KWANOBUHLE TIMBER HOUSING: A CASE STUDY

PREAMBLE

The activity of building in an urban area, whether it be a simple garden wall or a multi-storey office block, is subject to a variety of legal requirements. Some are statutory and imposed by external bodies such as municipalities, trade unions and central government. Others are contractual and may have been incorporated, by common consent, into a civil agreement between client and builder. Professionals associated with the building industry, such as architects, engineers and quantity surveyors, have to be familiar with building law and are given specific courses in it as part of their academic training. Yet, in spite of this specialized background, many of them will testify that building is not an area for the weak-kneed or faint-hearted to dabble in. Indeed many a lay person who has ventured into this field has reaped a bitter harvest, and tales of bankruptcy, rogue builders and incompetent work are legion. Given the fact that most families will build only once during the course of a lifetime, it appears singularly unfair that their future happiness should ride the roulette wheel of a builder's competence or honesty. This picture is further complicated by the fact that many small contractors are guided by the maxim of "have bakkie, will build", relying in most cases upon the support of a casual and fluctuating labour force. In some instances the experience of building farm structures appears to be sufficient motivation for a career in the industry.

Until recently popular perception saw this problem as being the concern of a relatively small, largely white, middle class group. Going on the assumption that if people could afford to build, they could also afford to litigate, few members of the general public took undue notice of this issue. However, since the early 1980s, when the Government decided to privatise its extensive housing backlog and make it the concern of the building industry, this has also become a problem for southern African society as a whole. Given its peculiar racial and political make-up, it will be seen that a question which previously hinged upon the honesty of an individual builder has now gained potentially explosive undertones, centering upon claims of capitalist and white class exploitation of a voteless black proletariat.

The truth of the matter is that the South African community at large has long gone unprotected from the exploitative practices of a small group of unscrupulous individuals. Working outside the controls of established frameworks, such as BIFSA and the Master Builder's Association, these people have given the building industry an image it scarcely deserves. The well-to-do have been able to purchase for themselves a measure of protection from malpractice through the professional services of an architect or a quantity surveyor. The less affluent have had recourse to no such assistance and it is they who are now bearing the brunt of doubtful business practices. The low-cost housing market has acted as a magnet for a plethora of building firms who have discovered that humanitarian concerns are synonymous with high financial returns. Many of them are established literally overnight and enter into contracts they have no hope, or even intention, of fulfilling. They maximise their profits and, more often than not, close down one step ahead of the court messenger.

A major feature of housing abuse in this country also lies in the experimental nature of many projects. In my experience most complaints received about the technical and economic performance of dwellings relates to the innovative nature of their building methods. These have often been devised in a genuine attempt to meet this country's urgent housing needs. However many such experiments fail either because of technical breakdowns or, more importantly, because the end product does not meet the consumer's social expectations. Whatever the case we should question whether South Africa's poorer communities ought to bear the financial brunt of such experimentation when they, after all, are the ones least able to afford it.

As things stand at the moment there is little point in looking to either building societies, municipalities or central government for relief in this matter. If anything their involvement has made matters worse. For example, when the Government privatised low cost housing, it seemingly also privatised corruption. Before that time prospective homeowners and tenderers for work in black suburbs had to contend with the malpractices of a small group of corrupt officials. The bribe was usually small and was only paid once. Nowadays this malaise appears to have spread to all levels of the housing industry and hardly a week goes past without allegations of corruption being made to me against some member of the housing fraternity, be it a municipal clerk, a building society employee or a building firm. Even the professionals - planners, lawyers and land surveyors - have not escaped this taint. Consultation with colleagues in the field has revealed that a similar situation also pertains in other urban centres in South Africa.

This article deals with an investigation conducted into a small timber housing project in the Eastern Cape, and the problems and abuses which were exposed as a result. In the process it also sets out to debate two major questions. In the first instance, and given the abuses that the system of providing dwellings on an entrepreneurial basis is open to, has "experimental housing" not become just another way of building "inferior housing"? As such is it not then a promulgation of the same inequalities which existed before under the implementation of a "grand apartheid" infrastructure? Secondly, should some kind of control not be instituted to protect the South African public at large from the depredations of unscrupulous individuals - persons who, working under the guise of legitimate building activity, deliberately set out to exploit the weaknesses inherent in our legal system for the purpose of enriching themselves? Should such activities not be criminalised?

