Introduction

Since independence, English has been Namibia’s only official language. This was a controversial policy and remains contested. This timeline provides some historical background to the role of English in the Namibian public by tracing it within the country’s publication history. Publication history includes texts that were published, the presses that published them and the institutions where writing happened. This timeline focuses on English-language literary publications, including oral sources, plays, novels, novellas, short stories, newsletters and poems, but also includes other important events. Publishing history provides us with insights into the production and dissemination of knowledge and in addition helps us trace overlapping networks through material objects.

When South Africa took over the administration of South West Africa from Germany, it entered a sparse publication environment, where English did not play a role. The earliest printing presses inside the territory were owned and operated by missionaries, namely the Rhenish Mission Society and the Finnish Mission Society, who published religious texts mainly in indigenous languages.[1] The first English-language publications in Namibia were South African government publications during the inter-war period. These were practical guides meant to help settlers adjust to their new environment and publications related to local businesses.[2] It was not until after World War II, when the South African administration left the publishing scene inside Namibia that a greater variety of English-language publications emerged.[3]

TIMELINE

1867

Robert Grendon is born in Ovamboland[4]. He likely went to Augustineum School in Otjimbingwe for two years before moving to South Africa’s Zonnebloem College at age 10 where he received an English education. Grendon started writing in the 1890s.[5] During 1901-1903 he published several poems in English in the Ipepa Lo Hlanga and Ilanga newspapers, under various pseudonyms.[6] He probably also contributed to Abantu Batho’s early publications. In 1914 he published a poem and a letter, the latter of which was published in six parts in Izwe La Kiti, attacking arguments against miscegenation, as well as a poem.[7] His published poems include “Paul Kruger’s Dream”, “Tshaka’s Death”, “Amagunyana's Soliloquy”, “A Tribute to Miss Harriet Colenso”, “What Man's Accomplish'd Ye Can Do”, “Ilanga” and “Press On Ohlange”.[8]

1943

Mvula ya Nangolo was born in northern Namibia.[9] He was a print and radio journalist in Europe and Africa, edited Namibia Today and worked for SWAPO’s Department of Information and Publicity and published two volumes of poetry. He became known as the “Father of Namibian poetry.”[10]

1950

Naro and his Clan: The Lost World of the Bushmen by Fritz Metzger is published.[11] Originally written in German, it was first published in its English translation in 1950 by the South West African Scientific Society, one of three new major publishers established in the post-war publishing boom.[12] The book was written while the author was in an internment camp during WWII. Reflecting back he stated “[I] had more than enough time on my hands in any event…” to put together notes collected about the ‘Bushmen’ during encounters on his tobacco farm.[13]

1955

Karibib, a Rhenish missionary printing press, was established.[14] It published Immanuel, a newsletter printed in Afrikaans, Nama/Damara and Otjiherero.[15]

1959

Omahodhi gaavali by H.D. Namuhuja is published by Finnish Mission Press.[16] This is likely the first non-religious book by a black Namibian to be published.

1959

Allard Lowenstein, Emory Bundy and Sherman Bull, three Americans, undertook an illegal fact-finding mission to Namibia in order to further the cause of Namibian independence.[17] The three smuggled recorded testimony of Namibians that they had collected out of South Africa and played them for the Fourth Committee at the UN.[18] This was perhaps the most extensive collection and use of oral sources in the 20th century before the 1980s.

1960s

Among other consequences, the Van Zyl and Odendaal Commissions resulted in the decline, though not disappearance, of the mission press, one of the only presses that catered to non-white readership and which published writing by non-white people.[19] They also meant that the South West Africa Department of Education, and later the South Africa Department of Bantu Education, took over the publication of textbook.

