ARCHITECTS, SOCIOLOGISTS AND CARPET-BAGGERS -

A Review of Some Housing in the Eastern Cape

Franco Frescura

Much of the discussion which has surrounded the field of housing in this country since 1976 has focused upon the failure of the architectural profession as a whole to invest its not inconsiderable design talents in the resolution of this problem. Although some of the blame may be laid at the door of central government and local authorities who, up to recent times consistently refused to commission architects in this work (Lazenby, 1977), the profession also stands indicted in that it has failed to develop the necessary grass-root and community-orientated skills necessary to large-scale housing work. Thus, in spite of the efforts of such individuals as Noero in the Transvaal and Haarhoff and Harber in Natal, much of the architectural research being conducted in low-cost habitat has remained almost exclusively the province of the NBRI and a small band of concerned academics within the universities.

Part of the problem has undoubtedly lain in the economic realities of housing and many an architectural practice, in the past, has found its ardour for social reform cooled by the meagre returns available for its efforts. However, some housing projects conducted by architects in more recent times have shown even greater failings than was previously anticipated. One need look no further than the post-modernist confections served up by designers in the Ciskei (Frescura and Volpe, 1988) and Bophuthatswana (Gallagher Arup Samson Inc, 1987) to realise their authors' eurocentric values and ignorance of things African.

The failure of these projects lies not so much in the fact that the architects concerned have tended to use local decoration as a pastiche layering to hide their simplistic efforts as in their inability to grasp the essential nature of such aesthetics. Indeed the simple activity of wall painting is associated in rural life with the fertility, group identity and political rights of women (Frescura, 1985). The absurdity of translating such symbolism to an urban habitat is therefore self-evident. It is not for nothing that, during the social unrest of 1976, the students of Ngoya, Zululand, and Turfloop, Pietersburg, targeted for arson those buildings which the architects, in their wisdom, had endowed with rural decorative motifs, the library, the student's union and the administration block, which were seen as symbols of white domination and ideological repression. Such rejection of rural aesthetics by an urban black clientele should not be seen as a breaking of historical links between the two communities so much as a forceful denial of the cultural and political stereotypes created by whites as a tool of their political expediency. Therefore architectural efforts to achieve some kind of post-modernist regional aesthetic based upon rural motifs must also be seen to promulgate visually the same racial bigotry which has blighted South African society since 1948.

As is often the case in such matters, it was not an architect but a sociologist, Lawrence Schlemmer, who was left to demonstrate the manner in which designers could research their briefs and test out data at a community level (Schlemmer and Moller, 1982). His survey of housing preferences among a number of Natal communities in about 1982 exploded a number of white myths and preconceptions and showed that the provision of human habitat was subject to a variety of cultural, economic and environmental perceptions which had a direct effect upon housing aesthetics. Although some of Schlemmer's premises were undoubtedly un-architectural, he nonetheless tackled the subject from a consumer point of view and showed that many architectural preconceptions of aesthetics were eurocentric and often based on Victorian and colonial stereotypes.

Such a pragmatic if different approach to housing was also investigated by Hardie (1980), Frescura (1985) and, more recently, Mills (1985), whose work has shown the role of expressive space and traditional hierarchies in the conceptual creation of home. Although much of this research has since been published, housing designers have shown a marked reluctance to give these findings practical implementation. For this reason then, three surveys recently commissioned by clients active in the field of housing in the eastern Cape appear to be more important than either their size or scope would initially suggest.

THE MOTHERWELL CASE STUDY

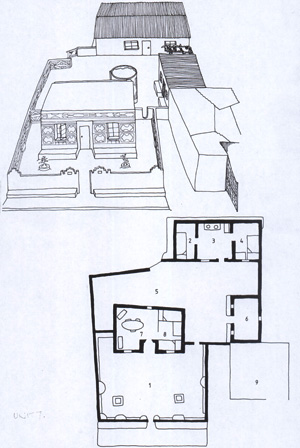

The Motherwell Neighbourhood Unit No 2 is a predominantly region situated some 19km from its central business district. It was established in or about 1984 by the Eastern Cape Development Board (ECDB) and houses some 10000 persons living in 2147 units. These follow the basic NE51/9 plan developed by Calderwood in 1951, consisting of four rooms and an internal bathroom. The dwellings however were not built as a whole but rather formed part of an experiment whereby the ECDB constructed the basic shell and sold these to prospective clients for R4500. The residents were then expected to subdivide the internal space according to their individual needs and budgets. Plans for the standard NE51/9 were made available to purchasers and for an additional R1200 the Board also provided them with the materials necessary to make this conversion. (Frescura and Riordan, 1986)

This survey, sponsored by the Builders Warehouse of Port Elizabeth, was motivated through a general concern for the quality of life in urban areas such as Motherwell. It therefore sought to establish a data base in four major areas of concern:

- The average Motherwell resident's response to the shell-housing experiment.

