The esteemed teacher and journalist, Samuel E.K. Mqhayi described Isaac Williams Wauchope:

“Rev Isaac Wauchope was truly handsome in appearance, a broad-faced man, in height a little more than five feet, of light brown complexion, which is to say that he was neither black nor white. He cultivated a luxuriant moustache on his upper lip like that of the slaves. He had an open forehead which signified bravery. He had beautiful teeth with a little gap between the front teeth. He was of average size and as he walked his legs kicked out indicating robust health. He was also bandy-legged. He had a thick mat of hair which suggested he was not about to grow bold.”[2]

Born at the dawn of colonialism, when Europeans were making successful headway into the erosion of Xhosa sovereignty, the destruction of Xhosa society and the theft of the land, Isaac grew up to become a prominent African elite in the Eastern Cape.[3]

Today he is most known for his role as the minister abroad the SS Mendi ship that sank in 1917. However, Isaac’s life prior to his enlistment in the South African Native Labour Contingent (SANLC) was extraordinary considering all his activities, talents and contributions. Isaac wrote extensively on a number of issues that provide a significant lens on the dynamics and issues of his day and reveals to us how the people of his time were dealing with their political predicament. More so, the impact of Isaac’s educational and Christian upbringing with the retention of his Xhosa heritage provides us with an interesting narrative of “a man who straddled two worlds” . [4]

Family Heritage and Upbringing

The Rharhabe people migrated west (the precise date is unclear but it could be estimated to be in the mid-1700s), following the conflict between Rharhabe and his brother Gcaleka, who were the sons of King Phalo. (The people who submitted under a particular leader tended to be called by that leader’s name.) However, their move across the Kei River was opposed by a group of the Khoi people. When the Khoi chief was killed at the battle of the Buffalo Drift, his wife Hoho granted the Rharhabe land for settlement.[5]

As a gesture of goodwill, ten young people were married from each faction. One couple was a Xhosa orphan girl and a Khoi man. The girl was the attendant of Princess Ntsusa, the daughter of Rharhabe.[6]

The couple had two children; a son by the name of Poyana and a daughter by the name of Tse. Tse is the great-grandmother of Isaac. Poyana was killed at a battle between the Rharhabe and the abaThembu in Xuxa in 1782.[7]

Tse married Tsobo and they had three children; Ngo, Tshula and Nqipa.[8]

During this period, Dr J.T. van der Kemp began his missionary work among the amaXhosa and Tse was largely attracted to his preaching. As a result, Tse and her daughter Ngo went with Kemp to Graaff Reinet and Bethelsdorp.[9]

Tse was murdered in 1807 by her employer’s wife, on a farm near Hankey. Ngo, who was also known as Mina, was seventeen years old at the time and gave evidence at the trial in Uitenhage.[10]

Later, Tse married Heka, who was the son of Mandlana. The youngest of their children was Libali, also known as Sabina, who was born in 1828. Libali settled near Uitenhage and in November 1850 she married Dyobha, whose Christian name was William Wauchope.[11]

The name Wauchope derives from the Scottish name, “Werop”.[12]

From the influence of missionaries, it was a trend for some amaXhosa to give their children Christian names.[13]

Dyobha was born in 1821 to Citashe, the son of Silwangangubo who had also passed away at the 1782 battle in Xuxa. Dyobha attended the old Lovedale mission school in Ncerha which was founded by John Ross and John Bennie in 1824.[14]

Dyobha and Libali’s firstborn was a son, whom they named Isaac and his second name Williams was in honour of the missionary, Joseph Williams. Isaac was born in Doorn Hoek near Uitenhage on the 17th of July 1852 during the War of Mlanjeni.[15]

Mlanjeni was a powerful and influential prophet who rallied the amaXhosa to war against the colonialists. This war followed a series of what is known as frontier wars in the Eastern Cape, whereby the amaXhosa attempted to fight off European colonialism and imperialism for the retention of their land and their sovereignty. This particular war saw the amaXhosa suffer severe losses of resources, land and the deaths of their people. Isaac belonged to the Cethe people of the Chizama clan. His royal allegiance was with King Ngqika, but he was known as belonging among the Ndlambe people.[16]