1960s

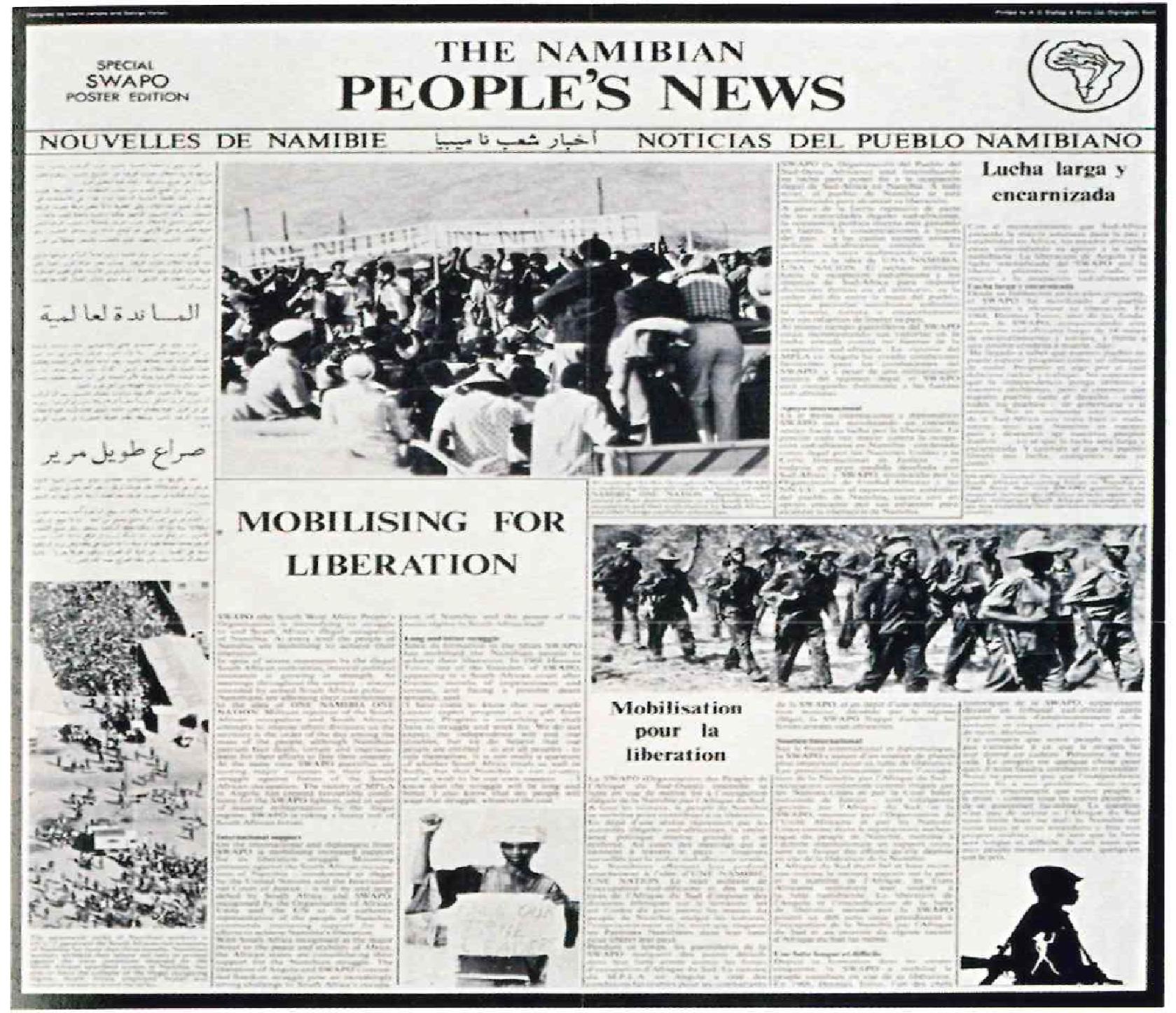

SWAPO began publishing in English the 1960s. Throughout the decade, it irregularly published Solidarity, Namibia Today and SWAPO Information & Comment in English.[20] Namibia Today, SWAPO Information Bulletin and The Combatant and other publications ran more regularly in the 1970s (figure 2). These were propaganda publications. They were also the first time Namibians in exile could publish their views and literature. Namibian poets were published for the first time in these.

Figure 2 “The Namibian People’s News. Nouvelles De Namibie. Noticias Del Pueblo Namibiano. [Arabic]” black-and-white offset. Part of a calendar sheet, April and May 1977[21] Image source

Figure 2 “The Namibian People’s News. Nouvelles De Namibie. Noticias Del Pueblo Namibiano. [Arabic]” black-and-white offset. Part of a calendar sheet, April and May 1977[21] Image source

1960

South West News, a “nationalist newspaper,”[22] was established in March 1960. Written mostly by Namibia’s black intelligentsia who formed the African Publishing Company. This was a fortnightly publication in English, Afrikaans and Otjiherero.[23] The first two editions were printed in South Africa by Prometheus Printers and Publishers. After the Prometheus offices were raided by South African forces, South West News was printed in Windhoek by Windhoek Printing Works. After nine editions, it folded altogether due to financial constraints and because most of its editors went into exile.[24]

1969

The Liberation Support Movement (LSM) was founded. It operated in Canada and America as a Marxist-Leninist support group of national liberation movements in southern Africa and elsewhere.[25] One of the group’s main activities were collecting, editing and publishing autobiographies of people involved in these struggles. This culminated in a series titled “Life Histories from the Revolution”. LSM also conducted and published interviews with liberation struggle leaders. The memoirs of SWAPO members John Ya-Otto and Vinnia Ndadi, originated as LSM publications. LSM also supplied these movements with printing equipment and trained two SWAPO members in print shop skills. The printing equipment was operated from Luanda, Angola.[26]

1973

The printing press at Oniipa was bombed for the first time by the South African army.[27] It was founded and operated by the Finnish Mission Society and had been publishing Omukwetu, an Oshiwambo-language newsletter since 1901. Since the 1970s, the newsletter included critical views of the war in northern Namibia.

1973

Cosmo Pieterse was the only Namibian writer included in Donald E. Herdeck’s encyclopedia-style African Authors: A Companion to Black African Writing 1300-1973.[28] He was born in 1930 in Windhoek. Pieterse’s status as a Namibian author is questioned by Henning Melber, who argues that he left Namibia “without in any direct way being related to the Namibian cause.”[29]

1974

Echoes and Choruses: Ballad of the Cells and Selected Shorter Poems by Cosmo Pieterse was published by Ohio University Press.[30]

1974

Liberation Support Movement published Vinnia Ndadi and Dennis Mercer’s Breaking Contract: The Story Vinnia Ndadi.[31]

1975

English began to be used in parts of Immanuel, the newsletter printed from the Rhenish missionary printing press Karibib.

1976

The first volume of Namibian poetry in English was published. It was Mvula ya Nangolo’s chapbook From Exile.It was self-published in Zambia and included thirteen poems.[32]

1976

The United Nations Institute of Namibia (UNIN) is founded in Zambia. It was perhaps the most influential force on Namibian English-language exile writing and was probably the most elaborate education initiative for Namibians, specifically SWAPO members.[33] UNIN’s goal was to educate Namibians in exile, in preparation for independence. They chose English as their medium of instruction. Between 1976 and 1989, UNIN trained approximately 1427 students. SWAPO’s education institutions in exile, particularly UNIN, were seen as serious rivals to the education available for black students inside Namibia.[34] SWAPO’s education initiatives were aided by textbooks and self-teaching books for exiled youth and adults published by The Namibia Project and SWAPO’s Literacy Program.[35]

1976

South African playwright Frederick Philander moved to Namibia and became involved in theatre-making in the country.

1978

The Windhoek Observer was established.[36] Published in English, this was the only mainstream liberal newspaper.

1979

Frederick Philander’s theatre troupe, the Windhoek Theatre Association, was established. It was composed of three branches: Serpent Players, Windhoek Players and Committed Artists of Namibia, whose members were school-going and unemployed youth, amateur adult actors and semi-professional adult actors, respectively.[37]

1979

Young Namibian Poetry was published.[38] The 22-page volume of black Namibian poetry consisted of poems from members of UNIN’s Creative Writing Club. It was published in Zambia.

1980

Gamsberg Publishers was founded by Herman van Wyk and Hans Viljoen. It initially emphasised African languages and “also laid the foundations for a formal, organized and strong publishing set-up for Namibian books by Namibian authors…”[39] Gamsberg soon joined the ranks of Namibia’s biggest publishers.

1980

The Council of Churches in Namibia (CCN) first published their newsletter, CCN Information, in English.[40] It was printed by the Angelus printing shop and spawned the CCN to create a Communications Unit. Its name later changed to CCN/RRR News and was turned into a supplement of The Namibian. It then became The Messenger, a monthly church magazine.[41]

1980

The South African government opened the Academy of Tertiary Education (ATE), the first university in Namibia. It was open to black students. It was set up to compete with UNIN’s influence and to keep young people in the country.[42]

1980

The printing press at Oniipa was bombed for the second time by the South African army.[43]

1980

Tim Couzens wrote part of his Doctoral thesis about Robert Grendon, in which he quoted (thereby reprinting) at least part of Grendon’s work.[44] 1981 Battlefront Namibia: An Autobiography by John Ya-Ottowas published in America by Lawrence Hill & Company.

