Desmond Mpilo Tutu (known fondly as the "Arch”) was born in Klerksdorp on 7 October 1931. His father, Zachariah, who was educated at a Mission school, was the headmaster of a high school in Klerksdorp, a small town in the Western Transvaal (now North West Province). His mother, Aletha Matlhare, was a domestic worker. They had four children, three girls and a boy. This was a period in South African history that predated formal apartheid but was nonetheless defined by racial segregation.

Tutu was eight years old when his father was transferred to a school that catered for African, Indian and Coloured children in Ventersdorp. He also was a pupil at this school, growing up in an environment where there were children from other communities. He was baptised as a Methodist but it was in Ventersdorp that the family followed his sister, Sylvia’s lead into the African Methodical Episcopal Church and finally in 1943 the entire family became Anglicans.

Zachariah Tutu was then transferred to Roodepoort, in the former Western Transvaal. Here the family were forced to live in a shack while his mother worked at the Ezenzeleni School of the Blind. In 1943, the family was forced to move once more, this time to Munsieville, a Black settlement in Krugersdorp. The young Tutu used to go to White homes to offer a laundry service whereby he would collect and deliver the clothes and his mother would wash them. To earn extra pocket money, together with a friend, he would walk three miles to the market to buy oranges, which he would then sell for a small profit. Later he also sold peanuts at railway stations and caddied at a golf course in Killarney. Around this age, Tutu also joined the Scouting movement and earned his Tenderfoot, Second Class and Proficiency Badge in cooking.

In 1945, he began his secondary education at the Western High, a Government secondary school in the old Western Native Township, near Sophiatown. At about this time he was hospitalised for over a year, with tuberculosis. It was here that he was befriended by Father Trevor Huddleston. Father Huddleston brought him books to read and a deep friendship developed between the two. Later, Tutu became a server at Father Huddleston’s parish church in Munsieville, even training other boys to become servers. Apart from Father Huddleston, Tutu was influenced by the likes of Pastor Makhene and Father Sekgaphane (who admitted him into the Anglican Church), and the Reverend Arthur Blaxall and his wife in Ventersdorp.

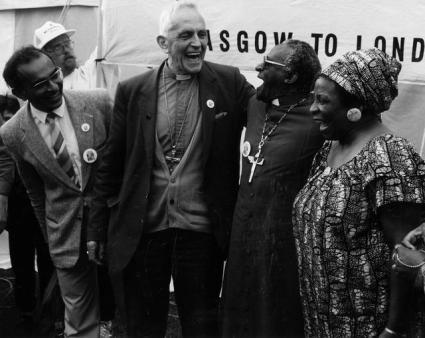

Abdul Minty, Father Trevor Huddleston, Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Adelaide Tambo at the Nelson Mandela Freedom March, England, July 1988. Image source

Abdul Minty, Father Trevor Huddleston, Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Adelaide Tambo at the Nelson Mandela Freedom March, England, July 1988. Image source

Although he had fallen behind at school, owing to his illness, his principal took pity on him and allowed him to join the Matriculation class. At the end of 1950, he passed the Joint Matriculation Board examination, studying into the night by candlelight. Tutu was accepted to study at the Witwatersrand Medical School but was unable to obtain a bursary. He thus decided to follow his father’s example and become a teacher. In 1951, he enrolled at the Bantu Normal College, outside Pretoria, to study for a teacher’s diploma.

In 1954, Tutu completed a teaching diploma from the Bantu Normal College and taught at his old school, Madipane High in Krugersdorp. In 1955, he also obtained a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Africa (UNISA). One of the people that helped him with his University studies was Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe, the first president of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC).

The Arch and wife Leah have a laugh before their wedding ceremony begins. Picture: ANA Image source

The Arch and wife Leah have a laugh before their wedding ceremony begins. Picture: ANA Image source

On 2 July 1955, Tutu married Nomalizo Leah Shenxane, one of his father’s brightest pupils. After their marriage, Tutu began teaching at Munsieville High School, where his father was still the headmaster, and where he is remembered as an inspiring teacher. On 31 March 1953 Black teachers and pupils alike were struck a massive blow when the government introduced the Bantu Education Act Black education, which restricted Black education to a rudimentary level. Tutu continued in the teaching profession for three more years following this, seeing through the education of those children that he had begun teaching at junior level. After that he quit in protest against the political undermining of Black education.