He was born into a 3rd generation of Christian converts and his family had always been near and influenced by missionaries.[17]

Uitenhage was a dispossessed region devoid of Xhosa political authority, thus making him a “black citizen of a white colony”.[18]

Isaac lived among the Rharhabe but was highly influenced by the Mfengu people, a point of great contention for many amaXhosa, as illustrated by Mqhayi’s remarks in his praise poem of Isaac. [See poem attached] These are the rest of Libali and Dyobha’s children, Isaac’s siblings:[19]

● Lydia Mahlamvu

● Mina Manana

● William Wauchope

● Leah Yokwe

● Annie Maqanda

● Peter Wauchope

● Caroline Wauchope

● Harriet Wauchope

●James Wauchope Isaac met his wife, Naniwe, at Lovedale.

Naniwe was the daughter of John Lukalo. She worked as an assistant at a boy’s boarding department from 1874-1879. Isaac and Naniwe got married on the 9th of April 1878 in Uitenhage. The same year, Dyobha died and this was also the period of the last frontier war. Isaac and Naniwe had three daughters; Grisell, Jubilee, Jessie and a son by the name of Isaac or possibly four sons - this fact is unclear. In 1911, Naniwe died. A moving tribute to her can be found among Mqhayi’s works.[20]

On the 21st of January 1913, Isaac married the daughter of Saul Koom ,[21]

who was a Gqunukwhebe.[22]

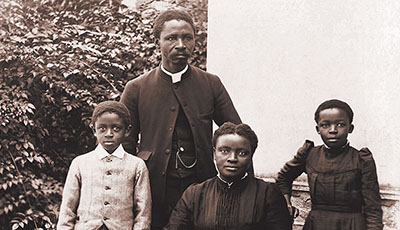

Isaac with his family Image source

Isaac with his family Image source

Education

In 1857, Isaac went to school in Uitenhage and was taught by the likes of Malgas Kunene. He also worked with his sisters in the wool industry cleaning fleeces during his free time.[23]

Between 1860-1865, he went to school in Port Elizabeth (PE). In February 1874, he went to college in Lovedale. He was good at mathematics and won a prize for the best junior student in geometry. He was also an active member of the Literary Society. In March 1875, he obtained his teacher's certificate.[24]

The context in which Isaac received his education can be described by Colin Bundy: “A politicising experience for many students was their encounter with South African history in the form of racially biased textbooks. Several autobiographies attest to the shock of being on the receiving end of the colonizer’s view of the past, especially when this was implacably opposed by versions of the past which the students had heard from their elders.” [25]

Career

Religion

One of the highlighted periods of Isaac’s life in the literature available was his trip to Nyasaland (Malawai). Led by James Stewart, the principle of Lovedale, the travelling party included Lovedale students William Koyi, Shadrach Mngunana and Mapasa Ntintili. They left PE on the 27th of July 1876 to establish a mission.[26]

However, Isaac was sent home in December. It may be due to having fallen ill [27]

or for punching Robert Laws, another member of the missionary party.[28]

There is not enough information to make a substantial deduction as to why he may have punched this individual. Of the trip, Isaac wrote: “This town is situated ten miles up the river. It is inhabited by Portuguese merchants, some Arabs, and thousands of natives. Most of the natives are slaves, but some are free. Some slaves have a better living than the free ones. We can’t carry on any conversation with them since the language they speak is different from ours… I like them very much for they are very industrious, hence they are used in every kind of work. There are boatmen, masons, tailors, and shoemakers among them. Another thing about them is, that they are very civil, that is they know how to conduct themselves before their betters.” [29]

In 1888, Isaac left PE to go to Lovedale as a theology student. On the 6th of March 1892, he was ordained as Pastor of the Congregational Native Church of Fort Beaufort and Blinkwater in the presence of James Read of Philipton, Henry Kayser of Alice, Pambani Mzimba and T. Durant Philip of Lovedale.[30]

The following is an excerpt regarding Isaac’s ordination from The Christian Express:

“Mr Wauchope is a man of superior ability, and has experience of life and men. He can preach, if need be, in four languages, Kaffir, Dutch, English, and Sesuto, and the Fort Beaufort church ought to be prosperous under his ministry.”[31]

