Ashley Kriel was born on the 17 October 1966 to Ivy and Melvin Kriel. He has two sisters, Michel Assure and Melaney Adams. He grew up in Bonteheuwel, Cape Town. Bonteheuwel is a township on the Cape Flats and was predominantly working class. In the context of the Group Areas Act, it was a ‘coloured’ designated area. This meant that many of the families that lived in this area had been forcibly removed from District Six or other areas around Cape Town that had been designated ‘white’ areas under the Act.

Kriel went to school in Bonteheuwel, starting at Central Park Primary School. He started high school in 1981 at Bonteheuwel High. Despite a year at Athlone High School in 1982, he would return to Bonteheuwel High and finish his education there in 1985. Kriel was a strong student, excelling in science and mathematics specifically.[1] This is evidenced by his attendance of the Cape Argus Winter School for Science in 1984. At this time, Kriel was described as being a “voracious reader [...] and an engaging conversationalist.”[2] Kriel was also religious, evidenced by his attendance of the Moravian Church Youth camp in 1984. This did not detract from his political involvement, however.

Kriel was a member of various student groups while in school, where he developed his public speaking and organisational skills. He was a member of the Bonteheuwel Inter-schools Congress (BISCO) “[...] which was formed to coordinate the activities of the student representative councils (SRCs) of Arcadia High, Bonteheuwel High and Modderdam High Schools ,and Bonteheuwel Youth Movement, BYM, (an affiliate of the Cape Youth Congress, CAYCO).”[3] Kriel was described by his family and friends as a natural born leader and very politically aware. As a result of these leadership skills, Kriel soon became an influential leader of the youth in Bonteheuwel, despite still being a teenager. Along with close friends Henriette Abrahams, Kriel organised the youth of Bonteheuwel into school boycotts, protests and other actions in line with the ANC’s call to make the country ‘ungovernable’ with plans that the inter-school SRC named ‘Days of Action’.

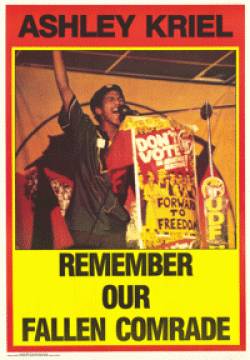

Poster commemorating Ashley Kriel Image source

Poster commemorating Ashley Kriel Image source

As a result of the unrest in Bonteheuwel, the apartheid Security Police assigned a special unit to the area. Kriel was one of ‘The Five’ student leaders who were specifically targeted by this unit. They included Anton Fransch, Andrew ‘Gorrie’ November, Coline Williams, and Gary Holtzman. Of the five, three would be dead by 1990 with Coline Williams and Anton Fransch being killed in 1989. Due to the intense attention by the Security Police, Kriel had to go underground. He was only 18 years old. While he was underground, he became part of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the armed wing of the ANC. Eventually, Kriel had to go into exile on 27 December 1985. He was helped by various members of the ANC and MK, and was moved across various borders. He finally ended up at an MK training camp, named Kibashe, in Angola. While at this camp, various acquaintances and friends state that Kriel grew into manhood. Gary Holtzman remarks in Action Kommandant that he was surprised to find that Kriel was now ‘proficient in Zulu’. He was trained in the use of various small firearms as well as in the use of homemade explosives and unarmed combat. As in his school days, Kriel was a leader. This leadership caused headaches for the likes of Joe Slovo and Chris Hani as they were unsure whether to retain him in exile as a top member of the instructorate. or send him back to South Africa. The decision seemed to have been made to send him back to South Africa, as in 1987, Ashley Kriel re-entered the country via Lusaka and then Gaborone.

Due to the nature of actions in which MK operatives were involved, they had to operate in secrecy. As such, Kriel was not able to contact his family or friends. He did, however, take up residence in the back-room of his old teachers house. From here, Kriel co-ordinated with Nicklo Pedro, another MK operative. Yet, his isolation did not prove to be wholly protective. On 9 July 1987, Kriel answered the door to his room, thinking that the men outside were municipal workers. The events that followed are disputed. The official police record states that Kriel was carrying a pistol under a towel. When he opened the door, the policemen disguised as municipal workers pushed in, and in the ensuing scuffle to get Kriel in handcuffs, his pistol fired. Kriel died of his wounds shortly afterwards. This version of the events was outlined by Captain Jeffrey Benzien, a member of the Bonteheuwel unit of the Security Police, at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) hearings. An independent forensic investigator, Dr David Klatzow, refutes this version of events. He states, in Action Kommandant, that the forensic evidence does not support Benzien’s testimony. Specifically, Klatzow points to the fact that the gunshot wounds on Kriel’s body were not close contact wounds but rather consistent with a shot fired from further away. Benzien was granted amnesty by the TRC for the killing of Kriel, amongst other apartheid era crimes.

As Kriel’s family did not know he was in the country, his death came as a huge shock to them. His funeral was held on 20 July 1987 and became a site of contestation between the police and the people of Bonteheuwel. Kriel’s stature in the community was evidenced by the attendance of the likes of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Dr Allan Boesak and Molena Faried Essack. Chaos ensued after the funeral when the police tried to remove an ANC flag that was draped over Kriel’s coffin. Essack and Boesak threw themselves on the flag to stop the police from removing it. Kriel’s coffin was then borne by the crowds amid the flying teargas canisters.

Ashley Kriel was posthumously awarded the Joe Modise Commanding and Leadership Excellence award, as well as the Stamza Bopape Young Martyr Memorial Award on the 27 October 1996.

End notes:

[1]www.ashleykrielyouth.org/?page_id=13 ↵

[2]www.ashleykrielyouth.org/?page_id=13 ↵

[3]www.ashleykrielyouth.org/?page_id=13 ↵