Dingane ka Senzangakhona was born in 1795 to father Chief Senzangakhona and mother Mpikase kaMlilela Ngobese who was Senzangakhona's sixth and ‘great wife'. [i] Chief Senzangakhona married sixteen women in total and had fourteen known sons, daughters however were not recorded. Very little is known or recorded about Dingane’s childhood or early career. Instead, Dingane enters the record when on the 22 of September 1828 he, with the assistance of his half-brother Mhlangana and servant Mbopha, assassinated his brother and the then Chief of the Zulu – Shaka Zulu. Shaka, the son of Chief Senzangakhona’s third wife, had seized the Zulu chieftainship in 1816, and had thereafter extended the Zulu kingdom. Soon after the murder of Shaka, Dingane had his half-brother Mhlangana murdered and thus rose to the position of Chief of the Zulu. Dingane moved the royal homestead from Nobamba in the emaKhosini valley to a new inland location which he called Mgungundlovu from which he reigned until 1840.

Following the death of both Shaka and Mhlangana and Dingane’s subsequent rise to power messages were relayed to neighbouring dependencies, such as the Europeans of Port Natal, to notify them of the change and assure them that the Zulu’s newest Chief was inclined towards peace and would not harm them. [ii] Shaka’s ‘grand army’ at the time was in the north and was due to return shortly to receive the news of their leaders death. Dingane thus recognised the need to assemble his own military support. Since the majority of Zulu men of military age were up north serving in the ‘grand army’ he had little option but to utilize the menials and herdboys who eventually formed the basis of his home guard regiment which he called uHlomendlini, meaning ‘this which is armed at home’. [iii] The regiment comprised of two companies, the younger men being in the Mnyama (black) section and the older men in the Mhlophe (white) section. Dingane was thus well prepared for the eventual return of the Zulu army who received the news in stunned silence. The warriors were promised peace, a life of ease and the enjoyment of their booty. Furthermore, they were promised the right to marry. The majority of the troops accepted these conditions and bowed to Dingane. The marshal of the army, Mdlaka, however objected. Mdlaka was subsequently strangled in his hut and succeeded by Ndlela as army general.

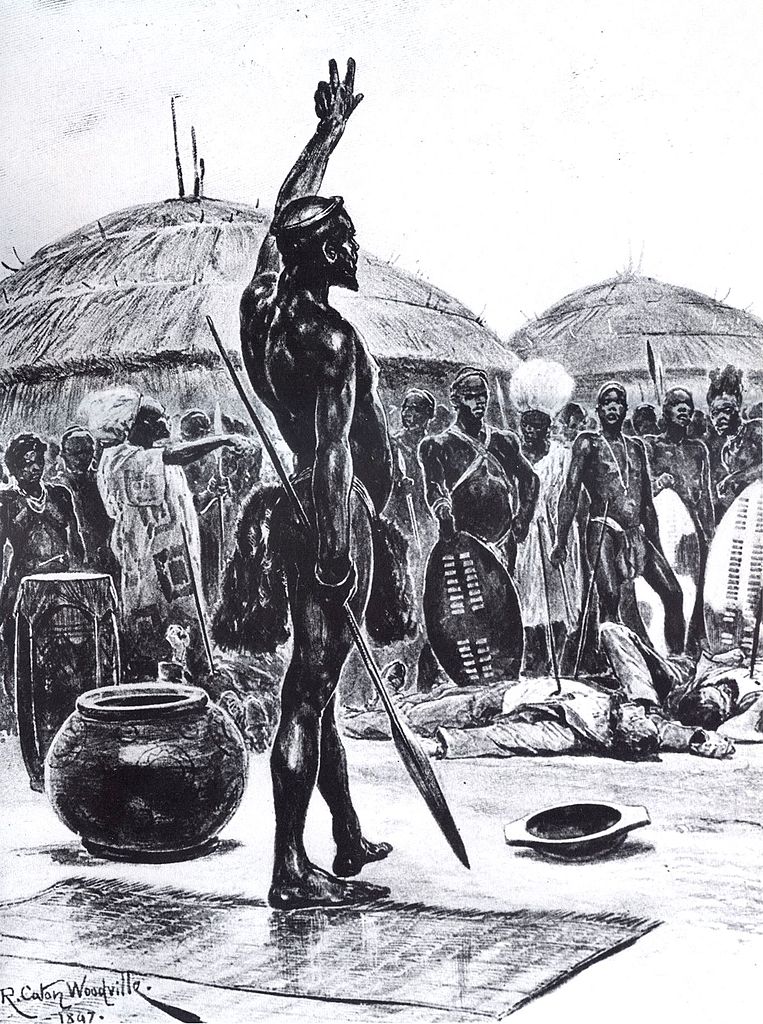

‘Dingane orders the killing of Piet Retief's party of Voortrekkers’ by Richard Caton Woodville, Jr. Source: Suid-Afrikaanse Geskiedenis in Beeld (1989) by Anthony Preston. Bion Books: Printed in South Africa.

