DESIGNING FOR A DEVELOPING ECONOMY

Franco Frescura

PREAMBLE

Some weeks ago the Editor of this journal requested me to examine, in an essay, some of the problems and pitfalls facing the work of designers in rural areas. I have found this difficult to do for a number of reasons. Most of these center about a perception, which appears to have been gaining currency in recent times, to the effect that urban blacks somehow comprise a separate "cultural" group from their rural counterparts and should therefore be given different treatment. Not only is this false, for it ignores the social, cultural and economic links existing between the two communities, but it should also be seen as part of the same governmental obsession which has already divided South Africa's black population into ten "ethnic" blocks. These divisions have largely been rejected by the people concerned, as have been attempts to create an eleventh constituency out of a group whose urban background has now placed them beyond "ethnic" classification. Thus the problems being faced are not based upon a "cultural" differentiation which some people perceive to exist between one black group and another, or between urban and rural man, but between a European-based socio-economic structure and that indigenous to southern Africa. This means that although physical or social contexts may appear to place a building in either an urban or a rural setting, the problems and value systems involved should be seen to be common to both. For the purpose of this paper therefore I propose to concentrate upon those problems I perceive to be facing designers operating within the broad definition of a developing economy.

SOME PROBLEM AREAS

Most of the problems encountered by designers working in the context of a developing economy may be traced back to three primary areas of concern:

A. PROBLEMS OF PERCEPTION

These relate to the difficulties experienced by professional designers in formulating their briefs and in understanding the nature of their clients needs and realities. This is a failure liable to occur at any stage of the design process and is probably the most common problem experienced by architects in developing areas. It may be attributed to the fact that, when faced with a design problem, many professionals tend to interpret the social, technological, economic and cultural factors placed before them in terms of their own experience and value structures and not those of their clients. Although more often than not this may be attributable to the insensitivity, or the ignorance, of the designer concerned, some have gone so far as to claim that to do otherwise is tantamount to a form of racism and thus deliberately set out to ignore such evidence.

Examples of this abound throughout the developing world. One need only look at the new town of Chandigarh in India where, given an architectural tradition reaching back two thousand years, the Swiss le Corbusier imposed a rigid grid-iron plan upon the landscape and populated it with uncompromising concrete structures built in a brutalist International style. Not only that but he also serviced the town with six lane highways - this is a community which relies on oxcarts and bicycles as its predominant forms of transport.

Another piece of architectural foolishness may be found at Brasilia, where Niemeyer's designs for Brasil's new administrative capital effectively bankrupted that nation and forced it to make foreign loans which are still being repaid forty years later. A similar gaffe was perpetuated by the military rulers of Nigeria who, during the early 1970's, found themselves endowed with a cornucopia of new-found wealth from their oil resources and thus decided to embark on an ambitious programme of public works. As a result they ordered the import of some 90 million tons of cement. It was only when foreign cargo ships laden with cement began queuing up off Lagos harbour that it was discovered that the country had off-loading facilities to handle only 7 million tons per annum.

B. PROBLEMS OF IMPLEMENTATION

These relate largely to areas of technology where a design is based upon preconceived assumptions unsupported by empirical on-site observations, or the implementation of design solutions which fail when local conditions and technology prove unequal to the demands placed upon them. In this respect South Africa can boast of a few home-grown blunders of its own: like the time when the people of Johannesburg looked on with understandable anxiety as one of the new Standard Bank's massive prefabricated beams hung suspended precariously twenty storeys from the ground because of an engineering miscalculation about the differential movement of concrete structures; or, more recently, the overloading of the new Stock Exchange's air-conditioning system after one of the mining companies had erected its prestige reflective glass-plated headquarters on the southern side of their building.

C. PROBLEMS OF EXPECTATION

These relate not so much to the technical performance of a structure as to the expectations which the client will have of his building once it is erected. The most common failure in this regard may be found in the field of domestic architecture where a designer's unexplained drawings can arouse expectations of scale, form and finishes which the final product does not meet. Monty Python's satirical sketch of an architect providing his client with a well-appointed abattoir when the brief required a block of flats is not as surrealistic as it sounds, especially when the architect excuses himself by stating that he had "not divined the client's attitude" towards his tenants!

