Advances in agricultural techniques and practices resulted in an increased supply of food and raw materials, changes in industrial organization and new technology resulted in increased production, efficiency and profits, and the increase in commerce, foreign and domestic, were all conditions which promoted the advent of the Industrial Revolution. Many of these conditions were so closely interrelated that increased activity in one spurred an increase in activity in another. Further, this interdependence of conditions creates a problem when one attempts to delineate them for the purpose of analysis in the classroom.

Changes during the Industrial Revolution in Britain

Factories crated during the Industrial Revolution Changes that were brought on by the Industrial Revolution led to advances and technological innovations which caused growth in agricultural and industrial production, economic expansion and changes in living conditions, while at the same time there was a new sense of national identity and civic pride. The most dramatic changes were witnessed in rural areas, where the provincial landscape often became urban and industrialized following advances in agriculture, industry and shipping. During the 18th century, after a long period of enclosures, new farming systems created an agricultural revolution that produced larger quantities of crops to feed the increasing population. New tools, fertilizers and harvesting techniques were introduced, resulting in increased productivity and agricultural prosperity

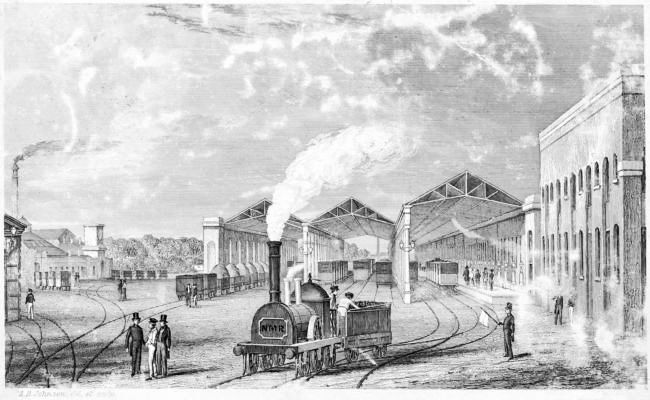

The Creation and use of Railways for transport and to reach other towns Image source

The Creation and use of Railways for transport and to reach other towns Image source

To sustain a growing population, mass production was achieved by replacing water and animal power with steam power, and by the invention of new machinery and technology. The introduction of steam power was a catalyst for the Industrial Revolution. James Watt’s improvements to the steam engine, and his collaboration with Matthew Boulton on the creation of the rotating engine, were crucial for industrial production: machinery could now function much faster, with rotary movements and without human power. Coal became a key factor in the success of industrialization; it was used to produce the steam power on which industry depended. Improvements in mining technology ensured that more coal could be extracted to power the factories and run railway trains and steamships.

Industrialization resulted in an increase in population and the occurrence of urbanization, as a growing number of people moved to urban centres in search of employment. Some individuals became very wealthy, but not everyone shared the same fate since some lived in horrible conditions. Children were sent to work in factories, where they were exploited and ill-treated; women experienced substantial changes in their lifestyle as they took jobs in domestic service and the textile industries, leaving the agricultural workforce and spending less time in the family home. This period also saw the creation of a middle class that enjoyed the benefits of the new prosperity.

Child labour during the Industrial Revolution Image source

Child labour during the Industrial Revolution Image source

Beginning of the Industrial Revolution in South Africa

The discovery of minerals in the late nineteenth century--diamonds in 1867 and gold in 1886- dramatically changed the economic and political structure of southern Africa. South Africa had an extremely valuable resource that attracted foreign capital and large-scale immigration. Discoveries of gold and diamonds in South Africa exceeded those in any other part of the world, and more foreign capital had been invested in South Africa than in the rest of Africa combined. Diamond and, in particular, gold mining industries required an enormous amount of inexpensive labour in order to be profitable. To constrain the ability of African workers to bargain up their wages, and to ensure that they put up with strenuous employment conditions, the British in the 1870s and 1880s conquered the still-independent African states in southern Africa, confiscated the bulk of the land and imposed cash taxation demands. In this way, they ensured that men who had chosen previously to work in the mines on their own terms were now forced to do so on employers' terms. In the new industrial cities, African workers were subjected to a bewildering array of discriminatory laws and practices, all enforced in order to keep workers cheap and pliable. At first the "Rand" became covered by small claims just like at Kimberley, but men like Rhodes, Barnato and Beit who had become wealthy in the diamond mines invested their profits in gold-mining.

