Nokukhanya Luthuli, maiden name Bhengu, (also known as MaBhengu) was the wife of Chief Albert John Luthuli. Although she never became as public a figure as her husband was, she was significant in her own right and made a considerable contribution to her community and South Africa’s liberation struggle as a whole. Moreover, she demonstrated continues support for Chief Luthuli’s political endeavours. He dedicated his autobiography partly to her and therein expressed great admiration for her and gratitude for her role in his life. The late president Nelson Mandela also made a personal speech honouring her contribution to South Africa at her funeral in December 1996.

Early Years

Nokukhanya Bhengu was born on 3 March 1904 at the Umngeni Mission Station (near Durban) as the youngest daughter of Maphitha and Nozincwadi Bhengu. Nokukhanya was considered of royal blood, since she was the granddaughter of the Zulu Chief Dhlokolo Bhengu of the Ngcolosi. Her father, Maphitha, was a convert of the Umngeni American Board Mission and began a line of Christian believers in his family. Nokukhanya recalled that her parents were eager to spread Christianity from within the family and that her name (meaning “mother of light”) demonstrated their wish that she should grow up as a bringer of light. She had a Congregationalist upbringing, and her family was relatively wealthy for their time. Nokukhanya described her mother, Nozincwadi, (also known as MaNgidi), as very interested in education. She recalled her also running a shop. It is unclear who the official owner of this shop was, but Maphitha seems to have built it for his wife, at her request, after an operation prevented her from doing manual labour. The shop stocked, among other items, Indian foods and spices, which were much loved in the region.[1]

Nokukhanya shared her mother’s passion for education and thereby gaining a better life for herself and her loved ones. Her formal education began in 1913 at Ohlange Institute. Rev. John Dube, founding member and first president of the African National Congress (ANC), founded this school in 1900. He was also a friend of the Bhengu family. Dube’s institute became the first Black-directed institution and differed from other missionary schools in that the learners were encouraged to read in their own language as well as to concentrate on practical aspects of the curriculum.[2] Although the school had male and female pupils, males seemed to have been the majority. Nokukhanya recalled the school being poor, and resources being scarce. Together with a few other young girls, she would get up each morning at 4 A.M. in order to help their teacher, Miss Blackburn, with housework before school.[3]

Nokukhanya’s education at Ohlange Institute was disrupted when she lost her mother at the age of ten and had to return to the Umngeni Reserve. Furthermore, when her father took Sedi Khanyeza as his second wife, she seemed remarkably unconcerned with the children from his first marriage. Consequently, Nokukhanya gradually grew estranged from her father and ultimately went to live with her elder brother. Her father also refused to support her formal education further. He considered it a waste, since she would be married and have a husband who could provide for her. Nevertheless, he agreed that, if she found a way to pursue her formal education further independently he would not stand in her way.[4]

The 1917, girls’ building at the Ohlange Institute. Since Nokukhanya probably left the school around 1914, it’s reasonable to assume she was also taught in this building. Image source

The 1917, girls’ building at the Ohlange Institute. Since Nokukhanya probably left the school around 1914, it’s reasonable to assume she was also taught in this building. Image source

Along with eight other girls, Nokukhanya subsequently made an agreement with the headmistress of Inanda Seminary, Miss Evelyn Clark, which would allow her to further her education despite her lack of funds. Under their agreement, she would pay her school fees of five pounds per term by working for the school. This arrangement of studying in exchange for work done at the school was only available to a few students and her teacher had to apply on her behalf.[5]

Nokukhanya recalled her time at Inanda Seminary as a period of poverty and extreme hard work. The other students often had new clothes or other items she simply could not afford. Nonetheless, she also remarked that they were taught not only to pass their classes but were “given an education for life,” receiving domestic and industrial training; such as sewing and the like. She became an excellent pupil and ended each year among the top of her class despite her extra work to pay school fees. At the end of her standard seven year, Miss Clark recommended her to the principle of Adams College, Albert LeRoy, for a teachers training course. Thus, in 1920 she began her teachers training at Adams College. She subsequently began teaching at Mpushini near Pietermaritzburg in 1922 and also taught at Inanda Day School later that same year. In 1923, she returned to Adams College as part of the staff, while simultaneously completing her higher teachers’ diploma.[6]