It will be evident that design failures are not necessarily the result of any one of these factors acting individually but, rather, are often the outcome of any number of them acting in combination with each other. Perhaps these points are best illustrated through a number of case studies.

BISHO, THE WORLD'S FIRST (AND ONLY) POST MODERNIST CITY

The boundaries of what was to become known as the "Ciskei" were established as early as 1913 when parts of this region were set aside by the Union Government for exclusive black settlement. During the 1960s and 1970s the area was used by South Africa as a dumping ground for the forcible resettlement of many black residents of the Cape. As a result some villages became little better than rural slums where unemployment and starvation were endemic. The Visagie survey of 1978 found that kwashiokor affected 27% of all infants in the 6 to 23 month age group. As late as 1985 the Herman/Windham study established that between 1970 and 1983 approximately one infant in every five born in the region died before it reached the age of five. In 1980 the Quail Commission stated that 95% of Ciskeian workers in employment held jobs in white South Africa.

When the Ciskei opted for independence in 1981 under the South African Government's Bantustan policy, it did so with the consent of only a small minority of its population and against the specific recommendations of its appointed consultants. In the process it inherited a legacy of poverty unequalled in modern-day southern Africa.

The development of Bisho, the Ciskei's new capital, must then be viewed in the context of these factors. The town lies some six kilometers north of King William's Town on the main road linking the Cape to the Transkei and Natal. Its location was dictated by a wish on the part of the Ciskei to place an economic stranglehold upon the white community of King William's Town who, Prog, Nat and HNP, stand united against incorporation into the homeland. When questioned on the subject residents point, with some reason, to the Ciskei's long history of political and economic mismanagement: the location of a new hospital below the flood plain of the Keiskamma River by Israeli "experts"; the building of a multi-million Rand "international" airport (soon to be followed by an equally expensive "international" hotel) outside Bisho; the purchase of a R36 million jet aircraft which cannot obtain a permit to fly; and a string of internecine rifts, vigilante violence, attempted coups d'etat and military invasions which have typified the government of President Sebe.

The visitor approaching Bisho is immediately struck by the surrealistic image of a town rising abruptly out of the landscape. The odd juxtaposition of a stranded CBD, ready-made and unsupported by a residential component, against a backdrop of wide-open veld, is bizarre to say the least. As evening approaches, day-trippers disappear into the veld leaving the streets empty for the goats that amble along, "wending their weary way" from nowhere to nowhere.

The Master Plan for the town has clearly been disregarded by the architects, as buildings jostle with each other, each clamouring for attention. Neighbours are rudely ignored and spaces between buildings carelessly abandoned to dust and litter.

Most of the buildings are treated in the Post-Modern idiom, a style of architecture intended to facilitate meaningful communication. Ironically, virtually no references are drawn from the region or the culture of the Ciskeian people. Unimpeded by the constraints of an established urban setting and a sophisticated and critical audience, the architects are having a field day. Bisho is a town that is as unlovely as it is apparently unloved. Perhaps Italo Calvino was right when he said that "a town without old buildings is like a man without a memory"; but the problem with Bisho lies not only in its lack of old buildings but in the quality of the new.

The designers of Bisho will have much to answer to in future times. Why, for example, did they lend their skills to build what is so obviously a fantasy town relevant only to the dreams and aspirations of a small minority of Ciskeians? Why was it permitted to develop on its present site when neighbouring King William's Town remains so obviously the region's major economic centre? Why does its architecture mirror the effete fashion of an American culture half a world away and ignore so obviously local forms and traditions? Why, above all, will designers not learn to say "No" to a brief which is so obviously flawed?

THE SOWETO OLD AGE HOME

This project was initiated in about 1982 by a group of South African Rotarians who, for reasons of their own, wished to build what would have been Soweto's (and possibly this country's) first old age home for blacks. Although the design was handled by a firm of prominent Johannesburg architects, I was asked by the community concerned to join the committee in an advisory capacity. This was owed more to the fact that the community was having difficulty in communicating with the architects than with the latter's design abilities, which were never brought into doubt.

