Related Collections from the Archive

Related content

To explore the patterns of collective memory in South Africa after nearly three decades of democracy, we set out to establish how much of the country’s recent history people in the country still remember.

Close to 3,000 people over the age of 15 responded to the annual round of the South African Social Attitudes Survey (2021) by the Human Sciences Research Council. The nationally representative data suggests that there is low public awareness in the country about key historical events. The Marikana massacre – the killing of 34 striking miners by police on 16 August 2012 – is one of them.

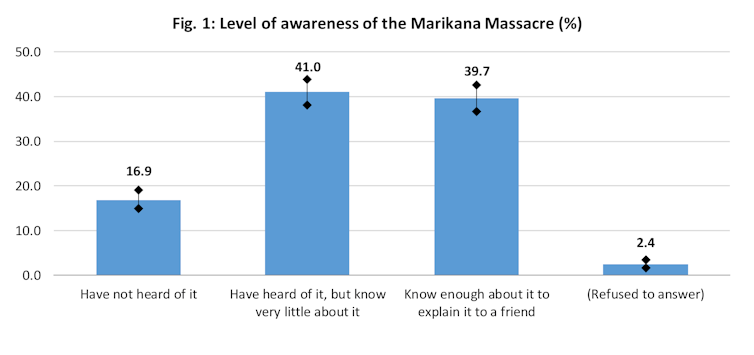

Just over 40% of the survey respondents said they had heard of the massacre but knew very little about it, while 17% said that they were unaware of it. Only 40% reported knowing enough about Marikana to be able to explain it to a friend.

The findings seem to suggest that public awareness of the tragedy is relatively low among the South African public. This raises uncomfortable questions about collective memory in the country, implying a weak acknowledgement and appreciation of important turning points in its modern national history.

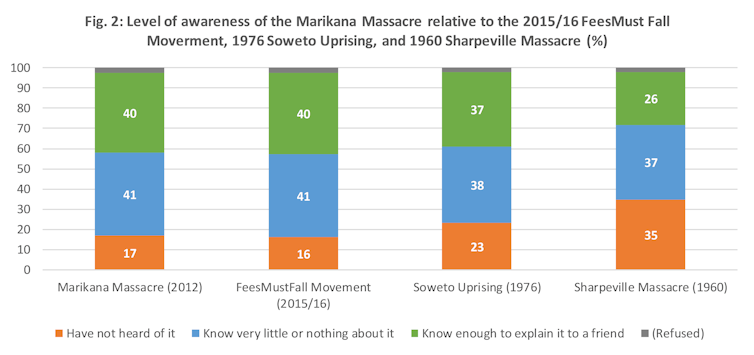

To put the finding in perspective, we compared the responses to the Marikana massacre with other big historical events in the country. These included the #FeesMustFall Movement (2015/16), the 1976 Soweto Uprising, and the Sharpeville massacre (1960).

The results show that awareness of the Marikana massacre was very similar to knowledge about the #FeesMustFall Movement, with 16% having heard of it, 41% displaying limited knowledge, and 40% no awareness (Fig 2).

Familiarity with the 1976 Soweto youth uprising against apartheid education was marginally lower. Awareness of the 1960 Sharpeville massacre, in which 69 peaceful protesters against restrictions on the movement of black people were shot dead, was even lower. The share of respondents who were confident they would be able to describe the historical events to someone else ranged between 26% and 40%.

These findings suggest that awareness is likely to be event-specific. And that it’s influenced by how recently events have happened. But overall the level of knowledge about historical events remains generally quite shallow.

As the philosopher George Santayana once said

those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

Skewed memory

Women were slightly less knowledgeable about the Marikana massacre than men. A high percentage of young people – especially 16 to 19-year olds – as well as those over the age of 65 knew very little. The group that knew the most were aged between 35 and 49.

Less educated and rural adults displayed significantly lower awareness of the Sharpeville massacre. The influence of education is especially pronounced in shaping awareness. Access to information also has a bearing. People with a television at home or internet access displayed higher knowledge levels than those without.

Looking across all these attributes, more than a fifth of youth (16-24 years) and students, those with less than a high school level education, rural residents, and those living in North West, Northern Cape, Free State and Eastern Cape provinces reported not having heard of the Marikana massacre.

The most surprising finding was the relatively low awareness among those in North West province, where the massacre happened. This raises the question of whether this historic event is not adequately represented in the media platforms accessible to this community.

A desire to remember?

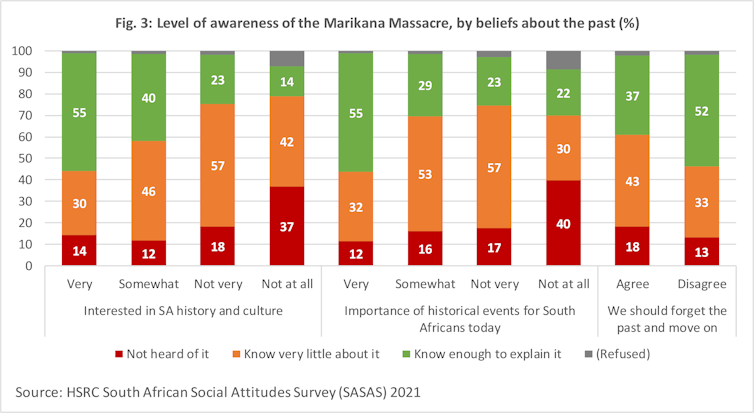

Apart from social and demographic characteristics, the survey also found that individual beliefs about the past and its relevance for the present had a strong influence on awareness of the Marikana massacre (Figure 3).

Firstly, the extent to which people expressed interest in “the history and cultures of South Africa” was found to be a significant factor. Those who were very interested in local history and culture were nearly four times more likely to have high awareness of the massacre than those not at all interested (55% compared to 14%).

A similar pattern was found based on the degree to which South Africans recognised the importance of the past for the present. Those who believed that historical events were very important were two-and-a-half times more likely to confidently explain the events of Marikana, relative to those who did not (55% versus 22%).

Finally, adults were less knowledgeable of the Marikana massacre (37% could explain the event) if they held the view that:

we should forget the past, move on and stop talking about apartheid.

Those challenging this viewpoint displayed a distinctly higher level of awareness (52%).

Given the importance of such beliefs, it is encouraging that many South Africans recognise the importance of the past for the present. Overall, 71% were interested in South African history and culture (38% very, 33% somewhat), while 78% said that historical events such as the Marikana massacre were very or somewhat important today (47% very, 32% somewhat).

More ambiguously, 45% agreed that South Africans should forget the past and move on, while 31% disagreed and 24% were neutral or uncertain.

Commemoration, accountability and justice

The tenth anniversary of the Marikana massacre raises many lingering and uncomfortable questions. These include issues of accountability and culpability, the nature of corporate power and state violence in democratic South Africa, and ultimately of social justice, restitution and healing.

A failure to remember and address the issue of reparations will, as William Gumede, Associate Professor at the Wits School of Governance, has argued, pose the societal risk of “many more Marikanas”.

As former public protector Thuli Madonsela stated in a 2020 Marikana memorial lecture,

Marikana happened because we forgot to remember. We forgot to remember our ugly, unjust past and the legacy it left us … We forgot to heal and we focused on renewal. A renewal without a foundation can’t work.

Samela Mtyingizane, a doctoral researcher at the Human Sciences Research Council, contributed to the research and writing of this article.