"Nothing Can Match the singleness of purpose, the foresight, or tenacity through all adversity, of Dulcie Howes ... She achieved in her lifetime what she set out to do: to present to her country ballet of a high standard technically and artistically; she also experienced the singular honour of receiving recognition both at home and abroad for her dedication she deserves it all." (From Marina Grut's book The History of Ballet in South Africa)

Dulcie was born in Little Brak in 1904, when "fancy dancing" was in its infancy in this country and it was not yet fashionable for virtually every wellbred little white girl to take ballet lessons, at least for a few years, to develop good posture, deportment and refinement of movement. Her early training was with Helen Webb and Helen White, but she furthered her studies abroad while in her late teens and early twenties, acquiring also an adequate grounding in ballroom, Spanish and Greek dance, and at the same time acquainting herself with the production of professional ballet. She returned to South Africa in 1928 to promote the art of classical ballet, relentlessly pursuing her dreams of giving the country its own worldclass professional company and making classical ballet accessible to all.

The establishment of her ballet school in Rondebosch and its incorporation into the music faculty of the University of Cape Town, in 1934, as the first dance department in the world to be linked to a tertiary institution, is well documented. Her ideas and beliefs in the value of a broad, dance based education were implemented at the UCT Ballet School in 1941 as a diploma course, but her ultimate goal of offering a degree programme at university level was only realised in 1998, some years after her death.

By all accounts never more than a competent performer, perhaps not an outstanding teacher of technique and, by her own admission, not a great choreographer, Howes nevertheless was able to inculcate a love of dance and theatre in others through the sheer enthusiasm and zeal with which she approached her mission. Her pupils included many internationally and locally recognised twentieth century dancers, producers, teachers and choreographers, such as John Cranko, Petrus Bosman, Pamela Chrimes, Alfred Rodrigues, Jasmine Honore, Johaar Mosaval, Richard Glasstone, Avril Bergen, Dudley Tomlinson and David Poole, whose skills as a producer, learned at Howes's elbow, are still sorely missed today. Furthermore her unique educational philosophy touched and changed the lives of many. Sadly, none of her own ballets was recorded for future generations, and only one, La Famille, was seen, in 1967, in the early repertoire of the Capab Ballet Company. However, her innovative work with local musicians and artists, such as Professor William Bell, John Dronsfield and Steven de Villiers, set a precedent for many of today's successful collaborations between choreographers, composers and designers.

Howes's vision as a facilitator resulted in classical ballet being taken by her UCT Ballet Company to all corners of South Africa and beyond its borders to Mozambique, Rhodesia, Zambia and South West Africa by rail and road, in circumstances under which no dancer would dream of travelling today. Such tours were continued into the early days of the three fully state subsidised professional ballet companies established within the arts councils of Pact, Capab and Napac, before they became too big and their productions too lavish and unwieldy to move from their designated performing spaces in Johannesburg, Cape Town and Durban. Howes's dancers were frequent visitors to tiny and remote towns accessible only along long and dusty roads, performing the classics and other ballets to wildly enthusiastic audiences starved of cultural entertainment and inspiring many to, at the very least, consider a career as a professional dancer.

Howes's own personal contribution to these tours, which ranged from organiser, administrator and coordinator through to ballet mistress, wardrobe and stage hand on occasion, is legendary. Today there is a growing and justifiable insistence by sponsors that companies seeking financial backing should serve all communities within a reasonable radius from their home base, to ensure access by all to the art form. The blueprint for touring is there, written by Howes, to be revisited more than thirty years later, and her contention that there is no bet ter training for a professional dancer than a tour to rural communities is equally valid today as it was in the early years of ballet in South Africa.

Howes, the administrator, was instrumental in the merging of the UCT Ballet Company into the Capab company in 1963, when it was decided, contrary to her and many others' recommendations, that there should be more than one professional company in a country with limited audience potential. Current moves by the two remaining professional ballet companies, Cape Town City Ballet and the State Theatre Ballet (previously Capab and Pact ballet companies respectively) to collaborate on an annual production and exchange repertoire and dancers regularly are in line with Howes's original thoughts on the danger of fragmenting the meagre and ever dwindling dance resources in the country.

