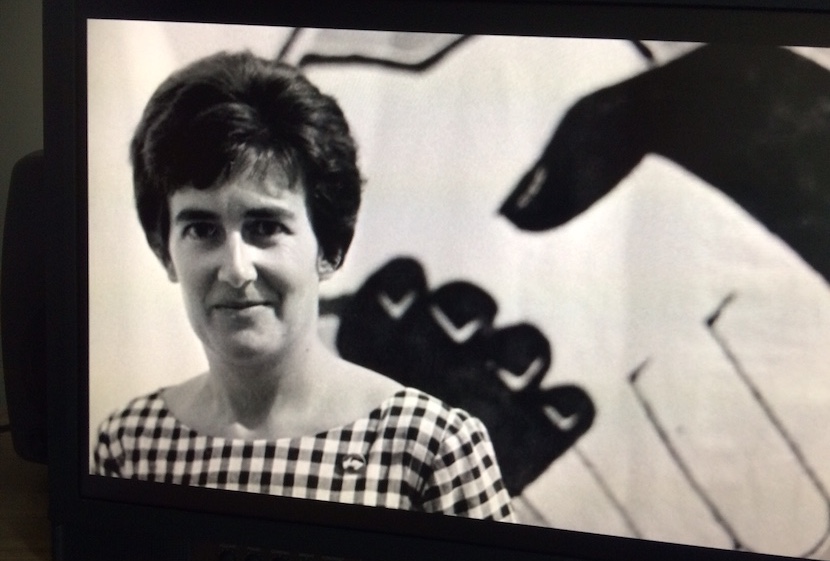

Anti-apartheid activist Adelaine Hain who was successively jailed, banned and exiled to Britain in Pretoria in the early 1960s died peacefully on 8 September, aged 92, surrounded by her family in Neath, South Wales. Hain's banishment to Britain failed to quell her anti-apartheid voice. Instead in 1969-70 she continued to play a leading role with her son, Peter in stopping white South African sports tours with militant protests.

Adelaine Hain was born Adelaine Florence Stocks in Port Alfred, South Africa, on 16 February 1927 of British 1820 settlers. The family of her father Gerald Stocks hailed originally from South West England and established a drapers store in nearby Grahamstown. Her mother Edith (née Duffy) had a great grandfather John Duffy from Dublin.

The young Adelaine went to Port Alfred’s Queen Alexandra School and then as a boarder to Victoria Girls High School, Grahamstown. There she was elected a prefect and head of her schoolhouse. However, she was also known as a bit of a rebel, her eyes opened by discreet conversations with two left-wing teachers. One introduced her to the songs and film of Paul Robeson, the Afro-American singer-actor.

Brought up in Mentone, the modest home just upstream from Port Alfred on the banks of the Kowie River her father had built for his family of seven children, Adelaine was the second youngest. She had a happy childhood, swimming and playing with her sister Jo, a year younger.

After matriculating at 17, her first job was helping produce the weekly news sheet, the Kowie Announcer which her father edited, and where she learnt secretarial skills on the job. She also wrote popular news snippets about town events through the eyes of two fictional boys living in the small seaside town.

Adelaine then went to work for a building society in Pretoria where she met Walter Hain whose Glasgow-born parents had emigrated to South Africa in search of work after World War l. On 1 September 1948, she and Walter married in the Pretoria Registry Office.

The couple lived first in Pretoria and in Johannesburg (where Walter was completing his architectural degree). When he got his first job in Nairobi, Kenya, they flew there in a Dakota plane, Ad, as she was affectionately called, now heavily pregnant with their first child, Peter. In 1951, a year after he was born, they embarked on a hair-raising drive 3,000 miles from Nairobi to Pretoria through the heart of Africa, encountering many problems with their 1936 Lancia Aprilia: including regular punctures, tyre blow-outs and broken suspension springs. They ran out of cash and starved to feed their baby son, all the way wonderfully treated by African communities and white settlers.

Moving where Walter’s work took him, they lived successively in Port Elizabeth, Pietermaritzburg, Ladysmith and Pretoria. In 1956 they moved to England for two years, living in Ealing in London and then Ruckinge, Kent, before returning to Pretoria in 1958 to join the freedom struggle again until they were forced into exile in Putney, London in 1966.

Adelaine and Walter had had four children: Peter; Tom (born in Ladysmith in 1952); Jo-anne (born in Pretoria in 1954); and Sally (born in Kent in 1956).

By 2019 they had 11 grandchildren, 21 great-grandchildren and two great-great-grandchildren.

Ad became the matriarch of their extended family, maintaining contact across the world, through birthday cards, postcards then emails and texts. A prolific emailer until aged 90 and texter until aged 91, as a fanatical football fan she would always text results of her beloved Chelsea FC.

She was taught by her grandson Sam to operate a computer and aged 64 began working part-time in the House of Commons for Peter when he was elected an MP in 1991, a role she diligently continued until the age of 82.

She typed Wal’s many letters to the Guardian and Tribune newspapers editing these along the way as she had also done for him on her portable Olivetti typewriter for his many articles and letters in South African newspapers in the early 1960s.

Inseparable as a couple, both Walter and Adelaine had joined the South African Liberal Party in 1954 and from 1958 became extremely active in its Pretoria Branch, she its secretary and later he its chairman, until they were both issued with banning orders suppressing their activism.