The building industry's obvious failure to bring even the most flagrant of offenders to book could have widespread repercussions. Considering the explosive and highly political implications of homelessness, many experts in the field are now advocating a return to our previous system of state-controlled housing. This would be a drastic step and I personally am not entirely convinced that it is the correct one to take. The mechanics of state capitalism, be it motivated by conservative or liberal ideals, have not proved enough, in the past, to ensure social justice for the poorer sectors of our society. However, if the free enterprise system is shown to be inadequate in resolving the moral aspects of this issue, then the government may well be forced to take regulative measures in order to defuse a potentially destructive situation. Perhaps this article signals the beginning of a debate upon this point.

The reader is advised that, for obvious reasons, the names of all parties involved have been fictionalised, although the details of the case study itself are correct.

INTRODUCTION: HISTORY OF THE PROJECT

In about August 1987 Mr Smith, a motor vehicle worker employed in Uitenhage, approached a Mr Bricklaaier, a self-employed builder, with the objective of commissioning the construction of a new residence for himself in the Uitenhage suburb of KwaNobuhle. Bricklaaier was known by Smith to have been allocated a number of stands in this suburb by the KwaNobuhle residential authority for the purpose of housing development.

Smith's actions were given the support of his employers who were prepared to finance his efforts at housing up to a maximum of R19,500 by placing 20% of this amount with a Building Society as a matching investment, thereby assuring Smith of the minimum legal deposit for his bond. As a result a letter signed by the employer's Housing Officer, giving details of Smith's work number, salary and housing amount qualified for, was given to him.

With this budget in mind Smith contacted Bricklaaier who referred him to a dwelling his firm had recently completed in KwaNobuhle as an example of his work. This building appeared to be satisfactory to Smith who agreed to the construction of a similar structure but of smaller dimensions and with a flat roof. A drawing to this effect was shown to Smith by Bricklaaier who gave him a verbal quotation of R16,500 for the work.

Smith asked to be given copies of the plans and a specification for the building. Bricklaaier refused this until such a time as Smith had signed the necessary papers with the Building Society in order to initiate the house bond process. It was verbally agreed between the two men however that this house should be substantially the same as that previously viewed in KwaNobuhle, in that:

- it would have three bedrooms, a lounge, a kitchen and separate bathroom and WC.

- it would be flat-roofed and guttered.

- it would be carpeted throughout, barring the kitchen, bathroom and WC areas which would be lino-tiled.

- it would be electrified and provided with a hot water geyser.

- it would have a cupboard in the master bedroom.

- it would have a grocery cupboard in the kitchen.

- In addition to the above it was also agreed that the property would be fenced off.

At this point Smith handed over the letter of accreditation from his employer's Housing Officer to Bricklaaier who presented it at the Uitenhage branch of the Building Society and initiated the bond application process on Smith's behalf. Smith was then asked to visit the offices of a firm of Attorneys in Uitenhage, to finalise his bond application papers. There he discovered that the bond being granted to him was to the sum of R19,500. When he questioned this fact Smith claims that the attorney handling the transaction, told him that he was entitled to ask the builder for a refund of the R3,000 excess over the previously agreed contract price of R16,500.

When this particular point was queried with the Building Society on 28 October 1987, the current manager of their Uitenhage branch stated it to be unlikely, and probably incorrect, as building societies were prevented by law from advancing bonds for new housing in excess of the builder's contract sum. Subsequent events seem to indicate that Bricklaaier, having an open hand in this matter, did not make the bond application according to his previously agreed quotation to the client, but rather was guided by the upward limit of Smith's housing subsidy.

It was at this point that Smith made a crucial mistake. He signed his bond application papers, which he then returned to Bricklaaier in order to collect copies of the drawings as promised. Bricklaaier once again refused to hand them over, but referred Smith to the house previously viewed in KwaNobuhle, stating that to be his specification and guideline for construction. Two further requests to the same effect by Smith met with a similar response.

