africa, in which he reiterated that efforts put into education would lead to the liberation of South Africa, not the other way round. He said:

‘No government on earth can control the process of schooling completely. The beginnings of trouble in any modern society usually make themselves felt in the schools before they become evident in other institutions precisely because it is so difficult in a modern state to control this process completely.’

Much in the same way as he experienced years before as the YCCC leader and while on Robben Island, schools were the product and the property of the people. Alexander thought that it would be desirable for ‘unconventional’ teaching to be made ‘in such a way that students know exactly what is true, what is half-true, what is simply false, what has been omitted, and why,’ that they, in one word, reflect upon what is been taught to them. This thought followed him all through the last decade of the 20th century.

In April 1990, Alexander headed the Workers’ Organisation for Socialist Action (Wosa) which was created to promote working-class interests. It advocated for Black working class leadership, anti-imperialism, and anti-racism, and demanded fair votes in a non-racial, unitary country. His involvement in the cause came from a concern that the compromises of middle-class leadership ended up further marginalising the majority and ensured that some infrastructure still existed for them in the event of a collapse of capitalist institutions. Basically, Alexander said the programme was ‘almost biblical’ because of its primary interest in fulfilling the most basic needs of the most disadvantaged ones. This being said, despite his reference to Christian faith, he now considered himself overtly an atheist, ‘with no need for the God hypotheses’. Alexander remained convinced that the then-present system would not be able to live up to the hopes and needs of the poorest South Africans, and believed that it should, therefore, be changed for a ‘completely new order’, even if by force. In the 1990s, Wosa was one of the most prominent organisations in South Africa to identify itself with Trotskyist ideas of permanent revolution, and its workers insisted that democracy would only be possible if people could conduct their daily transactions in the language they knew best.

In 1992, the Project for the Study of Alternative Education in South Africa (PRAESA) was founded and housed in the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Cape Town, and one year later Alexander was made director of this independent research development unit. In July 1994, PRAESA organised the first national conference on primary school curriculum initiatives with a series of proposals made to the government to reform the educational system (e.g. involving all actors in curriculum changes, highlighting continuity between educare and primary schooling, etc.). The so-called ‘core curriculum’ was to promote unity among all of the South African people, emphasising the participatory properties of all these suggestions.

With the fall of apartheid, the Language Plan Task Group (LANGTAG) was established in 1995 with the purpose of advising the new Minister of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology, Dr. B. S. Ngubane on a national language plan for South Africa. A committee, chaired by Alexander, was put up to prepare a blueprint for language planning, which was submitted to the Minister in 1996.

The twenty-first century (future of African languages, ACALAN, and prizes)

Not only has Alexander written extensively in the past couple of years for academic journals and books on issues pertaining to language and education in South Africa, but he has also written on his primary interest: socialism. In 2002, on the occasion of the translation of the Communist Manifesto in Zulu, he wrote a foreword for the document. In it, he makes the point that this is an empowering event, although a belated one, which further proves that ‘political education of the emerging leadership of the working class in colonial and postcolonial Africa took place in the languages of the colonial masters, i.e., in French and English’.

In An Ordinary Country: Issues in the Transition from Apartheid to Democracy in South Africa, published in 2003, Alexander makes the point that, after all, South Africa perhaps is not the ‘miracle’ that it is often thought to be. Perhaps it is in fact a ‘very ordinary country’, whose history happened the way it did because its socio-historical circumstances and leaders enabled it. Soon after, the African Academy of Languages (ACALAN) was founded to be the official language policy and planning agency of the African Union, with the permanent objective to design a counter-hegemonic strategy. When one knows about Alexander’s previous experience with, and comments about, language policy in South Africa, it makes sense that he says:

‘Laissez-faire policy notoriously reinforces the agendas of dominant groups. To continue to believe in the twenty-first century that language planning is illusory at best and tantamount to evil social engineering at worst is, ultimately, to deny the possibility of social justice.’

In 2004, he co-chaired a newly-created Steering committee for the Implementation of the Language Plan of Action for Africa (ILPAA) in Yaoundé, Cameroon. The goal of this plan was””and still is””to establish a reference frame to assess all future governmental interventions pertaining to language infrastructure.

The same year, Dr. Neville Alexander received the Order of the Disa, a provincial honour Western Cape Premier Ebrahim Rasool granted to him for his long commitment to socio-political issues and education.

In 2008, he won the Linguapax Prize, granted annually in Barcelona, to highlight his contributions to linguistic diversity and multilingual education during the Mother Language Day, and as part of the Intercultural Week organised by the Ramon Llull University.

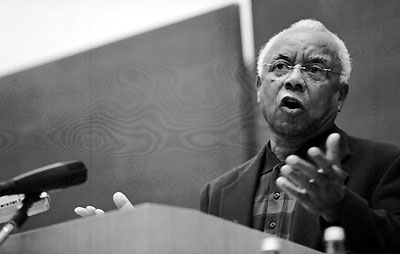

Dr. Neville Alexander was the director of PRAESA and was a member on the Interim Board of the ACALAN.

He passed away on 27 August 2012 in Cape Town, where he resided.

This article was written by Nicolas Magnien and forms part of the SAHO Public History Internship