During his tenure at Munsieville High, Tutu thought seriously about joining the priesthood, and eventually offered himself to the Bishop of Johannesburg to become a priest. By 1955, together with his former scoutmaster, Zakes Mohutsiou, he was admitted as a sub-Deacon at Krugersdorp, and in 1958, he enrolled at St Peter's Theological College in Rosettenville, which was run by the Fathers of the Community of the Resurrection. Here Tutu proved to be a star student, excelling at his studies. He was awarded licentiate of Theology with two distinctions. Tutu still regards the Community of Resurrection with reverence and considers his debt to them as incalculable.

He was ordained as a deacon in December 1960 at St Mary’s Cathedral, Johannesburg and took up his first curacy at St Albans Church in Benoni. By now, Tutu and Leah had two children, Trevor Thamsanqa and Thandeka Theresa. A third, Nontombi Naomi, was born in 1960. At the end of 1961, Tutu was ordained as a priest, following which he was transferred to a new church in Thokoza. Their fourth child, Mpho, was born in London in 1963.

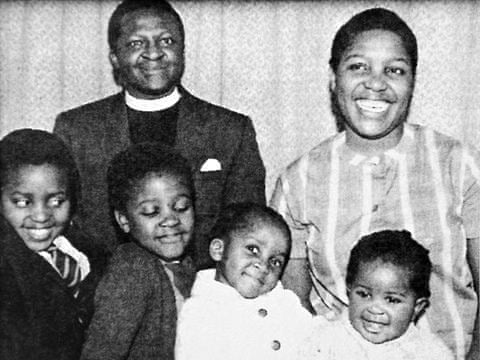

Desmond Tutu and his wife, Leah, and their children, from left: Trevor Thamsanqa, Thandeka Theresa, Nontombi Naomi and Mpho Andrea, England, c1964. (c) Mpilo Foundation Archives, courtesy Tutu family Image source

Desmond Tutu and his wife, Leah, and their children, from left: Trevor Thamsanqa, Thandeka Theresa, Nontombi Naomi and Mpho Andrea, England, c1964. (c) Mpilo Foundation Archives, courtesy Tutu family Image source

On 14 September 1962, Tutu arrived in London to further his theological studies. Money was obtained from various sources and he was given bursaries by Kings College in London and awarded a scholarship by the World Council of Churches (WCC). In London, he was met at the airport by writer Nicholas Mosley, an arrangement co-ordinated by Father Alfred Stubbs, his former lecturer in Johannesburg. Through Mosley, the Tutus met Martin Kenyon who was to be a lifelong friend of the family.

London was an exhilarating experience for the Tutu family after the suffocation of life under apartheid. Tutu was even able to indulge in his passion for cricket. Tutu enrolled at Kings College, at the University of London, where he again excelled. He graduated at the Royal Albert hall where the Queen Mother, who was the Chancellor of the University, awarded him his degree.

His first experience of ministering to a White congregation was in Golders Green, London, where he spent three years. Then he was transferred to Surrey to preach. Father Stubbs encouraged Tutu to enrol for a postgraduate course. He entered an essay on Islam for the ‘Archbishop’s Essay Prize’ and duly won. He then decided that this was to be the subject of his Masters degree. Tutu had such a profound influence over his parishioners that after he had completed his Masters degrees in the Arts in 1966, the entire village where he was the priest turned out to bid him farewell.

Tutu then returned to South Africa and taught at the Federal Theological Seminary at Alice in the Eastern Cape, where he was one of six lecturers. Apart from being a lecturer at the Seminary, he was also appointed as the Anglican Chaplain to the University of Fort Hare. At the time, he was the most highly qualified Anglican clergyman in the country. In 1968, while he was still teaching at the Seminary, he wrote an article on the theology of migrant labour for a magazine called the South African Outlook.

At Alice he began working on his Doctorate, combining his interest in Islam and the Old Testament, although he did not complete it. At the same time, Tutu began making his views against apartheid known. When the students at the Seminary went on protest against racist education, Tutu identified with their cause.

He was earmarked to be the future Principal of the Seminary and was, in 1970, due to become the Vice-Principal. However, with mixed feelings he accepted an invitation to become a lecturer at the University of Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland, based at Roma in Lesotho. During this period, “Black Theology” reached South Africa and Tutu espoused this cause with great enthusiasm.