In October 1986 Smith was informed by Bricklaaier that his residence was now completed and he could move in. At no stage did Smith see or sign a contract, specification or architectural drawing with Bricklaaier. He also claims that he was never asked to sign a financial release form by the Building Society who, nonetheless, paid a sum of R19,500 to Bricklaaier for this work. At no stage also did the Building Society request of Smith to see his drawings, specifications or contracts nor did they request proof of him that such drawings had been approved by the appropriate urban authority.

Owing to political and social conditions current in this country at that time, which are common currency and therefore need not be enlarged upon here, Smith accepted delivery of the house and, despite serious reservations, moved in during the month of November. It was not long before a number of major flaws inherent in the construction of the dwelling became evident to him and his family. These include the following:

- The roof sheeting is self-supporting and spans from one side of the dwelling to the other without the benefit of roof beams. This means that the internal ceilings are not fixed but merely glued to the underside of the roof sheeting. The ceilings have since come unstuck in a number of places. Also, there being no insulating layer of air between roof and ceiling, solar heat is transmitted directly into these homes making them uncomfortably warm in the summer.

- The window detailing is such as to fail in the exclusion of either dust or rainwater.

- Doorways are poorly detailed at the threshold and fail to exclude rainwater.

- Waste and water pipe openings in the bathroom/WC wall area have not been sealed properly and leak during rainstorms.

- Walls are beginning to show signs of external cracking owing to poor detailing of butt-jointing.

- The concrete apron surrounding the house is beginning to show signs of drift and large gaps are appearing between it and the wall.

- The external detailing between roof sheeting and wall is such as to allow rainwater penetration.

- In addition to the above, points 4 to 7 agreed to verbally between the two men were not met nor was the roof guttered.

Smith identified these problem areas and presented a list of these grievances to Bricklaaier who took no action in their regard. When Smith presented this same list to the Building Society, Bricklaaier replied in a letter to the Building Society that he had attempted to gain access to the property in order to do the necessary maintenance but alleged that he and workers had been met with aggressive and abusive behaviour on the part of the owner. Smith denied this and finally Bricklaaier was prevailed upon, under pressure from the Employers and the Building Society, to return to the site. There he conducted maintenance of a minor nature to the windows and ceilings which has subsequently proved ineffective and of short duration.

Smith, unhappy with the results, also began to share his experiences with his neighbours, all co-workers at the same firm, who had also entered into similar deals with Bricklaaier. They discovered that not only did they hold common grievances in regard to the technical performance of their homes, but that Bricklaaier had also been inconsistent in his quotations for the exact same structure from one client to the next. Four examples taken at random illustrate this point:

Mr Smith, quoted R16,500, paid R19,500 in August 1986.

Mr Jones, quoted R16,500 in September 1986.

Mr White, quoted R18,500 in October 1986.

Mr Black, quoted R17,500 in October or December 1986.

Subsequent inspection of these dwellings showed them to be identical in all respects barring some minor details such as a different pattern to the front door, the colour of bathroom tiles and the length of towel rack, none of them sufficient to explain such wide fluctuations in Bricklaaier's pricing structure. The pricing pattern was also not consistent with escalations through inflation or rising costs of construction. It becomes clear therefore that Bricklaaier's quotations were not guided so much by a standard costing structure as a knowledge of the maximum housing subsidy his individual clients qualified for from their Employer.

Although the exact legal status of such a practice is not known, Smith felt its morality to be highly questionable and this only served to fuel the dissatisfaction he felt with the quality of his housing. As a result he and his neighbours decided upon joint action and agreed to present these grievances to the Building Society, the Building Society Attorneys, their own Employers and Union shop-stewards. In view of this the Building Society agreed to waive bond repayments until June 1987 to allow for the matter to be resolved.

Smith and his group then continued their negotiations with their Employers but, meeting with little success, turned to a Lawyer in Uitenhage. This too proved fruitless and as a result they then approached the Legal Resources Centre in Port Elizabeth who agreed to represent them in this matter.