1981

UNIN and SWAPO published Toward a language policy for Namibia: English as the official language.[45] This was one of several important policy papers that they co-produced. UNIN publications were treated as development documents and were therefore distributed among elite UN and solidarity networks.[46] By 1990 the UNIN disbanded. Following independence these networks disintegrated. As a result many publications went unsold, never reached a larger market or disappeared altogether.

1981

Jan Knappert published Namibia Land and Peoples, Myths and Fables as part of the Religious Texts Translation Series from a publisher in The Netherlands.[47] The book was described as a collection of oral literature, not history, and included myths, legends, a few proverbs and songs.[48] This project was motivated by the expectation of Namibia’s impending independence, which did not happen until almost a decade later.[49]

1982

It Is No More a Cry, a book of Namibian exile poetry, was published by the Switzerland-based Basler Afrika Bibliographien.[50]

1982

Battlefront Namibia: An Autobiography by John Ya-Otto was republished by Heinemann publishers as part of their African Writers Series (AWS). It was the first Namibian book to be part of AWS. Until 2001, it remained the AWS’s only Namibian publication.

1982

Liberation Support Movement, which supported Namibia’s liberation movement and published biographical interviews with some of its leaders, closed.

1983

Harold Farmer’s 1983 poem “Lost City” was published in Meanjin, an Australian literary magazine.[51] Farmer was born in Windhoek in 1943. A lawyer who attended universities in Zimbabwe, Cape Town and Australia, Farmer lectured in English at the University of Zimbabwe until 1988.[52]

1984, December

The community newspaper, Bricks, was launched by Katutura Residence Action and Khomasdal Burgervereniging. At first this was written entirely in Afrikaans. However, the language gradually shifted until by 1990 the publication was entirely English. The first edition was printed in South Africa by Esquire Press, then by Akasia Printing Works located in Rehoboth, near Windhoek. The Bricks Community Project developed as a result of the newspaper. They had a theatre group as well as activist training.[53]

1984

Namibia’s National Archives established the Archaeia series and began to publish.[54]

1984

Namibian Women, a quarterly magazine published by the SWAPO Women’s Council, was launched.[55]

1984

The Windhoek Observer dismissed one of its senior editors, Gwen Lister, due to government pressure. This was seen as the moment when the publication lost its edge as a mainstream liberal newspaper. The entire staff of The Windhoek Observer resigned in solidarity with Lister.

1985

After being dismissed from The Windhoek Observer due to government pressure, Gwen Lister founded The Namibian with Dave Smuts. Both these English-language newspapers still in existence as of 2016.

1985

The Windhoek Theatre Association founded the Youth Drama Festival which, for over thirty years, remained “arguably the most influential showcase in Namibia.”[56]

1985

Speak Out, a newsletter intended for Katutura residents, was published for the first time by the Katutura Community Centre.[57] Although Speak Out was initially meant to be a monthly publication, their output was infrequent and they eventually folded in 1989.

1985

The Student Voice of Namibia, a newsletter, was published for the first time. It acted as the mouthpiece of the Namibian National Students Organization, the student intelligentsia. First published in English, some Afrikaans was later integrated, before becoming fully English again

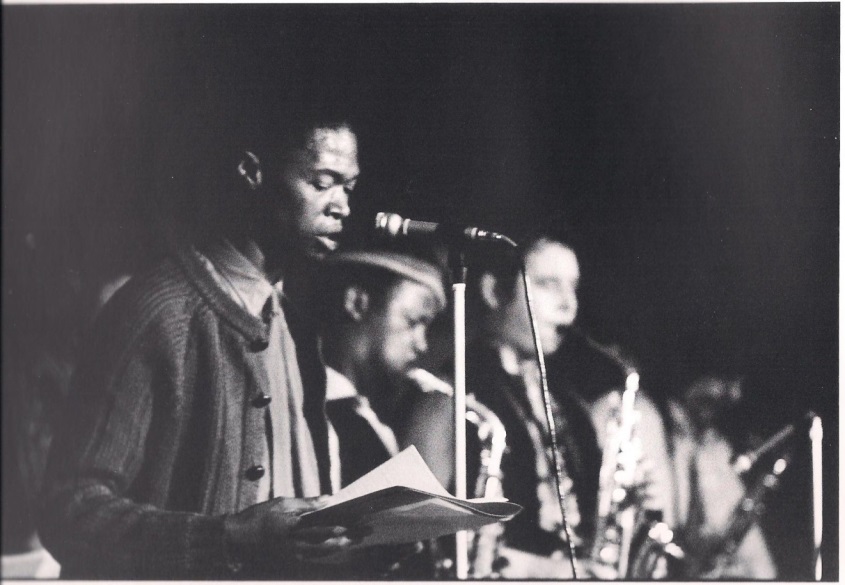

1985

When My Brothers Come Home: Poems from Central and Southern Africa included work from two Namibian poets, Mvula ya Nangolo and Cosmo Pieterse (figure 4).[58]

Figure 4. Cosmo Pieterse performing with Chris McGregore’s Brotherhood of Breath, London, 1972[59] Image source

Figure 4. Cosmo Pieterse performing with Chris McGregore’s Brotherhood of Breath, London, 1972[59] Image source

1985

The Michael Scott Oral Records Project (MSORP) was established. Its aim was to collect, archive and make available oral records of Namibians in order to add dimension to Namibia’s history that had thus far been written mainly by “colonising or evangelising European men.”[60] Between 1985 and 1992, MSORP had been involved in archiving around 70 audiocassettes. A landmark project, this was the first extensive oral history project created for the purposes of preserving stories and histories rather than to serve linguistic, economic, political or religious purposes.[61]

1986

The Michael Scott Oral Records Project (MSORP) publisheda historical epic in The Mbanderu: Their history as told to Theo Sundermeier.

1986

Robert Grendon’s poem “Amagunyana's Soliloquy” was included in the anthology The Paperback of South African English Poetry.

1986

Ndeutala Hishongwa published her novella Marrying Apartheid in Australia, from which it was distributed through solidarity networks. As a post-graduate student she attended the Centre for Comparative and International Studies in Education at La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia. Hishongwa was born in 1952 in Okalili, northwest Namibia. She trained as a nurse and in 1974 joined SWAPO in exile in Zambia. She was sent to Sweden to study on scholarship from the Lutheran World Federation and studied at the University of Stockholm and Växjö University.

1986

“It’s Like Holding the Key To Your Own Jail”: Women in Namibia by Caroline Allison was published.[62] Allison begins each chapter with a contextual description before an extensive quote from a female Namibian informant, some named, some not. Each chapter has several quotes, each with its own descriptive introduction.

