Published date

Related Collections from the Archive

The artworks presented in this section of the exhibition had their historical beginnings in the decades of the 1920s and 1930s. These beginnings took place in two distinct localities, in the rural areas, where men and women were engaged in a variety of crafts, and the urban centres, where a new educated elite began exploring western approaches to art. What they had in common was an historical connection with rural life and African traditions, a cultural and educational influence from Europe, and the imposition of an economic system controlled by whites. They differed in terms of the kinds of educational and cultural opportunities available. Rural culture was essentially tied to nature, and social and religious traditions had been significantly challenged by the spread of Christianity. On the other hand people living in the slum yards. Ghettoes and townships of the urban areas were exposed to a cosmopolitan culture, with American culture as an increasing influence.

The twenties was a period when large influxes of population into the cities, coupled with a singular lack of organised entertainment, helped swell the number of shebeens in these cities and European and American rag and jazz became the rage for both black and white. (1) These were times of enormous change and movement of people from the countryside into the cities. H. I. E. Dhlomo (1903-1956), a prolific poet and playwright, reflects upon the duality of African culture at this point. There is no single African point of view... There are urban and rural Africans; tribal and detribalised Africans. We have the problem of religion, which, from the national point of view, is a dividing force. There is also the question of literacy and illiteracy. (2) Hence the pioneers of twentieth century art by black South Africans arise out of three distinct yet interconnected streams: those living and working in the countryside (e.g. Tivenyanga Qwahe), those living and working in the cities (e.g. John Koenakeefe Mohl) and those constantly moving between these two localities (e.g. Gerard Bhengu). A significant amount of the work dating from this period is found in various cultural history museums or in private collections. One would need to visit the Africana Museum in Johannesburg, the Killie Campbell Africana Library in Durban and many others, to see a great deal of the art by black artists of the early part of this century. Almost all the major public art collections, on the other hand, include nothing by black artists prior to the work of Gerard Sekoto. The history of the Pioneers can he understood in terms of three broad concepts: changes in material conditions, new-forms of patronage and the introduction of new educational values.

The growing capitalist system had a direct impact on tribal traditions, undermining and transforming them. By the 1930s taxes had been imposed on all chiefdoms in South Africa, driving more and more people into wage labour. (3) It became essential for black people to enter into the cash economy in order to pay their taxes. Hence they were compelled to sell their labour or, if they were sufficiently skilled, the products of their labour. In fact employment as an artist/craftsman was one way of avoiding wage labour and retaining the freedom to work at home.

Apart from the economic pressures, many parts of the country had been devastated by droughts during the early 1930s, an account of the early development of the work Samuel Makoanyane reflects the conditions that confronted black people generally in the rural areas.

During this period, many Basuto, who were in the habit of eking out their liveliÂhood by the manufacture of sundry native crafts, intensified their efforts and others turned to it as a means of earning a few shillings. They hawked their wares in the various camps in the territory and the townÂships across the border, some even going further afield than this and travelling by train to reach their markets. As a general rule the men produced grass baskets and hats and the women manufactured various types of clay pottery.

As mentioned, it was usually the women who worked in clay, but among the few exceptions to this was a young man named Samuel Makoanyane. (4) During the 1920s Oswald Fynney, Chief Magistral Zululand, recognising the importance of existing traditions, sent runners out to scout for wood-carvel According to Rebecca Hourwich Reyher, the Qwabe Brothers produced a keen collector at that time, the very best work .was produced by the Qwabe Brothers (6)

Through this process of engagement between traditional craftsmen and the white economy changes in the nature and purpose of these craft activities occurred. One might suggest that it was the process of entering into the white market that resulted in the designation being applied to particular craftsmen. There is a difference however between the history of someone like Tivem, Qwabe, who was a craftsman, producing various fund carved objects for his community, and Makoanyane, from a very young age produced clay figures for a market. Qwabe and his two brothers were "commissioned" by members of their own community to carve amongst things, wooden dolls, and walking sticks and mat racks for storage of grass sleeping mats. They also recognised the potential for selling these objects to a white market and did so at the agricultural shows convened in Durban. On the other hand Makoanyane and Hezekiel Ntuli were "commissioned" from the early age of seventeen, in both can make clay sculptures for the white tourist market. Mayane does not appear to have worked for his community and apart from teaching young children model in clay, the greatest amount of Ntuli's labour directed at the white tourist market.