Isaac served as a pastor for fifteen years. However, reconciling his Christian and Xhosa identity was an issue of contention as revealed by his writings. At first he supported missionary opposition to Xhosa customs, but eventually, he found some degree of balance in the maintenance of two identities.[32]

This excerpt from Imvo in 1903 by Isaac best illustrates his thinking: “1. First, native customs that do not conflict with the light that comes from the Word of God should not be eradicated for the sole reason that they are not found among the English. Instead, they should be smoothened, all the coarseness and lumps should be removed and they should be moulded to suit our present state of cultural development. 2. Second, evidently bad customs that are not in harmony with the light and conflict with the Christian way of life should be displaced by others derived from this new light – they should not be simply rejected without something to replace them.” [33]

Isaac, despite the beliefs he expressed in his writings, was also a proud Xhosa man and held appreciation for his culture. Blyden notes that part of the process of European colonization of the subjugated mind is that people tend to inadvertently hold up, counter and accept the standards of the oppressor against that of the expression of their own institutions.[34]

Isaac was aware of the physical role of European colonization against the amaXhosa, but it is not clear from his writing whether he was conscious of the role of missionary ideology, education and activities in the process of subjugating his people. In 1885, Isaac wrote an article The Christianization of the Natives and the following is an excerpt:

“Possibly I am somewhat biased because I had the good fortune to be born and brought up in a town mission and to be in contact with Europeans from a child. I thank God for that. I look upon all European Christians as brothers and sisters in the Lord, without necessarily expecting to be invited to their dinners and tea-parties and to be ‘mistered’, and all that sort of thing, as a sign of brotherhood or sisterhood. I look upon all missionaries, of whatever denomination, as friends and benefactors, and as worthy of the esteem of all native Christians.”[35]

Beyond Isaac’s personal religious challenges, one of the big issues of the time, which was also given a lot of thought by Isaac, was the African Independent Churches movement, or also known as Ethiopianism, as a counter to European missionaries. In 1899, Isaac wrote about the matter in The Christian Express in 1899:

“They say, first, that the Gospel of Jesus Christ was not introduced wisely into this land, inasmuch as it came divided into many sects whereby the natives of this land were divided into small sections more or less antagonistic to one another. This to the heathen meant so many different Gospels. They say then some strong Native Church, one partaking of the tenents of most of the stronger denominations should be formed, with which all the existing denominations should amalgamate.” [36]

Furthermore, he went on to disagree with the movement and based his argument on the premises that 1) men spearheading this were more concerned for their own religious ambitions that were curtailed by Europeans, and 2) Africans were not capable of doing missionary work because Europeans had capital, authority, law, experience and influence. Isaac was quite critical about this new movement, writing that not every African wanted to be a part of it.[37]

Politics, Activism and Other

Isaac’s political career had a controversial nature to it. After 1902, Africans began mobilizing and coordinating across regional barriers.[38]

Isaac was an ally of John Tengo Jabavu.[39]

Jabavu produced a newspaper called Imvo Zabantsundu that promoted Mfengu causes. The Mfengu Strategy that was articulated in the newspaper was essentially black support of sympathetic Whites. Relations between the Mfengu who were originally refugees from Shaka’s region were tense.[40]

In the 19th Century, they settled in Cape territory and supported Whites in the frontier wars against the amaXhosa. Some of Isaac’s other political involvements included The Native Education Association in 1880, which started as a teacher’s trade union dealing with voter registration, representation of Blacks on juries and the opposition to pass laws.[41]

Another early political organization that Isaac helped found as a response to the Afrikaner Bond, was the Imbumba Yamanyama (meaning unity in strength).[42]

Isaac acted as secretary for its inaugural meeting in September 1882.[43]

Isaac was a shareholder of the African American Working Men’s Union that was formed to encourage African entrepreneurship.[44]

In 1888, Isaac formed part of a delegation, along with J.T. Jabavu and Elijah Makiwane, that was sent to Cape Town to oppose the pass laws. The bill was successfully withdrawn.[45]

Of note, Isaac turned down invitations to be involved with the South African Native National Congress and remained absent at its inauguration in 1912.[46]