1987

The Namibian Worker was launched as an “educational tool” of the 1980s union revival.[63] It included poems by workers.

1988

The Namibian Children’s Book Forum was founded, followed by the Build a Book Collective, which later worked with New Namibia Books.[64]

1988

Through the Flames: Poems from the Namibian Liberation Struggle was published by the Namibia Project (a partnership between the University of Bremen, UNIN and SWAPO’s Department of Education and Culture), in co-operation with Terre des Homes, Zimbabwe Publishing House and Zed Books.[65]

1988

The conference proceedings from ‘Namibia 1884-1984: 100 years of foreign occupation; 100 years of struggle’ was published. UNIN contributed to collecting, editing and printing the book.[66] While most of the papers were non-fiction, it also included some literature. This includes the reprinting of a booklet Five Animal Stories from Namibia, adapted and retold by Michael Hishikushitja, in the article “Adaptation of traditional Namibian stories for a European audience”.[67] The booklet’s original publication information is not given, but it was written for primary schools in England and distributed to a limited number of these.[68] In addition to this, Simon Zhu Mbako has a paper in which he compiles English-language poetry from “original Namibian sources,” Mbako’s own work draws on “stories still told today,” and poems previously published elsewhere.[69] None of the poems are credited with authorship and most are undated. A similar situation arises in Ndopu’s paper “Writing in Namibia”.[70] The non-fiction presentation is followed by two short stories in English by Ndopu which the introduction says are taken from a longer collection, about which no information is given. The paper “Namibian education and culture” by Nghidi Ndilula includes a poem in English by N.U. Ndilula (presumably the same author of the paper).[71] The entire paper, with the poem, was originally published in Action on Namibia, the Namibia Support Committee’s bulletin, in September 1984. Also included is “The struggle for education: a play” by Aili Amutenya, Ruusa Iileka, Ruusa Indongo, Vilkuna Kleophas, Lydia Matti, Albertina Nashandi, Claudia Negumbo, Julia Sheefani, Helen Shikela and Pengeyovali Taneni.[72] The play, put together by female Namibian students in exile in England, was first performed there in 1982. The published version is a transcription from a video-recording of the first performance’s dress rehearsal.

1988

Joseph Diescho’s Born of the Sun was published. Diescho was born in the Kavango region of Namibia in 1955.[73] He is a political analyst, lay preacher and novelist. This book is commonly identified as the first Namibian novel. Diescho wrote the book, with the assistance of Celeste Wallin, while attending Columbia University. It was published in New York by Friendship Press.

1988

Naro and his Clan: The Lost World of the Bushmen by Fritz Metzger was republished in its original German to much acclaim. Between 1988 and 1993, the book went through three editions.

1989

Tell Them of Namibia: Poems from the National Liberation Struggle was published in London by Karia Press.[74] The anthology includes 42 poems by 21 authors. It was compiled, introduced and edited by Simon Zhu Mbako, who also wrote 17 of the poems. Mbako was born near Tsumeb in 1950 and attended Augustineum high school, where he found his first political influences.[75] In 1976 he left Namibia in order to avoid arrest for trying to smuggle diamonds out of a mine and joined SWAPO’s military wing. Between 1977 and 1985, he attended UNIN, went to school in Yugoslavia, worked in Lusaka and went to school in England. When he returned to SWAPO in Africa, they sent him to Lubango, Angola, where he “joined the growing number of educated exiles…suspected of being spies...”[76] Unlike others at Lubango, he was not tortured, but did fall ill. He recovered by 1989 and returned to Namibia.

1989

In Search of Freedom: The Andreas Shipanga Story as told to Sue Armstrong, by Andreas Shipanga and Sue Armstrong, was published in Gibraltar by Ashanti Publishing.[77] Shipanga was at the centre of SWAPO’s internment of their own members. In Search of Freedom is Shipanga’s memoirs from his childhood to the time following his release from jail.

1989

The Penguin Book of Southern African Verse is published. It included Nguno Wakolele’s “Southern Africa”.[78] Wakolele was born in Namibia and went into exile to Zambia in 1982 where he was a UNIN student.[79]“Southern Africa” was first published in Young Namibian Poetry (1979). Wakolele went on to occupy important government roles after Namibia’s independence.[80] Also included was Harold Farmer’s 1983 poem “Lost City”.

1989

The National Archives of Namibia republished The Hendrik Witbooi Papers from Windhoek. Long considered a national hero, Witbooi was a Nama leader in the late 19th and early 20th century who led a rebellion against the Germans.[81] The diary he kept from 1884 to 1893 was written in Dutch and originally published in 1929 as Die Dagboek van Hendrik Witbooi, Kaptein von Witbooi-Hottentotte, 1884-1905.

1989

Vinnia Ndadi and Dennis Mercer’s Breaking Contract: The Story Vinnia Ndadi was republished by the International Defence and Aid Fund for Southern Africa (IDAF) Publications in London. It was included in IDAF’s reprint series in which they took publications from “an earlier period in the history of the [anti-apartheid and minority rule] struggle” that seemed relevant at the time.[82]

1989

Frederick Philander’s play Katutura ’59, was produced.

1989, April

Sister R Namibia, a magazine, launched in April. It was and remains dedicated to gender issues.[83] It was published in Afrikaans and English and was originally not printed but typed and photocopied.

1989, July

Based on the publication Sister Namibia, Sister Collective was founded as a women’s organization in July 1989. There was initial controversy over the publication, as it was founded by white and coloured women and seen as a pastime for middle-class women.

Early 1990s

The Namibian Book Development Council was created as a network for anyone linked to book production.

1990

Longman Namibia became an independent publisher, having previously been a part of Maskew Miller Longman. They published in English, as well as other languages.

1990

New Namibia Books, a publisher which published Namibian fiction, was established. They published in English, as well as other languages.

1990

Gamsberg became part of Macmillan UK.[84] They published in English, as well as other languages.

1990

The Scientific Society increased its English-language publications.

1990

SWAPO member Helao Shityuwete published his memoirs Never Follow the Wolf: The Autobiography of a Namibian Freedom Fighter.[85] Shityuwete was born in southern Angola and received a missionary education in Namibia.[86] He went into exile in Tanzania, joined Namibia’s armed struggle, was caught and charged under the Terrorism Act and spent 16 years on Robben Island. His book was published in London by Kliptown Books.