Marriage and Family Life

In 1925, Nokukhanya met Albert Luthuli at Adams College when she became one of his students in Zulu and school organization class. They began a courtship some months later. Interestingly, they were also together in school at Ohlange Institute without being aware of each other at the time. Nokukhanya rejected an initial proposal, wanting them to take more time to make the decision, and ensure that they were compatible in terms of personality and desires for the future. She later recalled having told him: “we must take time with this decision, because what we are aiming at, a lifetime together, is really quite a long time.” During this time, she particularly appreciated his manner of approach and the fact that he did not pester her to receive a response. After eight more months of courtship, she agreed to become his wife.[7] They were married on 19 January 1927. After the marriage, Nokukhanya resigned from her posts as teacher at the Adams Practicing School and as a staff member at the Adams Hostel for girls. She departed from Adams College in order to establish a home for them at Groutville.[8]

Groutville is located about ten kilometres to the south of KwaDukuza, between Stanger and Durban. The village was named for its first missionary, Aldin Grout from the American Board of Commissioners, following his death in 1894. It was formerly known as the Umvoti Mission Reserve, since Grout established the mission station near the Umvoti River in 1845. Interestingly, Groutville differed from other native reserves in some important ways. Firstly, the people of Groutville used democratic means to elect their chiefs. The chieftainship was therefore not inherited, as was the case with traditional Zulu chieftains. Furthermore, the distinction between male and female work tended to disappear, or at least become less definite. The village also seemed to lack an elite class and class distinction, and was primarily known for farming, particularly sugar cane. Of the first seven Chiefs of the Umvoti Mission reserve, four were Luthulis. Thus, Groutville, the traditional home of the Luthulis, also became home to the next generation.[9]

Originally, the newlyweds did not have a home of their own. They lived in the house of Albert’s cousin Martin for nearly two years while their home was being built, moving in late in 1928. The couple lived separately for the first eight years of their marriage due to the political restrictions placed on Africans in cities during this time. Moreover, Nokukhanya provided Albert’s mother, Nozililo, who was very ill at the time, with the necessary care until her death in 1932.[10] Nevertheless, when reflecting upon this period in his autobiography, Albert considered them fortunate, since this state of separation could very well have continued for the rest of their lives if he had not become chief of Groutville.[11]

Between 1929 and 1945, Nokukhanya and Albert had seven children (three boys and four girls). Their eldest son, Hugh Bunyan Sulenkosi was born in March 1929. He was also the only one of their children to be born in a hospital. The other children were all born at home with the help of a nurse aid or trainee. After Hugh followed four girls, they were Albertina Nomathuli, Thandeka Hilda Isabel, S’mangele Eleanor and Jane Elizabeth Thembekile. The last two children were sons, Christian Madunjini and Sibusiso Edgar.[12] Many years later, Nokukhanya still maintained that she “could not have married a better man,”[13] and Albert held a similar high opinion of his wife, counting himself “fortunate among men” to have married her.[14]

Albert ended his career as a teacher when he became Chief of Groutville in 1936. He initially declined the Chieftainship for two years, believing that his true contribution lay in teaching and knowing that he could better provide for his family with a teacher’s salary. Moreover, he was concerned with his youth and consequent lack of experience. He had also seen other members of his family, among them his uncle Martin, head the affairs of Groutville as Chief and he had no desire to follow their example. He had a rather sudden change of heart however, which he attributed partially to the emphasis placed on service to the community during his time at Adams. Nokukhanya also came to the realization that their family could best serve the community through Albert’s Chieftainship. He was subsequently democratically elected as Chief from among four candidates, and his appointment was approved by the Native Commissioner. This allowed him to leave Adams and remain with his family permanently after eight years of separation.[15]

The restrictions placed on married women teachers forced Nokukhanya to quit teaching entirely soon after her marriage. She realized however, with Albert’s appointment to the Chieftainship, that she would need to supplement their family income in order to see her children properly educated. She also recognized that Albert could not assist her in this regard, as his income as Chief was minimal, and his duties often took him away from home.[16]