It soon became apparent that a number of important questions were being asked which neither the architects not the clients were able to answer comprehensively. These hinged about the concept of an "old age home" which, the community felt, originated in white society and had no place amongst blacks, who pride themselves on the fact that they include the elderly into their extended family structures. Whites, on the other hand, were perceived by them, rightly or wrongly, to have a throw-away attitude towards their parents, their spouses and their children whilst bestowing undue care and attention to old buildings, books and artifacts. Other considerations also arose, such as the height of beds, attitudes to death, religious functions, connections with the community and the ability of the buildings to convert to other functions should the project not succeed.

Ultimately, however, the project was torpedoed by simple financial considerations: the clients were prepared to spend R1.5 million upon the buildings but had not taken into account the fact that such an institution would require an approximate R20,000 per week to keep it operational. The community certainly had no such means at hand and when the Government indicated that it would not be subsidising this venture, the project was abandoned.

INKONZO YOVUKO, CHURCH OF THE RESURRECTION, PORT ELIZABETH

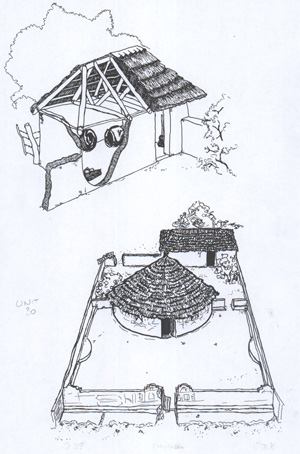

This project was initiated recently by the (black) Anglican community of Walmer Township, Port Elizabeth in conjunction with the Department of Architecture at UPE. It illustrates an attempt to bring together the cultural traditions of Xhosa architecture with the liturgical needs of a Christian community to produce a building which is both unique to this region and conforms to the limited financial resources of the clients.

The building itself has an ufokona or square plan but a series of four apses gives it an overall cruciform shape. This is important for the site lies near the airport and will be seen from the air by passengers arriving into or departing from Port Elizabeth. The symmetrical plan focuses upon a central altar, placed upon the site of the traditional iziko or hearth, the source of light, warmth and nourishment in a traditional dwelling. This generates a circular seating plan, a pre-requisite of the client's brief, which harkens back to customary Xhosa gathering forms. A second altar, the entla, has been placed in a chapel apse to the rear of the church. This is a location associated in Black tradition with the ancestors and is therefore of great spiritual significance. It also allows for the performance of the Mass along more conventional lines thereby fulfilling the architectural brief of the more conservative section of the congregation.

Entry to the building is gained via a traditional isitupu or entrance step which leads into an entrance lobby opposite the entla altar. This creates a central axis within the church dividing its interior into the traditional icala Lamadoda, the side of the men where the vestries are located, and the icala Labufazi, the side of the women where the kitchen is also found. This division is, of course, only metaphorical, but it does give rise to a further reference to traditional Xhosa life. The side of the men is also known as the "side of life" and hence was considered to be the natural site for the baptismal font.

The roof structure is further reminiscent of traditional Xhosa building methods. The structure over the main body of the church is supported by four main trusses called the isibonda held together at the apex by cross-members called the indibano. This is further reinforced by an umqolo or ring beam whilst the intsika or centre post, used as an additional support to the roof during thatching and then cut off below the cross-piece, is allowed to emerge through the isiciko or apex capping piece to become a four directional cross. A further cross, made from timber extracted from demolished squatter shacks in Walmer, hangs below the cut-off intsika. The lower two thirds of the roof are sheathed in corrugated iron whilst the top third is covered with translucent sheeting. This not only sets out to evoke the imagery and soft lighting of a partly thatched roof but it also makes symbolic reference to the abakwetha hut, a building of religious and spiritual significance which the Xhosa traditionally leave partly unfinished.

