Africa is the world’s second largest continent, both by size and number, after Asia. Its landmass holds 54 countries and nine territories. Over 1.11 billion people call Africa home and call themselves African. Africa, and being African, has become a core part of the identity of millions of the continent's inhabitants, but where does this word, to which so many have such an emotional connection, come from?

The exact origins of the word ‘Africa’ are contentious, but there is much about its history that is known. We know that the word ‘Africa’ was first used by the Romans to describe that part of the Carthaginian Empire which lies in present day Tunisia. When the Romans conquered Carthage in the second century BCE, giving them jurisdiction over most of North Africa, they divided North Africa into multiple provinces, amongst these there were Africa Pronconsularis (northern Tunisia) and Africa Nova (much of present-day Algeria, also called Numidia).

All historians agree that it was the Roman use of the term ‘Africa’ for parts of Tunisia and Northern Algeria which ultimately, almost 2000 years later, gave the continent its name. There is, however, no consensus amongst scholars as to why the Romans decided to call these provinces ‘Africa’. Over the years a small number of theories have gained traction.

One of the most popular suggestions for the origins of the term 'Africa' is that it is derived from the Roman name for a tribe living in the northern reaches of Tunisia, believed to possibly be the Berber people. The Romans variously named these people ‘Afri’, ‘Afer’ and ‘Ifir’. Some believe that ‘Africa’ is a contraction of ‘Africa terra’, meaning ‘the land of the Afri’. There is, however, no evidence in the primary sources that the term ‘Africa terra’ was used to describe the region, nor is there direct evidence that it is from the name ‘Afri’ that the Romans derived the term ‘Africa’.

In the early sixteenth century the famous medieval traveller and scholar Leo Africanus (al-Hasan ibn Muhammad al-Wazan), who had travelled across most of North Africa giving detailed accounts of all that he saw there, suggested that the name ‘Africa’ was derived from the Greek word ‘a-phrike’, meaning ‘without cold’, or ‘without horror’. In a similar line of thought, other historians have suggested that the Romans may have derived the name from the Latin word for sunny or hot, namely ‘aprica’. Where exactly the Romans got the name ‘Africa’ from is however still in dispute.

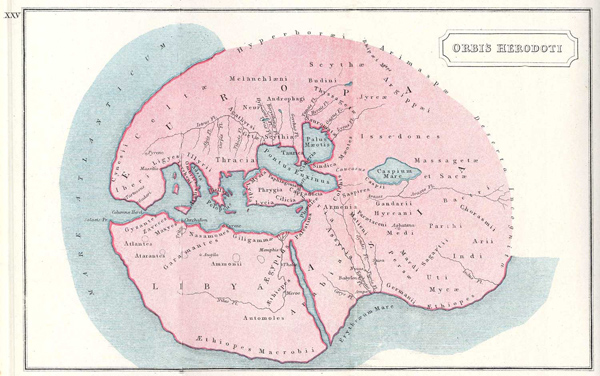

A reconstruction of Herodotus’ ( c. 484–425 BC) map of the world, showing North Africa marked as Libya. Image source: www.mlahanas.de

A reconstruction of Herodotus’ ( c. 484–425 BC) map of the world, showing North Africa marked as Libya. Image source: www.mlahanas.de

For most of its history, the Roman word ‘Africa’ was not used to describe the continent as a whole, but rather only a very small section of North Africa, what today constitutes the northern parts of Tunisia. Prior to the late sixteenth century, there were a variety of names used to describe the various constituent parts of the north half of Africa, with ‘Libya’, ‘Aethiopia’, ‘Sudan’ and ‘Guinea’ being by far the most common names used.

For the ancient Greeks, almost everything south of the Mediterranean Sea and west of the Nile was referred to as ‘Libya’. This was also the name given by the ancient Greeks to the Berber people who occupied most of that land. The ancient Greeks believed their world was divided into three greater ‘regions’, Europa, Asia and Libya, all centred around the Aegean Sea. They also believed that the dividing line between Libya and Asia was the Nile River, placing half of Egypt in Asia and the other half in Libya. For many centuries, even into the late medieval period, cartographers followed the Greek example, placing the Nile as the dividing line between the landmasses.

Early Arabic cartographers tended to follow the Greeks in the usage of their term ‘Libya’ for vast swathes of North Africa beyond Egypt. Later Arabic cartographers began to call the areas south of the Sahara, extending from the Senegal River to the Red Sea, Bilad al-Sudan, ‘the land of the blacks’, which is where the contemporary nation of Sudan gets its name from.