What is apparent is that there were now two distinct outlets for crafted objects: a community-based market for functional objects and a white market for curie artworks.

The role of the church, agricultural shows, the commercial curio market and the professional fine art were all contributing forces in this white patronage and in the development of new forms of artistic activity and black craftsmen/artists. The agricultural shows in Durban became an important marketplace for a number of black craftsmen. From 1937 until 1959, Tivenyanga Qwabe and numerous other carvers displayed and sold their carvings at these she a newspaper article dating from 1937 Rebecca Hoi Reyher explains why a carver by the name of Abenig came to work as a fulltime carver: Zulu showed me his work ... and told me that when he saw what I had paid the Qwabes for their work ten years ago he decided that from then on he would be a carver and nothing else. (7)

The mat rack holders, made by Tivenyanga Qwabe from boxwood and any other available timber (and timber was scarce), were ideally adaptable for sale to a white market. He could not satisfy the demand from curio shops for the decorated panels that formed the front of the mat rack holders. They were made with the aid of a pocketknife only and burnt so as to create the symbolic relief patterns. These were dismantled by the shopkeepers and sold as ' pictures'. It would appear that Qwabe, Makoanyane and Hezekiel Ntuli were unable to meet the demand for their work. This led to a mass-production of popular pieces by Ntuli and Makoanyane. Makoanyane made hundreds of identical pieces. For example, the works owned by the Killie Campbell Africana Library (Durban), the Africana Museum (Johannesburg) and the National Cultural History and Open Air Museum (Pretoria) are all almost identica l representations of his grandfather, Makoanyane, who was a warrior under Chief Moshesh. It is for this reason that a great deal of the work from the rural areas was dismissed as ' banal souvenirs for the tourist trade '. (8) The fine and tradition demands the creation of unique and individualized pieces whereas the curio market thrives upon mass-produced objects. However, an assessment of the production of these artists/craftsmen reveals works of exceptional quality.

Makoanyane Samuel (1904 - 1964)

Makoanyane Samuel (1904 - 1964)

Warrior

These objects are not only important in their own right but also enormously significant for the understanding of later developments in the history of South African. For example the relief carvings of Qwabe are an impo rt ant precedent for the relief printing that developed at the c. angelical Lutheran Centre for Art and Craft at Rorke's Drift in the 1960s. The miniature clay figures of Makoanyane, produc e d in the 1930s, can be juxtaposed with the carved miniatures of Johannes Segogela in the 1980s.

The subject matter of most of this early work, and that includes the watercolors of Gerard Bhengu, was essentially the portrayal of African life and customs. White artists popularize this fitted fairly comfortably into the current as well at that time. There existed an enormous demand for depictions of 'indigenous' scenes. African subjects and the South African landscape were popular.

...this parochialistic view of art was encouraged by such well-intentioned devices as the Karl Gundlefinger Award, which had been inaugurated by the NSA [Natal Society of Arts] in 1926 for the purpose of promoting painting 'descriptive of the domestic or tribal life, or the customs of South African Natives'. (9)

One example of such work was the mural painted in South Africa House, London by Eleanor Esmonde-White and Leroux Smith Leroux who painted scenes "symbolical of the natural and supernatural elements in the lives of the Zulus before their contact with the Europeans". (10) Virtually all of these early black artists received commissions from white patrons for works that accurat e portrayed particular African personages, e.g. sangomas, people in traditional dress, and rural scenes. At tim e s this limited the kind of work produced. An instance of this relates to the patronage of Samuel Makoanyane by C. G. Damant: About this time he produced a few figures modeled from Europeans... They excited some interest b ecause the likeÂnesses were very good, but I felt constrained to advise Samuel against this type of work, pointing out to him that, to really establish himself, he should produce models of his own people, in their various daily occupations... I lectured him continually on the desirability of turning out likenesses of the men and women he saw about him, in his village and in the fields. I was certain that there would be a constant and growing demand for this and I was proved entirely correct. Samuel saw the point and followed the advice; he ceased to make any more European figures and settled down to making various types of Basuto, for which he became known far and wide. (11)