Due to the relatively low quality of the ore, it required a lot of digging required to produce acceptable amounts of gold, and that could only be accomplished by using costly heavy machinery. That ruled out most small miners, but other Europeans with access to capital invested in Rand gold mines, and the diamond moguls were never able to achieve the same level of control as they had at Kimberley. By 1889, the South African gold mines were controlled by 124 companies organized into nine "groups" based on their sources of financing.African migrant labour--were first established in the course of South Africa's industrial revolution.

Both mining regions faced the same problem with labour--how to find enough workers and how to keep their cost low. In each case, local governments passed laws at the insistence of the mining companies that limited the right of black Africans to own mining claims or to trade their products. Ultimately, black Africans were relegated to performing manual labour while whites got the skilled jobs or positions as labour foremen. In addition, black workers were forbidden by law from living wherever they wanted, and instead forced to stay in segregated neighbourhoods or mining compounds. The political power of the mining companies became so great that once the Kimberley area was annexed by Cape Colony in 1880, it took only a decade before diamond "baron" Cecil Rhodes was elected prime minister of Cape Colony.

Wealth from the Slave Trade

Mainly, Britain, America, Europe and Africa profited from the slave trade. The trade also created, sustained and relied on a large support network of shipping services, ports, and finance and insurance companies, employing thousands of people. The processing of raw materials that were harvested or extracted by the slaves created new industries where plantation owners profited from the use of free labour. Sir John Hawkins (1532-1595) from Plymouth, was the first Englishman to trade in Africans, making three voyages to Sierra Leone and taking 1,200 inhabitants to Hispaniola and St Domingue (present day Dominican Republic and Haiti) from 1562. The British slave trade started to become a major enterprise in the 17th century, when King James I set up the first monopoly company to trade with Africa in 1618. Britain acquired colonies in America and the Caribbean and demand for slaves to work the tobacco, rice, sugar and other crops on plantations grew. London was the centre of this early trade.In 1698 the monopoly on trade with Africa was abolished, opening up the valuable opportunity to merchants from other ports such as Bristol and Liverpool. Wealth from the direct trade in slaves and from the plantations came back to Britain and was invested in buildings which stand today.

Child Labour during the Industrial Revolution

Child labour, the practice of employing young children in factories and in other industries, was a widespread means of providing mass labour at little expense to employers during the American Industrial Revolution. The employers forced young workers into dangerous labour-intensive jobs that caused significant social, mental, and in some cases, physical damage. Children performed a variety of tasks that were auxiliary to their parents but critical to the family economy. Children who lived on farms worked with the animals or in the fields planting seeds, pulling weeds and picking the ripe crop. Boys looked after the draught animals, cattle and sheep while girls milked the cows and cared for the chickens. Children who worked in homes were apprentices, chimney sweeps, domestic servants, or assistants in the family business. As apprentices, children lived and worked with their master who established a workshop in his home or attached to the back of his cottage. The children received training in the trade instead of wages. Once they became fairly skilled in the trade they became journeymen.

By the time they reached the age of twenty-one, most could start their own business because they had become highly skilled masters. The infamous chimney sweeps, however, had apprenticeships considered especially harmful and exploitative. Boys as young as four would work for a master sweep who would send them up the narrow chimneys of British homes to scrape the soot off the sides. Around age twelve many girls left home to become domestic servants in the homes of artisans, traders, shopkeepers and manufacturers. They received a low wage, and room and board in exchange for doing household chores.

