Diana Mitchell was born in Harare, Zimbabwe, or what was then known as Salisbury, Southern Rhodesia, on 16 November 1932[i]. She was famous for many things, but was most noted for being a liberal politician opposing the White minority regime of Ian Smith's Rhodesia. Her birth name was Diana Mary Coates[ii]. Her father, Elliott Coates, was a naval officer serving in the British merchant marines and her mother, Mary Peck, was originally from Australia[iii]. Mary and Elliott married after Mary fell pregnant with Diana, and the marriage caused a scandal for both the families[iv]. The scandal cost Elliott his job and he was also disinherited by his family. The marriage ended after five years and Mary and Elliot obtained a divorce in 1937[v]. This impacted on Diana as during the early 1940’s she was fostered by another family while her mother worked in a factory[vi].

In 1953, after graduating from Eveline High School in Bulawayo, Diana travelled to Cape Town to attend the University of Cape Town,[vii] where she studied History and Shona, graduating with a BA in History[viii]. When she returned to what was then called Rhodesia she became a teacher, and in 1956 she married an engineer named Brian Mitchell[ix]. In her early years back in Rhodesia she also taught at several different high schools in Gwelo, Fort Victoria and Salisbury.[x]

In 1965, Ian Smith's party, the Rhodesian Front (RF) began to close down various informal schools, known as back yard schools[xi].In 1966, upon seeing a nursery school for the children of Black domestic workers being demolished, she began a campaign to save the school. This campaign later expanded into a national drive to improve education for black children[xii]. During this time she also ran a “backyard school” or an informal school for Black children[xiii]. Diana Mitchell later stated that this was a key moment in her formation as a political activist[xiv]. In later interviews she stated that she could afford to be an activist because her husband took care of them financially[xv]. Her political involvement and activism led her to be one of the founding members of the liberal Centre Party (CP).[xvi]

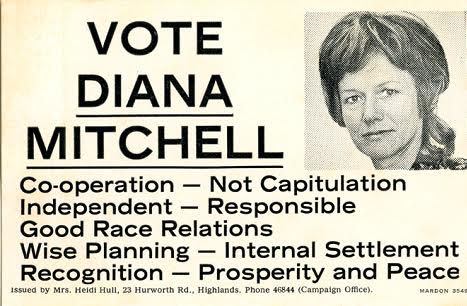

Voting poster for 1974 elections Image source

Voting poster for 1974 elections Image source

Despite being a founding member of the party she was often relegated to speech writing, taking minutes and other administrative tasks[xvii]. She was an outspoken and energetic member, but was relegated to such tasks because of the patriarchal nature of Rhodesian politics[xviii]. In 1975 and 1977 she ran for parliament, but was unsuccessful on both occasions.[xix], but because of the rampant sexism in the party she elected to run as an independent[xx]. In the late 1970’s she was tasked with facilitating peace talks between the RF and the various political movements struggling for national liberation.[xxi]

During the 1970’s Diana continued to work on her educational career and in 1973 she obtained a certificate in Adult Education from what was then called the University of Rhodesia (now the University of Zimbabwe)[xxii]. She also lectured at the University of Rhodesia on the topic of Science Education during 1976[xxiii]. Later she received a MA degree in African History from that same university[xxiv].

With a background in History and Education, and with access to many central political players, Diana Mitchell was perfectly positioned for collecting information on what was happening at the time. Through collecting news reports, minutes from meetings and talking to political leaders she collected an impressive archive of the various African nationalist leaders in Rhodesia[xxv][xxvi]. In 1980, during the negotiations for National Liberation, the book based on the archives, titled “African Nationalist Leaders in Rhodesia: Who's Who”, was used by both sides to inform themselves about Rhodesian oppositional politics at the time[xxvii]. This archive continues to give researchers a great insight into oppositional politics in Rhodesia from the 1960’s – 1980[xxviii]. In 1990, the University of Cape Town acquired, and continues to store, the archive that Diana compiled[xxix]. This archive has been pivotal in showing the active role that women played in the Liberation Struggle, in what is now known as Zimbabwe[xxx].

The role of women in history is often neglected and marginalised, not just in Zimbabwe, but globally. The archives Diana compiled powerfully illustrates that women were at least as politically active as men. By blocking the access of women to taking more public roles and by preventing women from standing for parliamentary elections, the opposition parties in Rhodesia created an idea that the public sphere of opposition politics was a masculine space[xxxi]. This reduced the image of women to being colonial wives and middle class philanthropists[xxxii]. This image was then used to further oppress women's political agency by using their absence in politics as proof for ineptitude.