In August 1971, Dr Walter Carson, the acting Director of the Theological Education Fund (TEF), which was started in 1960 to improve theological education in the developing world,

asked Tutu to be shortlisted for the post of Associate Director for Africa. Thus the Tutu family arrived in England in January 1972, where they set up home in southeast London. His job entailed working with a team of international directors and the TEF team. Tutu spent almost six months travelling to Third World countries and was especially excited at being able to travel in Africa. At the same time, he was licensed as an Honorary Curate at St Augustine’s Church in Bromley where, again, he made a deep impression on his parishioners.

In 1974 Leslie Stradling, the Bishop of Johannesburg, retired and the search for his successor began. However, Timothy Bavin, who had consistently voted for Tutu during the elective process, was elected as Bishop. He then invited Tutu to become his Dean. Tutu thus returned to South Africa in 1975 to take up the post as the first Black Anglican Dean of Johannesburg and the Rector of St Mary’s Cathedral Parish in Johannesburg. Here he brought about radical changes, often to the chagrin of some his White parishioners.

On 6 May 1976, he sent an open letter to the then Prime Minister, John Vorster reminding him of how Afrikaners had obtained their freedom and, inter alia, drew his attention to the fact that Blacks could not attain freedom in the homelands; the horrors of the pass laws; and discrimination based on race. He requested that a National Convention of recognised leaders be called and suggested ways in which the Government could prove its sincerity in its oft quoted refrain of wanting peaceful change. Three weeks later, the Government replied asserting that his motive in writing the letter was to spread political propaganda.

On 16 June 1976, Soweto students began a wide scale rebellion against being forced to accept Afrikaans as the language of instruction as well as the inferior education they were forced to endure. Tutu was the Vicar General when he received news of the police massacre and murdered students. He spent the day engaged with students and parents, and thereafter played a significant role in the Soweto Parents Crisis Committee which was set up in the aftermath of the killings.

Following this, Tutu was persuaded to accept the position of Bishop of Lesotho. After much consultation with his family and church colleagues, he accepted, and on 11 July 1976 he underwent his consecration. During his visit to rural parishes, he often travelled on horseback, sometimes for up to eight hours. Whilst in Lesotho, he did not hesitate to criticise the unelected Government of the day. At the same time, he groomed a Lesotho national, Philip Mokuku to succeed him. It was also while he was still in Lesotho that he was invited to deliver the funeral oration at the freedom fighter, Steve Biko’s funeral. Biko was killed in detention by the South African Police.

After only a few months in his new post, Tutu was invited to become the General Secretary of the South African Council of Churches (SACC), which he took up on 1 March 1978. In 1981, Tutu became the Rector of St Augustine’s Church in Orlando West, Soweto and as early as 1982 he wrote to the Prime Minister of Israel appealing to him to stop bombing Beirut; while at the same time writing to Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, calling on him to exercise ‘a greater realism regarding Israel’s existence’. He also wrote to the Prime Ministers of Zimbabwe, Lesotho and Swaziland and the Presidents of Botswana and Mozambique thanking them for hosting South African refugees and appealing to them not to return any refugee back to South Africa.

All of this brought critical and angry responses from conservative South African Whites and at times even the mainstream media, yet on no occasion did Tutu forget his calling as a priest. Whilst at the SACC, he asked Sheena Duncan, President of the Black Sash to start Advice Offices. He also began the Education Opportunities Council to encourage South Africans to be educated overseas. Of course, he also maintained his stringent criticism of the Government’s policy of forced removals of Blacks and the homelands system.

In 1983, when the people of Mogopa, a small village in the then Western Transvaal, were to be removed from their ancestral lands to the homeland of Bophuthatswana and their homes destroyed, he phoned church leaders and arranged an all night vigil at which Dr Allan Boesak and other priests participated.

At times Tutu was criticised for the time he spent travelling overseas. However, these trips were necessary to raise funds for SACC projects. Whilst he was outspokenly critical of the Government, he was equally magnanimous in praising or showing gratitude when victories for the anti-apartheid movement were forthcoming - for instance, when he congratulated the Minister of Police, Louis le Grange, for allowing political prisoners to do post matriculation studies.

In the 1980s, Tutu earned the wrath of conservative White South Africans when he said that there would be a Black Prime Minister within the next five to ten years. He also called on parents to support a school boycott and warned the Government that there would be a repetition of the 1976 riots if it continued to detain protesters. Tutu also condemned the President’s Council where a proposal for an electoral college of Whites, Coloureds and Indians was going to be established. On the other hand, at a conference at the University of Witwatersrand in 1985, convened by the Soweto Parents Crisis Committee, Tutu warned against an uneducated generation who would not have the requisite skills to occupy positions in a post Apartheid South Africa.