This excerpt from Isaac’s letter in Isigidimi amaXosa in 1882 reveals something of Isaac’s political nature:

| ElokuvumisaZimkile! Mfo wohlanga, Putuma, putuma; Yishiy’ imfakadolo, Putuma ngosiba; Tabat’ ipepa ne ink, Lik’aka lako elo. | Your cattle are plundered, compatriot! After them! After them! Lay down the musket, take up the pen. Seize paper and ink: that’s your shield. |

| Ayemk’ amalungelo, Qubula usiba; Nx’asha, nx’asha, nge inki, Hlala esitulweni Ungangeni kwa Hoho Dubula ngo siba. Tambeka umhlati ke, Bambelel’ ebunzi; Zigqale inyaniso, Umise ngo mx’olo; Bek’izito ungalwi, Umsindo liyilo. | Your rights are plundered! Grab a pen, load, load it in with ink; sit in your chair, don’t head for Hoho: fire with your pen. Press on the page, engage your mind; focus on facts, and speak loud and clear; don’t rush into battle: anger talks with a stutter.[48]

|

Isaac was also involved in the following activities:

● Translation

● Activist work that involved land rights, teachers’ pay, the defence of leaders and the release of Xhosa chiefs[49]

● Interpreter and clerk at the Magistrate Court in PE[50]

● Fundraiser for the Inter-State Native College Scheme which collected funds for an African college to be built and resulted in the establishment of the South African Native College, later called the University of Fort Hare[51]

● Taught in his old Uitenhage school till 1882 (in his teaching career he taught Charlotte Manyene Maxeke )[52]

● PE Debating Society Member[53]

● Coached sport [54]

● Leading member of the Independent Order of True Templars[55]

● Vice-chair of Ibandla le Tiyopiya (Ethiopian Benefit Society) a self-help organization; which aimed at reducing tensions in townships in PE[56]

● Head of the Eastern Grand Temple 1893-1896, 1898, 1907-1908[57]

With the International Order of True Templars Image source

With the International Order of True Templars Image source

Literature

Isaac’s archive of written works cover topics such as religious affairs, history, biographies, politics, folklore, language, poetry, hymns, travelogues, sermons, translations, explanations of proverbs, obituaries, royal praise poetry, education, drunkenness and the merits of Xhosa custom. He wrote in the form of letters, announcements, articles, reports and lectures in contributions to newspapers such as Isigidimi samaXosa, Imvo zabantsundu and The Christian Express. He also wrote a forty-seven page booklet; The Natives and Their Missionaries, published by Lovedale Press in 1908.[58]

Isaac’s Izintsonkoto zamaqalo is the earliest philosophical writing in isiXhosa.[59]

During his time in Tokai Convict Prison, Isaac wrote six poems; the earliest isiXhosa prison literature. Isaac was an advocate of studying isiXhosa composition and grammar. He saw the value of the English language as a channel of access to more literature but also recognized the need for translation of what was learnt back to African languages. He believed in the teaching of African languages in schools as important for the development of African literature.[61]

To be accurate, Isaac contributed over one hundred and sixty writing items in English and isiXhosa.[62]

Isaac’s writing could be considered quite controversial at times and he was not always factually correct. His sources included written text and witness accounts.[63]

The names Isaac wrote under, varied from his initials, pseudonyms and family praise names:[64]

● Isaac Wauchope

● I.W.W.

● William Wauchope

● I.W. Wauchope

● Wauchope

● Dyobha

● Dyoba wo Daka

● Ngingi Dyobudaka

● Ngingi Dyoba Wodaka

● Ngingi or Nginginya

● Bozwa Buhele

● I.W. Citashe

● I.W.W. Citashe

Silwangangubo Isaac left behind a very important intellectual legacy, because he was “in the vanguard of those authors who pioneered the publication of original Xhosa poetry in newspapers towards the end of the nineteenth century”.[65]

Unfortunately, much of this work’s value has limited access because of the unfamiliarity with the Xhosa language that Isaac and scholars such as him used, as it differs largely to the isiXhosa spoken today. Mqhayi and Isaac had an interesting relationship. Mqhayi was a family friend, who provided assistance to Isaac’s mother when she was ill. A talented literate, Mqhayi was wounded by Isaac’s critical review of his first novel USamson in 1908.[66]