1990

The Two Thousand Days of Haimbodi Ya Haufiku by Helmut Angulawas published in Windhoek by Gamsberg Macmillan. The author was a Member of Parliament and a Deputy Minister when the book was published.[87] He wrote the novel in English while based in Havana as SWAPO’s Chief Representative for the Caribbean.[88] It was originally published from Bremen in German in 1986. The Centre for African Studies/Namibian Project at the University of Bremen had helped him translate and publish the German publication.[89]

1990

Sister Namibia became a monthly printed magazine. Black women begin to join the SISTER Collective, a women’s organization associated with the publication.

1990

UNIN disbanded.

1990

Gamsberg Publishers joined Macmillan UK publishers and became Gamsberg Macmillan. It became a major English-language publisher in Namibia.[90]

1990

Harold Farmer published a book of poetry, Absence of Elephants, in Zimbabwe by College Press.

1990

Frederick Philander’s 1989 play The Curse, previously Katutura ’59, was published by Skotaville Publishers in Braamfontein, making him one of the few black playwrights to be published in southern Africa at the time.[91] 1991 Namibia’s National Library established its own ISBN agency instead of relying on Pretoria’s classification system.[92]

1991

The Association of Commercial Publishers of Namibia was founded by six Namibian publishers.[93] It later changed its name to the Association of Namibian Publishers and was a founding member of the continent-wide African Publishers Network in 1992.

1991

The Namibia Writers’ Association was established.[94] It underwent a constitutional change in 1992. Thereafter it was known as the Namibian National Writers’ Union (NANAWU), which “organizes writers countrywide to protect their rights and to promote writing skills.”[95]

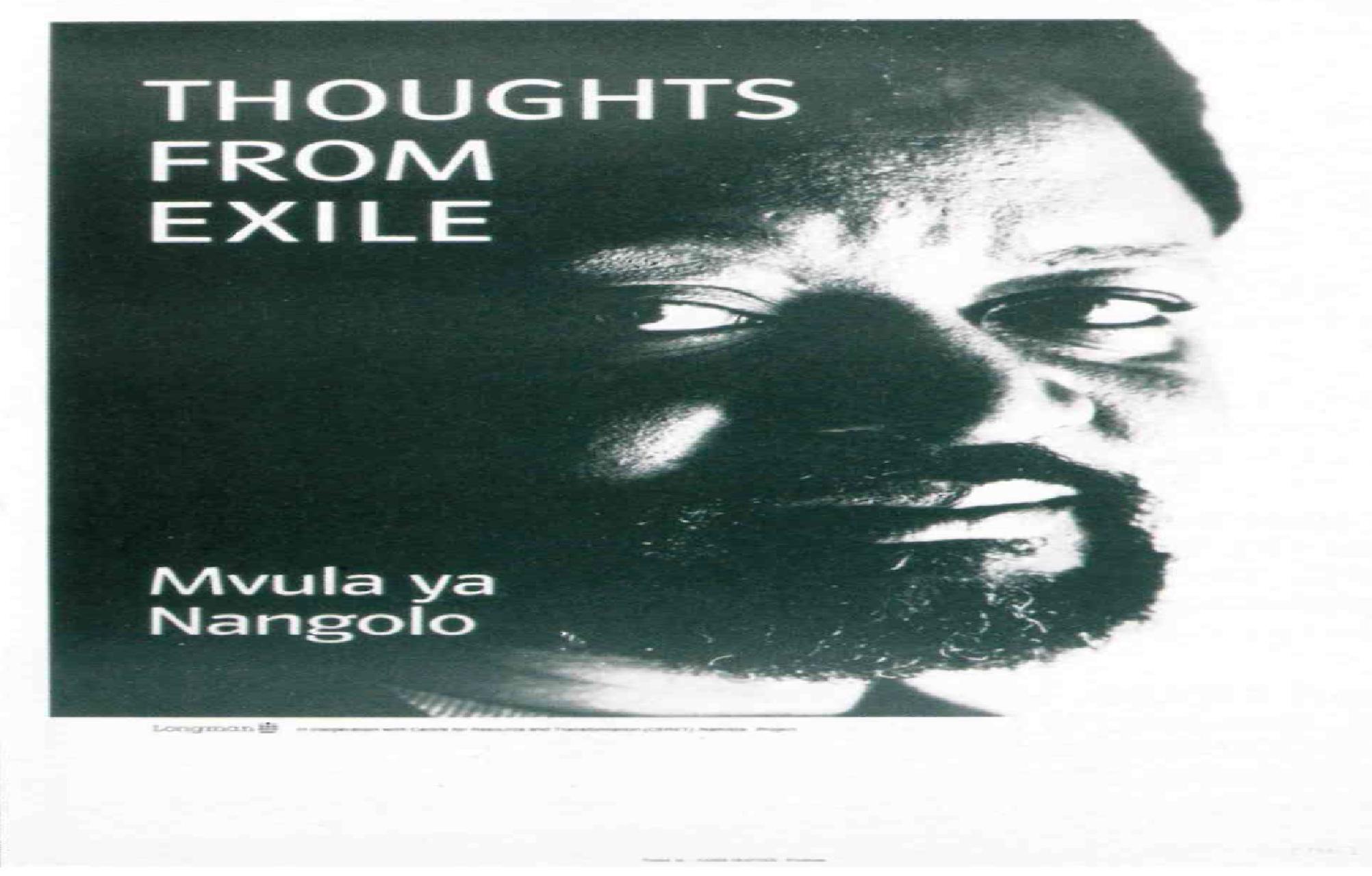

1991

Mvula ya Nangolo published Thoughts from Exile, his second collection of English poetry, from Windhoek (figure 3).[96]

Figure 3 “Thoughts From Exile. Mvula ya Nangolo.” 1990, Namibia / English, 635x430, Longman in cooperation with Centre for Resource and Transformation/ Namibia Project. Namib Graphics, Windhoek/ black-and-white offset.[97] Image source

Figure 3 “Thoughts From Exile. Mvula ya Nangolo.” 1990, Namibia / English, 635x430, Longman in cooperation with Centre for Resource and Transformation/ Namibia Project. Namib Graphics, Windhoek/ black-and-white offset.[97] Image source

1991

Dorian Haarhoff reprints excerpts from Robert Grendon’s “Amagunyana’s Soliloquy” and “Paul Kruger’s Dream” and argues that Grendon should be read as a Namibian in exile.

1992

The Michael Scott Oral Records Project (MSORP) publishedWarriors Leaders Sages and Outcasts in the Namibian Past: narratives collected from Herero sources for the MSORP project 1985-1986.

1993

The German publication of Naro and his Clan: The Lost World of the Bushmen by Fritz Metzgerwon the Namibian Children’s Book Forum’s German prose medal.[98] As a result, it was re-translated into English and re-published in the same year.