On 7 August 1980, Bishop Tutu and a delegation of church leaders and the SACC met with Prime Minister PW Botha and his Cabinet delegation. It was an historic meeting in that it was the first time a Black leader, outside the system, talked with a White Government leader. However, nothing came of the talks, as the Government maintained its intransigent position.

In 1980, Tutu also took part in a march along with other church leaders in Johannesburg, calling for the release of John Thorne, a church Minister who was detained. The clergy were arrested under the riotous Assemblies Act and Tutu spent his first night in detention. It was a traumatic experience, resulting in death threats, bomb scares, and pernicious rumours being spread about the bishop. During this period, Tutu was constantly vilified by the government. Furthermore, the Government sponsored organisations such as the Christian League, which accepted money to conduct anti SACC campaigns and thus further undermine Tutu’s influence.

Desmond Tutu in jail. Image source

Desmond Tutu in jail. Image source

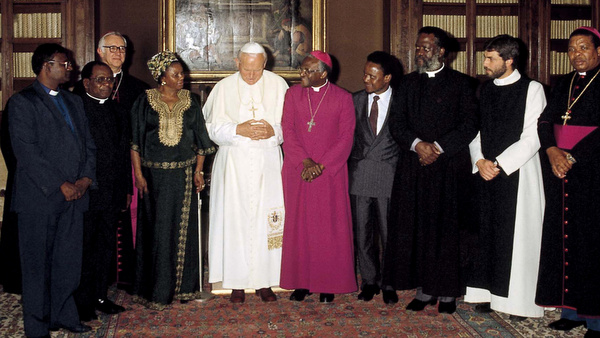

During his overseas trips, Tutu spoke out persuasively against Apartheid; the migrant labour system; and other social and political ills. In March 1980, the Government withdrew Tutu’s passport. This prevented him from travelling overseas to accept awards that were being bestowed upon him. For instance, he was the first person to be awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Ruhr, West Germany, but was unable to travel having being denied a passport. The Government finally returned his passport in January 1981, and he was consequently able to travel extensively to Europe and America on SACC business, and in 1983 Tutu had a private audience with the Pope where he discussed the situation in South Africa.

Pope John Paul II meets with Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu, center right, in 1983 at the Vatican. (CNS photo/Giancarlo Giuliani, Catholic Press Photos) Image source

Pope John Paul II meets with Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu, center right, in 1983 at the Vatican. (CNS photo/Giancarlo Giuliani, Catholic Press Photos) Image source

Download a list of all Desmond Tutu's awards and honours here (pdf)

The Government continued its persecution of Tutu throughout the 1980s. The SACC was obliquely accused by government of receiving millions of rands from overseas to foment unrest. To show that there was no truth in the claim, Tutu challenged the government to charge the SACC in an open court but the Government instead appointed the Eloff Commission of Enquiry to investigate the SACC. Eventually the commission found no evidence of the SACC being manipulated from overseas.

In September 1982, after eighteen months without a passport, Tutu was issued with a limited ‘travel document’. Again, he and his wife travelled to America. At the same time many people lobbied for the return of Tutu's passport, including George Bush, then Vice President of the United States of America. In the United States, Tutu was able to educate Americans about Nelson Mandela and Oliver Tambo, of whom most Americans were ignorant. At the same time, he was able to raise funds for numerous projects in which he was involved. During his visit, he also addressed the United Nations Security Council on the situation in South Africa.

Tutu was heavily involved in the UDF, and elected to be its patron in 1983 Image source

Tutu was heavily involved in the UDF, and elected to be its patron in 1983 Image source

In 1983, he attended the launch of the National Forum, an umbrella body of Black Consciousness groups and the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). In August 1983, he was elected Patron of the United Democratic Front (UDF). Tutu’s anti-apartheid and community activism was complemented by that of his wife, Leah. She championed the cause for better working conditions for domestic workers in South Africa. In 1983, she helped found the South African Domestic Workers Association.

Leah Tutu Image source

Leah Tutu Image source

On 18 October 1984, whilst in America, Tutu learnt that he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize award for his effort in calling for an end to White minority rule in South Africa; the unbanning of liberation organisations; and the release of all political prisoners. The actual award took place at the University of Oslo, Norway on 10 December 1984. While Black South Africans celebrated this prestigious award, the Government was silent, not even congratulating Tutu on his achievement. There was mixed reaction from the public with some showering him with praise and others preferring to denigrate him. On November 1984, Tutu learnt that was elected as the Bishop of Johannesburg. At the same time his detractors, mainly Whites (and a few Blacks e.g. Lennox Sebe, leader of the Ciskei) were not happy with his election. He spent eighteen months in this post before being finally elected to the position of Bishop of Cape Town in 1985. He was the first Black man to occupy the post.