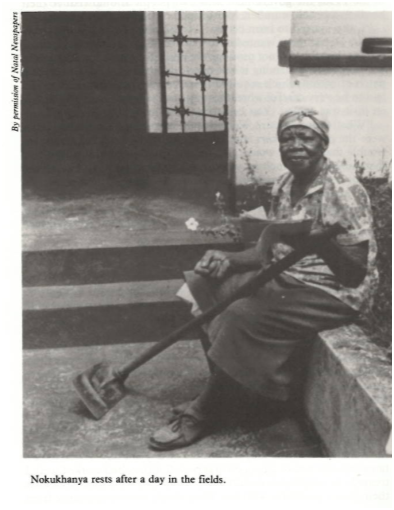

Thus, working the land became her only means of generating additional income. She became well known as a determined and productive farmer in her community, working several hectares of land near the Unvoti River. Her labour yielded various crops over the years, including various vegetables and even rice for some years. She was never stingy and often shared her produce with neighbours and friends, inviting them to fetch fresh vegetables from her home when she had harvested them. At times, she hired casual labourers to help with weeding the land and Albert’s aunt, MaDladla, sold the produce in Durban. She used the profits from these sales to build up capital to begin sugar cane farming in 1934.[17] As the children grew older, sugar cane farming and tending vegetable gardens became a family affair in which everyone played their part. Albertina later recalled how her mother instilled in them the importance of hard work from a young age. She acknowledged that “to a large extent we are what we are today because of it.” In later years, it grew difficult for Nokukhanya to maintain the farm labour independently, and she was forced to cease production on some of the more labour intensive crops (such as rice) while the children were at boarding school.[18]

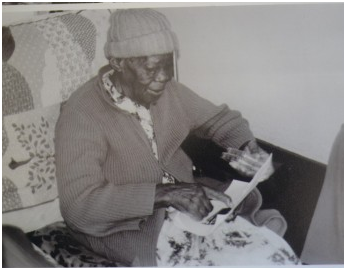

Nokukhanya resting after a day of working in the fields. Source: Rule, P, Aitken, M. and Van Dyk, J.: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, The Grail, Braamfontein, 1993.

Nokukhanya resting after a day of working in the fields. Source: Rule, P, Aitken, M. and Van Dyk, J.: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, The Grail, Braamfontein, 1993.

The extra income enabled the Luthulis not only to care for their own children, but also to take in other family members as the need arose. Among them were Willie and Charlotte Luthuli. Willie was Albert’s brother Alfred’s son, the Luthulis took him in after his parents separated and his father had to work in an environment not ideal for a young boy. Charlotte was the daughter of Albert’s uncle Daniel and the family took her in following the death of her father.[19]

Nokukhanya’s main objective in raising her children always remained ensuring that they were ready for anything life could send their way. This philosophy, together with her outspoken belief in gender equality, motivated her to do away with many of the traditional gender roles in the world of work that were common for this period. Both boys and girls were required to work in the household on tasks such as cooking, cleaning and doing laundry as well as in the fields as farmers. They recall their childhood as filled with hard work and discipline.

Nevertheless, they also praise their mother for her kindness. Jane particularly recalled her mother’s concern for the individual and her ability to raise each of her children as unique individuals. Within their household, there was time for homework as well as play and the evenings were always family time, which included sharing the day’s events and having Bible study. When Albert was home he also often shared in the housework, and the children loved spending time with him. Nokukhanya also appreciated the fact that he never restricted what she wanted to do for the upkeep of their home, and he did not attempt to gain control of her finances or farming profits.[20] When speaking of their home in his autobiography Albert praised Nokukhanya for creating for their family “the one place of relative security and privacy which we know.”[21] Thus, despite hard work and relative poverty, they were, overall, a happy and loving family.

