Based on the 2012 Grade 10 NSC Exemplar Paper:

Source A:

Source: Author Unknown, “1913 Land Act”, Tshintsha Amakhaya, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 26 October 2020),Image Source

Source: Author Unknown, “1913 Land Act”, Tshintsha Amakhaya, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 26 October 2020),Image Source

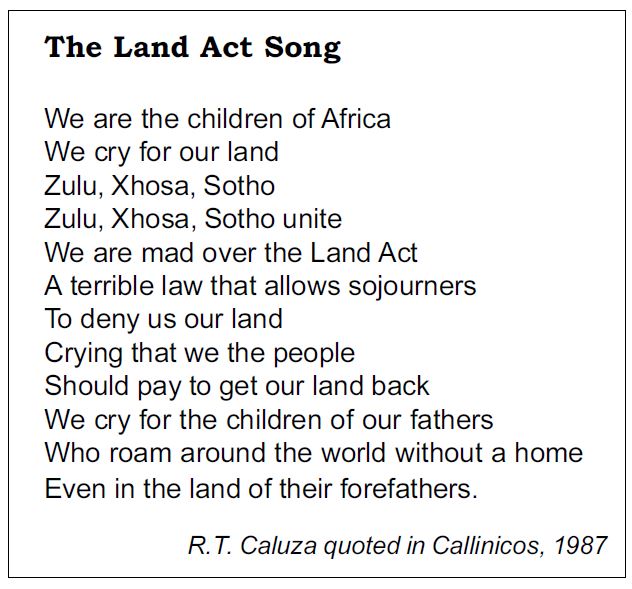

1. How does Source A depict Africans response to the implementation of the 1913 Natives Land Act? (2 x 3 marks)

Source A shows how Africans, whether they were Zulu, Xhosa or Sotho, united to fight against the injustice of the 1913 Natives Land Act. This source, which is a protest song, illustrates Africans anger towards the new law, as they sing: “We are mad over the Land Act.” The song also explains their anger, since they sing that Natives have been deprived of their land by people who are temporary residents in the country. This is seen when they sing: “A terrible law that allows sojourners to deny us our land.” Then the song continues to portray the heartbreak of Africans after the implementation of the law, since they “cry for the children of our fathers, who roam around the world without a home.” Ultimately, this song shows the immediate impact of the law, by singing about the dispossession of land that has changed Africans who lived in their homeland into roamers who were deprived of their human right to own land.

2. Can this source be considered useful? (2 x 2 marks)

Yes, this source can be considered useful, because even though the song was only published in 1987, it still portrays the impact of the Natives Land Act on Africans. The song reminds Africans of their struggle to own land in South Africa and the injustices of the Natives Land Act. It portrays the heartbreak, anger and unification of Africans against the Natives Land Act.

3. Why do you think the song starts with the declaration: “We are the children of Africa?” (1 x 1 mark)

The songwriter starts with the line: “We are the children of Africa”, since it stresses that it is Africans – the children of Africa – who are deprived of their own land by those who are not the children of Africa. This line protests the injustice of the Natives Land Act by affirming that Africans had lost their land by those who are merely “sojourners”, which idea is reinforced throughout the rest of the song.

Source B:

Author Unknown, “1913 Land Act”, Tshintsha Amakhaya, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 26 October 2020), Image Source

Author Unknown, “1913 Land Act”, Tshintsha Amakhaya, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 26 October 2020), Image Source

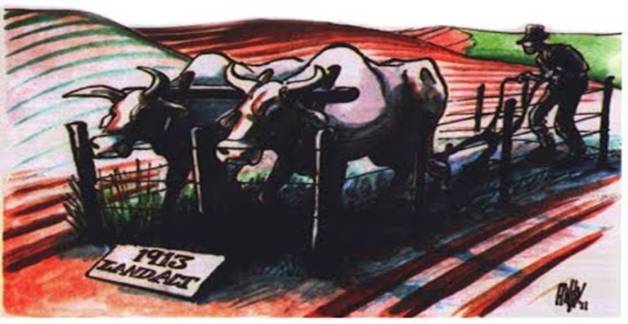

4. Analyze the cartoon above and explain message of this visual source. (2 x 3 marks)

Source B is a cartoon of an African farmer, who owns two cows and a small patch of land, which is surrounded by a fence with the title “1913 Land Act”. It is evidently clear that there is a lot of free land surrounding the African farmer, but it is not available to him. Rather than the fence keeping others out and protecting his land, this fence prohibits the farmer and the cows from expanding their agricultural production and land ownership. The cows, who hardly have enough room to move, and the thin and poor farmer shows the economic impact the Natives Land Act had on African farmers. They could not compete in the economic sector because Africans were impoverished by the 1913 Natives Land Act since they could not become independent farmers. Ultimately, this cartoon portrays how little land (7%) Africans were entitled to and how much land was available to white South Africans (93%).

