This Day in History: November 25, 1981

Additional Date: November 25, 1981

The armed mercenaries entered the Seychelles disguised as a beer-drinking tourist party, "The Ancient Order of Froth-Blowers." Hoare's objective was to return to power ex-President James Mancham, 49, a pro-Western leader who was deposed by René in a 1977 coup.

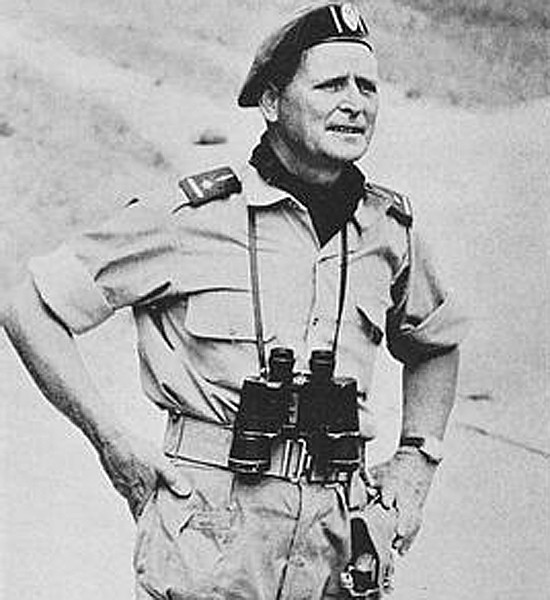

The raid was led by Colonel Thomas Michael ("Mad Mike") Hoare, who gained notoriety as a mercenary in the Congo during the 1960s. The 1978 film, "Wild Geese" is loosely inspired by Hoare's adventures, and he is the author of several books that recount his swashbuckling exploits.

But the Seychelles operation failed when a Mahé airport customs inspector found a weapon hidden in a Froth-Blower's luggage. A gunfight broke out at the airport, in which one mercenary was killed and several others wounded. Desperate to escape, the raiders fought their way to the control tower, guided an incoming Air India 707 to a landing and commandeered the plane. They forced the Air India pilot to fly them 2,500 miles across the Indian Ocean to Durban.

International suspicions pointed almost immediately to the South African government, who opposed Renee's socialist's regime and were already active in destabilizing other leftist governments in Southern Africa. These suspicions seemed substantiated by the casual manner in which the South African government dealt with the hijackers. Instead of extraditing them to Seychelles where they would be tried for treason, or charging them with hijacking, the South African government opted to unconditionally free 39 of the 44 mercenaries and charge the leaders, including Hoare, with lesser crimes.

International outcry was immediate, forcing the government to re-think their response to the incident. Several nations warned that South Africa could be struck from air-travel routings unless Pretoria enforced international agreements against harboring of air hijackers. The government then brought hijacking charges against all 43 of the escaped mercenaries.

After a five-month trial Judge Neville James found 42 of the mercenaries guilty of airplane hijacking and sentenced Hoare to ten years in prison. His fellow raiders were given from six months to five years, and the judge later reduced most to six months.

Throughout the trial Hoare insisted that his operation had the blessing of the South African government. "I see South Africa as the bastion of civilization in an Africa subjected to a total Communist onslaught," he said. "I foresee myself in the forefront of this fight for our very existence." Indeed, more than half of the convicted mercenaries had been members of either the South African Defense Force or the army reserve.

In 1998 the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission ruled that the South African Government was responsible for the attack.