Political Involvement

Following his appointment as Chief, Albert Luthuli became increasingly involved in politics. Becoming Chief allowed him to see first-hand the hardships that his community was faced with daily. The function of a Chief during this period included, among other things, administrative duties, acting as magistrate in civil affairs and serving as a liaison between the Native Commissioner and the tribe. As Chief, he acted as judge, police chief, counsellor, and ombudsman on different occasions. The year 1936 was a particularly challenging time to accept such responsibilities due to the recent passing of the Hertzog Bills. The passing of these laws led to further hardships for all non-whites, specifically regarding land. Despite the challenges of this period, Albert gained a reputation as a just man and became a well-liked and respected Chief. He attempted to involve the whole community in decision-making that would influence their lives and he never accepted bribes to sway his judgement in cases. During his time as Chief, he also spoke in India and the United States on behalf of the Christian missions.[22]

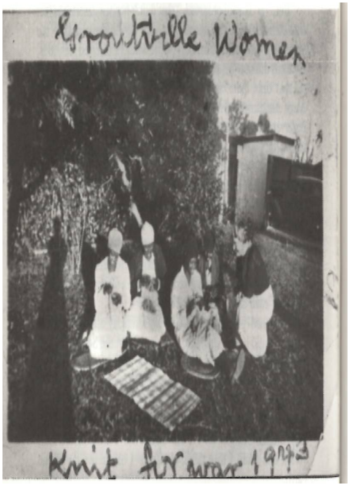

The Luthuli family also regularly received important guests during Albert’s Chieftainship, and Nokukhanya was always a generous hostess. However, her contributions were not made merely from the sidelines. She became actively involved in Daughters of Africa, an organization started by Dr Dube’s wife, Angeline to encourage woman to become involved in political matters. The organization was particularly active during the Second World War (WWII) holding meetings to keep people informed and workshops to knit for the soldiers. The ANC encouraged its members to participate in the war, hoping that this might lead to more domestic freedoms once the war was won. Daughters of Africa also helped teach women skills, such as cooking and sewing. It served as a forerunner to the ANC Women’s League. Besides this, Nokukhanya was also involved in her local church, and she opened a post office in her home in 1945 after it became known that the postmaster stole the money that the people of Groutville were attempting to send by post. She was respected as a leader in her community and others often turned to her for advice.[23]

Women of Groutville, knit for the soldiers as part of the Daughters of Africa. Source: Rule, P, Aitken, M. and Van Dyk, J.: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, The Grail, Braamfontein, 1993.

Women of Groutville, knit for the soldiers as part of the Daughters of Africa. Source: Rule, P, Aitken, M. and Van Dyk, J.: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, The Grail, Braamfontein, 1993.

At first, Albert was a representative for the interests of the Groutville community of mainly sugar cane farmers, but he gradually played an increasingly prominent role within the ANC. In 1945, he was elected onto the Natal executive of the ANC. Following the death of Dr Dube, he was also increasingly involved in the Native Representation Council. In December 1952, he was elected President-General of the ANC and in the same year, the government stripped him of the chieftaincy due to his political activities.[24]

Albert was subsequently involved in many actions of resistance as head of the ANC and the government often acted against him and his family through police raids, arrests and other measures. Many relatives advised Nokukhanya to encourage her husband to retire from politics due to the ever-increasing danger. She considered it wrong to do this however, because “someone had to take action and not shrink from the responsibility to advance the cause of our people.”[25] Albert regularly expressed his appreciation for having her at his side both in his private and public life.

On Saturday 26 March some sources 27 March 1960, Albert publically burned his pass in Pretoria and encouraged all Africans to peacefully do the same. He was under a strict ban at the time, but was required to be in Pretoria to provide evidence for his trial. He called for a nationwide stay-at-home on 28 March, as a national day of mourning, protest and prayer for the atrocities that occurred at Sharpeville on 21 March, when 69 unarmed protesters were killed and many more wounded by the South African Police Force. Many heeded his call and it became a multi-racial initiative. All across the country, churches opened for prayer for the Sharpeville victims and the situation in South Africa.[26]

Albert Luthuli publicly burning his pass in Pretoria. Image source

Albert Luthuli publicly burning his pass in Pretoria. Image source

The National Party (NP) government responded to this by declaring the country’s first state of emergency on 30 March 1960. The state of emergency was declared in 80 of the 300 magisterial districts, including every important urban area. This gave the government broad powers to act against what it called “all forms of subversion.” The actions allowed under a state of emergency included the power to arrest and detain indefinitely any person suspected of “anti-government activity.” [27] The army was also called in to reinforce the police due to the state of emergency and regiments of the Citizens Force were mobilized. During this period, over 2,000 South Africans from among all races were arrested in connection with anti-government activities. Chief Luthuli was also arrested and detained until his trial in August. He was given a six-month suspended sentence and fined £100. Following the mass demonstrations in March, the Unlawful Organisations Act No. 34 came into effect on 7 April. Under this Act, any organisation deemed a threat to the public could be declared unlawful by the government. The government announced the following day that the ANC and the PAC have been banned under the Act. This state of emergency ended in August 1960.[28]