1993

The Council of Churches in Namibia’s monthly church magazine, The Messenger, folds.

1993

Joseph Diescho published his second novel, Troubled Waters.

1994

Namibia held the First Namibian Book Festival.

1995

A second revised English edition of The Hendrik Witbooi Papers was published.

1996

A second revised and enlarged edition of The Hendrik Witbooi Papers was published. It included Witbooi’s journals and letters newly found in the Ubersee-Museum in Bremen.[99]

2000

Meekulu’s Children is a novel written by Kaleni Hiyalwa, published in 2000. Hiyalwa was born in Onhamunhama, a village in the Ohangwena region of northern Namibia.[100] She spent many years in exile and was educated in Zambia and Cameroon. Hiyalwa taught at the Namibia Education Centre at the Kwanza Sul settlement, Angola. She obtained a diploma in Journalism from the Ghana Institute of Journalism and has worked in journalism, health and gender sectors in Ghana and Namibia. Meekulu’s Children was her first novel. She has also written and published short stories and poems.[101]

2001

The Purple Violet of Oshaantu was published by Heinemann’s African Writers Series, the second book and only novel from Namibia which the famed series has published. It was written by Neshani Andreas who was born and raised in Walvis Bay, central Namibia, in 1964.[102] Andreas attended Ongwediva Training College and, after working in a clothing factory, taught English, History and Business Economics in a village in northern Namibia for four years. She moved to Windhoek in 1994 where she attended the University of Namibia and joined the Peace Corps, taking up the appointment of Associate Director for four years. A Peace Corps volunteer first encouraged her writing and Jane Katjavivi, a publisher, later passed on the manuscript of The Purple Violet of Oshaantu to Heinemann. At the time of her death, she was a Programme Officer at the Forum of African Women Educationalists in Namibia and is said to have completed a second manuscript, as yet unpublished.

2004

It Is No More a Cry: Namibian Poetry in Exile and Essays on Literature in Resistance and Nation Building edited by Henning Melber was republished in 2004 with additional essays by the editor. The essays had originally been published elsewhere in 1988, 1990 and 1994.

Endnotes

[1] Peter Reiner, Jane Katjavivi, and Werner Hillebrecht, Books in Namibia: Past Trends and Future Prospects (Windhoek: Association of Namibian Publishers, 1994), 3. ↵

[2] Ibid., 8. ↵

[3] Ibid., 9. ↵

[4] Tim Couzens, “Robert Grendon: Irish Traders, Cricket Scores and Paul Kruger’s Dreams,” English in Africa 15, no. 2 (October 1, 1988): 63, doi:10.2307/40238624. ↵

[5] Ibid., 71. ↵

[6] Ibid., 77. ↵

[7] Ibid., 81, 84. ↵

[8] Ibid., 49–53, 53, 72–75, 76, 77, 78–80. ↵

[9] Frank Mkalawile Chipasula, ed., When My Brothers Come Home: Poems from Central and Southern Africa, 1st ed, Wesleyan Poetry (Middletown, Conn.; Scranton, Pa: Wesleyan University Press ; Distributed by Harper & Row, 1985), 145. ↵

[10] Sarala Krishnamurthy, “Re: Namibian Literature Research,” April 2, 2013. ↵

[11] Fritz Metzger, Naro and His Clan: The Lost World of the Bushmen, trans. P Reiner, 2nd ed. (Windhoek: Kuiseb-Verlag, 1993). ↵

[12] Reiner, Katjavivi, and Hillebrecht, Books in Namibia: Past Trends and Future Prospects, 9. ↵

[13] Metzger, Naro and His Clan: The Lost World of the Bushmen, 5. ↵

[14] William Heuva, Media and Resistance Politics: The Alternative Press in Namibia, 1960-1990 (Basel: P. Schlettwein Pub., 2001), 28. ↵

[15] Ibid., 29. ↵

[16] Reiner, Katjavivi, and Hillebrecht, Books in Namibia: Past Trends and Future Prospects, 12. ↵

[17] Allard Lowenstein, Brutal Mandate: A Journey to South West Africa (London, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1962), v. ↵

[18] Ibid., vi. ↵

[19] Reiner, Katjavivi, and Hillebrecht, Books in Namibia: Past Trends and Future Prospects, 10. ↵

[20] Ibid., 15. ↵

[21] Giorgio Miescher and Dag Henrichsen, African Posters: A Catalogue of the Poster Collection in the Basler Afrika Bibliographien, trans. Anne Blonstein (Basel: Basler Afrika Bibliographien, 2004), 22. ↵

[22] Heuva, Media and Resistance Politics, 15. ↵

[23] Ibid., 20–23. ↵

[24] Maria Mboono Nghidinwa, Women Journalists in Namibia’s Liberation Struggle 1985-1990 (Basel: Basler Afrika Bibliographien, 2008), 26, https://books.google.co.za/books?id=o1t9T3VNjRYC&pg=PA26&lpg=PA26&dq=Prometheus+Printers+Namibia&source=bl&ots=qrUQgG3rjt&sig=3pyL1-5ZNoYTIu9hHTmf2KmHr2M&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj0uuLh3crNAhUBBsAKHRM7D1wQ6AEIHDAA#v=onepage&q=Prometheus%20Printers%20Namibia&f=false. ↵

[25] “Aluka - Liberation Support Movement Pamphlet Collection,” paras. 1, 3, accessed January 9, 2013, http://www.aluka.org/action/showCompilationPage?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.COMPILATION.COLLECTION-MAJOR.LSMPC&. ↵

[26] Netumbo Nandi, Mathilda Amoono, and Carole Collins, “This Is the Time: Interview with Two Namibian Women” (Chicago Committee for African Liberation, August 26, 1977), 27, http://kora.matrix.msu.edu/files/50/304/32-130-59B-84-african_activist_archive-a0b3h5-a_12419.pdf. ↵

[27] Giorgio Miescher, Lorena Rizzo, and Jeremy Silvester, eds., Posters in Action: Visuality in the Making of an African Nation (Basler Afrika Bibliographien, 2009), 23, https://books.google.co.za/books?id=m7xp9XE-zX8C&pg=PA18&lpg=PA18&dq=rhenish+mission+press,+namibia&source=bl&ots=XSgq6tGK9A&sig=sbJ2f7U01ypNSxIgLl2uuZHOMj4&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjl5IqD76TNAhVhB8AKHRMbDrAQ6AEINTAF#v=onepage&q=rhenish%20mission%20press%2C%20namibia&f=false. ↵

[28] Donald E Herdeck, African Authors : A Companion to Black African Writing, 1300-1973. (Washington: Black Orpheus Press, 1973), 344. ↵