On 22 July 1987 my office was approached by Messrs Smith and Jones who, as spokesmen for their group of some fifty families, requested me to investigate the matter and supply them with a report which their lawyers, the Legal Resources Centre, could use as expert evidence in a possible court case against the builder concerned.

Following this initial briefing the following contacts were made:

the Manager of the Building Society in Uitenhage.

the Building Society's Attorney in Uitenhage.

the Employer's Labour Relations Manager in Uitenhage.

the Legal Resources Centre, Port Elizabeth.

At least three attempts were also made to contact Bricklaaier at his home. A woman who would not identify herself answered the telephone and stated that the person in question was not there and that she did not know where he was nor the time of his expected return. To date Bricklaaier has failed to return these telephone calls. It has since been established that this person moved soon afterwards to an address in the Transvaal.

As the result of these conversations it became possible to establish the chain of events outlined above. In respect to the Manager of the Building Society, it was put to him that:

- The clients had all made bond applications at the Uitenhage branch of the Building Society. This was agreed.

- The Building Society had made interim and final payments to the builder without the knowledge or authorisation of the clients. This was not contested but, in this respect, the Manager confided that he did not consider his clients "sophisticated enough" to know when to sign the money over and that the Building Society often made final payments to the builders once their own inspectors were satisfied that the work was completed.

- The Building Society had not ascertained whether a builder. This was not contested.

- The Building Society had not ascertained whether the plans for these houses had, in fact, been approved by the local municipal authority. This was not contested.

- The Building Society, Uitenhage branch, was not certain whether the construction technology used fell within the bounds of approved Agrement or equivalent certification. This was not contested.

- The Building Society had not requested that individual plans be submitted by the client concerned but had allowed the builder to submit a standard plan on the clients' collective behalf. In this regard the Manager claimed during the course of a telephone conversation on 22 July 1987 that he did not recall the exact nature and quality of the drawing submitted. When a drawing in the client's possession (which had reportedly been stolen from Bricklaaier's vehicle!) was described to him, the Manager admitted that this could, in fact, be the same as the one submitted to the Building Society by Bricklaaier.

In a subsequent telephone conversation later that day, the Manager was confronted with the fact that items (b) to (f) above, could be interpreted to be in direct contravention of the bond application procedures of the Building Society. It was also pointed out to him that the apparently cavalier approach employed by his branch in regards to the Bricklaaier houses at KwaNobuhle was hardly in keeping with that firm's long-standing reputation as a conservative and careful guardian of both its own long-term financial investments and the interests of its bond holders. The Manager replied that black housing was a new field of investment activity and that the urgency of the matter warranted unorthodox methods in order to expedite matters. Finally reference was made to the quality of the drawings submitted by Bricklaaier and that their status as legal documents was highly dubious. The Manager agreed that this appeared to be the case but could offer no reason as to why his branch had accepted them. He offered to investigate this matter further from the Building Society's position.

Sadly it must be reported that the Manager took his own life within 24 hours of this conversation taking place. In respect to Smith's employers, it was established that :

- the Employers had on their payroll a Housing Officer whose duty it was to advise and assist workers in their housing efforts.

- the Employers were seriously concerned with the fact that their workers had ceased bond repayments on the Bricklaaier homes and had encouraged them to resume these in order to maintain their bona fides with the Building Society.

- the Employers had already attempted to assist their workers by requesting Bricklaaier to return to the site in order to carry out maintenance work but that problems had been encountered by the builder in gaining access.

It was then put to the Employers that the major part of the problem lay in the fact that Bricklaaier was bound by the flimsiest of contractual links to their workers, my clients. The Employers agreed that this appeared to be the case and stated that they also had requested copies of these documents from Bricklaaier in order to establish exactly what their workers' legal rights in this matter were. However Bricklaaier had consistently denied either the Employers, the Building Society or the clients concerned, access to these documents. He stated that the employers were now preparing to take a Supreme Court order against Bricklaaier in order to force him to hand over these documents to the clients concerned.