Child labour began to decline as the labour and reform movements grew and labour standards in general began improving, increasing the political power of working people and other social reformers to demand legislation regulating child labour. Union organizing and child labour reform were often intertwined, and common initiatives were conducted by organizations led by working women and middle class consumers, such as state Consumers’ Leagues and Working Women’s Societies. These organizations generated the National Consumers’ League in 1899 and the National Child Labour Committee in 1904, which shared goals of challenging child labour, including through anti-sweatshop campaigns and labelling programs.

Economy before the Industrial Revolution

At the dawn of the eighteenth century, farming was the primary livelihood in England, with at least 75% of the population making its living off the land. The cottage industry was developed to take advantage of the farmers' free time and use it to produce quality textiles for a reasonable price. To begin the process, a cloth merchant from the city needed enough money to travel into the countryside and purchase a load of wool from a sheep farm. He would then distribute the raw materials among several farming households to be made into cloth. The preparation of the wool was a task in which the whole family took part. Women and girls first washed the wool to remove the dirt and natural oils and then dyed it as desired. They also carded the wool, which meant combing it between two pads of nails until the fibres were all pointed in the same direction. Next, the wool was spun into thread using a spinning wheel and wound onto a bobbin. The actual weaving of the thread into cloth was done using a loom operated by hand and foot; it was physically demanding work, and was therefore the man's job. The merchant would return at regular intervals over the season to pick up the finished cloth, which he then brought back to the city to sell or export and to drop of a new load of wool to be processed.

The cottage industry helped to prepare the country for the Industrial Revolution by boosting the English economy through the increase of trade that occurred as the country became well-known overseas for its high-quality and low-cost exports. Previously, tradesmen had done all the manufacturing themselves, so the idea of subcontracting was new and appealing. The cottage industry was also a good source of auxiliary funds for the rural people. However, many farming families came to depend on the enterprise; thus, when industrialization and the Agricultural Revolution reduced the need for farm workers, many were forced to leave their homes and move to the city.

Southern Africa by 1860’s

Brought to the British colony of Natal in1860 as indentured labourers, coolies, on five-year contracts, Indians came to work mainly on sugar plantations where they lived under very harsh and cruel conditions. After five years, they were given the options of renewing their contracts, returning to India or becoming independent workers. To induce the coolies into second terms, the colonial government of Natal promised grants of land on expiry of contracts. But the colony did not honour this agreement and only about fifty people received plots. Nevertheless, many opted for freedom and became small holders, market gardeners, fishermen, domestic servants, waiters or coal miners. Some left the colony. By the 1870's, free Indians were exploring opportunities in the Cape Colony, the Orange Free State and the South African Republic (Transvaal). Those who sought to make their fortunes in the diamond and gold fields were not allowed digging rights and became traders, hawkers and workers.

The first group of Indians arrived in the British colony of Natal in 1860. About 150 indentured labourers arrived at Port Natal on board the ship Truro. When the sugar industry was established in Natal the local Zulu labourers were recruited to work on the sugar plantations. However, the Natal colonial authorities were not initially aware that Zulu males regarded agricultural work as a female activity. Traditionally, the Zulu males were involved in grazing cattle and defending the tribe against foreign attack. The high labour turnover forced the colonial authorities to seek Indian labour that was already successfully employed in other British colonies. The indentured labourers were given a monthly stipend of two British pounds. They were also given provisions and their health needs were catered for. Their earnings as indentured labourers were considerably higher than they could earn in India. Therefore, future shipments of indentured labourers were highly successful. At the end of the initial three year contract the indentured labourers were given a free passage back to India or given agricultural land equivalent to the value of a passage back to India. Owning their own land was an unlikely event in their homeland of India and it is understandable that the majority preferred to remain in South Africa.