Diana Mitchell and her brother David in 1979 Image source

Diana Mitchell and her brother David in 1979 Image source

After liberation Diana Mitchell continued to write as a journalist[xxxiii]. She was very critical of the new government of President Robert Mugabe when news of the killings in Matabeleland emerged[xxxiv]. In 1991 she was one of the founding members of the new opposition party, namely the Forum for Democratic Reform, which was a strong proponent of a multi-party democracy[xxxv]. In 2003 Mitchell and her husband emigrated to the United Kingdom, according to some because she was tired of life under the regime of Robert Mugabe[xxxvi]. Diana Mitchell died on the 8 January 2016 [xxxvii]. Diana Mitchell had three children, three grandchildren and four great-grandchildren[xxxviii].

Endnotes

[i] Gallagher, Julia . 2016. “Diana Mitchell obituary” in The Guardian. Accessed 15.03.2015. ↵

[ii] Ibid. ↵

[iii] Law, Kate. 2010. “LIBERAL WOMEN IN RHODESIA: A REPORT ON THE MITCHELL PAPERS, UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN” in History in Africa Vol. 37 (2010), pp. 389-398. Page 390. ↵

[iv] Gallagher, Julia . 2016. “Diana Mitchell obituary” in The Guardian. Accessed 15.03.2015. ↵

[v] Ibid. ↵

[vi] Ibid. ↵

[vii] Law, Kate. 2010. “LIBERAL WOMEN IN RHODESIA: A REPORT ON THE MITCHELL PAPERS, UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN” in History in Africa Vol. 37 (2010), pp. 389-398. Page 390. ↵

[viii] Ibid. ↵

[ix] Colonial Relic. http://www.colonialrelic.com/about/. Accessed 15.03.2015. ↵

[x] Ibid. ↵

[xi] Law, Kate. 2010. “LIBERAL WOMEN IN RHODESIA: A REPORT ON THE MITCHELL PAPERS, UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN” in History in Africa Vol. 37 (2010), pp. 389-398. Page 390. ↵

[xii] Gallagher, Julia . 2016. “Diana Mitchell obituary” in The Guardian. Accessed 15.03.2015. ↵

[xiii] Law, Kate. 2010. “LIBERAL WOMEN IN RHODESIA: A REPORT ON THE MITCHELL PAPERS, UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN” in History in Africa Vol. 37 (2010), pp. 389-398. Page 390. ↵

[xiv] Ibid. ↵

[xv] Ibid. ↵

[xvi] Ibid. ↵

[xvii] Ibid. Delete spaces ↵

[xviii] Ibid. Delete spaces ↵

[xix] Ibid. ↵

[xx ]Gallagher, Julia . 2016. “Diana Mitchell obituary” in The Guardian. Accessed 15.03.2015. ↵

[xxi] Ibid. ↵

[xxii] Colonial Relic. http://www.colonialrelic.com/about/. Accessed 15.03.2015. ↵

[xxiii] Ibid. ↵

[xxiv] Ibid. ↵

[xxv] Gallagher, Julia . 2016. “Diana Mitchell obituary” in The Guardian. URl number Accessed 15.03.2015. ↵

[xxvi] Mitchell, Diana M., and Robert Cary. 1977. “African Nationalist Leaders in Rhodesia: Who's Who” (Salisbury, Name of Publisher?1977). ↵

[xxvii] Gallagher, Julia . 2016. “Diana Mitchell obituary” in The Guardian. Accessed 15.03.2015. ↵

[xxviii] Law, Kate. 2010. “LIBERAL WOMEN IN RHODESIA: A REPORT ON THE MITCHELL PAPERS, UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN” in History in Africa Vol. 37 (2010), pp. 389-398. Page 390. ↵

[xxix] Ibid. ↵

[xxx] Ibid. Page 391. ↵

[xxxi] Ibid. Page 392. ↵

[xxxii] Ibid. ↵

[xxxiii] Gallagher, Julia . 2016. “Diana Mitchell obituary” in The Guardian. Accessed 15.03.2015. ↵

[xxxiv] Ibid. ↵

[xxxv] Mitchell Diana. 2004. “Colonial Relic”. http://colonialrelic.blogspot.co.za/2007_03_01_archive.html. Accessed 12.04.2015 ↵

[xxxvi] Ibid. ↵

[xxxvii] Ibid. ↵

[xxxviii] Ibid. ↵