It should be noted that throughout these discussions with the parties concerned - the Building Society, the Employers and the client body - the term "contract" had been used in the loosest of architectural senses. To an architect a contract to build between client and contractor may comprise of a set of working drawings, a schedule of specifications or a contract document or, in some instances, a combination of any of the three. This is significant for it would appear that all three parties concerned had interpreted the term in its narrowest of senses and that, in their subsequent dealings with Bricklaaier, they focused upon the production of a written "contract document". Judging from Bricklaaier's previous behaviour, it was doubtful that any such document existed and, in fact, that the builder's contracts' file contained little more than a flimsy sketch.

However, following the Employer's entry into the fray, the builder was able, after some delay, to produce a number of documents. These were handed over to the Employers some time in September, but are not believed to cover more than about half of the fifty contracts involved.

Some of these have since been inspected by the clients concerned who have repudiated them, their contents and their signatures. The documents do not appear to have been properly witnessed and are poor photostat copies of poor photostat copies. One client in question, Mr Jones, has denied that the document carries his signature, claiming it to be a forgery, and has pointed out that its dating predates his first approach to Bricklaaier by some three months.

The allegation that Bricklaaier may have forged a set of documents in order to meet external pressures from the Building Society and the Employers is therefore inescapable.

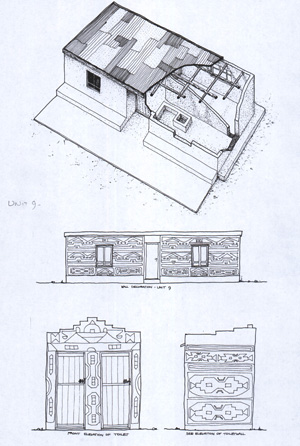

CONSTRUCTION TECHNOLOGY

The average "Bricklaaier" structure is 5.260m wide by 12.700m long and stands on a concrete raft of unknown thickness. The walls are timber frames, constructed in 114 x 38 SA Pine clad externally and internally with 12mm gypsum board. The external board appears to be of a type of gypsum and resin compound called "Rhynoshield" which is claimed by its manufacturers to be water resistant, although, strictly speaking, the board lamination itself is not. However, at least one instance is known where the outside wall cladding was done in 12mm chip board. All internal wall cladding was done in standard gypsum board (called "Rhynoboard") which is not water resistant. All wall panels are secured to the concrete floor raft by means of hoop iron ties nailed to the timber framework. No sign of DPC at floor level was observed on any of the sites visited. The external wall finish has been rendered in Marley Acrylcote which has reportedly been given a 10 year guarantee by its manufacturers. It is not known whether its application in this particular instance meets with the manufacturers' specification. The whole structure is butt-jointed, but in many cases no cover strips have been applied to external panel joints and hairline cracks have already appeared. No plastering of internal wall panels has taken place and none of the timbers have been treated with preservatives.

The roof sheeting, a single-span asbestos cement Canalith profile, has been fixed directly to the timber framework below. The ceiling, probably a gypsum board, has been glued directly to the roof sheeting itself by means of a rubberized contact adhesive.

External doors vary in their make-up. The single leaf solid pine panel door has mostly been used for the front while a double leaf pine stable door, framed, ledged, braced and battened, serves at the kitchen entrance. Internal doors are all of the hollow core variety.

Windows are top-hung butt-jointed pine frames with no reveals, weather bars or drip-moulds. Window furniture is partial and rudimentary and the windows do not open fully owing to their detailing at the lintel which impedes their full outward swing.

All floors are carpeted and have no underfelt, save the kitchen, bathroom and WC areas which are lino-tiled.

A concrete apron approximately 600mm wide has been cast in situ about the outside perimeter of the dwelling.

TECHNOLOGICAL PERFORMANCE

Client dissatisfaction with the technological performance of the above structure may be summarised as follows :

- Widespread water and dust penetration at window and door openings.

- In some instances, water penetration at eaves' height.

- In some instances, water penetration at plumbing points.

- In some instances, water penetration at DPC height.

- Widespread hairline cracking at the butt-jointing of external wall cladding. In at least one case where chipboard was used, swelling and breakup of the material was already taking place, barely nine months after the building was handed over for occupation.