A similar kind of prescriptiveness and a desire to keep the artist 'tribal' and untainted b y outside influence is reiterated time and time again. John Koenakeefe Mohl who had traveled to Germany and studied art during the 1920s, described a similar incident to Tim Couzens: Mohl was once approached by a white admirer and advised not to concentrate on landscape painting but to paint figures of his people in poverty and misery. LandÂscape, he was advised, had become a field where Europeans had specialized and they had advanced very far in perfecting its painting. In a humble voice and manner humbler still, he smilingly replied: ' But I am an African and when God made Africa, He also created beautiful landscapes for Africans to admire and paint. '( 12)

Hence two different stand a rds were applied to black and white artists. This was in keeping with the prevailing view that education for black people should remain distinct and separate. far more formal education than Qwabe, Ntuli or Makoanyane. As urban artists they gained access to new materials and processes and to a new language of art making.

Mohl John Koenakeefe (1903-1985) Mid winter

Mohl John Koenakeefe (1903-1985) Mid winter

[In the 1920s] Dr. C. T. Loram was Natal's first Chief Inspector for Native Education. He was a strong advocate of 'practical' education for the blacks and also coined the phrase that blacks should ' develop along their own lines'. This idea of a separate kind of education for blacks did not catch on until the Bantu Education Act of 1953 but it was very much part of the education debate of the time. (13)

The desire to keep artists 'unspoilt' is a recurring theme throughout the history of the art of black South Africans. This kind of attitude is well illustrated in the case of Hezekiel Ntuli. Dr. J. E. Holloway, Chairman of the Native Economic Commission (1930), and a great admirer of Ntuli, had this comment for the 17-year-old prodigy: You will have to be careful that Hezekiel does not come under the influence of tutors who will so concentrate on the perfecting of his artistic abilities that his uncanny instinct for putting life into his models will be eliminated. (14)

However there were those who believed that a formal art education was beneficial. An occurrence that offers a different perspective on the education debate was the encounter between Gerard Sekoto and George Pemba, who both submitted work to the May Esther Bedford An Competition of 1937. A newspaper article at that time reported the outcome thus:

First prize (20 pounds): Mr. G. Pember, King Williamstown.

Second prize (5 pounds): Mr. G. Sekoto, Khaiso Secondary School, and Pietersburg.

There were six entrants and although this number is small it is by no means surprising when it is borne in mind that the development of art among the Bantu does not receive much encouragement even in Bantu schools.

Professor Winter-Moore and Mrs. Bates, both of the Art School, Rhodes University College, Grahamstown, were the judges, with the help of a grant from the Bantu Welfare Trust, Mr. Pember has been receivÂing training at the Art School, Rhodes University College Grahamstown. (15)

It is interesting to note that in his recent correspondence with Barbara Lindop, Sekoto comments on the fact that the judges had favoured the 'schooled' artist Pemba over the 'self - taught' artist Sekoto. Little did Sekoto realise that those very judges were Pemba's teachers.

Unknown Artist - Ox

Unknown Artist - Ox

Gerard Sekoto and John Koenakeefe Mohl both talked of how the source of their art making derived from their childhood activities: modeling clay oxen at the riverside. Mohl and Sekoto, as well as Ernest Mancoba and George Pemba had all received Mohl and Sekoto as well as Mancoba, felt drawn to Europe, and they went in the search for knowledge and art education. It was common for artists from many parts of the world to make a pilgrimage to Paris, but there were patrons who advised against this for black artists, as occurred with Pemba. Pemba had wanted to travel abroad, and recalls being advised against this by white friends "who said I'd get mixed up with the wrong people and communists and come back frustrated. "( 17)

