Shirish was born one of eight siblings on 1 March 1938 at 51 Commercial Rd, Fordsburg. Jasmath Nanabhai, Shirish J. Nanabhai’s father, was from the village of Karadi/Matvad in Gujarat, India. Jasmath immigrated to South Africa after the turn of the last century. In a way, it was inevitable that Shirish would get involved in politics because Jasmath was active during his youth in the Indian National Congress, which had fought against British rule in India.

Upon arrival in South Africa, Jasmath settled in Boksburg and was employed as a “duster boy” by a silk merchant on the East Rand. While his duties at this establishment were merely to ensure that the silk was kept clean and dusted, his business acumen led him to learn the trade and become a buyer for the company. This eventually led to a trip to Japan and, over time, he learnt bookkeeping at the same company.

By the time Shirish was born, the family had moved to a flat in Fordsburg near to the famous “Red Square”– the site on which the Oriental Plaza was later built. This was an open space that served as a venue for public meetings and an important rallying point for the movement.

The Red Square was also the site of Shirish’s first arrest in 1955 at the age of 17. He was arrested by the police for chalking a political symbol on a wall in the square. “I was kept for two hours, given a smack and told to go home,” he said.

While a lenient punishment, this first experience of the state’s response to dissent would make real his father’s refrain that political activism, however noble and just, carried with it real consequences that one should be prepared to bear.

Shirish joined the Transvaal Indian Youth Congress when he was a teenager in the mid-1950s. He remembers a social trip to Cape Town organised by the TIYC in 1955 with Moosa “Mosie” Moolla, Suliman “Solly” Essakjee, Farid Adams, Indres Naidoo, and Peter Joseph. He also remembered with great fondness serving soup with his comrades to delegates to the Congress of the People in 1955. He was elected to the executive of the TIYC in 1956.

In 1957, he spent a year in London, England studying at the College of Aeronautical Engineering and returned a year later. He then immersed himself in political work, distributing leaflets and putting up posters for political campaigns.

When the State of Emergency was declared in 1960 and many comrades were detained, Shirish remembered the invaluable role that the local community played. He was responsible for collecting food from Mrs Bhayat and Mrs Pahad and delivering it to the detainees.

His task was to be short lived as he was also detained a month after the emergency was declared. He comforted himself with the thought that many old friends and comrades who were detained would also be at the prison, but when he got to the Fort, he quickly learnt that the detainees had been transferred to Pretoria. He would spend several months in isolation, confined to a cell where the screams of prisoners being whipped were his only companionship.

During this time, black warders would sometimes slip him a daily newspaper or medical officers would insist that the prison authorities allow him time in the prison courtyard.

Shirish remembered driving Joe Matthews – a leading member of the ANC and SACP at the time – with Suliman “Babla” Saloojee to the Bechuanaland border to help get Joe out of the country in the early 1960s.

Reggie Vandeyar approached Shirish in December 1962 to become a member of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK). He received basic training in explosives and was instructed to scout for potential targets. During this same period, he held a job as a clerk at S Malk, a clothing and general merchandise store in Johannesburg. During lunchtimes, he would engage in political activity or meet on street corners to plan operations with members of his unit.

Just five months after he joined MK, he was arrested with his unit leader Reggie Vandeyar and comrade Indres Naidoo. They were caught in the act of planting and detonating explosives at a railway signal box in Riverlea – the fourth in a string of targets. The fourth member of their unit, who had supplied explosives and arms, Gammat Jardine, was a police informer and had betrayed them.

They appeared in court within forty-eight hours and were advised to plead guilty by their legal representative, Dr George Lowen QC. They were each sentenced to ten years in prison. These were the first three members of Indian origin to be arrested for MK activities in the Transvaal.

They were first moved to Leeuwkop Prison on the outskirts of Johannesburg. On arrival, a wing of the prison had been emptied and dedicated to this small group of “dangerous terrorists”. He would later comment with amusement on a massive show of force that the worried prison authorities used to cow the three young men on arrival and the surprise expressed when the “terrorists” turned out to be so human and ordinary. Leeuwkop he remembered most for its cold and cruel conditions. Prisoners were never allowed to wear shoes, even when working in the quarry and were made to run around a courtyard to dry off after brief, cold showers. Here they would later meet up with Joe Gqabi and other political prisoners, which gave them a sense of solidarity and comradeship.

In December 1963, Shirish and seventy other prisoners were transferred by truck to Robben Island. This 1600km drive crammed in the back of a truck was a famously extreme experience but Shirish, with his ever twinkling eye, would speak of the experience of overnighting at the police station in the small town of Richmond. Here, the local police had rushed to accommodate the large numbers of prisoners in their tiny jail, having local people bake fresh bread for them and fashioning extra coffee mugs out of oil cans from a nearby garage.

At Robben Island, the prisoners were housed in communal cells, essentially a hall with blankets and reed mats on the floor. Here they would share cold showers, a single toilet and zero privacy. Being amongst the first political prisoners associated with the Congress movement on the Island, they arrived to find the space dominated by the PAC’s Poqo combatants. They would spend a great deal of time and effort in the early days of confinement negotiating the relationship between these two traditions.