‘Dingane orders the killing of Piet Retief's party of Voortrekkers’ by Richard Caton Woodville, Jr. Source: Suid-Afrikaanse Geskiedenis in Beeld (1989) by Anthony Preston. Bion Books: Printed in South Africa.

In 1829, shortly after consolidating his power, Dingane oversaw the relocation of the Zulu capital from the hut-city of Dukuza to the traditional Zulu valley near the Mkhumbane stream. This new capital he renamed Mgungundlovu, meaning ‘the secret plot of the elephant’, which referred to his own plot to assassinate Shaka. William Wood, interpreter to Zululand missionary Reverend Francis Owen, described Mgungundlovu as it was then:

“The form of Dingane’s kraal was a circle, it was strongly fenced with bushes and had two entrances. The principal one faced the king’s huts, which were placed at the furthest extremity of the kraal, behind which were his wives’ huts. These extended beyond the circle which formed the kraal, but were also strongly fenced in. On the right-hand side of the principal entrance were placed the huts of Ndlela (Dingane’s captain) and his warriors; and on the left, those of Dambuza (another of his captains) with his men. The kraal contained four cattle kraals which were also strongly fenced and four huts erected on poles which contained the arms of the troops.” [iv]

It is recorded that with Dingane in power, increased prosperity actually came to Zululand. The warriors of the Zulu army, who were now able to marry and set up their own homesteads, were gifted cattle and were thus able to settle down and enjoy the fruits of their victories – ‘a country bulging with looted cattle and captured women, who were set to work to till the fields and produce military reinforcements.’ [v]

During his reign, Dingane was increasingly involved in trading activities with many of the Portuguese traders from early Port Natal. When on 18 February 1829, Dr Alexander Cowie, a former surgeon from the Cape, and Benjamin Green, a Grahamstown merchant, arrived at Dingane’s Nobamba kraal, they were met by a party of about forty Portuguese traders. The Portuguese traders had reportedly been visiting Dingane in an attempt to re-open trading relations and pay their respects to the Chief of the Zulus. Dingane was known to have on many instances traded heads of cattle and hides in exchange for rifles and gunpowder. On a trading expedition to the Zulus a trader by the name of Isaacs noted Dingane’s respect for both firearms and Europeans:

‘He at once acknowledged it to be his opinion that no power he had could combat with another that used firearms; but added, he did not believe any people could conquer the Zulus excepting Europeans.’ [vi]

"Dingane in Ordinary and Dancing Dresses", by Captain Allen Francis Gardiner. Source: Allen Francis Gardiner - "Stamme & Ryke", deur J.S. Bergh, in samewerking met A.P. Bergh. Don Nelson: Kaapstad. 1984.

"Dingane in Ordinary and Dancing Dresses", by Captain Allen Francis Gardiner. Source: Allen Francis Gardiner - "Stamme & Ryke", deur J.S. Bergh, in samewerking met A.P. Bergh. Don Nelson: Kaapstad. 1984.

Fearing the devastation that could follow a potential military clash with Europeans, as early as 1830, Dingane sent an expedition to the Cape in an attempt to establish good relations with the British. On 21 November 1830 the group reached Grahamstown and presented four tusks to the Civil Commissioner. John Cane, Dingane’s ambassador, relayed the message that Dingane wanted to live in peace with his neighbours, that he wished to encourage trade and would protect traders, and that he desired a missionary.

In January 1832, the government at the Cape finally showed an interest in the affairs of Zululand and sent a well-known explorer Doctor Andrew Smith to investigate more. Smith was well received by Dingane and entertained him with his beautifully dressed women and dancing warriors. Upon his return to the Cape, Smith was reportedly very enthusiastic about Natal and boasted about the greenness and fertility of the region. Thus, in early 1834, the farmers of the Grahamstown and Uitenage region organized a so-called ‘commission trek’ to visit Natal and consider settlement. Twenty-one men and one women, using fourteen wagons, traversed the Natal midlands led by a certain Petrus Lafras Uys. [vii] Nearing the region of Dingane’s capital, the group sent a man named Richard King to meet with Dingane in person and request land. Dingane received the request with interest but demanded that the commission members themselves visit him. There seemed to be countless different obstacles which hindered the commission members from visiting Dingane personally. Uys himself was down with a fever and subsequently sent his younger brother, Johannes Uys, to meet with Dingane. Johannes soon returned with a report that Dingane had allegedly indicated that Natal was vacant and available for European settlement.

Dingane and the Voortrekkers

An illustration of Dingane’s Kraal by Margaret Cary Image source

An illustration of Dingane’s Kraal by Margaret Cary Image source

It was only in 1837 however, with the arrival of the Voortrekkers into the Natal region, that these negotiations would come to fruition. In October 1837 the group of Voortrekkers led by Piet Retief reached Port Natal where they were welcomed by the British ivory traders who occupied the area. On 19 October Retief sent a letter to Dingane as a sign of peace and to inform him that he’d be coming up to Mgungundlovu to discuss the question of land.