Gerard Bhengu was denied the chance to acquire formal art training. He, like Pemba, began his childhood in an environment in which pens or pencils, let alone paints and brushes, were simply not available. Hence their earliest experiments in drawing involved the use of charcoal from the cooking fire, using walls as the drawing surface. A certain Dr. Kohler discovered Bhengu's talents, who provided Bhengu with paints, brushes and paper, as well as a number of reproductions by Old Masters to copy. Dr. Kohler also encouraged Bhengu to seek his models from life in the village. According to Phyllis Savory, who produced a publication illustrated by Bhengu, he lost his creative impetus when Dr. Kohler left. A suggestion by Dr. 0. McMalcolm (Chief Inspector of Native Education) that Bhengu should undergo proper formal training was ostensibly turned down by the Department of Fine Arts at the University of Natal.

The Professor however, advised strongly against this, suggesting rather that he be encouraged to work in his own way and develop his own technique. (18)

However although the opportunities for art education for black South Africans were extremely limited in the 1930s and 1940s, there were a number of mission schools which offered art classes; for example the Diocesan Training Center at Pietersburg and the Mission College at Mapumulo. In most cases this involved the production of ecclesiastical carvings for use in the churches.

During the 1940s the 'art' tuition that did begin to take place concentrated almost exclusively on craft. Jack Grossert, Inspector of Arts and Crafts for the Zulu schools in the Natal Education Department, undertook pioneering work in the field of black art education during the forties and fifties. He established an art teachers training course at Ndaleni Training College near Richmond in Natal.

The course was started by Mr. Grossert in the late 1940s in order to improve the quality of art teaching in primary schools. At that time it was noticeable that traditional craftwork such as beadwork, carved wooden spoons or trays... formed the greater part of the work done in art lessons. (19)

Loma Pierson (principal of Ndaleni for eighteen years) goes on to conclude that although a lot of this work was technically good, it failed to challenge the intellectual, creative and expressive needs of the teachers and pupils. During her employment at Ndaleni in the 1960s she developed a curriculum, which taught the history of western and African art and exposed students to western media and techniques. However the art training that was offered to students at some of the mission colleges such as the Diocesan Training Centre in Pietersburg laid the foundations for a new genÂeration of black fine artists. At first the carving undertaken at this centre was within the confines of an ecclesiastical art. Artists such as Mancoba soon moved into more personalized and secular forms of creative expression.

Some of the work produced at the mission colleges such as the Diocesan Training centre in Pietersburg, and at St. Peters Secondary School, Rosettenville, Johannesburg, was submitted for exhibition and in this way Sekoto, Mancoba and a number of other artists were exposed to the white art establishment.

The earliest records of black artists exhibiting as professional fine artists are to be found in the catalogues of the South African Academy Exhibitions. (20) Right from its inception the South African Academy included a wide range of exhibits. Architectural drawings, craftwork, applied art and fine art were all exhibited in terms of distinct categories, which included ' general', 'student ' and 'native exhibits' categories. It is important to note that those black artists whose artwork gained entry to these exhibitions did so with the assistance of some or other white philanthropist. The earliest available record of a black participant can be dated to the eleventh annual exhibition, which took place in 1930 at the Selbourne Hall, Johannesburg. This took the form of a 'Special Exhibit by Native Artist ', and eight works of Moses Tladi (Tlali) were shown, two oils and six pencil drawings. Little more is known about Tladi other than a short reference to him by Tim Couzens:

Amongst the earliest painters were those who were self-taught. One was a gardener called Moses Tladi, a 'native genius' as Umteteli [ Umteteli wa Bantu: a newspaper] described him in 1928, who was discovered by Howard Pirn. (21) It is possible that Tladi's inclusion in the Academy exhiÂbition of 1930 was at the recommendation of Pirn, a major Johannesburg art collector, who had always encouraged local talent.

In the 1931 and 1932 Academy Exhibitions, the clay sculpture of Hezekiel Ntuli was included in the 'Native Exhibits' category. His entry in 1931 was termed a ' Group of Native Sculptures' and in 1932 he exhibited ' Sculpture model, Solomon King of the Z ulus', ' Sculpture model, Pair Baboons' and ' Sculpture model, Lion '. Ntuli was ' discovered ' in 1929 by Mr. Stanley Williams who arranged for the young Hezekiel to be indentured by arrangement with the Native Affairs Department in Pietermaritzburg. This appears to have left him free to spend his time modelling all day in clay, producing hundreds of animals and people, as well as recording incidents in the artist's life.