In another visit to America in 1984, Tutu and Dr Allan Boesak met with Senator Edward Kennedy and invited him to visit South Africa. Kennedy accepted the offer and in 1985 he arrived, visiting Winnie Mandela in Brandfort, Orange Free State where she was banished and spending the night with the Tutu family in defiance of the Group Areas Act. However, the visit was mired in controversy and the Azanian Peoples Organisation (AZAPO) mounted demonstrations against the Kennedy visit.

South African Bishop Desmond Tutu, right, welcomes US Senator Edward Kennedy on his arrival in Johannesburg, January 5, 1985 Picture: REUTERS Image source

South African Bishop Desmond Tutu, right, welcomes US Senator Edward Kennedy on his arrival in Johannesburg, January 5, 1985 Picture: REUTERS Image source

In Duduza on the East Rand in 1985, Tutu, with the assistance of Bishops Simeon Nkoane and Kenneth Oram intervened to save the life of a Black police officer, accused of being a police spy by a crowd who wanted to execute him. A few days later, at a huge funeral in KwaThema, East Rand, Tutu denounced violence and brutality in all forms; whether it was precipitated by the Government or by people of colour.

In 1985, the Government imposed a State of Emergency in 36 magisterial districts. Severe restrictions were placed on ‘political’ funerals. Tutu called on the Minister of Police to reconsider these regulations and stated that he would defy them. Tutu then sent a telegram to Prime Minister Botha requesting an urgent meeting to discuss the situation. He received a telephone call informing him that Botha had refused to see him. Nearly a year later he met with Botha, but nothing came of this meeting.

Tutu also had a fruitless meeting with British Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, who was a supporter of the South African Government and later refused to meet with British Foreign Secretary, Geoffrey Howe, on his visit to South Africa. His 1986 fundraising tour to America was widely reported on by the South African press, often out of context, especially his call on Western Governments to support the banned African National Congress (ANC), which at the time, was a risky thing to do.

In February 1986 Alexandra Township Johannesburg went up in flames. Tutu together with Reverend Beyers Naude, Dr Boesak and other church leaders went to Alexandra Township and helped to defuse the situation there. He then travelled to Cape Town to see Botha, but again he was snubbed. Instead, he met Adriaan Vlok, the Deputy Minister of Law, Order and Defence. He reported to the residents of Alexandra that none of their demands were met and that the Government only said it was going to look into their requests. However, the crowd was not convinced and some became angry while some young people booed him forcing him to leave.

On 7 September 1986, Tutu was ordained as the Archbishop of Cape Town, becoming the first Black person to lead the Anglican Church of the Province of Southern Africa. Again, there was great jubilation at him being chosen as the Archbishop, but detractors were critical. At the Goodwood Stadium over 10,000 people gathered in his honour for the Eucharist. The exiled ANC President Oliver Tambo and 45 Heads of State sent their congratulations to him.

A year after the first democratic elections that saw the end of White minority rule in 1994, Tutu was appointed Chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), to deal with the atrocities of the past. Tutu retired as the Archbishop of Cape Town in 1996 in order to devote all his time to the work of the TRC. He was later named as the Archbishop Emeritus. In 1997, Tutu was diagnosed with prostate cancer and underwent successful treatment in America. Despite this ailment, he continued to work with the commission. He subsequently became patron of the South African Prostate Cancer Foundation, which was established in 2007.

In 1998 the Desmond Tutu Peace Centre (DTPC) was co-founded by Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Mrs. Leah Tutu. The Centre plays a unique role in building and leveraging the legacy of Archbishop Tutu to enable peace in the world.

In 2004 Tutu returned to the United Kingdom to serve as a visiting professor at King’s College. He also spent two years, as Visiting Professor of Theology at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, and continued to travel extensively to pursue justice for worthy causes, inside and out of his country. Within South Africa, one of his main focuses has been on health, particularly the issue of HIV/AIDS and Tuberculosis. In January 2004 the Desmond Tutu HIV Foundation was formally established under the directorship of Professor Robin Wood and Associate Professor Linda-Gail Bekker. The Foundation had its beginnings as the HIV Research Unit based at New Somerset Hospital in the early 1990s and is known as one of the first public clinics to offer anti-retroviral therapy to those living with HIV.

