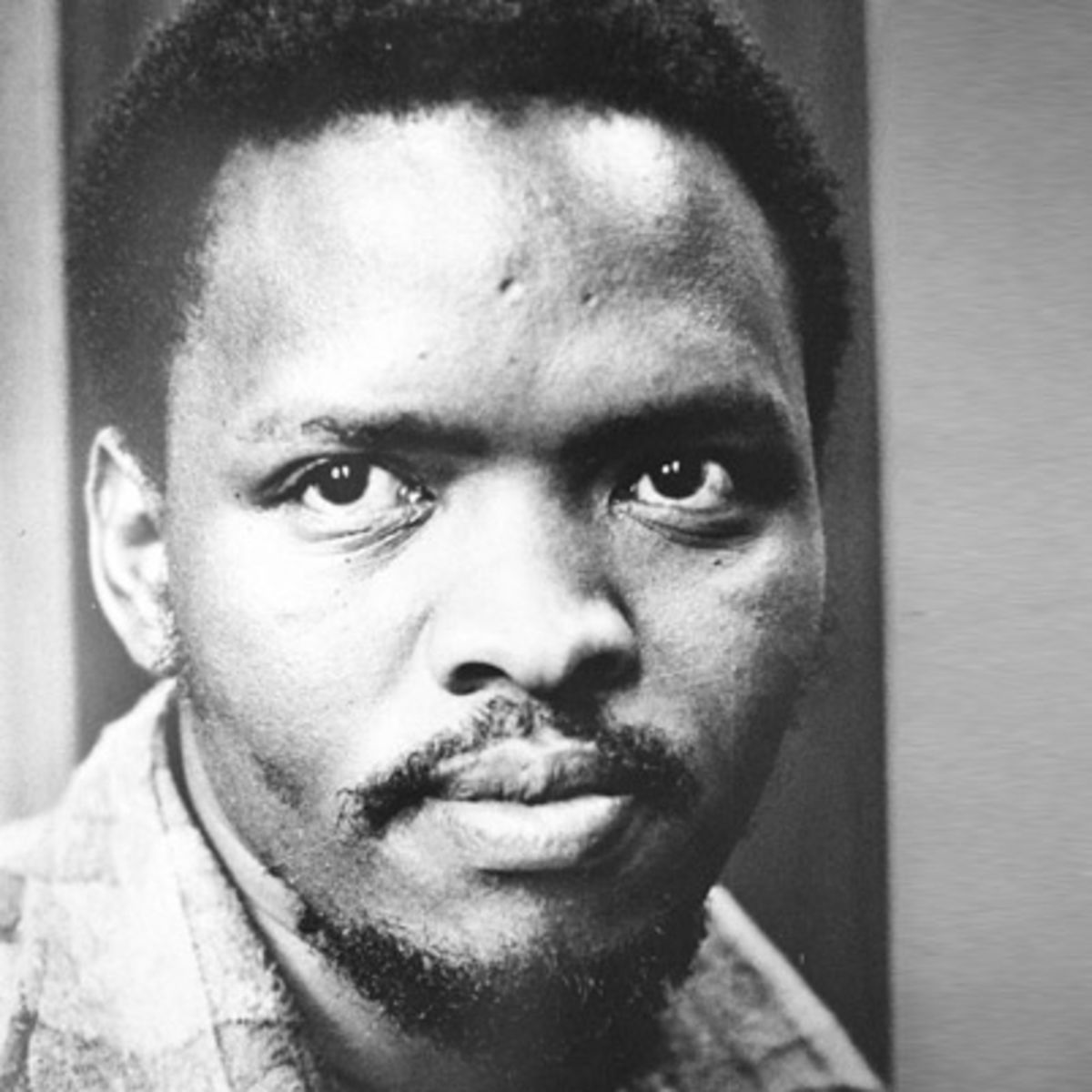

Bantu Steven Biko, leader of the South African Students' Organisation (SASO) and pioneer of the Black Consciousness philosophy, died in police custody at the age of thirty. Biko was arrested in the outskirts of Grahamstown on 18 August 1977. During his detention in a Port Elizabeth police cell he had been chained to a grill at night and left to lie in urine-soaked blankets. He had been stripped naked and kept in leg-irons for 48 hours in his cell. A blow in a scuffle with security police led to him suffering brain damage. Realising to a certain extent the seriousness of his condition, the police decided to transfer him to a prison hospital in Pretoria, which was 1133 km away. He died shortly after his arrival there.

His death was confirmed by the commissioner of police, General Gert Prinsloo. Due to local and international outcry his death prompted an inquest which innitialy did not adequately reveal the circumstances surrounding his death. At first, the South African Police denied having had anything to do with his death. They claimed that he might have injured his head after falling down, or that the injuries were self-inflicted with the aim of falsely accusing the police of brutality. The minister of police, Jimmie Kruger, claimed that Biko had died as result of a seven day hunger strike and that a district surgeon, called in on 7 September, could not find anything wrong.

Steve Biko was the 46th person to die in detention and his death drew worldwide condemnation of South Africa's detention practices and repressive laws. Two years later a South African Medical and Dental Council (SAMDC) disciplinary committee found there was no prima facie case against the two doctors who had treated Biko shortly before his death. Dissatisfied doctors, seeking another inquiry into the role of the medical authorities who had treated Biko shortly before his death, presented a petition to the SAMDC in February 1982, but this was rejected on the grounds that no new evidence had come to light.

Biko's death caught the attention of the international community, which increased the pressure on the South African government to abolish its detention policies and called for an international probe on the cause of his death. Even close allies of South Africa, Britain and the United States of America, expressed deep concern about the death of Biko. They also joined the increasing demand for an international probe. It took eight years and intense pressure before the South African Medical Council took disciplinary action.

On 30 January, 1985, the Pretoria Supreme Court ordered the SAMDC to hold an inquiry into the conduct of the two doctors who treated Steve Biko during the five days before he died. Judge President of the Transvaal, Justice W G Boshoff, said in a landmark judgment that there was prima facie evidence of improper or disgraceful conduct on the part of the "Biko" doctors in a professional respect. After South Africa's move to democracy, the police responsible for the death of Biko applied for amnesty to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). The police admitted beating Steve Biko severely, and lying about the date of his death, but maintained that it was accidental. The security police men were denied amnesty, because, according to the commission, Biko's death was not politically motivated. Biko's family objected to the TRC hearing, fearing that its amnesty policy would rob them of their right to justice.