In the 1934 and 1935 Academy Exhibitions, Ernest Mancoba exhibited wooden sculptures entitled 'Future Africa' and 'Nobantu (Mother of the People) from life Mancoba had been a student and a staff member at the Diocesan Training College in Pietershurg from 1920 -1929 All of the other black exhibitors at the 1934 and 193 5 exhibitions were students at the Diocesan Training College In all cases they exhibited works designed by the Reverend E. Paterson, including a variety of ecclesiastical objects carved wood. In 1937 and 1938 two of these students. Job Kekana and Richard Makambula, exhibited ecclesiastical carvings of their own design.

Judging from the titles of the works exhibited and a newspaper report of the period, Mancoba, on the other hand, appears to have turned away from ecclesiastical and European sources in exchange for a keener interest in the sculptural tradition of Africa. From as early as 1936 he had begun carving in a far more expressive manner. His interest in the art of Africa was alluded to in this newspaper report.

Recently he came upon a book of primitive African sculpture. He was deeply stirred. It did not seem foreign to him in any way he told me. He was fascinated by the 'pattern within the pattern,' and the way in which the carvings nonetheless remained wholes. (22)

This interest in Africa arose out of recognition of the denial of African culture that had taken place as a result of the European colonisation of Africa and consciousness was possibly heightened during the 1930s with the Italian attack on Ethiopia, which received significant coverage in the black press.

In 1939 Gerard Sekoto was included in the Academ y exhibition, but on this occasion the catalogue did not include a 'native exhibits' category and Sekoto's name appears in the catalogue alongside his fellow white artists However the 1940 exhibition once again reverted to th e practice of separating the black participants under the 'native exhibits' category. The white organizing committee could in part attribute this anomaly to the current perception and expectations of black artists and their work. Apart from the paintings and drawings of Tladi and Sekoto, all the black participants in these early Academy exhibitions were either carving wood [Ernest Mancoba 1934 and 1935] or modelling clay [Hezekiel Ntuli 1931 and 1932 ]. Wood and clay were both materials, which were the expected media of black artists and hence evoked a sense of the traditional, and were therefore treated as a form of 'native art' or craft. Once black artists began using materials associated with the western tradition - oil paints, pastels, watercolors, etc - they achieved a different kind of recognition and acceptance as artists rather than craftsmen within the white art establishment. It is significant that the Johannesburg Art Gallery acquired its first work, an oil painting, by a black South African at this time - a work by Gerard Sekoto.

One of the most isolated but important acquisitions during P. Anton Hendriks directorship was made in 1940 when he purchased Yellow houses: A street scene in Sophiatown, 1940... this was the first work by a black artist acquired by the Johannesburg Art Gallery and for the next 32 years it was the only work. (23)

The art/craft distinction needs to be viewed in conjunction with the changes that were taking place in the exhibition policy of the South African Academy. The crafts section as well as the section of work by students slowly diminished, and by the time the Academy exhibition moved to the Johannesburg Art Gallery in 1943 no craftwork was represented. Hence the creation of a clear distinction between fine art and the other arts did not only apply to the work of black artists. In fact in the early stages of the development of the Johannesburg Art Gallery it was conceived of as an ' Art Gallery and Museum of Industrial Art'; however "the 'industrial' or applied art section did not develop as significantly as anticipated". (24) For a considerable period the Gallery was developed as an exclusive venue for fine art.

Sekoto Gerard (b.1913)

Sekoto Gerard (b.1913)

Yellow houses: A street in Sophiatown, 1940

It is important to note that the art of urban black artists was not only produced for white patrons. John Koenakeefe Mohl, a major figure in the history of black South African art, who lived and worked in Sophiatown and Soweto from the 1940s until the 1980s, also sold work to black patrons and believed in the need to educate his own community.