Source C:

Author Unknown, “1913 Land Act”, Tshintsha Amakhaya, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 26 October 2020), Image Source

Author Unknown, “1913 Land Act”, Tshintsha Amakhaya, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 26 October 2020), Image Source

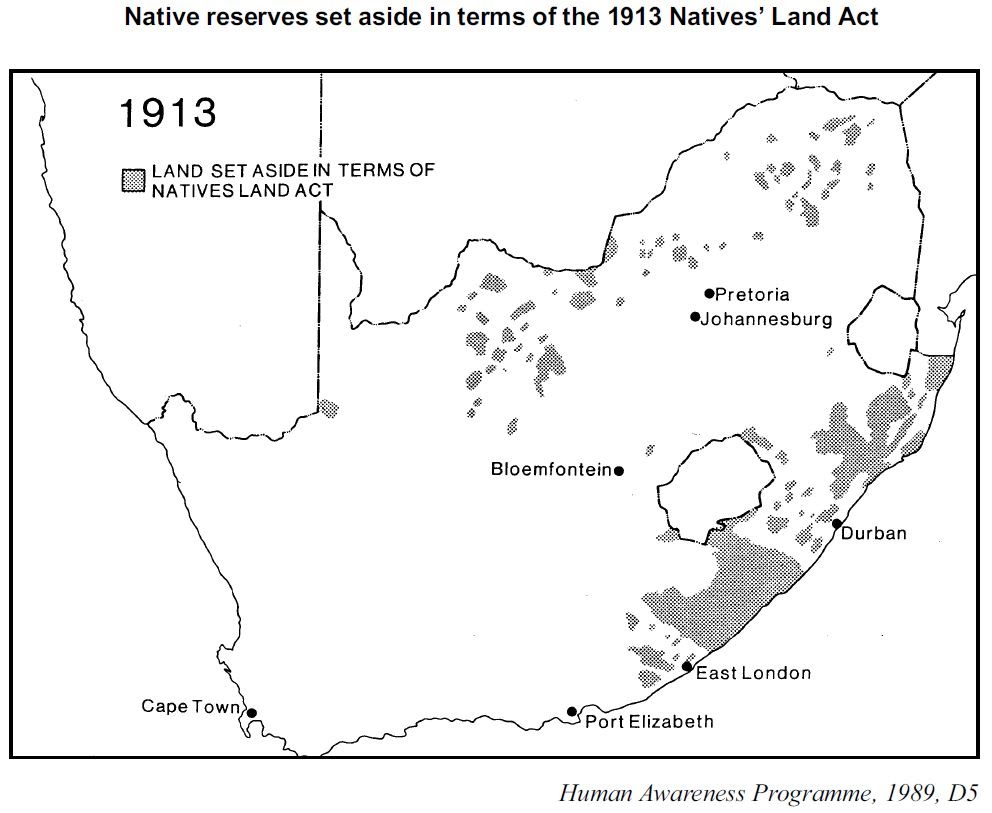

5. The map above illustrates how much land was owned by Africans in comparison with white settlers. Using your own knowledge and the source explain the economic impact of the 1913 Natives Land Act. (2 x 3 marks)

According to the 1913 Natives Land Act, Africans were only allowed to own 7% of the land in South Africa, while the remaining 93% belonged to white settlers. This had a huge economic impact on Africans, since they were no longer able to compete in the market as independent farmers.[1] Africans were also forced into impoverished and overpopulated reserves where the soil was too infertile for proper agricultural production.[2] According to this law, previous practices, such as aharecropping was also declared illegal. Sharecropping referred to when African and white farmers could sow and plant on the same grounds and take a share of the profit.[3] This further impoverished Africans. Ultimately, the Natives Land Act led to a high poverty rate amongst Africans.

Source D:

Author Unknown, “1913 Land Act”, Tshintsha Amakhaya, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 26 October 2020), Image Source

Author Unknown, “1913 Land Act”, Tshintsha Amakhaya, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 26 October 2020), Image Source

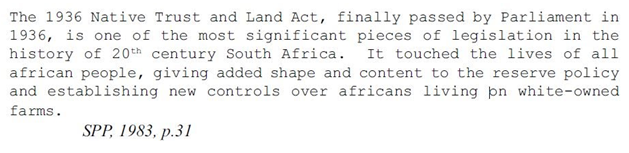

6. In 1936 the Natives and Land Trust Act was introduced. How did this law differ from the 1913 Natives Land Act? (2x2 marks)

In 1936 the Natives and Land Trust Act replaced the 1913 Natives Land Act, which minimally extended the amount of land Africans could own from 7% to 13%.[4] This law, however, continued to impoverish Africans for the economic development of white settlers. According to the 1936 Natives and Land Trust Act Africans were still forbidden to own land outside of the stipulated reserves and could not hire fertile ground from areas allocated to white settlers. [5]

Tips & Notes:

- Check out our Source Analysis and Source Based Questions packs for more tips.

- Remember, these are just examples. You still need to use the work provided by your teacher or learned in class.

- It is important to check in with your teacher and make sure this meets his/her requirements.

This article was originally produced for the SAHO classroom by

Ilse Brookes, Amber Fox-Martin & Simone van der Colff

[1] Author Unknown, “The Natives Land Act of 1913”, South African History Online, (Uploaded: 27 August 2019), (Accessed: 13 September 2020), Available at: https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/natives-land-act-1913

[2] Mtshiselwa, N., & Modise, L. “The Natives Land Act of 1913 engineered the poverty of Black South Africans: a historico-ecclesiastical perspective”, Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae, (Vol. 39), (2013).

[3] Ibid.

[4] Author Unknown, “1936. Native Trust and Land Act No. 18”, O’Malley: The Heart of Hope, (Uploaded: Unknown), (Accessed: 20 September 2020), Available at: https://omalley.nelsonmandela.org/omalley/index.php/site/q/03lv01538/04lv01646/05lv01784.htm

[5] Ibid.