Isaac was criticised for his reviews, which were mainly to do with the political offence at Mqhayi’s diversion from the biblical narrative.[5]

Of the matter Mqhayi wrote:

“After it was critically reviewed for three successive weeks in the columns of Imvo by Rev. I.W. Wauchope, who pounded it to his own detriment, it was quickly sold out. I am pleased to say that Rev. I.W.W. later put things right with me about this, and at his death, we were great friends again.”[68]

Though they did not publish books, the following authors, including Isaac and Mqhayi, paved a significant path forward for isiXhosa literature in print and were at the “forefront of the intellectual ferment that drove the modernising movement” [69]

: [70]

● M.K. Mtakati

● William Kobe Ntsikana

● Jonas Ntsiko

● John Muir Vimbe 5.

Prison

In June 1905, Sarah Bobi Tshona died. Isaac managed Bobi Tshona’s estate since his death and Isaac said that Sarah gave him a verbal testament on her deathbed. At a meeting in October 1906, Isaac told the family that Sarah left no written will, but he applied to be her executor.[71]

On the 27th of September 1907, the Circuit Court for the District of Fort Beaufort took case evidence: Elijah Tshona and Others versus Isaac Wauchope and Others. The beneficiaries of Sarah’s will were represented by Isaac and the children excluded from the will, who wanted Isaac’s executorship terminated, were represented by a Grahamstown law firm.

Isaac wrote to the court about Sarah:

“On Feb 05 at the wedding of one of her daughters she handed me her will for safe keeping. She had had the keeping of it since May 04,”[72]

The opposition said that in October 1906 Isaac told them he had had no written will from Sarah and eighteen months later he said there was one. Isaac’s witnesses of the will could not be traced to give evidence and an expert in handwriting determined that all signatures of the will from the two witnesses and Sarah were all in the same hand. Isaac, however, maintained he had no motive for forgery. [73]

In August 1908, a judgement was made. The will was set aside because of suspicion of forgery and Isaac’s witnesses were considered improbable. The court declared that Isaac:

“Stands under a presumption of forgery or its equivalent fraud and misrepresentation by (a) obtaining letters of administration from the Master of the Supreme Court on an instrumental purporting to be the last Will of Eliza Tshona but which was not a valid and legal document, (b) representing the signatories to the alleged Will to be bona-fide subscribers with fraudulent intent to deceive, (c) filing death notice with similar intent.”[74]

Public opinion on the matter was divided, but funds were collected for his defence. Four months later Isaac was arrested in Fort Beaufort in December 1908, having stood accused of forgery in a preliminary hearing. An application of discharge was made by his lawyer, R.W. Rose-Innes on the basis that 1) there was no evidence of intent to commit fraud and Elijah admitted Isaac had to relay verbal instruction from Sarah and 2) Isaac had not benefited from his actions.[75]

Nonetheless, Isaac was found guilty and sentenced for five years of hard labour. In early 1910, he entered Tokai Convict Prison near Cape Town.[76]

Of the reaction of the community, Jonas Ntsiko commented:

“If our East London newspaper speaks for the Xhosa people, we can say this outstanding man did not receive the same sympathy; instead, his community drew a knife and presented it ostentatiously to the prosecutors saying: What’s stopping you from slitting his throat?”[77]

A year later, in 1911, Isaac’s first wife Naniwe passed away. In July 1911, Isaac wrote to Imvo: (Translated to English)

“I cannot say anything now about my removal from society and the scattering of my family. Of all my misfortunes nothing is worse than being left by my wife after 33 years together, living a life of love and mutual support in God’s work. Yet God saw to it that I couldn’t close her eyes! Besides that my grandchild has passed away before his grandmother died. The cost of the case has left me with not even a fowl because it amounted to £400, so I had to sell all the moveable goods I possessed. My wish is that my soul will remain concealed behind the cross of Jesus and attain eternal salvation.” [78]

In March 1897, Isaac and five others had obtained a plot of land in Durban Street in their capacity as trustees of the Congregational Church of Fort Beaufort. In 1911, this church wanted to change the names of the trustees on the title deed and they intended to force Isaac out, but Isaac willingly gave up the plot of land:

“As soon as I am released I shall vacate the premises in Durban Street & hand over to Rev. Mark Wilson the keys and all documents belonging to the Church-or such of them as I shall find still safe in my house. He will kindly convey to the Executive of the Union that I am as jealous as any man could be for the honour of my Church and will do nothing wilfully to add to the disgrace into which it has already been plunged through my grievous fault. Whatever compensation they consider I am entitled to I am confident that it will be given.”[79]

These two excerpts indicate Isaac’s feeling with regards to his predicament. He was released in January 1912, after a successful appeal to the Superintendent of the Tokai Convict Station. He lived in Knapps Hope after his release.[80]

The SANLC and the SS Mendi

In 1916, Isaac enrolled in SANLC as an army chaplain and moved to Cape Town where he awaited his departure and assisted the authorities, because “he had a high reputation and he could obviously help in training the newcomers by explaining white things to them.”[81]

The SS Mendi left Cape Town for England and from Southampton, it crossed the Channel to France in February 1917. On the 21st of February, the SS Darro ship collided with the Mendi. The Mendi then sank resulting in the death of 600 African men who drowned. Isaac was one of them. An excerpt from Imvo in 1917 wrote:

“News reached the family of the late Rev. Isaac W. Wauchope in Fort Beaufort that he was among those who went down with the ship Mendi in England. This news shocked everyone who heard it because this son of Dyobha of the Cethe clan was one of the highly talented black people of our land.”[82]

Albert Grundlingh wrote how legend “describes an elaborate death drill just before the Mendi disappeared beneath the waves and a stirring address by Rev. Isaac Wauchope Dyobha, extolling the virtues of African unity.”[83]

Mqhayi wrote:

“Those who were there say the hero from Ngqika’s land descended from heroes was standing to one side now as the ship was sinking! As a chaplain he had the opportunity to board a boat and save himself, but he didn’t! He was appealing to the leaderless soldiers urging them to stay calm, to die like heroes on their way to war.” [84]

Norman Clothier, in 1941, wrote of the death drill:

“It is not confirmed by any survivor’s or official account, but oral tradition has preserved it and the press has kept it alive. It has stirred the emotions of all who have heard it.” [85]

These are the famous words that make up the legends of Isaac’s final words on the ship:

Be quiet and calm, my countrymen, for what is taking place is exactly what you came to do. You are going to die… but that is what you came to do… Brothers, we are drilling the death drill. I, a Xhosa, say you are my brothers. Swazis, Pondos, Basutos, we die like brothers. We are the sons of Africa. Raise your war cries, brothers, for though they made us leave our assegais in the kraal, our voices are left with our bodies.”[86]

Isaac is listed in the Hollybrook Cemetery in Southampton along with the other fallen SANLC, as “I. Wanchope”.

Natalia laying a wreath at the Cross of Sacrifice Image source

Natalia laying a wreath at the Cross of Sacrifice Image source

The year 2017 marked the centenary of the sinking of the SS Mendi. A ceremony was held to commemorate the historical event, wherein the South African Navy provided a guard of honour and a military band. Speeches were made by the likes of Minister Jeff Radebe and wreaths were laid by some of the descendants of the SS Mendi SANLC men at the wreckage site. Natalia Sifuba, a fifth-generation descendant of Isaac, was among these guests. Her grandfather, Brister Ngingi was Isaac’s grandson.[88]

Natalia recounted:

“Our grandfather told us that when the accident happened, this is when the panic happened but because of the reverend’s bravery, he began to calm the men, to make them brave enough to face death…I’m very honoured to be there on behalf of the family. Both Kuku and George perished in faraway lands, just like my ancestor, we all participated in the struggle. My ancestor’s activism was not in vain, South Africa is actually free.”[89]

Endnotes:

[2]S.E.K. Mqhayi, Abantu Besizwe – Historical and biographical writings, 1902-1944 (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2009), 480 ↵

[3]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xvii. ↵

[4]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xviii. ↵

[5]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xviii. ↵

[6]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xviii. ↵

[7]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xviii. ↵

[8]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xviii. ↵

[9]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xviii. ↵

[10]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xix. ↵

[11]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xix. ↵

[12]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 367 ↵

[13]S.E.K. Mqhayi, Abantu Besizwe – Historical and biographical writings, 1902-1944 (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2009), 470. ↵