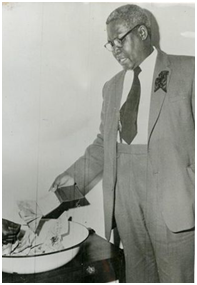

On 10 December 1961, Albert was awarded the 1960 Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo. Because the world’s attention was focussed on the award, the government decided to allow the couple to attend together. Large celebrations were also held in their community prior to their departure. During his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, Albert acknowledged the major role his wife plays in his life and political activities, and stated that she richly deserved to share the honour of receiving the prize with him. During the selection process in 1960, the Norwegian Nobel Committee decided that none of the year's nominations met the criteria outlined in Alfred Nobel’s will. According to the Nobel Foundation's statutes, the Nobel Prize can then be reserved until the following year. Albert Lutuli thus received his Nobel Prize for 1960 in 1961. He became the first African to receive the Nobel Peace Prize.

Nokukhanya Luthuli – Seen here receiving a taped version of her husband, Albert Luthuli’s Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, this photograph formed part of material donated to the Luthuli Museum in 2013. Image source

Nokukhanya Luthuli – Seen here receiving a taped version of her husband, Albert Luthuli’s Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, this photograph formed part of material donated to the Luthuli Museum in 2013. Image source

The Luthuli home also experienced the kinds of disagreements that one may find in many households. According to Albertina, some of the children felt somewhat ashamed of their home, compared with others. They approached their father about this, explaining that he hosted important guests from around the globe and should do so in a finer house. They also encouraged him to find a way of earning more money to do this. However, he was not convinced that there was anything wrong with the house. When the news of the Nobel Prize reached the family, the elder sisters started to imagine the home they would buy, one that would make them the envy of the rest of Groutville. Their imaginations came to a halt when almost all the money was spent on buying farms in Swaziland. Albert explained that individuals involved in the liberation struggle might have to leave the country and in such a situation, the ANC could make use of these farms. Following their acquisition, Nokukhanya would tend these farms from time to time, in order to ensure that they were not considered unoccupied by the Swazis. According to Thulani Gcabashe, her son-in-law, during the 1960s there were uMkhonto weSizwe (MK) recruits being cared for by Nokukhanya and other family members on these farms. In the 1960s, they were also able to take a lot of produce back to Groutville, although the farms collapsed in the 1970s.[29]

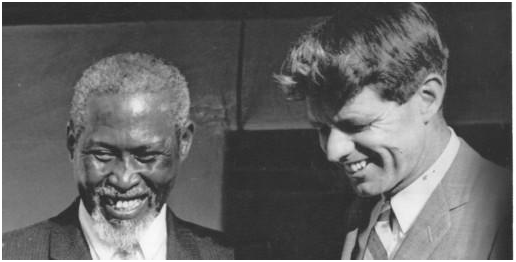

On 8 June 1966, Albert met US Senator for New York, Robert Kennedy, in his hometown. Kennedy and his wife, Ethel, landed at a nearby soccer field to meet the people of Groutville and their Chief. During their meeting, they discussed the problems facing the USA and the future of black South Africans. Kennedy later referred to Albert as one of the most impressive men he had met on his travels around the world. This meeting came towards the end of Kennedy six-day visit to South Africa, which began on 4 June 1996. Also during this visit, Kennedy gave his acclaimed “Ripple of Hope” speech at Stellenbosch University, on 6 June 1966. Not long thereafter, on 5 June 1968, Kennedy was assassinated.[30]

Chief Albert Luthuli with U.S. Senator Robert Kennedy, June 8, 1996. Image source

Chief Albert Luthuli with U.S. Senator Robert Kennedy, June 8, 1996. Image source