- Widespread failure of ceilings.

During the course of various site inspections, all of the above complaints were shown to be valid. A subsequent accident at the dwelling of Mr Smith in November 1988 has also shown them to be highly imflammable. Fortunately, on this occasion, the inhabitants escaped without injury. However it is my contention that the real problems inherent in this technology have barely begun to manifest themselves. For the purposes of the discussion which follows, it is proposed to deal with these problems under three headings :

- Short term problems: an inherent part of any building project which should be corrected within six months of the building being handed over for occupation. In cases where financing is in the hands of money-lending institutions, the scope of such a process is somewhat limited, as there is no financial incentive for the builder to return to the site and make good. The client is forced to rely upon the builder's goodwill and continued institutional promises of builder patronage. Items (2), (3) and (4) mentioned above appear to fall into this category and may be handled by any competent builder cheaply and easily.

- Medium term problems are those which may manifest themselves immediately or with time but which are inherent in the system concerned. Items (1), (5) and (6) above are such problems which are not rectifiable either cheaply, easily or immediately and may require the services of a specialist. All are patently flawed and will require upgrading of the wall, window and roof technologies concerned. These may be neither cheap nor easy to implement.

- Long term problems: as in the medium term, these are also inherent in the system concerned but have to do with the overall performance of the structure involved. Although short and medium term problems may be resolved by technological means, there is no guarantee that physical or psychological elements of dissatisfaction may not reappear in the long term. Two areas of potential long term technological dissatisfaction suggest themselves:

- Where, in the not-too distant future, a family may decide to extend their present abode, using a different technology.

- Where a material has been used in a context inappropriate to the long term realities of habitat performance. Although I do not necessarily question the environmental properties of a material such as "Rhynoshield", it is difficult to predict its performance under certain conditions, such as, for example, the continued battering it might suffer, over the years, from a child's football.

Thus, although it is possible to arrive at a number of short and medium term solutions to the problems presented above, these must, of necessity, be weighed up against the long term performance, human expectation and financial investment potential of the structures concerned.

FINANCIAL CONSIDERATIONS

The estimated cost of the average dwelling erected by Bricklaaier for the clients was R13,000. This was based upon prices of materials and labour current between July and September 1986 and includes a 10-15% profit margin for the builder concerned. This compares favourably with a similar costing exercise done in 1986 by the Urban Foundation which costed a similar structure at R12,500.

This means that, assuming an average selling price of R18,000 per unit, each house realised a return of 42% on its production cost. Considering the nature of the labour used and the duration of construction time, it is probable that this profit margin was even higher.

The Quantity Surveyor's report showed quite clearly that the cost of providing the facilities claimed by the client as having been promised by the builder as part of their verbal agreement is, in fact, realistic. Considering the technology concerned, the client had every right to expect a dwelling with electricity and geyser, standard windows, guttering and functional ceilings as part of his contract price. He also had the right to expect a house which could perform effectively for the duration of its bond life, if not longer.

However in the light of this technology's current state, serious doubt must be cast upon its continued performance, either in its current or upgraded form.

This pricing has subsequently been borne out by an insurance company who, working independently, estimated the replacement cost of one of these structures to be R11 088,59, this being the sums paid out to Mr Smith, the owner of the unit which burnt down in 1988. Smith's bond was R19 000and although he wanted to use the insurance money to repair the burnt out shell of his home, the Building Society has not permitted him to do so and has insisted upon its demolition instead. Thus at this point in time Smith is paying off a bond of R9000 for a house which is no longer existent and which he has no hope of replacing.

CONCLUSIONS

From the outset this investigation has been faced by a tangled web of facts and events which have prevented a quick and easy conclusion being arrived at.

Firstly we are faced by the inexperience of a body of clients who, in their need to achieve a quality of life for themselves and their families, naively entrusted their savings to the efforts of one man without the security of a firm contractual undertaking.

Secondly we have a Building Society who, faced with a number of hard realities, decided to live up to its widely advertised social responsibilities and extend its services to areas where it has never operated before. In the process it found itself in situations beyond its previous experience and, of necessity, was forced to invent new means and procedures of operation.

