Early years

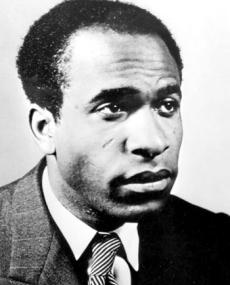

He was born on the 20 July 1925, in the Caribbean Island of Martinique. He was fifth of the eight children; his family belonged to the middle class. His family were descendants of African slaves who had been brought to the Caribbean to work on the sugar plantations. He lost his father Casimir in 1947, who was a customs inspector; his mother Eleanore Medelice resumed the responsibilities of the head of the house. To look after her family she opened a shop selling drapery and hardware. His mother was of the Alsatian origin, Frantz name reflected the Alsatian past. Her mother’s parents disapproved of her marriage to a man of darker colour. Frantz resembled his father’s skin colour as he was the darkest child in the family. Frantz was the least favourite of his mother’s children as he was considered she saw him as a troublemaker. It is said that Frantz did not had a good relationship with his mother, he felt alienated based on his skin colour.

Military career

At the age of 17 he sneaked away from home and sailed to the Caribbean Islandof Dominica, for adventure. From there he went to France to join the Free French Forces who were resisting the Nazi forces of Germany. While fighting for the French, he spent time in French-colonised Algeria. For his service he was awarded the Croix de Guerre, the French equivalent of the Purple Heart for bravery. While serving for the French military he experienced racism as he noticed that white French women refused to dance with Black soldiers who fought to free them from Nazi occupation.

Psychiatrist and Soldier

While serving in the army he managed to secure support for education in Psychiatry in Lyon, France. During his studies he attended Andre Leroi-Gourhan and Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s lectures in philosophy. He had an interest in wide range of readings such the works of Mauss, Heidegger, Levi-Strauss, Marx, Heggel, Lenin and Leon Trotsky, he also completed two plays, Loeil se Noie and Les Mains Parallels. It is where he met and married Marie Josephe Duble, a young White French woman of Corsican and Gypsy heritage , with whom he had a son. He also had a daughter from a previous relationship. Frantz wrote a thesis titled ‘The Desalination of the Black Man’ which was rejected, but it formed the foundation of his book titled ‘Black Skin, White Masks’.

He got his license, through training with the famous Spanish humanist psychiatrist Francois Tosquelles. He wanted to serve as director of any psychiatric ward in the French-speaking world. He applied to numerous institutions and was finally considered at the Blida-Joinville hospital in Algiers in Algeria. The racial discrimination continued, and in 1954 the Algerians rebelled against French repression; in response the French government used physical abuse against its subjects.

Activist and freedom fighter

These were the events which led to Frantz’ final stage of political radicalism, as the result he began secretly helping the rebel group called Front de la Liberation Nationale (FLN). He became more committed to the cause and later resigned from his post and became a full-time organiser and writer for the FLN. His involvement came with a great personal cost and he began to receive death threats from France.

In early 1957, he was exiled to Tunisia by the French colonial government. This move escalated his interest in political activism, which he pursued in Tunis and this made him popular amongst the locals. He became a mouthpiece for various African independence movements and travelled around the continent preaching the gospel of independence. Among his work was establishing a magazine called Moudjahid and being the ambassador for the Algerian rebel movement’s provisional government.

He trained FLN members in techniques for resisting torture and combat techniques he had learned from his years as a soldier. He eventually resigned from his post and became a full-time organiser and writer for the FLN. As a freedom fighter he travelled to their camps from Mali to Sahara, he gave refuge to other fighters and he trained nurses to dress wounds. In 1957 Fanon survived the slaughter, in which FLN killed 300 suspected supporters of a rival rebel group. He also survived an assassination attempt in Libya. In 1959 he was attacked on the border of Morocco and Algeria and was severely wounded.

Last years

By 1960, after completing a massive intelligence operation from Mali to Algeria he was diagnosed with leukaemia. In 1961 he went to the then Soviet Union for treatment and was informed that the best care available was in the United States of America. He then took the advice and went USA using a false identity under the name of Ibrahim Fanon. Upon his arrival in the US, Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) detained him for ten days without his treatment. He ended up contracting pneumonia which led to his death on 6 December 1961. His body was taken to Algeria where he obtained his citizenship. His body was welcomed and received a hero’s’ ceremony and military recognition as an important revolutionary and was buried in an FLN veteran’s graveyard.

His writings

· Black Skin, White Masks (1952), translation by Charles Lam Markman (1967)

· A Dying Colonialism (1959), translation by Haakon Chavalier (1959)

· The Wretched of the Earth (1961), translation Constance Farrington (1963)

· Toward the African Revolution (1964), translation by Haakon Chavalier (1969)