Later Years

On 21 July 1967, Albert Luthuli died in Stanger hospital after being struck by a freight train on a narrow railway bridge near his home in Groutville. He died at 2:29 pm while the majority of his family were still rushing to reach him. Nokukhanya recalled having a disagreement with him the previous day concerning her fear for his safety. Albert led the ANC up until his death. On 19 September 1967, an inquest into his death was held at Stanger Magistrate’s Court with Mr C. I. Boswell presiding. Mr Boswell ruled that there was no criminal culpability on the part of the South African Railways employees or any other person and that Albert did not appear to be aware of the approaching train. The family suspected that he was deliberately killed and was not satisfied with the investigation. According to Nokukhanya, he received several visits from the security police in the months leading up to his death. Moreover, he was still under a restriction order due to his political activities at the time of his death. Whether his death was entirely accidental thus remains unclear.[31] Suttner aptly describes him as having died in a “tragic and unresolved” manner.[32]

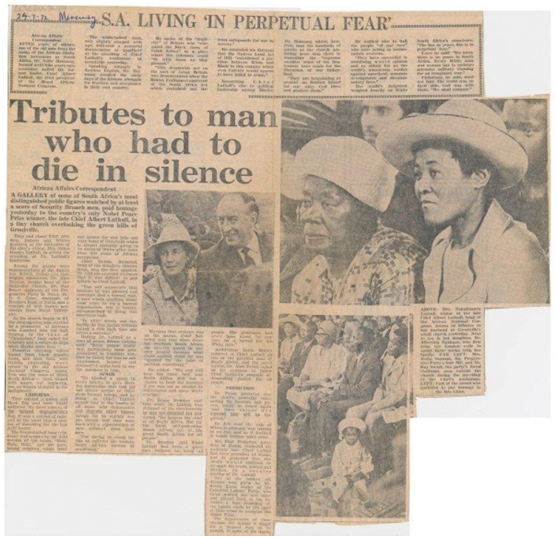

On 23 July 1972, five years after his death, his tombstone was unveiled at a small church in his hometown. Alan Paton was asked to give a memorial speech at the event and South Africans from across the country paid their respects. Overall, 13 speakers, including many well-known figures, paid tribute to the late Chief at the event. At the time of the unveiling, two of Chief Luthuli’s daughters were living in exile. Albertina was in Lesotho and Thandi was in the USA. Although Albertina could return briefly for the unveiling, the government refused to grant a visa to Thandi and both of their husbands, Thulani and Pascal.[33]

Original article reporting on the unveiling of Chief Albert Luthuli’s Tombstone. Image source

Original article reporting on the unveiling of Chief Albert Luthuli’s Tombstone. Image source

Nokukhanya remained active in her community and politics following her husband’s death. The community launched a particularly strong campaign against the planned forced removals, since the area they would have been sent to was 25 kilometres away, and it would require them to rebuild their lives and homes from scratch without any monetary aid. In 1985, they were finally informed that they would not be moved.[34]

In December 1976, she travelled to Jan Smuts Airport (O.R. Tambo International Airport today) in Johannesburg to go overseas for the first time in 15 years. She spent six months preparing for this journey to visit her daughter Thandi and her family who had been living in exile in Atlanta, USA since 1969. Her stay in the USA ended on 5 June 1977. After which, she was invited to revisit Norway. She also spent some time in London, finally returning to South Africa on 22 June 1977. During her travels, she met many exiles and religious and civil rights leaders. She also spoke often concerning the situation in South Africa at church meetings and other gatherings.[35]

On 16 December 1996, Nokukhanya Luthuli died at the age of 92. Speaking at her funeral in Groutville, the late president Nelson Mandela said: “Mama Nokukhanya shared the trenches of struggle with our beloved leader Chief Albert Luthuli … she was one of those leaders who contributed to our struggle away from the limelight. But she will go down in history as a member of the battalions of resilient women whose spirit could not be broken by the pain and suffering the apartheid government imposed on them.”[36]

“We are in a time when we need to turn, without blindness to the faults they may have or have had, to the lessons of exemplary leaders and reconsider what it is that we can learn and transmit to others. We need to build on this in order to inform our politics in a different way from that which currently prevails. There is, of course, a danger in notions like ‘exemplary leadership’ and one must be conscious of the need to avoid idealisation.”[37] Raymond Suttner made the above statement in his article examining Chief Albert Luthuli's life. Any in-depth investigation into Chief Luthuli's life will swiftly reveal that, although he certainly deserves recognition as a leader of his time, he was far from solely responsible for his achievements. Among those who aided him and his work, his wife certainly deserves particular recognition. Not merely for her invaluable contributions in all his endeavours, but also as an ‘exemplary leader’ in her own right.