- The functional usage of space in the average Motherwell residential unit.

- The average resident's response to the use of certain materials and finishes.

- The average resident's response to certain basic house forms and aesthetics.

The collated findings made for interesting reading. For one thing the majority of respondents expressed predominantly negative feelings in regard to their dwellings. During the course of three separate sets of questions, residents were almost unanimous in their condemnation of the quality of their housing. Most complaints could be traced back to the shell-house nature of their homes and only a small minority focused upon other environmental factors such as dust. Generally speaking residents perceived their dwellings as offering little security to either themselves or their property, being poorly built, poorly finished, too small in size, poorly insulated against the dust and elements and, considering their nature, relatively expensive. The only positive feature, which met with unanimous acceptance, was that of home ownership. The idea of owner participation in the building process was almost totally rejected, many people perceiving it to be more expensive, in the long run, than if the total house package had been provided for by a skilled builder.

The questions relating to space usage provided some important insights. Predictably the kitchen emerged as a primary social focus which often doubled as both an entertainment, catering and cooking area. It was significant to note that just over half the respondents interviewed applied the western concept of a lounge to an area which also included cooking facilities. Understandably three-quarters of all respondents wanted the kitchen to be the largest room in the house. The various bedrooms were perceived primarily as areas of individual privacy where entertainment and socialising took place.

A number of space-saving features proved acceptable to the majority of respondents. These included the use of a kitchen work-top to separate entertainment and cooking areas, internal sliding doors, built-in cupboards and bunk beds for children. Brick and concrete block construction were equally acceptable but timber, asbestos sheeting, galvanised iron and mud-and-plaster walls were all rejected almost unanimously.

In their choice of dwelling forms, Motherwell residents showed a marked preference for a western and suburban housing aesthetic. The lean-to forms reminiscent of farm and squatter architecture were rejected outright for the reason they had flat roofs, the standard NE51/9 being preferred as an alternative almost unanimously. On the other hand a significant number of people, nearly 30% of the survey, did not automatically reject the same NE51/9 in favour of a more suburban aesthetic, indicating that perhaps the scale of such housing might provide a valuable lesson for future designs. However over 95% of respondents did not think of their homes as being beautiful. Improvements which met with overwhelming approval were bigger windows (98%) and the addition of a verandah to the house (99%).

It was interesting to note the degree to which residents expressed total rejection of the principles of row or semi-detached housing, stating that these residential forms did not allow for extensions and improvements to the dwelling and that shared house boundaries led to quarrels with neighbours. Housing higher than two storeys was similarly dismissed.

THE KWANOBUHLE CASE STUDY

KwaNobuhle, whose name in Xhosa literally means "a place of beauty", is a dormitory town situated some four kilometers south of Uitenhage, near Port Elizabeth, in the Eastern Cape region. Its origins date back to 1967, when it was established in order to house those residents of the old Uitenhage suburbs of Langa, Xaba and New Gubbs who, at that time, were being displaced from their homes by the Local authorities under provisions of the Group Areas Act. KwaNobuhle's reputation as a dumping ground has been maintained right up to present times when, in a brief seven months, between May and November 1986, 42% of the town's current population was forcibly removed there from Uitenhage. Although the victims of this latest piece of Governmental social engineering were allocated permanent stands and given the temporary loan of army tents, they were provided with no form of housing and were expected to erect their own shelters. Although some of the new suburbs had partial infrastructural support already in existence at the time, the majority of these new residents soon found themselves living under conditions of extreme privation and hardship leading to the emergence of localised health hazards and anti-social behaviour. Although to date these areas have not been awarded official names, residents refer to them under the general title of Tyoksville or Shackville. (Frescura, 1987a)

This survey, sponsored by the Urban Foundation, concentrated upon a small section of Tyoksville, officially known as Extension 4E, which incorporated some 1071 residential stands and where the road, water and sewer reticulation had reached an advanced level of development. Although a small number of conventional houses were in the process of construction at the time of the survey, all respondents questioned were the residents of self-built shacks.

The survey set out to establish a data base across a variety of concerns including the area's demographic profile, family incomes and budget patterns. Two sections were of particular architectural interest. They included questions on the social processes of construction and the building technologies presently employed by local residents in their housing efforts as well as their future housing expectations in respect to size of dwelling, building standards and housing aesthetic.

The collated results painted an interesting picture. 82% of the families interviewed had built their present dwellings themselves. The remainder had commissioned an outside contractor to build their homes, in part or as a whole, for them. An estimated 65% of materials used in the process, most specifically timber and corrugated iron, originated from second-hand sources. Houses, on an average, were four roomed and cost about R600 each to build. Generally speaking residents were unhappy with the technical performance of their homes, but a significant proportion, nearly 40% showed a more positive and realistic approach. However they were unanimous in condemning their shacks as being cold, unhealthy, flea-infested and unable to keep out the dust and the rain. Only a small minority specifically objected to their appearance.