Mohl's early work, dating from the 1940s and 1950s is to be found in numerous private collections in Soweto. Mr and Mrs J. Skosana, who were coal merchants in Sophiatown, bought works from Mohl when he was working from the 'White Studio ' (where, Mrs Skosana recalls, Mohl was teaching pianoforte, painting, sculpture and flower arrangÂing). Mrs Mable Cooke, who was residing in Western Township in the 1940s, still has an oil painting by Mohl of Sophiatown that was given to her by her mother on the occasion of her wedding in 1948. Throughout the 1970s Mohl exhibited his work in the garden of his home in Moroka Township, Soweto, and sold works to white tourists visiting Soweto as well as to the local residents. His high profile in the Soweto community as well as his active participation in the ' Artist's Market Association ' (25), of which he was a founder member, all contributed to his strongly felt need to communicate his ' genius' to all people.

Mohl John Koenakeefe (1903 - 1985)

Mohl John Koenakeefe (1903 - 1985)

Sophiatown: corner Rey and Edward Streets

I wanted the world to realise that black people are human beings and that among them good workers can be found, good artists and in addition to that I wanted to lecture indirectly or directly to my people of the importance of this type of thing, which of course to them is just a thing. You see there is no difference to them, mean the ordinary African, between a photograph and a picture. It shouldn't be terribly expensive and if you say a painting is about one hundred rand they get shocked and say, ' What do you mean? What are you selling? Are you selling ten oxen or ten cows ?' You see now, I wanted to teach them that this thing is of great importance. (26)

Painting, drawing and sculpture, produced for religious and secular purposes and using western media and stylistic references witnessed its earliest developments in the work of Qwabe, Makoanyane, Mohl, Mancoba, Sekoto, Bhengu and Pemba.

A great deal of the early drawings and watercolours by artists from Natal, such as Simon Mnguni and Arthur Butelezi, are done in an illustrative mode, although not intended as illustrations. However a number of black artists, working from as early as the 1930s and 1940s are best known for their illustrations of books, many of which were commissioned in the 1960s and 1970s. Jabulani Ntuli, in association with Laduma Madela produced a number of drawings for the Bantu bibel, (27) Gerard Bhengu produced a hook (with Phyllis Savory Gerard Benghu; Zulu Artist) (28) containÂing illustrations of people in traditional Zulu dress. Throughout his working career, George Pemba has received a number of commissions to illustrate school textbooks and most recently the front cover for Tim Couzens' book, The New African. (29)

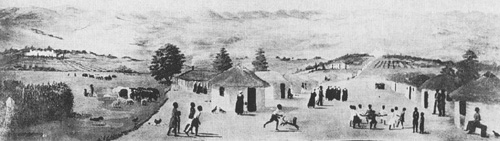

There is also documentation of wall paintings commissioned during the thirties and forties. Unfortunately none of these have survived. The earliest documented figurative mural commissioned by a workers organisation was painted by an anonymous artist at the hall of the Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICU) in Johannesburg, in the 1930s. It portrays the biblical scene of Samson, his chains broken, destroying the temple. (30)

Bhengu Gerard (b.1910)

Bhengu Gerard (b.1910)

Frieze Baptist Methodist Church, Grey St, Durban

Bhengu received at least two commissions to paint friezes; the first was for the Department of Native Affairs in their building at the Empire Exhibition of 1936 (Johannesburg) (31); and the second in the 'Native Troops Recreation Room', in Grey Street, Durban. Judging from a contemporary newspaper report the paintings seemed to have had a dramatic impact:

"One native who suffered from stuttering came into this room a few days ago," said Sergt. -Major Hulley. "He was so struck with the message of Bhengu's paintings that he was cured of his stuttering on the spot. "( 32)

It is important to note that many of the generation of artists discussed thus far, continue to produce art up to the present day. Only a very small part of their creative lives has been represented on this exhibition. Furthermore, they lived and worked in different parts of the country, including Natal, the Transvaal and Basutoland (Lesotho), and although some of their art may have ultimately found its way to the Academy exhibitions, galleries and curio-shops, the context within which they lived and worked require further research. Apart from Sekoto and Mancoba who left South Africa at early stages in their careers, all the artists from this period lived and worked in both a rural and an urban context. The manner in which they reflected this duality was largely determined by the extent of their education and the influences of the various forms of patronage.