[29] Henning Melber, It Is No More a Cry : Namibian Poetry in Exile and Essays on Literature in Resistance and Nation Building (Basel: Basler Afrika Bibliographien, Namibia Resource Centre & Southern Africa Library, Switzerland, 2004), 83. ↵

[30] Herdeck, African Authors, 344; Cosmo Pieterse, Echo and Choruses Ballad of the Cells and Selected Shorter Poems (Ohio Univ Pr (Trd), 1974). ↵

[31] John Ya-Otto, Battlefront Namibia: An Autobiography (Westport, Ct: Lawrence Hill & Co, 1981); Dennis Mercer, Breaking Contract : The Story of Vinnia Ndadi (Richmond, D.C: LSM Information Center, 1974); Dorian Haarhoff, The Wild South-West: Frontier Myths and Metaphors in Literature Set in Namibia, 1760-1988 (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1991), 224–25; Michael Chapman, “Making a Literature: The Case of Namibia,” English in Africa 22, no. 2 (October 1, 1995): 23, doi:10.2307/40238808. ↵

[32] Helen Vale, “Namibian Poetry in English 1976-2006: Between Yesterday and Tomorrow - Unearthing the Past, Critiquing the Present and Envisioning the Future,” Nawa Journal of Language and Communication 2, no. 2 (December 2008): 37. ↵

[33] Brian Joseph White, Relevance, Rhetoric and Reality: National Development at the University of Namibia, Occasional Papers 73 (Centre of African Studies, Edinburgh University, 1998), 32. ↵

[34] Henning Melber, “New Tendencies of an Old System: Neo-Colonial Adjustments Within Namibia’s System of Formal Education,” in Namibia 1884-1984 : Readings on Namibia’s History and Society., ed. Brian Wood (Namibia 1884-1984: 100 years of foreign occupation; 100 years of struggle, London 10-13 September, 1984, organized by the Namibia Support Committee in co-operation with the SWAPO Department of Information and Publicity, London, Lusaka: Namibia Support Committee in cooperation with United Nations Institute for Namibia, 1988), 411. ↵

[35] Reiner, Katjavivi, and Hillebrecht, Books in Namibia: Past Trends and Future Prospects, 19. ↵

[36] Heuva, Media and Resistance Politics, 55. ↵

[37] Dennis Schauffer, “Frederick B. Philander—Maverick Playwright of Namibia,” South African Theatre Journal 23, no. 1 (2009): 139, doi:10.1080/10137548.2009.9687906. ↵/p>

[38] Reiner, Katjavivi, and Hillebrecht, Books in Namibia: Past Trends and Future Prospects, 16. ↵

[39] Ibid., 13. ↵

[40] Heuva, Media and Resistance Politics, 32. ↵

[41] Reiner, Katjavivi, and Hillebrecht, Books in Namibia: Past Trends and Future Prospects, 19. ↵

[42] White, Relevance, Rhetoric and Reality: National Development at the University of Namibia, 32, 33. ↵

[43] Miescher, Rizzo, and Silvester, Posters in Action, 23. ↵

[44] Haarhoff, The Wild South-West, 114, 244. ↵

[45] Jenna Frydman, “A Critical Analysis of Namibia’s English-Only Language Policy,” in Selected Proceedings of the 40th Annual Conference on African Linguistics (40th Annual Conference on African Linguistics: African Languages and Linguistics Today, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, 2011), 182, http://www.lingref.com/cpp/acal/40/paper2574.pdf. ↵

[46] Reiner, Katjavivi, and Hillebrecht, Books in Namibia: Past Trends and Future Prospects, 18–19. ↵

[47] Jan Knappert, Namibia: Land and Peoples : Myths and Fables, vol. 11, Religious Texts Translation Series from NISABA (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1981). ↵

[48] Ibid., 11:7–8. ↵

[49] Ibid., 11:unpaginated. ↵

[50] Stephen Gray, ed., Penguin Book of Southern African Verse (London: Penguin Books Ltd, 1989), 392. ↵

[51] Ibid., 298, 379. ↵

[52] Dan Wylie, “Unconscious Nobility: The Animal Poetry of Harold Farmer,” English in Africa 34, no. 2 (October 1, 2007): 34, doi:10.2307/40239080. ↵

[53] Heuva, Media and Resistance Politics, 42. ↵

[54] Reiner, Katjavivi, and Hillebrecht, Books in Namibia: Past Trends and Future Prospects, 19. ↵

[55] William Heuva, “Voices in the Liberation Struggle: Discourse and Ideology in the SWAPO Exile Media,” in Re-Examining Liberation in Namibia: Political Culture Since Independence, ed. Henning Melber (Stockholm: Nordic Africa Institute, 2004), 27. ↵

[56] Terence Zeeman, “Confronting the Mask: Some Contemporary Namibian Contexts of Protest,” in African Theatre: Southern Africa, ed. David Kerr, 1st Africa World Press ed, African Theatre 4 (Oxford : Trenton, NJ : Cape Town: James Currey ; Africa World Press ; David Philip, 2004), 24. ↵

[57] Heuva, Media and Resistance Politics, 51. ↵

[58] Chipasula, When My Brothers Come Home, 145–53. ↵

[59] George Hallett, Portraits of African Writers (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 2006). ↵

[60] Annemarie Heywood, Brigitte Lau, and Rajmund Ohly, eds., Warriors, Leaders, Sages, and Outcasts in the Namibian Past: Narratives Collected from Herero Sources for the Michael Scott Oral Records Project (MSORP) 1985-6 (Windhoek: MSORP, 1992), unpaginated. ↵

[61] Haarhoff, The Wild South-West, 85. ↵

[62] Caroline Allison, It’s like Holding the Key to Your Own Jail: Women in Namibia (Geneva: World Council of Churches, 1986). ↵

[63] Heuva, Media and Resistance Politics, 51. ↵

[64] Reiner, Katjavivi, and Hillebrecht, Books in Namibia: Past Trends and Future Prospects, 26. ↵

[65] Ibid., 16, 19. ↵

[66] Hage Geingob, “Foreword,” in Namibia 1884-1984 : Readings on Namibia’s History and Society., ed. Brian Wood (Namibia 1884-1984: 100 years of foreign occupation; 100 years of struggle, London 10-13 September, 1984, organized by the Namibia Support Committee in co-operation with the SWAPO Department of Information and Publicity, London, Lusaka: Namibia Support Committee in cooperation with United Nations Institute for Namibia, 1988), xiii. ↵