The brief was formulated and the design was executed following extensive consultations with the community concerned. This involved not only prolonged meetings with the larger congregation but their representatives also took extensive part in the design process, often sketching their ideas out themselves or manipulating the basic elements of a 1:50 scale model. As a result it was found that the general community was highly literate in both the reading of two-dimensional plans and the use of symbolic space and architectural metaphors. The role of the designer in such a process was in no way limited. Indeed their participation enriched both the design and his experience and his work was given added meaning and dimension by being brought into the ambit of the larger community. Similar personal experiences have also been shared in the conversion of a Johannesburg warehouse into Open School premises, the provision of housing for some 230 families in Soweto and, more recently, the design of a self-help project aimed at providing a community of some 400 Ndebele with reticulated water and sewage services in Bophuthatswana.

SOME CONCLUSIONS

When, in 1923, Corbusier wrote words to the effect that society had a choice between revolution and architecture, his cry became the rallying call of a whole generation of Modern Movement architects. They acted in the belief the nature of the built environment had the power, good or bad, of bringing about radical changes in the society it housed. Despite the fact that this hypothesis has since been shown by sociologists, psychologists and planners to have been based upon a number of false premises, architects of today persist in the fond belief that their sole responsibility to the betterment of society is to provide it with beautiful buildings.

The relevance of such an attitude in the context of a developing or under-developed economy such as ours must be severely questioned. For one thing local architects are traditionally perceived, by white and black alike, to be closely allied to political systems which favour the powerful and the rich. For another architects tend to service the needs of those best able to afford the luxury of a specialised designer. Black society has neither a tradition of specialised builders nor does it have a name for them. The work of the architect therefore is seen as being largely irrelevant to the needs of a future South African society.

This means that a progressive-thinking architect, seeking to make a socially valid contribution under the present political system will find his role and the scope of his operation seriously curtailed by a variety of factors. Many an architectural firm's ardour for social reform has been cooled by the meagre returns made by such a market or by the bureaucracy and corruption involved. Ultimately he will be forced into a position of having to make what some observers in other fields have described as the "liberal compromise". In architecture this means that he will have to define for himself a role that neither links him to government nor big business but still allows him to earn a living for himself and his dependants. This means that in such fields as black housing, where his work can at best be described as the sugar coating upon an extremely bitter pill, the architect will be able to derive a measure of social credibility and approval from the community concerned whilst knowing perfectly well that his work does not begin to address the problem of housing at its root causes. This calls for a dedicated missionary attitude towards architecture or, at the very least, a degree of ideological motivation which, I fear, few architects have displayed publicly to date.

The case studies discussed above provide a number of important lessons. Through them it becomes possible to formulate guidelines which, I believe, should characterize the work of a progressively minded architectural practice of the future. These include the following important features:

- An orientation towards developmental, labour-intensive work as against commercial, capital intensive and largely urban projects.

- Clients will be included as active participants in the design process, and not as the mere consumers of an end product.

- Clients will tend to be whole communities or their representative bodies rather than individuals. The work will therefore entail a high degree of consultation with the client body as a whole.

- Projects will be aimed at local job creation and economic development within the communities concerned rather than at the generation of wealth for large scale capitalist enterprise.

- In some instances the architect may be part of and not necessarily the leader of a multi-disciplinary team of experts.

- The design should be part of a larger planning process which questions the basic premises of the brief. If the brief fails to meet some of the criteria outlined above, then the commission may be turned down or the brief amended.

- The practice would be involved in the educational process of young architects-to-be either through direct participation in formal university teaching or through an informal in-house training programme aimed at developing the architectural skills of young draftsmen prior to their entrance into university.

- The practice would incorporate in its project development an active programme of research and data publication. It is probable that architects belonging to such a practice would also be actively encouraged to pursue post-graduate studies.

To summarise, it is probable that progressively minded designers, conscious of their social responsibilities, will opt to exercise their skills in projects whose scope and size will allow them to remain in full control of the production process and in close contact with their client rather than ventilate their collective ego through the kind of antisocial megalomania which punctuates our urban skylines. It goes almost without saying that police stations, sectarian monuments, corporate headquarters, Bantustan Legislative Assembly halls and District Six condominium developments will not feature in their curriculum vitae.

POSTSCRIPT

This paper was originally presented at the African Studies 33rd Annual Meeting on Africa: Development and Ethics, Baltimore, 1-4 November 1990. It was subsequently published under the title of Designing for a Developing Economy, in Building, 19 April 1989: 11-15.