[14]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xix. ↵

[15]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xix. ↵

[16]S.E.K. Mqhayi, Abantu Besizwe – Historical and biographical writings, 1902-1944 (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2009), 470. ↵

[17]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xiii ↵

[18]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxxiii. ↵

[19]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 145 ↵

[20]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxxii ↵

[21]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxvi ↵

[22]S.E.K. Mqhayi, Abantu Besizwe – Historical and biographical writings, 1902-1944 (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2009), 474. ↵

[23]S.E.K. Mqhayi, Abantu Besizwe – Historical and biographical writings, 1902-1944 (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2009), xix ↵

[24]S.E.K. Mqhayi, Abantu Besizwe – Historical and biographical writings, 1902-1944 (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2009), xix ↵

[25]S.E.K. Mqhayi, Abantu Besizwe – Historical and biographical writings, 1902-1944 (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2009), 77 ↵

[26]S.E.K. Mqhayi, Abantu Besizwe – Historical and biographical writings, 1902-1944 (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2009), xix ↵

[27]S.E.K. Mqhayi, Abantu Besizwe – Historical and biographical writings, 1902-1944 (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2009), 472. ↵

[28]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xx. ↵

[29]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 12. ↵

[30]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxi ↵

[31]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 376 ↵

[32]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 6 ↵

[33]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 325 ↵

[34]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 233 ↵

[35]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 22 ↵

[36]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 23 ↵

[37]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 23 ↵

[38]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxi ↵

[39]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xvii ↵

[40]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxii ↵

[41]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 162 ↵

[42]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 162 ↵

[43]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xx ↵

[44]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xx ↵

[45]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxi ↵

[46]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxi ↵

[47]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 165-6 ↵

[48]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 168-9 ↵

[49]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 161 ↵

[50]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xx ↵

[51]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxii ↵

[52]S.E.K. Mqhayi, Abantu Besizwe – Historical and biographical writings, 1902-1944 (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2009), 472. ↵

[53]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xx. ↵

[54]S.E.K. Mqhayi, Abantu Besizwe – Historical and biographical writings, 1902-1944 (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2009), 474. ↵

[55]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xvii. ↵

[56]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xx ↵

[57]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 163 ↵

[58]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxviii. ↵

[59]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 234 ↵

[60]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xvii. ↵

[61]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 313 ↵

[62]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxviii. ↵

[63]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 78 ↵

[64]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxix ↵

[65]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 330 ↵

[66]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxx ↵

[67]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxxi ↵

[68]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxxii ↵

[69]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxxiii ↵

[70]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxxix ↵

[71]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxiii ↵

[72]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxiii ↵

[73]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxiv ↵

[74]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxiv ↵

[75]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxiv ↵

[76]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxv ↵

[77]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 385 ↵

[78]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxv ↵

[79]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxvi ↵

[80]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxvi ↵

[81]S.E.K. Mqhayi, Abantu Besizwe – Historical and biographical writings, 1902-1944 (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2009), 476. ↵

[82]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), 397. ↵

[83]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxvii ↵

[84]S.E.K. Mqhayi, Abantu Besizwe – Historical and biographical writings, 1902-1944 (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2009), 478. ↵

[85]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxvii ↵

[86]Jeff Opland and Abner Nyamende, Isaac Williams Wauchope – Selected Writings 1874-1916 (Paarl: Van Riebeek Society, 2008), xxvii ↵

[87]Centenary News Editor, “Remembering the SS Mendi - South Africa leads centenary tributes”, Centenary News First World War 1914-1918, 22 February 2017 accessed 24 August 2017, www.centenarynews.com ↵

[88]Kevin Ritchie, “'My ancestor started our family struggle for freedom'”, IOL, 14 February 2017 accessed 24 August 2017, Available [Online]: www.iol.co.za ↵

[88]Kevin Ritchie, “'My ancestor started our family struggle for freedom'”, IOL, 14 February 2017 accessed 24 August 2017, Available [Online]: www.iol.co.za ↵