End Notes

[1] P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, pp. 17-19, 23. ↵

[2] South African History Online, “The Ohlange School founded by John Dube,” http://www.sahistory.org.za/topic/ohlange-school-founded-john-dube ↵

[3] P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, pp. 27-28. ↵

[4] P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, pp. 28-29. ↵

[5] P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, p. 29. ↵

[6] P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, pp. 32, 36-37. ↵

[7] P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, pp. 40-41. ↵

[8] A. Luthuli: Let my people go, an autobiography, pp. 43-44. ↵

[9] P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, p. 53. ↵

[10] P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, pp. 57-58. ↵

[11] A. Luthuli: Let my people go, an autobiography, p. 44. ↵

[12] P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, p. 58. ↵

[13] P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, p. 45. ↵

[14] A. Luthuli: Let my people go, an autobiography, p. 44. ↵

[15] A. Luthuli: Let my people go, an autobiography, pp. 54-56. ↵

[16] P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, pp. 57, 59. ↵

[17] P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, pp. 59-60. ↵

[18] P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, pp. 62, 68. ↵

[19] P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, pp. 66-67. ↵

[20] P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, pp. 72, 74, 77. ↵

[21] A. Luthuli: Let my people go, an autobiography, p. 44. ↵

[22] D. C. Woodson: “Albert Luthuli and the African National Congress: A Bio-Bibliography,” History in Africa (13), 1986, pp. 346-347. ↵

[23] P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, pp. 96. 99-100. ↵

[24] P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, pp. 102-104. ↵

[25] P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, pp. 104-106. ↵

[26] The Nelson Mandela Foundation: Living the Legacy, “Foundation remembers Sharpeville Massacre victims,” https://www.nelsonmandela.org/news/entry/foundation-remembers-sharpeville-massacre-victims. Published on 19 March 2010, Accessed on 02 February 2017. ↵

[27] Oakes, D.: “Anger that sparked 16km Parliament march,” Cape Times, http://www.iol.co.za/capetimes/anger-that-sparked-16km-parliament-march-2031739 ↵

[28] South African History Online, “African National Congress (ANC) Timeline 1960-1969,” http://www.sahistory.org.za/topic/african-national-congress-timeline-1960-1969 ↵

[29] R. Suttner: ‘“The Road to Freedom is via the Cross’ ‘Just Means’ in Chief Albert Luthuli's Life,” South African Historical Journal (62), (4), 2010, p. 702. ↵

[30] S. Mtshali: “When Kennedy met Luthuli,” Daily News, http://www.iol.co.za/dailynews/opinion/when-kennedy-met-luthuli-2028227, ↵

[31] P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, pp. 140-142. ↵

[32] R. Suttner: ‘“The Road to Freedom is via the Cross’ ‘Just Means’ in Chief Albert Luthuli's Life,” South African Historical Journal (62), (4), 2010, p. 694. ↵

[33] R. Holland: Alan Paton Speaking the Lintrose Conversations interview with Alan Paton, p. 11. and P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, p. 155. ↵

[34] P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, pp. 155-156. ↵

[35] P. Rule, M. Aitken, and J. van Dyk: Nokukhanya, Mother of Light, pp. 156-157, 160-161. ↵

[36] South African History Online, “Speech by President Mandela at the Funeral of Nokukhanya Luthuli, 22 December 1996, Groutville,” http://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/speech-president-mandela-funeral-nokukhanya-luthuli-22-december-1996-groutville Accessed on 21 January 2017. ↵

[37] R. Suttner: ‘“The Road to Freedom is via the Cross’ ‘Just Means’ in Chief Albert Luthuli's Life,” South African Historical Journal (62), (4), 2010, p. 694. ↵