Housing issues

Much of the discussion which has surrounded the field of housing in this country since 1976 has focused upon the failure of the architectural profession as a whole to invest its not inconsiderable design talents in the resolution of this problem. Although some of the blame may be laid at the door of central government and local authorities who, up to recent times consistently refused to commission architects in this work (Lazenby, 1977), the profession also stands indicted in that it has failed to develop the necessary grass-root and community-orientated skills necessary to large-scale housing work. Thus, in spite of the efforts of such individuals as Noero in the Transvaal and Haarhoff and Harber in Natal, much of the architectural research being conducted in low-cost habitat has remained almost exclusively the province of the NBRI and a small band of concerned academics within the universities.

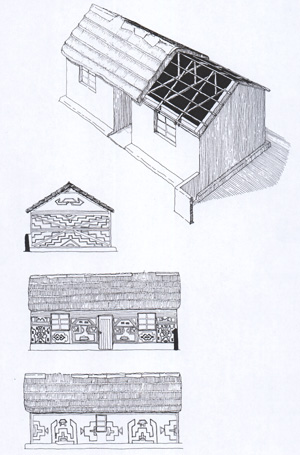

Part of the problem has undoubtedly lain in the economic realities of housing and many an architectural practice, in the past, has found its ardour for social reform cooled by the meagre returns available for its efforts. However, some housing projects conducted by architects in more recent times have shown even greater failings than was previously anticipated. One need look no further than the post-modernist confections served up by designers in the Ciskei (Frescura and Volpe, 1988) and Bophuthatswana (Gallagher Arup Samson Inc, 1987) to realise their authors' eurocentric values and ignorance of things African.

The failure of these projects lies not so much in the fact that the architects concerned have tended to use local decoration as a pastiche layering to hide their simplistic efforts as in their inability to grasp the essential nature of such aesthetics. Indeed the simple activity of wall painting is associated in rural life with the fertility, group identity and political rights of women (Frescura, 1985). The absurdity of translating such symbolism to an urban habitat is therefore self-evident. It is not for nothing that, during the social unrest of 1976, the students of Ngoya, Zululand, and Turfloop, Pietersburg, targeted for arson those buildings which the architects, in their wisdom, had endowed with rural decorative motifs, the library, the student's union and the administration block, which were seen as symbols of white domination and ideological repression. Such rejection of rural aesthetics by an urban black clientele should not be seen as a breaking of historical links between the two communities so much as a forceful denial of the cultural and political stereotypes created by whites as a tool of their political expediency. Therefore architectural efforts to achieve some kind of post-modernist regional aesthetic based upon rural motifs must also be seen to promulgate visually the same racial bigotry which has blighted South African society since 1948.