Residents interviewed were unanimous in their preference for a solid and conventional brick-built house. 88% of the sample considered an ideal house size to consist of four to six rooms. In the case of a four-roomed dwelling these would consist of a kitchen, a bedroom for the parents, another for the children and a multi-purpose entertainment area. Five-roomed dwellings might include either an internal bathroom or an additional children's bedroom, whilst a six-roomed unit would include both. Garaging or additional rooms for tenancy received such low priority as to be almost negligible. The preference for internal bathrooms as against external facilities was overwhelming but opinions on whether such a room should include a WC or keep it in a separate cubicle were evenly divided.

The majority of residents preferred their homes to be located either to the front or the centre of their stands. Although 55% expressed a liking for a single storey suburban cottage aesthetic, a significant number, 25% also liked the looks of the standard NE51/9 of old. Traditional and farm-style aesthetics were rejected almost outright.

Despite the fact that the majority of respondents had built their current homes, most were unwilling to be involved in a process of upgrading and self-help housing. However this was not seen as an indication of apathy on their part but rather as a reflection of their aspirations towards more solidly built housing and their unfamiliarity with the technology concerned.

THE TIMBER HOUSING CASE STUDY

This study arose as the result of grievances expressed collectively by a group of moto-car assembly workers, all residents of KwaNobuhle near Uitenhage, with the quality of housing provided them by a particular contractor. This report was requested by the Port Elizabeth Legal Resource Centre whose brief it was to bring legal action against the builder and Building Society concerned. (Frescura, 1987b)

Following a preliminary meeting with the client's representative committee it was established that the builder concerned had offered different families dwellings with an area approximately 67 sq. metres in size, at a price which varied between R16,500 and R19,500 each. The technology used was a basic timber-framed structure clad externally with chipboard and internally in gypsum board. Roofing was in Canalith 'B' sheeting with the ceilings being glued to their underside. The whole frame was bolted to a 100 mm concrete raft slab. Doors were of standard type but windows were self-made by the builder and had no reveals. The clients were exceedingly dissatisfied with the technical performance of their homes which had shown a number of major flaws inherent to their design and detailing in the brief nine months since occupation. They also claimed that their houses did not match their expectations nor the promises made by the builder.

It soon became apparent that the client's problems would not be simple to resolve. These were complicated further by a number of other factors. It appeared for example that no contracts had ever been signed with the builder; that the clients had seen no drawings or specifications of the structures they were expected to buy; that they had signed no financial release forms with the building society; and that various families had been charged differing amounts, according to what work subsidy they qualified under, for exactly the same house. When a set of plans was eventually discovered (from one of the clients who had stolen it from the builder's motor vehicle!) it was found to be sketchy, inadequately detailed, little annotated and partly drawn in freehand.

The builder, the housing officer at Volkswagen (SA), the Municipality and the building society were all contacted in their turn. The first refused to return all calls and within two weeks had moved back to the Transvaal where he has since been traced; the others denied any liability in the matter giving a variety of excuses. However when the manager of the local building society was confronted with a number of irregularities which had taken place contrary to his firm's established business procedures, he hedged and claimed that third world housing required new methods of funding and administration. It is my sad duty to report that this person tragically took his own life within 24 hours of this conversation.

In view of the fact that these houses were (conservatively) valued by a quantity surveyor at R10,500 each and that they sold for an average of R18,000, the total contract price on fifty units must have involved R900,000 of which close to R400,000 was straight profit. In view of the circumstances involved, the technology used and the abuses discovered there can be little doubt that the clients concerned had been subjected to a deliberate and cynical process of exploitation which had left them with houses little better than shacks and a purchase agreement which would take most of them close to a lifetime to settle. Fortunately the building society concerned, faced with legal action and a massive bond repayment boycott from other residents of KwaNobuhle, has now resolved to provide relief and adequate compensation to the clients as a whole.

CONCLUSIONS

Taken as a whole these case studies provide some important architectural pointers to the realities and processes involved in the housing of newly urbanised communities in Southern Africa. It is clear, for example, that in spite of being faced with severe financial limitations, the communities concerned have high expectations of any housing provided for them on a straight consumer basis. On the other hand it is equally clear that the majority of people surveyed rejected equally self-help, sweat equity and dwellings built in a variety of alternative technologies. Their preference for solidly built brick or block-and-mortar structures having a conventional urban aesthetic is strongly indicative of a client body who realises its own financial constraints and is determined to get the maximum value for its money. It is also a mirror to the political realities of this country, where the demands of a well-housed bourgeois have always taken precedence over the shacks of the urban proletariat. In these terms it must be realised that a solidly-built, well-finished house is not the reflection of black aspirations towards "white-ness", it is a symbol of land tenure in a community which, for the past four generations, has become used to being moved from pillar to post at the whim of a bureaucracy obsessed with social engineering. It is also a statement by a people who, for the past century, have invested their land and labour in an unequal partnership with white technical know-how and who now want this inequality to be redressed.