Indentured Labourers working at a sugar estate in South Africa. Image source

Indentured Labourers working at a sugar estate in South Africa. Image source

The working conditions of the indentured labourers were harsh. The plantation owners demanded long hours of work in the oppressive humid climate of Natal. Harsh punishment was meted out on labourers who could not keep up with the heavy workload. Their problems were compounded by the fact that they were living in a foreign land with a foreign culture and they also had to contend with many foreign languages. Not everyone could cope with the severe demands. But those who did became land-owning free Indians, considered to be wealthy by the standards of their former homeland. In 1869 a new wave of immigration occurred, of traders from the West Coast, mainly Gujerat. They were called "passenger" Indians as distinct from indentured Indians. The new immigrants, mainly Moslems, were attracted by the rich potentialities for trade that Natal offered. The Gujerati speaking traders were laterjoined by some Urdu speaking Moslems from the United Province and a few Marathi speaking Kokince Moslems.

Diamond Mining in Kimberley from 1867 onwards

Diamonds were formed billions of years ago and are extremely rare because so few are able to survive the difficult journey from the pits of the earth to reach the earth’s surface. From the diamonds that are being mined today, only about 50 percent are thought to be high enough quality to be sold on the diamond market. Many skilled experts will handle a diamond before it makes it to the one that is coveting such a precious stone. The story of diamonds in South Africa begins between December 1866 and February 1867 when 15-year-old Erasmus Jacobs found a transparent rock on his father’s farm, on the south bank of the Orange River. Suddenly, both the Boers and the British were interested in the sovereignty over the area. The area soon attracted a large number of white fortune hunters. Over the next few years, South Africa yielded more diamonds than India had in over 2,000 years.

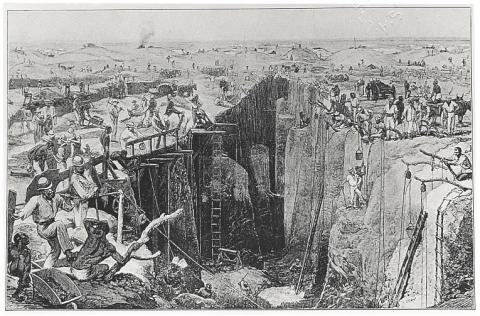

Diamond Mining in South Africa Image source

Diamond Mining in South Africa Image source

In the 1870′s and 1880′s Kimberley, encompassing the mines that produced 95% of the world’s diamonds, was home to great wealth and fierce rivalries, most notably that between Cecil John Rhodes and Barney Barnato.In 1848 the British annexed the entire area between the Orange and Vaal Rivers, which included the Griqualand area, and called it the Orange River Sovereignty with a Magistrate at Bloemfontein who flew the Union Jack. Due to the high costs and low returns the British were to withdraw from the area thanks to the Bloemfontein Convention. It did not help the British that they were about to embark on the Crimean War, so they were looking to consolidate imperial adventures for the time being. In 1854 the Orange Free State was established and the Transvaal would slowly form by 1860. This also meant that Griqualand West was technically independent but it would have to fight off incursions from Boers or any other interested groups. Official British interest in Griqualand was purely opportunistic. In the early 1870s rich diamond mines were discovered. As Griqualand West bordered Transvaal and the Cape Colony, both colonies would claim an interest. The Boers and the British were antagonistic and hostile to each other; each colony did not wish the other to take control of such a rich resource.

