One of the key instruments used by the apartheid government to neutralise political dissent was the State of Emergency (SOE). In periods when the government faced unprecedented internal revolt – both in 1960 and in the 1980s – an Emergency was declared. This resulted in the detention of thousands of political activists within a short space of time, and an exodus of some to a life in exile.

In 1960, for the first time, the government was faced with a widespread revolt against passes gathering pace at an alarming rate. The revolt threatened to derail plans to implement apartheid measures and thus consolidate white minority rule. In the 1980s increasing internal unrest, political violence and attacks – particularly uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the armed wing of the African National Congress (ANC) – precipitated the declaration of the State of Emergency.

State of Emergency in 1960

“In 1960 the emergency was imposed so that the state could implement its apartheid policies,” reads an article which appeared in Isizwe (1986). The article also illustrates how the Nationalist Party (NP) had a clear political strategy to consolidate the apartheid laws – which were rejected by the majority of the people of South Africa. These policies included the development of Bantustans, the imposition of influx control through enforcing pass laws, the implementation of Bantu education, and forced removals under the Group Areas Act.

The massacre of unarmed protestors at Sharpeville, near Vereeniging in the province of Transvaal, on 21 March 1960, was a turning point in the history of South Africa. What began as a peaceful march by Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC) supporters to the police station – in protest against the pass laws and calling for a minimum monthly wage of 35 pounds – was turned into a massacre when police fired at the protestors, killing 69 people and injuring 180.

In response to this state brutality, strikes broke out and stayaways ensued, forcing the government to declare a State of Emergency. On 30 March 1960, the government declared a State of Emergency in 83 magisterial districts – this was the first state of emergency declared by the Apartheid State. The government then moved to pass the Unlawful Organisations Act on 7 April 1960, which banned both the ANC and the PAC. Consequently, there was a sharp rise in the number of people detained: by 6 May 1960 the government revealed in Parliament that 18,000 persons had been arrested and detained since the proclamation of the Emergency. Detainees were held without access to lawyers and family, at times in solitary confinement. Most detainees were released after spending one or two months in jail, but about 400 remained in jails across the country until the Emergency was lifted.

In addition, Chief Albert Luthuli and Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe, leaders of the ANC and PAC respectively, were detained. With the crackdown on political activity spreading throughout the country, leading political figures from both movements skipped the country and went into exile. ANC leader Oliver Tambo left the country in March 1960, and that same month the PAC’s Nana Mahomo and Peter Molotsi crossed the border into Bechuanaland.

After the Sharpeville massacre the international community protested against the brutality of the South African government. The United Nations condemned the apartheid government, and Resolution 134 was adopted on 1 April 1960 to show disapproval of “the situation arising out of the large-scale killings of unarmed and peaceful demonstrators against racial discrimination and segregation in the Union of South Africa”.

Following their bannings, in 1961 the PAC and ANC launched their armed wings, Poqo and MK respectively, to commence the armed struggle. In the MK manifesto of December 1961, the ANC made reference to the State of Emergency as “virtual martial law”. Faced with the threat of an armed revolt, the government introduced a number of security laws in the 1960s, including the General Laws Amendment Act (90 day detention law) and later the Sabotage Act, which was specifically aimed at the two underground movements, MK and Poqo.

The 1970s saw the emergence of the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM), which dominated political resistance until Steve Biko, who was a leading figure, died in detention and the state banned 18 BCM-aligned organisation in 1977. The revolt of June 16, 1976 saw students marching through the streets of Soweto in protest against the directive from the education department that Afrikaans should be the language of instruction at black secondary schools. Police opened fire on the pupils, who torched government-linked buildings and buses and stoned cars. The killing of numerous BCM anti-apartheid activists precipitated international hostility towards the apartheid regime.

State of Emergency in the 1980s

Image from Digital Innovation South Africa (DISA)

Image from Digital Innovation South Africa (DISA)

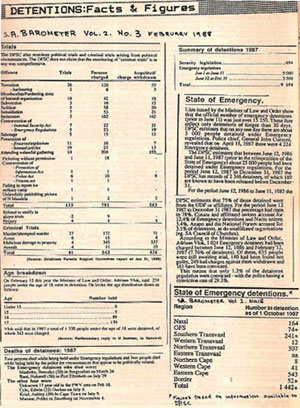

In contrast to the Emergency declared in 1960, the 1985 and 1986 crackdown resulted in more arrests than ever before. On 20 July 1985, President PW Botha declared a state of emergency in 36 of the country’s 260 magisterial districts. Within the first six months of the Emergency, 575 people were killed in political violence – more than half killed by the police. Under the provisions of the Emergency, organisations could be banned and meetings prohibited; the Commissioner of Police could impose restrictions on media coverage of the Emergency; and the names of detained people could not be disclosed. On 5 March 1986 Botha announced that he would lift the Emergency, and on 7 March the announcement was made law.

The lifting of the Emergency was short-lived as on 12 June 1986 – four days before the 10th Anniversary of the Soweto Uprising – the government declared a country-wide State of Emergency. The crackdown differed from the 1985 Emergency in that it covered the entire national space and was more rigorous: political funerals were restricted, curfews were imposed, certain indoor gatherings were banned and news crews with television cameras were banned from filming in areas where there was political unrest.

This in essence prevented both national and international news coverage of police brutality and the government’s faltering attempts to contain the wave of social unrest. An estimated 26,000 people were detained between June 1986 and June 1987.

As the process of transition from apartheid to democracy began, with negotiations between the government and ANC commencing in earnest, the NP-led government moved to normalise the political climate. On 7 June 1990, President FW de Klerk announced at a joint sitting of parliament that he would be lifting the four-year-old State of Emergency in all provinces except Natal. The Emergency was duly lifted on 8 June 1990. Four months later, in October 1990, De Klerk announced the lifting of the four-year State of Emergency in Natal – political violence between the ANC and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) ensured that Natal was the last province to have the restrictions lifted.

However, on 31 March 1994, Natal once more came under a State of Emergency – in an attempt to contain political violence in the province. What precipitated the declaration of the Emergency was the increase in clashes between IFP and ANC supporters as vigorous campaigning for the first democratic elections gathered momentum. While white rightwing politicians and Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi opposed the government action, the ANC responded positively. Under the Emergency regulations, soldiers had the power to ban marches, detain people and seize weapons, although campaigning for the impending election was permitted.

Conclusion

The State of Emergency was a draconian instrument used by the apartheid government to detain people in large numbers while bypassing legal avenues. People could be arrested and held in undisclosed locations, while others could be killed without the police or other state security apparatuses being held to account. Statisics reveal that there was a correlation between, on the one hand, increases in detention, deaths in detention, resort to exile, and the declaration of a State of Emergency on the other. Despite heavy-handed crackdowns on political dissent throughout the apartheid period, people continued to fight against apartheid. With sustained internal unrest and international pressure, the apartheid system unravelled, to usher in a new era of democratic rule in South Africa.

Image from “SA press clips supplement “the State of emergency: June 1987-June 1988”

Image from “SA press clips supplement “the State of emergency: June 1987-June 1988”