More recently, the foundation, supported by Emeritus Archbishop Desmond and Leah Tutu, extended its activities to include HIV treatment, prevention and training as well as tuberculosis treatment monitoring in the hardest hit communities of the Western Cape.

Tutu continues to speak out on moral and political issues affecting South Africa and other countries. Despite his long standing support for the ANC, he has not been afraid to criticise the Government and the ruling party when he felt that it had fallen short of the democratic ideals that many people fought for. He has repeatedly appealed for peace in Zimbabwe and compared the actions of former Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe's government to those of the South African apartheid regime. He is also a supporter of the Palestinian cause and the people of East Timor. He is an outspoken critic of the mistreatment of prisoners at Guantanamo Bay and has spoken out against human rights abuses in Burma. While she was still under house arrest as a prisoner of the state, Tutu called for the release of Aung San Suu Kyi, the former leader of Burma’s opposition and fellow Nobel Peace Prize winner. However, once Suu Kyi was released, Tutu was likewise unafraid to publicly criticise her silence in the face of violence against the Rohingya people in Myanmar.

In 2007, Tutu joined former President Nelson Mandela; former U.S. President Jimmy Carter; retired U.N Secretary General Kofi Annan; and former Irish President Mary Robinson to form The Elders, a private initiative mobilizing the experience of senior world leaders outside of the conventional diplomatic process. Tutu was selected to chair the group. Subsequent to this, Carter and Tutu travelled together to Darfur, Gaza and Cyprus in an effort to resolve long-standing conflicts. Tutu’s historic accomplishments and his continuing efforts to promote peace in the world were formally recognized by the United States in 2009, when President Barack Obama named him to receive the nation's highest civilian honour, the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Tutu officially retired from public life on 7 October 2010. However, he continues with his involvement with the Elders and Nobel Laureate Group and his support of the Desmond Tutu Peace Centre. He did, however, step down from his positions as Chancellor of the University of the Western Cape and as a representative on the UN's advisory committee on the prevention of genocide.

In the week leading to his 80th birthday, Tutu was cast into the spotlight. Tibet’s spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, who went into exile in 1959 after leading an uprising against Chinese rule, was invited by Tutu to deliver the inaugural Desmond Tutu International Peace lecture during the three-day celebration of Tutu's 80th birthday in Cape Town. The South African Government procrastinated while deciding whether to issue the Dalai Lama with a visa, probably cognisant that by so doing they risked upsetting their allies in China. By 4 October 2011, the Dalai Lama has still not been granted a visa and he therefore cancelled his trip, saying that he was not going to come to South Africa after all, as the South African government found it ‘inconvenient’ and he did not want to place any individual or the Government in an untenable position. The Government caught on its back foot tried to defend its tardiness. South Africans from across the socio-political spectrum, religious leaders, academics and civil society, united in condemning the Government’s actions. In a rare show of fury Tutu launched a blistering attack on the ANC and President Jacob Zuma, venting his anger at the Government’s position regarding the Dalai Lama. The Dalai Lama had been previously refused a visa to visit South Africa in 2009.Tutu and the Dalai Lama did go on to write a book together nonetheless.

In more recent years, Tutu has been prone to health problems related to his prostate cancer. However, notwithstanding his frail health, Tutu continues to be highly revered for his knowledge, views and experience, especially in reconciliation. In July 2014 Tutu stated that he believed a person should have the right to die with dignity, a view he discussed on his 85th birthday in 2016. He continues to criticise the South African government over corruption scandals and what he says is the loss of their moral compass.

His daughter, Mpho Tutu-van Furth, married her female partner Professor Marceline van Furth in May 2016, which led him to be even more vocal than before in support of homosexual rights internationally and within the Anglican Church. Tutu has never stopped publicly speaking out against what he considers immoral behaviour, whether in China Europe, or the United States. It was Tutu who coined the popular phrase, the 'Rainbow Nation' to describe the beauty in difference to be found among all the different people in South Africa. Even though the term's popularity has waned over the years, the ideal of a united harmonious South African nation is still one that is yearned for.

In 2015, to celebrate their 60th wedding anniversary, Tutu and Leah renewed their vows

Tutu passed away on the 26th of December 2021

Archbishop Desmond Tutu (L) and his wife Nomalizo Leah share a smile during the ceremony Photo: AFP Image source

Archbishop Desmond Tutu (L) and his wife Nomalizo Leah share a smile during the ceremony Photo: AFP Image source