Abstract: Many South African Jews such as Eli Weinberg were heavily involved in the country’s anti-apartheid movement and faced exile as a result; other Jews refrained from action. In both cases, these individuals were influenced by their religion and their upbringing in Jewish communities experienced in prejudice.

Keywords: Eli Weinberg, Jew, exile, apartheid, anti-Semitism, Communist Party, political activism, religion

Eli Weinberg: Reflections on the Jewish Community and Apartheid

Eli Weinberg was born in 1908 in the port city of Libau, Latvia to a Jewish family. Growing up, he experienced notable events such as World War I and the 1917 October Revolution and became involved with local trade unions. Concerned over his home country’s political situation, Weinberg left Latvia in 1929 and arrived in Cape Town, South Africa on 9 December 1929. Until his exile to Dar es Salaam, Tanzania in 1976, where he died in 1981, Weinberg lived in South Africa, even considering himself South African despite his lack of citizenship. Though he arguably garnered his prominence through his involvement in the Communist Party of South Africa and the country’s anti-apartheid movement, as evidenced through his role in internationally acknowledged trials calling out communists, Weinberg is also remembered as a photographer. Weinberg’s photography career dates back to 1926, when he held a part-time job at his friend’s photography studio. Upon arrival in South Africa, Weinberg furthered his photography career, even winning a silver medal at the 1964 New York World Fair for a 1962 image featuring Basotho women in the Maluti Mountains. In addition to running his own studio and training notable black photographers such as Joe Gqabi, he also shot on assignment for New Age, a weekly publication that supported the African National Congress (ANC).[i] These photographs, which documented South Africa’s shanty towns, the pass laws, pass burnings, bus boycotts, the Treason Trial, and countless demonstrations and protests, illustrated the horrific nature of apartheid and the efforts of those fighting against the system. For Weinberg, his work for New Age “was a source of great pleasure and inspiration to me”;[ii] it allowed him to prove the existence, good intentions, and widespread support of the movement resisting apartheid. Through his decades as a photographer and his personal involvement with South Africa’s trade unions and communist party, Weinberg successfully dedicated his life to furthering the anti-apartheid cause. In many ways, his Jewish identity shaped his commitment to the fight against apartheid; his religious beliefs and upbringing in a family that experienced anti-Semitism and systematic prejudice inspired his actions. Eli Weinberg’s embodiment of his Jewish identity and his story – his early life in Latvia, move to South Africa, involvement in the anti-apartheid movement, position in the country, and exile – mirror that of other Jewish figures in South Africa. However, his characteristics were not entirely ubiquitous amongst members of South Africa’s Jewish community; many acted as bystanders which both contradicts and coincides with the tradition of Jewish discrimination and extermination.

Ever since the destruction of the first Temple in 586 BCE, Jews have undergone constant migration, anti-Semitism, and discrimination. The millennia-long history of “social isolation, curtailment of opportunities, harassment, persistent attack, pogrom, exile – and exclusion from life” has led historian Robert Wistrich to call anti-Semitism the world’s “longest hatred.”[iii] Even in modern times, anti-Semitism has remained rampant, presenting itself in discriminatory policies and inhumane acts such as pogroms and the Holocaust. When Eli Weinberg was growing up in Eastern Europe in the early 20th century, his Jewish community experienced pogroms and other instances of significant bigotry – during World War I, Russian generals blamed Jews for their failures at the hands of the German army, accusing them of espionage and collusion with Germany. This resulted in the deportation of forty thousand Jews in cattle cars. However, Marxist and liberal political parties like the Latvian Democratic Party supported Jews in their struggle to attain equality and fair treatment. As a result of this relationship and the economic hardships faced by a significant number of the region’s Jews, socialism gained traction with members of the Eastern European Jewish community.[iv] Eli Weinberg exemplifies this religious and ethnic connection to socialism; he cites his upbringing in a poor, marginalised Jewish community and a tumultuous political environment as his catalyst for joining a trade union at sixteen years old and for identifying with communism prior to his time in South Africa. His intense involvement with socialist causes in Latvia even resulted in his imprisonment in 1928, when he participated in a strike against potential anti-trade union legislation.