The case study of the motor-car assembly workers also brings into question the role currently being played by both the private sector and the building societies in the housing process. The shortage of certain types of housing in our urban areas since the 1950's has always ensured that the awarding of building contracts and the allocation of dwellings has invariably been tainted with a degree of corruption. However, since the government has opened up the field to the private sector, the opportunities for such enterprise has multiplied ten-fold. A number of senior personnel and officials associated with the provision of housing in this country recently expressed private concerns that this area is rapidly becoming the happy hunting ground of unscrupulous entrepreneurs with a carpet-bagging philosophy. This has been most particularly true in regions where controls are most relaxed, such as the newly-emergent black municipalities and South Africa's so-called homeland states. Another curious aspect of big business involvement in black housing is the fact that many large building concerns operate in black areas under the guise of subsidiary companies with different names. The reasons for this can only be the subject of speculation.

In this respect a critical look should also be taken at the workings of financial institutions such as building societies and banks. While it is true that their role is to lend money for the purpose of housing, their reluctance to enforce realistic retention figures both hampers the work of architects and fails to safeguard their clients' - and hence their own - interests. Also, while it is true that housing has now become one of this country's major social issues, their eagerness to adopt a mantle of social responsibility should be tempered by the realities and problems of the building industries: poor craftsmanship, rogue builders, insolvencies and unenforceable product warranties. It is true that housing newly urbanised communities requires the creation of new methods of funding and administration. However, it is equally true that financial institutions are confronted with a critical and demanding clientele whose aspirations are as bourgeois and as middle class as any they have encountered in previous eras. Their contribution to housing, therefore, must be guided by the consideration that they have an additional responsibility to protect the rights of their client body.

POSTSCRIPT

This article was published in 1988 under the title of Architects, Sociologists and Carpet-Baggers: A Review of Some Housing in the Eastern Cape (ARCHITECTURE SA, July/August 1988. 44-45), and was a distillation of the following housing reports,

- Motherwell Housing Survey. FRESCURA, Franco and RIORDAN, Rory. Port Elizabeth: Builder's Warehouse, March 1986.

- Report on House Williams, Erf 950, Mondile Street, KwaNobuhle, and Twenty-nine Others. Port Elizabeth: Legal Resources Centre, October 1987.

- A Survey of Squatter Housing in KwaNobuhle. Port Elizabeth: Department of Architecture, UPE, 1987.

- Tyoksville Housing Survey: Preliminary Report. Port Elizabeth: Department of Architecture, UPE, 1987.

- Investigation Conducted into the Provision of Housing in Portions of Motherwell NU5, Port Elizabeth, between February 1988 and July 1990. Port Elizabeth: The Archetype Press, 1992.

- Port Elizabeth – An Abridged History of the Apartheid City. Port Elizabeth: IDASA, 1992.

Because many of the slides are no longer available, the illustrations included are not necessarily those that appeared in the original text. One of the reports quoted above, “Investigation Conducted into the Provision of Housing in Portions of Motherwell NU5, Port Elizabeth, between February 1988 and July 1990” appears more fully elsewhere on this site.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

FRESCURA, Franco. 1985. Major Developments in the Rural Indigenous Architecture of Southern Africa of the Post-Difaqane Period. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

1987a. A Survey of Squatter Housing in KwaNobuhle Ext.4C, also known as Tyoksville. Port Elizabeth: UPE.

1987b. Report on House Williams, Erf 950, Mondile Street, KwaNobuhle, and Twentynine Others. Research Report, Department of Architecture, University of Port Elizabeth, October 1987.

FRESCURA, Franco and RIORDAN, Rory. 1986. Motherwell Housing Survey. Port Elizabeth: Builder's Warehouse.

FRESCURA, Franco and VOLPE, Stephanie. 1988. Bisho: A Post Modernist Mirage. Architecture SA, May/June 1988. 42

GALLAGHER ARUP SAMSON INC. 1987. 538 Houses in the Winterveld. Motlhatlhana, March 1988. 26-27

HARDIE, Graham John. 1980. Tswana Design and House Settlement: Continuity and Change in Expressive Space. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Boston Graduate School.

LAZENBY, Michael. Editor. 1977. Housing People. Johannesburg: Donker.

MILLS, Glen. 1985. An Inquiry into the Structure and Function of Settlement Space in Northern Namibia. Architecture SA, January/February and March/April 1985.

SCHLEMMER, Lawrence and MOLLER, Valerie. 1982. Black Housing in South Africa. Energos, No 7, 1982. 3-37.