Adelaine was the leading activist of the two in between caring for her four children while Walter was at work. A diminutive figure, barely five feet tall, she charged about Pretoria, the capital city and citadel of apartheid, fighting for civil rights. In local black townships like Atteridgeville, Lady Selborne and Mamelodi, she signed scores of passbooks to keep their owners from being arrested – even though it was illegal for her as their non-employer to do so.

Driving the couple’s old Volkswagen minibus, Ad became a familiar figure to local activists and to the security police. She patrolled Pretoria’s courts trying to discover teenage defendants who’d disappeared into the system and alert their frantic parents. One such defendant, 15-year-old Dikgang Moseneke, remembered her vividly in his memoirs as the only white person he’d ever encountered who gave him any support. She used to bring him a bar of his cherished chocolate every day until he was sentenced to 10 years on Robben Island. Having somehow studied for a law degree amid the harsh conditions on the Island, many decades later Moseneke become Deputy Chief Justice in the Constitutional Court, the country’s supreme court inaugurated by Nelson Mandela.

For their anti-apartheid activism in the Party, the couple was both imprisoned for two weeks without charge in 1961. They were released – but only because, as they were arrested, Ad had dashed away from Special Branch officers, chewed up and spat out the incriminating evidence, a draft leaflet supporting Mandela’s defiance campaign.

Isolated on her own in a large women’s prison, with warders creepily leering at her while she bathed, she was haunted by the cries of black women prisoners being savagely beaten.

Although the separately imprisoned Walter was sacked, they were undeterred. He got a new job and she was asked by the weekly anti-apartheid newspaper Contact to report on Nelson Mandela’s trial in 1962 in Pretoria’s Old Synagogue. Invariably the only person in the public gallery reserved for whites – the one for blacks was packed – Mandela on entry to the dock each morning would turn to her and raise his clenched fist in salute, to which she would stand and return with her small white fist raised.

They had both first met Mandela in 1958, taking lunch to him and co-defendants in the Treason Trial.

Then in 1963, by now notorious and regularly in the news, she was issued with a Magistrate’s letter warning her not to undertake any more “subversive activity”. She inquired as to what precisely this was and was told only that she would know. In another twist out of George Orwell, there was a cartoon in a national newspaper with the Police Minister instructing his head of security: “Go and find Adelaine Hain, check what she’s doing and tell her she mustn’t.”

Inevitably there was a knock on the door in September 1963 by a large Special Branch man who presented Adelaine with a banning order. Among a very long list of restrictions designed to stop her political activism and render her a non-person who could not be quoted in public, it made it illegal for her to communicate with any other banned person.

Which presented the apartheid government with an embarrassment they’d not encountered before when her husband Walter was banned a year later in 1964. They were issued with special new clauses in their banning orders allowing them – exceptionally – to communicate with one other banned person: namely each other.

But despite her banning order, she remained defiant, her activism now clandestine. Whereas before, she and Walter had together hosted parties for ambassadors to meet black activists in their living room, the banning order made it illegal for her to meet more than one other person at a time. So she sat in the kitchen and her eldest child Peter, then aged 13, brought each ambassador in one by one to talk to her.

She helped political prisoner Jimmy Makojaene escape over the border and she ingeniously smuggled in messages to others imprisoned, notably Hugh Lewin. Ad inserted these into orange piths or onion layers of food parcels, and into carefully unstitched bits of shirt collars of their clothes she washed. These formed an invaluable communications route.

When family and activist friend John Harris was arrested for planting a bomb on Johannesburg railway station in July 1964, she and Wal took in his wife Ann and baby David despite vehemently opposing his act of desperate resistance. Their duty to a friend came first. Harris had telephoned a 15-minute warning asking for the station concourse to be cleared. But that was deliberately ignored by security chiefs. The bomb killed an elderly woman, maimed her granddaughter and injured many others. The apartheid state exploited it to enforce even more terror. Soon with Mandela and other leaders on Robben Island, the resistance had been suppressed.

On 1 April 1965, Harris became the only white activist to be hanged among several hundred blacks in the anti-apartheid struggle; Ad with Wal organising his funeral, their 15-year old son Peter reading the address after they were both prevented from doing so by the police.

Eventually, in March 1966 they were forced to leave their beloved South Africa because Walter was deprived of earning an income after the government instructed all architectural firms in Pretoria municipality – to which they were both restricted by their banning orders – from employing him. The family moved to Britain where they lived in Putney for four decades.

On arriving in London they joined and became active in the Anti-Apartheid Movement, and within a few years found themselves playing a leading role in the militant Stop the Seventy Tour campaign led by their then 19-year old son Peter, which forced the cancellation of the 1970 all-white South African cricket tour to Britain. Its success propelled white South Africa into sporting isolation until apartheid was overthrown and Nelson Mandela became president. Ad was the de-facto secretary of the STST campaign, their small Putney flat turned into its headquarters. She joined demonstrations, plotted and organised.

In May 2009 she and Walter received a special award from Putney Labour Party for their activism when they moved to Peter’s parliamentary constituency of Neath, South Wales, living first in Clyne then Pontwalby, near youngest child Sally who with her own daughter Connie selflessly cared for them in their difficult latter years.

Walter died on 14 October 2016, leaving Adelaine utterly bereft for they had been inseparable in love, family, friendship and struggle.

There were formidable and brave women in the bitter long years of the anti-apartheid struggle. Icons like Winnie Mandela, Albertina Sisulu, Adelaide Tambo, Ruth First, Hilda Bernstein, Helen Joseph and Barbara Hogan, among many, many others.