After he left Latvia for South Africa in 1929 because of political turmoil, his devotion to social action and victimised communities continued. He joined the Communist Party of South Africa in 1932 (when it was still legal) and participated in trade union activity in Johannesburg, Cape Town, and Port Elizabeth beginning in 1933, eventually earning leadership positions in organisations such as the Commercial Travellers Union.[v] Now, he was fighting on behalf of black South Africans instead of his own people. The South African government responded to Weinberg’s actions in a variety of ways: they “listed” him for communist activity because of the Suppression of Communism Act, No. 44 of 1950, banned him from trade unions, placed him under house arrest, and imprisoned him for three months in 1960.[vi] In September 1964, Weinberg was arrested and detained for seven months because of his involvement with the South African Communist Party and Umkhonto we Sizwe, the Spear of the Nation (MK), which was the militant wing of the ANC. His work for these organisations included disseminating posters announcing MK’s formation on 16 December 1961, the day of the organisation’s first attacks. After a trial accusing him and thirteen other individuals of belonging to the party and wanting to overthrow the South African government, Weinberg received a five-year prison sentence.[vii] Upon his 1970 release, Weinberg still faced house arrest and banning orders, eventually escaping South Africa during the June 1976 Soweto uprisings at the direction of the ANC. He settled in Tanzania, where the national government provided him with political asylum until his death in 1981.[viii]

As illustrated through almost half a century of work on behalf of South Africa’s marginalised black community, Eli Weinberg’s selflessness and commitment to combatting inequality and inhumane behaviour was so great that he immersed himself in the anti-apartheid movement despite its personal irrelevance. His experiences with anti-Semitism imparted him with a hatred of all forms of racism and a passion for eradicating the discrimination of all people.

While on trial in 1964, Weinberg even publicly stated that his Jewish identity influenced his work for South Africa’s marginalised black community. He cited his encounters with anti-Semitism and the murders of his mother and sister in the Holocaust as feeding his opposition to South Africa’s systematic and covert racism.[ix] In an article written for The Rand Daily Mail three years earlier, Weinberg wrote, “As one of the many Jews whose families were exterminated in the name of race superiority, I must refuse to a pledge committing me to be loyal to a Republic blatantly based on racial domination.”[x] Weinberg also seemed similarly influenced by his religious beliefs. In a letter written to the Jewish Times in 1961 that argued the importance of helping those negatively impacted by apartheid, Weinberg quoted Old Testament passages such as “love thy neighbour” and talked about the Bible’s commandment to welcome strangers because of the Israelites’ experiences in Egypt.[xi]

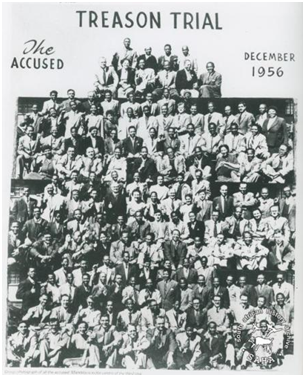

Eli Weinberg was not the only individual whose politics were shaped by his Jewish identity. Several other South African Jews came to prominence in the fight against racism, particularly with the advent of apartheid in 1948. Countless Jews played significant roles in labour and trade unions and the Communist Party of South Africa. The Jewish unions were some of South Africa’s first unions to include workers of all backgrounds, including Coloured and black individuals.[xii] For example, the Food and Canning Workers Union (FCWU), typically associated with Ray Alexander Simons, a Jewish woman born in Latvia like Weinberg, recruited both black and white members.[xiii] Jewish immigrants also heavily saturated the International Socialist League (ISL), which helped found the Communist Party of South Africa, the only political party that accepted black individuals.[xiv] Additionally, Jewish figures gained publicity and press for their involvement in high-profile events such as the Treason Trial, a legal case against 156 individuals charged with high treason (a capital offense in South Africa) after policemen raided homes and arrested members of Congress Alliance and other associated organisations on 5 December 1956.[xv] Twenty-three of the accused individuals were white, fourteen of whom who were Jewish.[xvi] All of the Jewish defendants had been involved with the Communist Party of South Africa before it was outlawed in 1950, and many had since joined the new South African Communist Party, formed in 1953. Jews also comprised a high percentage of the legal team defending those on trial and the groups fundraising in support of the accused – two trustees and seven of the original twenty-two sponsors of the Treason Trial Defence Fund were Jewish.[xvii] In a sense, Eli Weinberg himself even played a role in the Treason Trial; he took the famous photograph depicting the 156 defendants sitting together.[xviii]