Retief and the Voortrekkers described Dingane as a:

'robust, fat man, but well proportioned and with the regular features of a well-bred Zulu. There was nothing at all forbidding in his appearance. He was always smiling and was scrupulously clean, being well scrubbed every morning by some of his women in the royal bath, a depression in the ground near his hut. He was shaved every day as well. He hated hair on his head, and one of his women kept him as bald and clean-shaven as a new-born babe, by means of an exceedingly sharp axe. After his toilet, and being well rubbed with fat, he generally spent his day sitting in an armchair attending to business, drinking beer and playing with any new gew-gaws some European visitor might have given him, such as a telescope to watch his people around the kraal, or a magnifying glass to burn holes in the arms of his servants.’ [viii]

Upon his arrival, Dingane entertained Retief and his men with dances, feasts and sham fights and discussions regarding the allocation of land commenced. From this point on sources differ greatly. Dingane supposedly declared that he was prepared to grant Retief an extensive area between the Tugela and the Umzimvubu as well as the Drakensberg, on condition that Retief restored to Dingane the cattle stolen from him by Sikonyela (the Tlokwa chief). Dingane felt that this would prove to him that Sikonyela and not the Voortrekkers had in fact stolen the cattle. Some sources claim that Dingane also demanded rifles. With the wisdom of hindsight, it seems that Retief was incredibly naive in his dealings with Dingane. What is also evident is that Dingane had experienced more than enough trouble from the handful of whites at Port Natal and probably never had any intention of allowing a large amount of heavily armed farmers to settle permanently in his immediate neighbourhood.

The Voortrekkers obtained the cattle from the Sikonyela as per the deal with Dingane. Retief surrendered the cattle but refused to hand over the horses and the guns he had taken from the Tlokwa. In the meantime, however, Dingane’s agents, who had accompanied Retief to supervise the return of the cattle, reported that even before the land claim had been signed, Voortrekkers were streaming down the Drakensburg passes in large numbers. These allegations allegedly fueled a mistrust between Retief and Dingane. On the 6 February Dingane requested that Retief and his men visit his royal kraal without their guns to drink beer as a farewell gesture. This request was strictly in accordance with Zulu protocol - that nobody appeared armed before the King. Retief suspected no foul play and accepted the invitation. As soon as the Voortrekker party was inside the royal kraal, Dingane gave the order and his regiments overpowered Retief and his men, and took them up to a hill to be executed. Dingane subsequently sent out his warriors to kill the rest of the Voortrekkers awaiting Retief's return from Mgungundlovu. Hundreds of Voortrekkers were consequently killed at Bloukrans and Moordspruit which set off months of bloody conflict between the Voortrekkers and Dingane's Zulus.

In response, Voortrekker leaders Hendrik Potgieter and Piet Uys sent out an expedition against Dingane, but were defeated at Italeni. The conflict culminated in the battle at the Ngome River on 16 December 1838, in which the Zulus suffered a severe defeat. The Ngome River was subsequently renamed Bloedriver or Blood River, referring to the deep red colour of the river filled with Zulu blood. The incident became known as the Battle of Blood River.

Led by new Voortrekker leader Andries Pretorius, a Voortrekker commando went to Mgungundlovu to confront Dingane. But Dingane had burned down his whole kraal and the Zulus launched an attack on the command at the White Umfolozi River. In the meantime, the British occupied Port Natal (now Durban). From there, they advanced on Dingane, but were defeated at the Tugela River. Dingane's warriors also attacked the settlement at Port Natal.

In September 1839, another half-brother of Dingane, Mpande, defected with many followers to Natal. There, the Voortrekkers recognised his as the ‘Prince of the Emigrant Zulus'. On Christmas Eve 1839, the British garrison withdrew from Port Natal. Almost at once, the Voortrekkers hoisted the flag of the Republic of Natalia and made an alliance with Mpande's supporters to make a joint attack on Dingane. In February 1840, Mpande's forces finally decisively defeated Dingane on the Maqongqo hills. He fled north across the Phongolo River, where it is believed he met his death in the Lebombo Mountains at the hands of the Nyawo and his old enemy, the Swazi.

An annotated diagram of Dingane’s Kraal. Image source

An annotated diagram of Dingane’s Kraal. Image source

Endnotes

[i] Okoye, Felix. ‘Dingane: A reappraisal’ in The Journal of African History, Vol. 10, No. 2 (1969) ↵

[ii] Bulpin, T.V. Natal and the Zulu Country. (Pretoria: Protea Book House, 2013) ↵

[iii] Ibid. ↵

[iv] Ibid, pg. 146. ↵

[v] ibid, pg. 112. ↵

[vi] Ibid, pg. 118. ↵

[vii] Ibid. ↵

[viii] Ibid, pg. 147. ↵