[67] Michael Hishikushitja, “Adaptation of Traditional Namibian Stories for a European Audience,” in Namibia 1884-1984 : Readings on Namibia’s History and Society., ed. Brian Wood (Namibia 1884-1984: 100 years of foreign occupation; 100 years of struggle, London 10-13 September, 1984, organized by the Namibia Support Committee in co-operation with the SWAPO Department of Information and Publicity, London, Lusaka: Namibia Support Committee in cooperation with United Nations Institute for Namibia, 1988), 447–57. ↵

68] Ibid., 448. ↵

[69] Simon Zhu Mbako, “The Namib Paradise: Poems from Namibia,” in Namibia 1884-1984 : Readings on Namibia’s History and Society., ed. Brian Wood (Namibia 1884-1984: 100 years of foreign occupation; 100 years of struggle, London 10-13 September, 1984, organized by the Namibia Support Committee in co-operation with the SWAPO Department of Information and Publicity, London, Lusaka: Namibia Support Committee in cooperation with United Nations Institute for Namibia, 1988), 458. ↵

[70] Edward Imasiku Ndopu, “Writing in Namibia,” in Namibia 1884-1984 : Readings on Namibia’s History and Society., ed. Brian Wood (Namibia 1884-1984: 100 years of foreign occupation; 100 years of struggle, London 10-13 September, 1984, organized by the Namibia Support Committee in co-operation with the SWAPO Department of Information and Publicity, London, Lusaka: Namibia Support Committee in cooperation with United Nations Institute for Namibia, 1988), 467–72. ↵

[71] Nghidi Ndilula, “Namibian Education and Culture,” in Namibia 1884-1984: Readings on Namibia’s History and Society Selected Papers and Proceedings of the International Conference on “Namibia 1884-1984: 100 Years of Foreign Occupation; 100 Years of Struggle,” London 10-13 September 1984, Organized by the Namibia Support Committee in Co-Operation with the SWAPO Department of Information and Publicity. (Namibia 1884-1984: 100 years of foreign occupation; 100 years of struggle, London, Lusaka: Namibian Support Committee in cooperation with United Nations Institute for Namibia, 1984), 396–97. ↵

[72] Aili Amutenya et al., “The Struggle for Education: A Play,” in Namibia 1884-1984 : Readings on Namibia’s History and Society., ed. B Wood (Namibia 1884-1984: 100 years of foreign occupation; 100 years of struggle, London 10-13 September, 1984, organized by the Namibia Support Committee in co-operation with the SWAPO Department of Information and Publicity, London, Lusaka: Namibia Support Committee in cooperation with United Nations Institute for Namibia, 1988), 431–46. ↵

[73] NID - Namibia Institute For Democracy, “Diescho, Joseph (Joe) - Political Commentator,” Who’s Who, 2007, http://www.nid.org.na/view_book_entry.php? ↵

[74] Simon Zhu Mbako, ed., Tell Them of Namibia: Poems from the National Liberation Struggle (London: Karia Press, 1989). ↵

[75] Colin Leys and Susan Brown, eds., Histories of Namibia: Living through the Liberation Struggle : Life Histories Told to Colin Leys and Susan Brown (London: Merlin Press, 2005), 16. ↵

[76] Ibid., 24. ↵

[77] Andreas Shipanga and Sue Armstrong, In Search of Freedom: The Andreas Shipanga Story as Told to Sue Armstrong (Gibraltar: Ashanti Publishing, 1989). ↵

[78] Gray, Penguin Book of Southern African Verse, 361–62. ↵

[79] bid., 392. ↵

[80] Zeeman, “Confronting the Mask: Some Contemporary Namibian Contexts of Protest,” 24. ↵

[81] Chapman, “Making a Literature,” 22 ↵

[82] Mercer, Breaking Contract, sec. publication page, unpaginated. ↵

[83] Heuva, Media and Resistance Politics, 45–46. ↵

[84] Reiner, Katjavivi, and Hillebrecht, Books in Namibia: Past Trends and Future Prospects, 21–22. ↵

[85] Helao Shityuwete, Never Follow the Wolf: The Autobiography of a Namibian Freedom Fighter (London: Kliptown Books, 1990). ↵

[86] Ibid., Back cover. ↵

[87] Helmut Pau Kangulohi Angula, The Two Thousand Days of Haimbodi Ya Haufiku (Windhoek: Gamsberg Macmillan, 1990), 126 ↵

[88] Melber, It Is No More a Cry, 76. ↵

[89] Angula, The Two Thousand Days of Haimbodi Ya Haufiku, 6. ↵

[90] Reiner, Katjavivi, and Hillebrecht, Books in Namibia: Past Trends and Future Prospects, 22. ↵

[91] Schauffer, “Frederick B. Philander—Maverick Playwright of Namibia,” 139; Frederick Philander, The Curse: A Four-Act Play on the Namibian Struggle (Skotaville Publishers, 1990). ↵

[92] Reiner, Katjavivi, and Hillebrecht, Books in Namibia: Past Trends and Future Prospects, 32. ↵

[93] Ibid., 23. ↵

[94] Abed Shiimi ya Shiimi, The Most Successful African Businessman in Namibia: The Life Story of Frans Aupa Indongo, trans. Usko S. Shivute (Windhoek: Gamsberg Macmillan Publishers, 2007), Back cover. ↵

[95] United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization | Culture, “World Observatory on the Social Status of the Artist: Literature - Networks and Partners,” Diversity of Cultural Expressions, accessed December 26, 2012, http://portal.unesco.org/culture/en/ev.php-URL_ID=33480&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html. ↵

[96] Miescher and Henrichsen, African Posters, 23. ↵

[97] Ibid., 22. ↵

[98] Metzger, Naro and His Clan: The Lost World of the Bushmen, Back Cover. ↵

[99] Hendrik Witbooi, The Hendrik Witbooi Papers: Second Enlarged Edition, trans. Annemarie Heywood and Eben Maasdorp, 2nd ed. (Windhoek: National Archives of Namibia, 1996), xxviii. ↵

[100] Kaleni Hiyalwa, Meekulu’s Children (Windhoek: New Namibia Books, 2000), Back cover. ↵

101] Bettina Weiss, ed., “Transition, Trauma, and Triumph: Contemporary Namibian Women’s Literature.,” in The End of Unheard Narratives: Contemporary Perspectives on Southern African Literatures (Heidelberg: kalliope paperbacks, 2004), 167. ↵

[102] Shampapi Shiremo, “Namibia: Neshani Andreas - A Gallant Local Author (1964-2011),” New Era, September 23, 2011, para. 5, http://allafrica.com/stories/201109230326.html. ↵