Weinberg witnessed the racism he so despised even when taking this photograph in Joubert Park – in Portrait of a People: A Personal Photographic Report of the South African Liberation Struggle, a compilation of his surviving New Age photography, Weinberg relates how the park’s superintendent refused to let Weinberg bring in black people and photograph them sitting next to whites. As a result, the above photograph is a montage; Weinberg took photographs of groups of thirty-five to forty defendants and spliced them together (Treason Trial: The Accused, December 1956. Photograph by Eli Weinberg. Permission: South African History Archive and Africa Media Online)

Other prominent events and trials also reflect Jewish involvement in the anti-apartheid struggle and communist affairs. On 11 July 1963, police raided Arthur Goldreich’s Lilliesleaf Farm in Rivonia and arrested seventeen leaders of MK. All five of the whites captured in this raid – Goldreich, Denis Goldberg, Lionel Bernstein, Bob Hepple, and Hilliard Festenstein – were Jewish. The 1964 trial accusing fourteen people of communist sympathies and political subterfuge featured four Jews – Weinberg, Norman Levy, Esther Barsel, and Hymie Barsel.[xix]

Like Weinberg, many of the Jews involved in unions, communist parties, and other anti-apartheid organisations and operations cite their Jewish identities as influential and formative in their political behaviour. Though a few drew inspiration from religious and biblical teachings, most were inspired by Judaism’s ethnic and historical features; they felt empathy towards South Africa’s black population as a result of their ancestors’ or their own experiences with violence, marginalisation, anti-Semitism, and homelessness in Eastern Europe, particularly through the pogroms or the Holocaust.[xx] Those that personally escaped Europe and immigrated to South Africa felt like outsiders in South Africa, similar to the black community’s perceptions on their place alongside the country’s politically dominant Afrikaner population. Some Jews also empathised with South Africa’s racially marginalised populations because they saw parallels between Nazi ideology and Afrikaner nationalism – both were steeped in notions of racial superiority.[xxi] Ray Alexander Simons, who was born in Latvia in 1913, moved to South Africa in 1929 and was married to Eli Weinberg from 1937 until 1940. She became active in the Communist Party of South Africa and the South African Trades and Labour Council for many of these reasons.[xxii] On her involvement with communist parties in both Latvia and South Africa, Simons said, “I believed then that socialism is the correct response to anti-Semitism.”[xxiii] Likewise, Ben Turok, a central figure in the trade unions and one of the accused in the 1956 Treason Trial, was shaped by his Jewish identity and upbringing. Born in Latvia in 1927, Turok and his family fled for Eastern Europe in 1934 due to the pogroms and violence. In his new Cape Town community comprised of other Jewish refugees from Latvia, “the discussion was always about Jewish culture and the history of the Jewish people. So I imbibed a certain liberalism on racial issues.”[xxiv]

For many Jewish activists, their political views and commitment to eradicating apartheid were the result of inspiration from the South African Jewish communities they lived in; after all, a significant number of Jews fighting against apartheid were born in South Africa and therefore had no personal experience with Eastern European anti-Semitism or events like the Holocaust. These working-class immigrant communities, located in Cape Town and the Johannesburg area (Doornfontein, Yeoville, and Hillbrow in particular), engendered communist tendencies – their economically struggling inhabitants had brought their ideologies and socialist organisations with them from Eastern Europe.[xxv] These communities’ separation from the rest of society established an empathy and understanding towards black South Africans, and created some resentment towards the more successful Afrikaner population – acts such as setting up separate government schools for Jews increased the sense of marginality in relation to the rest of the white population.[xxvi] Additionally, this division helped immigrants maintain their unique culture. As a result, those growing up in South Africa’s Jewish immigrant neighbourhoods were frequently exposed to communist beliefs. For instance, Denis Goldberg, a defendant in the Rivonia Trial that helped manufacture devices used by MK, was born in Cape Town in 1933 and credits his upbringing in this immigrant community as the primary influence for his political stance and actions. While growing up, his family’s home was “open to anybody in the Party, in the ANC, in the Liberation Movement, the People’s Club…”[xxvii] In his autobiography, Joe Slovo, Communist Party member, founder of MK, and Treason Trial defendant and lawyer, described how his time in South African Jewish immigrant communities similarly affected his political activism.[xxviii] When living in a boarding house in Hillbrow after his family’s emigration from Lithuania, Slovo met Dr Max Joffe, the first member of the South African Communist Party that he had ever met. Slovo describes how Joffe often “talked of votes for blacks and his opposition to the ‘imperialist’ war. He planted the first seed of political interest in me.”[xxix] Slovo also called the general culture of immigrant communities an influence, stating that his “leanings towards leftist socialist politics was also formed partly by the bizarre and paradoxical embrace of socialism shared by most of the immigrants who filled the boarding houses in which we lived.”[xxx]