The many market forces, including the curio industry, galleries and museums, the church, educational and political bodies, which began to promote art amongst black people in the 1930s, still exist today.

This is also true of the ideas and influences informing the art of the 1930s, which continue to find relevance, including African custom, social reality and township life, and American and European art.

Art became a part of the cash economy, a commodity that could be sold, mass-produced and owned by people with sufficient cash to pay for the privilege of owning either mass-produced or unique images that reflected the condiÂtions of black life.

Endnotes

1. T. Couzens, The New African: a study of the life and work of H.I.E. Dhlomo, Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1985, p. 54.

2. Ibid . p. 35.

3. L. Callinicos, Working life 1886- 1940: factories, townships and popular culture on the Rand, Johannesburg:

Ravan Press, 1987, p. 44.

4. C.G. Damant, Samuel Makoanyane, and Morija: Morija Sesuto Book Depot, 1951, pp. 1 - 2.

5. H.V. Meyerowitz, A report on the possibilities of the development of t t illage crafts in Basutoland, Basutoland:Mori j a Printing Works, 1936. Similar investigations were undertaken elsewhere at a later date. The poor state of craft production in Basutoland (Lesotho) was investigated by H.V. Meyerowitz in 1936.

6. R.H. Reyher, "Natives who are artists in wood carvÂing: the work of the Qwabe brothers", newspaper cutting, 17 April 1937.

7. Ibid.

8. L. Lipshitz, "Sekoto", The African Drum, June 1951, pp. 20-21.

9. E. Berman, Art and artists of South Africa, Cape Town: Balkema, 1983, p. 12.

10. "Zulu life in 500 sq. ft. pictures", The Daily News , 16 December 1937.

11. Damant, Samuel Makoanyane, p. 7.

12. Couzens, The New African, p. 254.

13. Ibid . p. 50.

14 "An artist in clay: native commission surprised:

Model of lion for SA Museum", The Natal Mercury, 13 OctoÂber 1930.

15. "Art among the bantu : May Esther Bedford competition", The Natal Mercury , 10 December 1937.

16. Unpublished correspondence between Barbara Lindop and Gerard Sekoto.

1 ' George Pemba, interview with Steven Sack, Port Elizabeth, April 1988.

18. P. Savory, Gerard Benghu: Zulu artist . Cape Town: Howard Timmins, 1965, p. 10.

19. The state of art in South Africa, conference proÂceedings, University of Cape Town, July 1979, p. 90.

20. The South African Academy was established in 1920 under the auspices of the Transvaal Institute of SA ArchiÂtects and in cooperation with the Transvaal Art Society from 1939. Exhibitions were held in the Selbourne Hal l from 1920 to 1941, in the Duncan Hall in 1942 and 1943, and at the Johannesburg Art Gallery between 1944 and 1950.

21. Couzens, The New African, p. 249.

22. "Primitive art of Africa: Bantu sculptor's studies", The Natal Ad v ertiser, 9 June 1936.

23. J. Carman, "Acquisition policy of the Johannesburg Art Gallery with regard to the South African collection, 1909 - 1987 " , SA J ournal of Cultural and Art History, vol. 2, no. 3, 1988, p. 207.

24. Ibid . p. 204.

25. The ' Artists under the Sun ' is an ongoing exhibition organised by the Artist's Market Association, which was established in I960 in order to promote the work of amateur artists.

26. Couzens, The New African, p. 253 .

27. K. Schlosser, Die bantubibel: des blitzzauberers Laduma Madela - Schopfiingsgi'schichte der Zulu , Kiel: Kommissionsverlag Schmidt & Klaunig, 1977.

28. Savory, Gerard Bengbu.

29. Couzens, The New African, cover illustration.

30. Ibid . p. 27.

31. Savory, Gerard Benghu, p. 10.

32. "Zulu painter's vision: mural depicting the nation's rebirth", The Daily News , 2 November 1942.