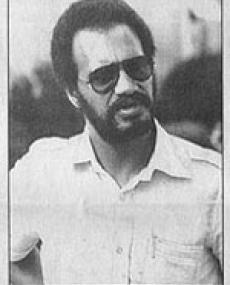

Peter Cyril Jones was born in 1950 on 7th of December in Somerset West in Western Cape. Jones after completing High School in 1976, he became politically active at the University of the Western Cape. He helped to launch the campus branch of the South African Students' Organisation (SASO), in 1970. This biography is an extract from a newspaper article on Peter Jones written by by Khuthala Nandipha for 'City Press', September 2007. "Biko’s comrade-in-arms still working to improve the lives of rural poor". I only heard of Steve’s death the day after the funeral, three weeks after his death,” Peter Jones remembers sadly. Steve Biko and Jones were arrested in Grahamstown, but separated in Port Elizabeth. Jones was held at the Algoa Park police cells. “Although I was very anxious during all this time and feared for the safety of some of the many comrades that were arrested after our own arrest, I did not for a moment think of Steve’s safety,” says Jones.' He just did not feature in my mind as a victim of any kind,” he adds. Hundreds of young protesters were arrested on returning home from Biko’s funeral.

Jones says he tried to speak to some detainees in a cell next to his. When they learnt that Jones was next door, he says, they started screaming until the police broke this up violently. It was then that Jones learnt that they had attended Biko’s funeral in King Williams Town. “Steve’s death left me with no words. I sat with what can only be described as a heavy blow to the chest: "a persistent pressure, an inconsolability persisting for many years,” he says. Jones and Biko, both members of the Black People’s Convention, were travelling together when they were arrested on August 18, 1977.They were returning form a meeting in Cape Town which had been cancelled, when they hit a road block in Grahamstown. Jones said that the Pan African Congress and African National Congress wanted to canvass support for unity across the liberation spectrum at the meeting. “Steve and I aborted the meeting after we arrived in Cape Town and several strange incidents happened, that made us feel very uneasy and unsafe.” Jones visited Biko’s friends and family in 1984 when his banning order expired. “I looked in the sad eyes of some of our friends and when I finally embraced Mamcethe, Steve’s mother, I just broke down." Biko was elected as honorary president and Jones the national secretary for economics and finance.

“Steve had a funny and happy demeanour ” says Jones. “He was serious and committed to his work for the people, like the rest of us. His capacity and fearlessness for people- all kinds, good ones or evil – was something to be experienced.” The two spent a lot of time with their political counterparts in King William’s Town. “Steve and I shared a somewhat frenetic interaction on a daily basis, but would have moments where we were able to be quiet with each other, in fellowship and reflective. “This would also occur in the wee hours of the morning, when the crowd had departed.”

Biko’s death did not deter Jones. He continued to strive for a better life for black people. He has since moved back to the Eastern Cape and is involved in a sustainable development and integrated rural village renewal program. Much like Biko, Jones is working on ensuring that communal lands, where the majority of poor South Africans live be turned into productive, economically functioning areas in the shortest possible time using self-reliance methodologies.