Because of the prevalence of communist beliefs in Jewish communities and the prominence of Jews in highly publicised trials, Jews were seen as heavily involved in the anti-apartheid struggle. Over half of the white defendants in the Treason Trial and all of the whites arrested at Lilliesleaf Farm were Jewish, which established an unshakeable public impression that Jews always allied themselves with communism and anti-apartheid causes.[xxxi]Nelson Mandela reaffirms this idea in his autobiography – since a Jewish law firm willingly took him on as a clerk despite his skin colour, Mandela writes that “I have found Jews to be more broad-minded than most whites on issues of race and politics, perhaps because they themselves have historically been victims of prejudice.”[xxxii] Society’s belief in an association between Jews and anti-apartheid stances led to suggestions that Jews desired to subvert the government and were therefore unreliable.[xxxiii]

However, these high profile Jewish anti-apartheid activists do not make up the whole story – not all Jews chose to participate in the movement. Instead, rabbis and organisations such as the Jewish Board of Deputies avoided participation in politics and encouraged all Jews to act similarly. Editors of Jewish newspapers and the Jewish Board of Deputies even ostracised members of their own community participating in communist activities, including Eli Weinberg, by publishing accounts that condemned their actions and suggested that they betrayed South Africa and the Jewish community.[xxxiv] Only in 1985 did the Jewish Board of Deputies change its course and release a statement that denounced apartheid and proclaimed the organisation’s “commitment to justice, equal opportunity, and removal of all provisions in the laws of South Africa which discriminate on grounds of colour and race.”[xxxv] The Jewish community’s overall abandonment of the anti-apartheid movement and its allies was partially the result of the lack of necessity to provide campaign assistance. For once, Jews were not the primary subject of discrimination; under the apartheid regime, skin colour determined societal position and Jews met the Afrikaner standard. Because of this, South African Jews even benefitted from potential financial mobility.[xxxvi] Additionally, many Jews avoided and disliked the anti-apartheid movement because they feared anti-Semitism – after all, their people had experienced discrimination for millennia through situations as severe as the Holocaust. Their worry over potential anti-Semitism in South Africa was not entirely unfounded; the government had taken some anti-Jewish stances. In 1930, the National Party, which did not allow Jewish members in its Transvaal section, instituted the Immigration Quota Bill, which limited the number of immigrants from Russia, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, and Palestine. Dr Daniel F. Malan, head of the National Party, said in a 1937 speech that “there are too many Jews here, too many for South Africa’s good and too many for the good of the Jews themselves.”[xxxvii] Three years later, Malan also reminded the Jews that “that they were guests in South Africa.”[xxxviii] However, by 1947, the National Party reversed its anti-Semitic approach as it geared up for the landmark 1948 elections that led to the institution of apartheid; Die Burger published a statement made by Malan in which he explained that his party did not support discriminatory actions towards Jews.[xxxix]

As a result of this change, Jews remained silent about apartheid for decades to come. Though understandable because of Jewish fears of prejudice in South Africa, this lack of action also seems shocking and despicable considering the Holocaust’s discriminatory destruction of European Jewry. Often, Jews question how gentiles could stand idly by as millions of innocent individuals were legally removed from their homes, trapped in ghettos, transported in cramped cattle cars, and methodically exterminated or used in work camps. They also insist on always remembering the Holocaust in order to prevent its recurrence. However, many of these same Jews acted similarly regarding apartheid; they simply watched as the South African government systematically marginalised blacks throughout all aspects of life and relegated those brave enough to take a stance.[xl]