Thirdly we have a businessman operating in grey areas where the rules are being changed almost daily and many of the conventional business constraints are being bypassed on the basis of trust between parties in an effort to meet certain social emergencies.

During the course of this investigation, numerous abuses, errors and flaws have been uncovered. Fortunately it is not for this report to apportion blame or find faults. That is the work of a court of law. However, in the process, a number of ideas for guidelines have emerged and, in this context, warrant expression.

- Although the eagerness shown by the Employers to be involved in the housing affairs of their staff is commendable, the course of events in this affair has shown their management to be lamentably unaware of the issues and problems involved. At the very least the ramifications of an experimental building technology should have been examined by their Housing Officer and consultant technical staff (such as an architect, engineer or quantity surveyor), in conjunction with the probable recipients of this housing.

- A similar comment may also be made of the Building Society whose pioneer work in black housing in this country has not gone unnoticed in many professional circles. In their case a return to certain procedures tried and tested in the context of standard (white) housing may not be inappropriate.

- The Trade Union concerned could have and may still play an important role in representing the interests of their members.

- In the case of all three above, a comprehensive programme of education in issues of housing must still be initiated in this country. To date all such have been passive but a more active and even aggressive approach is clearly indicated.

This case study also brings into question the role currently being played by both the private sector and the building societies in the housing process. The shortage of certain types of housing in our urban areas since the 1950's has always ensured that the awarding of building contracts and the allocation of dwellings has invariably been tainted with a degree of corruption. However, since the government has opened up the field to the private sector, the opportunities for such "enterprise" has multiplied ten-fold. A number of senior personnel and officials associated with the provision of housing in this country recently expressed private concerns that this area is rapidly becoming the happy hunting ground of unscrupulous entrepreneurs with a carpet-bagging philosophy. This has been most particularly true in regions where controls are most relaxed, such as the newly-emergent black municipalities and South Africa's so-called homeland states. Another curious and disturbing aspect of big business involvement in black housing is the fact that many large building concerns operate in black areas under the guise of subsidiary companies with different names. The reasons for this can only be the subject of speculation.

In this respect a critical look should then be taken at the workings of financial institutions such as building societies and banks. While it is true that their role is to lend money for the purpose of housing, their reluctance to enforce realistic retention figures fails to safeguard their clients' - and hence their own - interests. There have also been documented cases where this attitude has interfered with the work of the architect as project leader. While it is true that housing has now become one of this country's major social issues, the eagerness of building societies to adopt a mantle of "social responsibility" should be tempered by the realities and problems of the building industries: poor craftsmanship, rogue builders, insolvencies and unenforceable product warranties. It is true that housing newly urbanized communities requires the creation of new methods of funding and administration. However, it is equally true that financial institutions are confronted with a critical and demanding clientele whose aspirations are as bourgeois and as middle class as any they have encountered in previous eras. Their contribution to housing, therefore, must be guided by the consideration that they have an additional responsibility to protect the rights of their client body.

POSTSCRIPT

This report was originally submitted, in a much abridged form, to Architecture SA, as part of a larger critique on housing entitled "Architects, Sociologists and Carpet-Baggers". This was the carpet-bagging part of it. Unfortunately the owners of the journal demurred on its publication because it reported on the suicide of a building society manager and involved a large motor company, neither of them named in or identifiable from the text. Ultimately this article was printed with this section censored out, thus making nonsense of its title and its conclusions. Literary merit aside, there was no legal reason for this action. It is, however, symptomatic of what many people consider to be a wider and more deep-rooted problem: the inability of the architectural profession to metaphorically roll up its Dior shirt sleeves and get their Gucci shoes scuffed in the real business of resolving one of this country's most pressing social problems. The Editor of Juta’s South African Journal of Property had no qualms in reproducing a more comprehensive article on this case study, with no moral, financial or legal repercussions. (FRESCURA, Franco. 1990. KwaNobuhle Timber Housing: A Case Study. Juta’s South African Journal of Property, Vol 6, No 3, 1990. 47-55.)