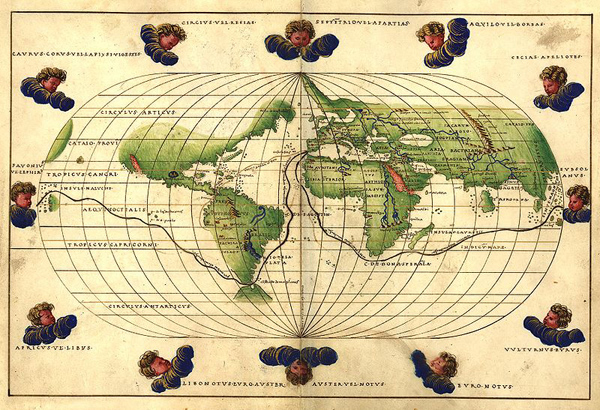

A seventh-century rendering of the divisions of the world in symbolic form. Printed in 1427 in Augsburg. Image source: wikipedia.org

A seventh-century rendering of the divisions of the world in symbolic form. Printed in 1427 in Augsburg. Image source: wikipedia.org

Some European cartographers, who tended to privilege Latinate derivations above others, preferred the Roman terms for the region, using the word Africa to designate the northern landmass, rather than the Greek term Libya, although Libya was still used by many. During the Middle Ages, the Christian cartographers adopted the Greek division of the world into three greater regions surrounding the Aegean Sea. The medieval cartographers, however, moved this understanding away from a geographical conception of the world into a more metaphorical understanding. They aligned each region to one of Abraham’s descendants, giving Asia to Shem, Europe to Japheth and Africa to Ham. This tripartite conception of the world was represented in extremely abstract and symbolic, rather than geographical, form, as is shown in the image above.

In the fifteenth century, after the Portuguese had rounded the Cape and made contact with the Christian Empire of Abyssinia, the Greek term Aethiopia, meaning ‘land of the dark-skinned or burnt’, which was used by Greek cartographers to designate the land below the Egypt and the Sahara, was revived again to loosely describe all of the tropical area of the continent below the Sahara.

World Map from the Portolan Atlas, 1544, showing only a small portion of North Africa marked as ‘Africa’. Image Source: wikipedia.org

World Map from the Portolan Atlas, 1544, showing only a small portion of North Africa marked as ‘Africa’. Image Source: wikipedia.org

At roughly the same time the Portuguese began to refer to all of West Africa below the Sahara as Guiné, the land inhabited by the Guinness people. Guinness was a generic term used for black people, in contrast to the more brown people of much of North Africa. The term Guiné, or the English Guinea, became ever more popular to describe the region of West Africa accessible from the Gulf of Guinea.

Until the mid-seventeenth century, the terms Guinea and Aethiopia, or Ethiopia, were popularly used to describe the lands south of the Sahara. Libya was commonly used for the North-West of Africa above the Sahara. Africa was used, sometimes instead of Libya, to denote the North-West of Africa, and sometimes alongside Libya to denote the central and northern region of Africa which today is predominantly occupied by Tunisia.

Before the late sixteenth century ‘Africa’ was used only to denote one part of the larger landmass that makes up the continent, primarily that area occupied by Tunisia and Morrocco. For most of its history, the continent of Africa as we know it today had many names for all its various constituents, none of which was used to describe the landmass as a whole.

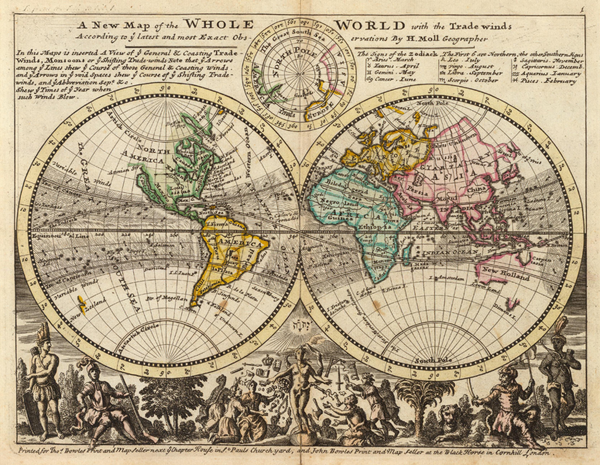

A map by Herman Moll from 1736 showing the world divided into continents, written in bold type, with Africa marked as the continent's name. Image Source: wikipedia.org

A map by Herman Moll from 1736 showing the world divided into continents, written in bold type, with Africa marked as the continent's name. Image Source: wikipedia.org

It was only in the sixteenth and seventeenth century, with the European age of exploration, that the concept of continents as contiguous landmasses bordered, and separated, by oceans, began to take shape. As European exploration opened up the idea of continents, so cartographers began to give single geographical names to entire continents. By the end of the seventeenth century, the name ‘Africa’ had won out over the others, beating names such as Guinea, Libya or Aethiopia to become the name for the entire continent as we know it today. Why Africa won out over all the other, often more popular, names is unclear, although some historians have argued that it is due to the seventeenth and eighteenth-century preference for latinate terms above all others.

The word ‘Africa’ has been a marker on the continent for millennia, but its dominance over the continent and its place as the name for all the people who live on it is only a very recent phenomenon.