Though they may not have been representative of South Africa’s Jewish community as a whole, Eli Weinberg and several South African Jewish figures epitomise their religious culture in several ways, embodying it in their embrace of anti-apartheid politics and activism. They were capable of empathising with those experiencing marginalisation in their own communities, a theme very relevant to Jewish anti-apartheid advocates. Many experienced exile two or three times over – from Europe, from Africa, and from their own unaccepting Jewish community. Jews like Weinberg, Ray Alexander Simons, and Ben Turok, who fled Europe with their families due to anti-Semitism and political unrest, were later exiled to Tanzania, Zambia, and London because of their involvement in activism in South Africa.[xli] In the Talmud, Judaism’s revered Hillel famously said, “And if I am only for myself, what am I? And if not now, when?”[xlii] Jewish anti-apartheid figures like Eli Weinberg truly embody this teaching – they selflessly experienced several exiles because they responded to immediate calls of action against a discriminatory political system not even personally harming them. These individuals could have taken the easy route and ignored the plight of those impacted by apartheid; instead, they bravely assisted the fight against apartheid at their own expenses, accepting the resulting prison sentences and lifelong exclusion. Their stories serve as inspirations to all, both Jewish and gentile.

Works Cited

Primary Sources:

Mandela, N., (1994). Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela, New York: Little, Brown and Company.

Simons, R. A., (1993 and 1996). Interview Steven Robins and Immanuel Suttner. Available at http://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/ray-alexander-simons-interviewed-steven-robins-and-immanuel-suttner-20-july-1993-and-january [Accessed 26 October 2016]

Turok, B., (2006). Interviewed by David Wiley for South Africa: Overcoming Apartheid, Building Democracy, 12 May [online] Available at http://overcomingapartheid.msu.edu [Accessed 24 October 2016]

Slovo, J., (1997). Slovo: The Unfinished Autobiography, Melbourne and New York: Ocean Press.

Weinberg, E., (1956). Treason Trial: The Accused, December 1956, photograph, www.biznews.com[Accessed 26 October 2016]

Weinberg, E., (1981). Portrait of a People: A Personal Photographic Report of the South African Liberation Struggle, London: International Defence and Aid Fund for Southern Africa.

Secondary Sources:

Cesarani, D., Kushner, T., & Shain, M., eds., (2009). Place and Displacement in Jewish History and Memory: Zakor v’Makor, London and Portland: Vallentine Mitchell.

Cohen, R., (2015). The Girl from Human Street: Ghosts of Memory in a Jewish Family, New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Dribins, L., (2014). ‘Latvia’s Jewish Community: History, Tragedy, Revival’ from Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Latvia [online] Available at http://www.mfa.gov.lv/en [Accessed 27 October 2016]

Ethics of the Fathers (Pirkei Avot). [online] Available at http://www.chabad.org [Accessed 19 November 2016]

Keller, B., (1995). ‘Joe Slovo, Anti-Apartheid Stalinist, Dies at 68,’ The New York Times, 7 January. [online] Available at http://www.nytimes.com [Accessed 19 November 2016]

Lukas, J., (1964). ‘South Africans on Trial as Reds,’ The New York Times, 17 November. [online] Available at http://www.nytimes.com [Accessed 30 October 2016]

Shimoni, G., (1980). Jews and Zionism: The South African Experience (1910-1967), Cape Town: Oxford UP.

Shimoni, G., (2003). Community and Conscience: The Jews in Apartheid South Africa, Hanover and London: UP of New England.

South African History Online, (2013). ‘Eli Weinberg’ from South African History Online. [online] Available at http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/eli-weinberg [Accessed 20 October 2016]

Suttner, I., ed. (1997). Cutting Through the Mountain: Interviews with South African Jewish Activists, London: Viking Penguin.

Tatz, C., (2007). Worlds Apart: The Re-Migration of South African Jews, Australia: Rosenberg Publishing Pty Ltd.