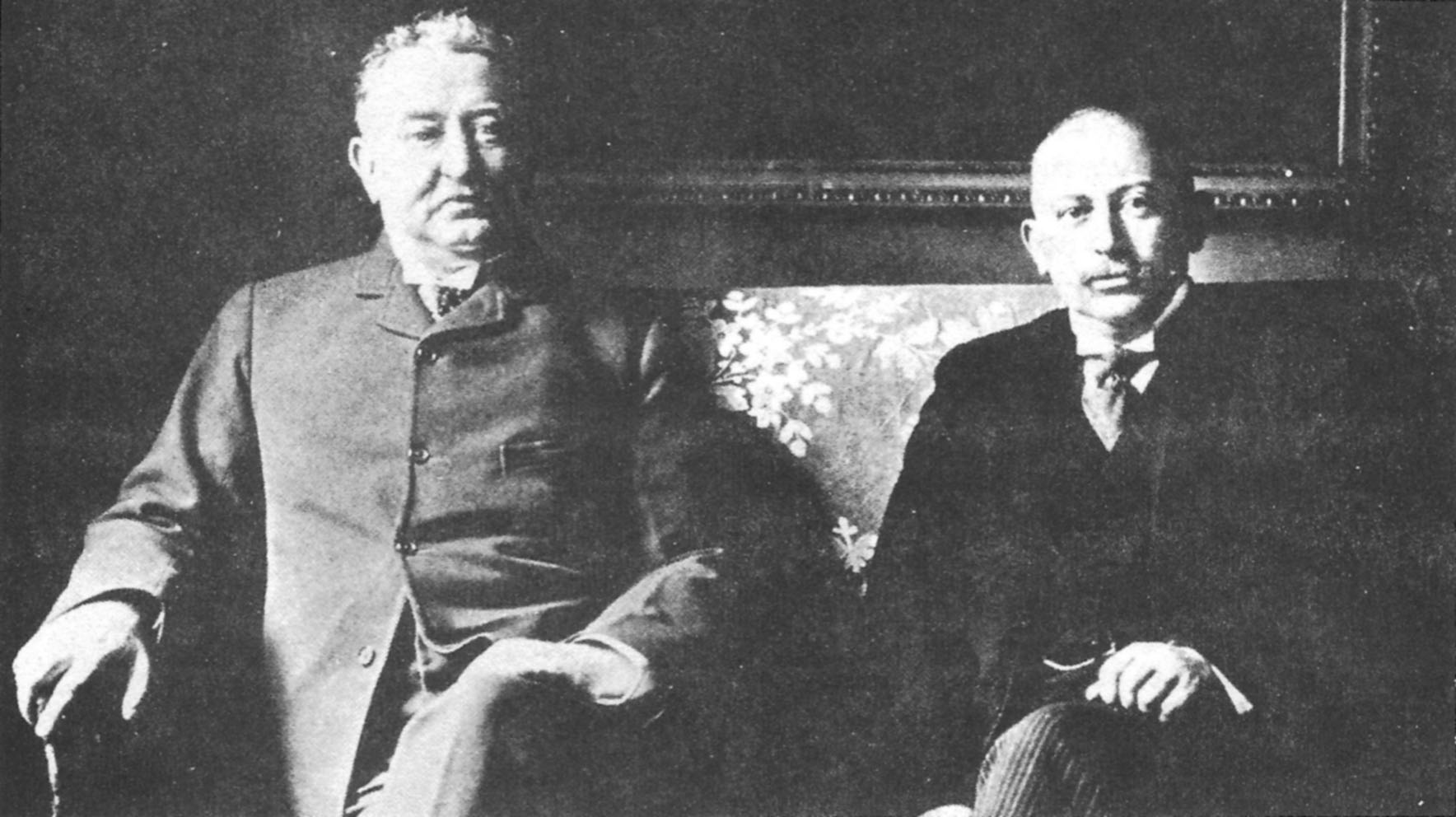

Cecil Rhodes (left) and Alfred Beit Image source

Cecil Rhodes (left) and Alfred Beit Image source

Rhodes, sensing he had ventured into an untapped market, bought up diamond fields, including one owned by two brothers named "de Beer." In 1880, he bought the claims of fellow entrepreneur and rival Barney Barnato to create the De Beers Mining Company. The tendency in diamond mining is to combine with smaller groups to form larger ones. Individuals needing common infrastructure form diggers committees and small claim holders wanting more land merge into large claimholders. Thus, it only took a few years for De Beers to become the owner of virtually all South African diamond Mines.