The pointless and brutal manual labour from Leeuwkop intensified here. The warder’s had a slogan they would recite to prisoners working in the limestone quarry: “Klap die groot klip kleiner en die klein klip feiner” (Knock the big stone smaller and the small stone finer).

Due to the large numbers of common law prisoners, Robben Island also had its share of the “Numbers” gangs. Shirish quickly learnt that gangsters were calling the shots in the prison and the warders used these gangs to attack and beat up political prisoners. Slowly, political prisoners, who were in the minority at the time, were able to politicise them and eventually gained their respect. Shirish remembers when one prisoner, known as Whitey, had just been released from solitary confinement, where he was locked up next to Nelson Mandela. He returned to the communal cells proudly proclaiming, “I’m Mandela’s man!” In time, the authorities became aware of the effect that this interaction had on the common law criminals and segregated them into two categories, disallowing interaction. Eventually, the common law prisoners were transferred out and the Island was used exclusively to incarcerate political prisoners.

Life on the Island was occupied by efforts to subvert the status quo, not least to gather information. Trips to the quarry were opportunities to try to steal away for a short time to send messages and collect or distribute goods. They spent much of their time thinking up extremely creative ways to communicate with the outside world too. Similarly, the political prisoners were able to use the common law prisoners, who had greater freedom of the Island, to smuggle goods and news into and around the prison. Efforts were even made to plan an escape and a trench was dug for the purposes (though it was abandoned due to the difficulties posed by the ocean itself).

After a long struggle with the authorities, they started sports clubs in the prison. This was something that was particularly important to Shirish’s memories of the place and he served on the prisoners’ football committee from then on. They cleared and prepared an area for a football pitch and tricked the authorities into providing many of the resources needed for the work.

On the Island, inmates made creative use of all and any resources they were able to access. James Chirwa, a comrade from Malawi, made soccer nets from discarded nylon found on the seashore. One of Shirish’s most treasured possessions is a belt made from the same material that comrade Lambert Mbatha had made for him. He was able to smuggle this item off the Island on his release, a contravention of the rule that all personal belongings became state property. Inmates would also make musical instruments out of kelp and Shirish, in particular, would sew pockets onto prison trousers using old cut-up khaki shirts.

Shirish was eventually released in 1973. He was immediately banned and put under house arrest in Fordsburg, compelled to report once a week at the Fordsburg Police Station. He took every opportunity to flout this banning order with great pride, getting local children to warn him when the police were coming to check on him. He would even arrange to meet with comrades under the auspices of visiting a particular Hindu temple and then simply sneaking out. It was during this period that he met and began courting his Rajula, a childhood friend, for whom he would also gladly break his house arrest conditions. They married in 1978 and moved to Lenasia.

After the expiry of his first banning order and house arrest, he was banned for a further two years without house arrest. During this time, he was expected to report regularly to the John Vorster Square police station in the centre of town, near to his place of work.

At the end of 1979, activists Tim Jenkins, Steven Lee and Alex Moumbaris escaped from Pretoria Central Prison in a famous and daring operation. Immediately on release they went their separate ways and Shirish was soon called upon to provide a hiding place for Lee, while arrangements were made to get him out of the country. He stashed him in an unused upstairs room of the shop where he had worked, overlooked, just a few hundred meters away, by John Vorster Square and the security police – Lee escaped the country days later.

A few weeks later, as Shirish would tell the story, he had one of his regularly scheduled check-ins at that same police station, but at this point, he had put the escape out of his mind and “forgotten about it”. While sitting at the table of a senior officer, another walked in to talk about the investigation of the escape – the sudden shock at being reminded how close he was to that event must have shown on his face, he would say, because the policeman immediately stood up and grabbed him – putting him into detention the same day, before arresting Indres’ younger brother Prema.

He was brutally beaten and tortured with electric shocks during this period of detention but had the presence of mind and consciousness to carefully hide the burn marks from his police guards. They allowed him access to the police doctor once his bruises had healed, thinking there was no evidence of his torture. He immediately showed the doctor, and subsequently his lawyers, the marks and they, in turn, used this to have part of the charges against him dropped. This left him with a shortened sentence of one year for his second stint in prison.

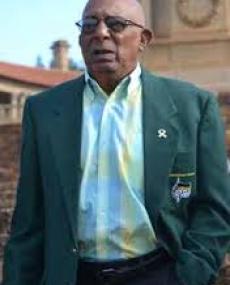

Rajula was not political but became active in the Detainees Parents Support Committee during this period. In recognition of his sacrifices and his immense contribution to the creation of a democratic South Africa, Shirish was awarded the National Order of Mendi in Silver for Bravery 2014.

Shirish and Rajula’s child – their son Kamal – was born in 1980. Rajula tragically passed away in a motorcar accident in 1985. Shirish and Kamal lived together in Lenasia since then.

On Saturday, the 2nd of April 2016, Shirish passed away at the Military Hospital in Pretoria due to respiratory failure.