End Notes

[i] South African History Online, “Eli Weinberg,” South African History Online, 2013, last modified 18 November 2016. http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/eli-weinberg; Eli Weinberg, Portrait of a People: A Personal Photographic Report of the South African Liberation Struggle, (London: International Defence and Aid Fund for Southern Africa, 1981). 5. ↵

[ii] Weinberg, 6. ↵

[iii] Colin Tatz, Worlds Apart: The Re-Migration of South African Jews (Australia: Rosenberg Publishing Pty Ltd., 2007). 14. ↵

[iv] Leo Dribins, “Latvia’s Jewish Community: History, Tragedy, Revival,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Latvia, last modified 12 February 2014. http://www.mfa.gov.lv/en ↵

[v] Weinberg, 5; Gideon Shimoni, Jews and Zionism: The South African Experience (1910-1967) (Cape Town: Oxford UP, 1980). 233. ↵

[vi] South Africa History Online; Weinberg, 5. ↵

[vii] Weinberg 5; South Africa History Online; J. Anthony Lukas, “South Africans on Trial as Reds,” The New York Times, 17 November 1964, http://www.nytimes.com ↵

[viii] South Africa History Online; Weinberg, 5. ↵

[ix] Gideon Shimoni, Community and Conscience: The Jews in Apartheid South Africa (Hanover and London: UP of New England, 2003). 69, 233. ↵

[x] Shimoni, Community and Conscience: The Jews in Apartheid South Africa, 104-5. ↵

[xi] Shimoni, Community and Conscience: The Jews in Apartheid South Africa, 105. ↵

[xii] Shimoni, Community and Conscience: The Jews in Apartheid South Africa, 8. ↵

[xiii] Immanuel Suttner, ed., Cutting Through the Mountain: Interviews with South African Jewish Activists (London: Viking Penguin, 1997). 23. ↵

[xiv] Shimoni, Community and Conscience: The Jews in Apartheid South Africa, 9. ↵

[xv] Weinberg, 148. ↵

[xvi] Roger Cohen, The Girl from Human Street: Ghosts of Memory in a Jewish Family (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2015). 133. ↵

[xvii] Shimoni, Community and Conscience: The Jews in Apartheid South Africa, 60-1. ↵

[xviii] Treason Trial: The Accused, December 1956. ↵

[xix] Shimoni, Community and Conscience: The Jews in Apartheid South Africa, 64-5, 69. ↵

[xx] Suttner, vii, 2. ↵

[xxi] Tatz, 131. ↵

[xxii] Suttner, 23. ↵

[xxiii] Ray Alexander Simons, interviewed by Steven Robins and Immanuel Suttner, South African History Online, 1993 and 1996. http://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/ray-alexander-simons-interviewed-steven-robins-and-immanuel-suttner-20-july-1993-and-january ↵

[xxiv] Ben Turok, interviewed by David Wiley, South Africa: Overcoming Apartheid, Building Democracy, 12 May 2006. http://overcomingapartheid.msu.edu. 2:42. ↵

[xxv] Slovo, 28; David Cesarani, Tony Kushner, and Milton Shain, eds., Place and Displacement in Jewish History and Memory: Zakor v’Makor (London and Portland: Vallentine Mitchell, 2009). 172. ↵

[xxvi] Shimoni, Community and Conscience: The Jews in Apartheid South Africa, 79. ↵

[xxvii] Suttner, 467. ↵

[xxviii] Slovo, 2, 27-8; Bill Keller, “Joe Slovo, Anti-Apartheid Stalinish, Dies at 68,” The New York Times, 7 January 1995, http://www.nytimes.com ↵

[xxix] Slovo, 32. ↵

[xxx] Shimoni, Community and Conscience: The Jews in Apartheid South Africa, 80. ↵

[xxxi] Shimoni, Community and Conscience: The Jews in Apartheid South Africa, 60, 62. ↵

[xxxii] Nelson Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1994). 71. ↵

[xxxiii] Shimoni, Jews and Zionism: The South African Experience (1910-1967), 234. ↵

[xxxiv] Tatz, 122. ↵

[xxxv] Cohen, 131. ↵

[xxxvi] Shimoni, Community and Conscience: The Jews in Apartheid South Africa, 1-3. ↵

[xxxvii] Cohen, 126. ↵

[xxxviii] Shimoni, Community and Conscience: The Jews in Apartheid South Africa, 16. ↵

[xxxix] Shimoni, Community and Conscience: The Jews in Apartheid South Africa, 22. ↵

[xl] Cohen, 129. ↵

[xli] Suttner, 24; Turok. ↵

[xlii] Ethics of the Fathers (Pirkei Avot), 1:14, accessed 19 November 2016. http://www.chabad.org ↵

This article forms part of the SAHO and Southern Methodist University partnership project