Such was her reputation that very little was done on the professional dance scene without prior consultation with her, and her advice was sought when both the Nico Malan Opera House and the Baxter Theatre, the two foremost performing spaces in Cape Town, were conceived and built. A few years earlier, in 1961, it was her foresight that resulted in the construction of the new ballet studios at UCT. These still house the UCT School of Dance (renamed in 1997) and the newly independent Cape Town City Ballet. She was also much in demand on theatre administration boards around the country and widely respected as a judge and critic on numerous dance panels.

Howes worked indefatigably to establish ballet as a subject to be taught in schools in the four provinces of the old South Africa, and for many years was the custodian of the discipline in schools throughout the country, approving curricula and encouraging those whose teaching circumstances were not ideal. Sadly, the discipline is losing its appeal to scholars as a matriculation subject and is being replaced by a more general training in creative movement, contemporary and African dance. The aspirant classical ballet dancer has to rely increasingly on private tuition just to be exposed to the art form and certainly to attain the standard of technique required by a professional company.

On the political front Howes cut a formidable figure. It was as a dance educator that she was able to defy the politics of the day and ensure the inclusion of people of colour in her school and company. Her determination to provide a platform for all South Africans to participate in and appreciate classical ballet and her rigorous defence of her principles in the face of criticism enabled many that would otherwise not have had that opportunity to practice and participate in this magical art. She was always firmly but politely persuasive, and few had the courage to defy or gainsay a Howes edict. Some would attribute her success to arrogance and her ability to override anyone who stood in the way of her goals, but even her detractors are forced to admit, albeit grudgingly, that she changed the perception of audiences and artists alike of the role and relevance of a classical ballet training and the value of a professional ballet company to the cultural life of the country.

Howes's tangible legacy, the Dulcie Howes Trust, established by her and her husband, Guy Cronwright, in 1950, left this country's dance community a price less asset. Originally funded from the proceeds of performances given by the UCT Ballet Company, the Trust now relies solely on the generosity of the dance public, who are also being targeted to assist in keeping the professional company, Cape Town City Ballet, alive. Countless dancers, teachers, scholars and choreographers have benefited from the proceeds of Howes's work in financial terms, and many continue to receive assistance from the trust to pursue their dreams of contributing to dance in this country.

It was Howes who invited members of the EOAN Group, established in 1934 by Mrs H SoutherHolt, to complete their training at the UCT ballet school and it was the trust that provided the financial backing for this enterprise. The names of Didi Sydow, Gwen Michaels, Pauline Wicks and Johaar Mosaval stand out as beneficiaries of Howes's foresight in providing training and performing experience to members of the group. The Trust remains one of only two meaningful sources of bursaries for the study of ballet in the Western Cape.

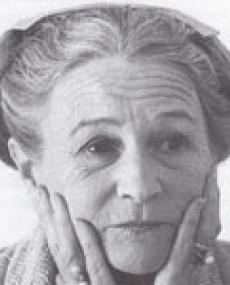

However, it is perhaps as a lady of glamour and style that Howes will be most fondly remembered. Who can forget the sight of her diminutive figure, clad in a tapestry of colour, in gold or in silver, sweeping into an auditorium or gracing a stage and how many of us did not appreciate her succinct and witty vocal delivery, sometimes on more serious occasions bringing us all back down to earth where her feet were always firmly planted, and making her much in demand as a public speaker. She constantly reminded us of the beauty of classical ballet, its value as an educational tool and physical training method and its ability to transport the viewer into a world of fantasy and awe inspiring physicality far removed from the ugliness and depression of our daily existence.

She may well just have been in the right place at the right time, but it was her firm intent and unshakeable belief that classical ballet would always have a place on the South African stage that provided the infrastructures and opportunities for the development of the art. Many of these are being slowly eroded and it is left to the present generation to protect and preserve the beauty of classical ballet, a priceless heritage left to the South African cultural scene by Dulcie Howes.