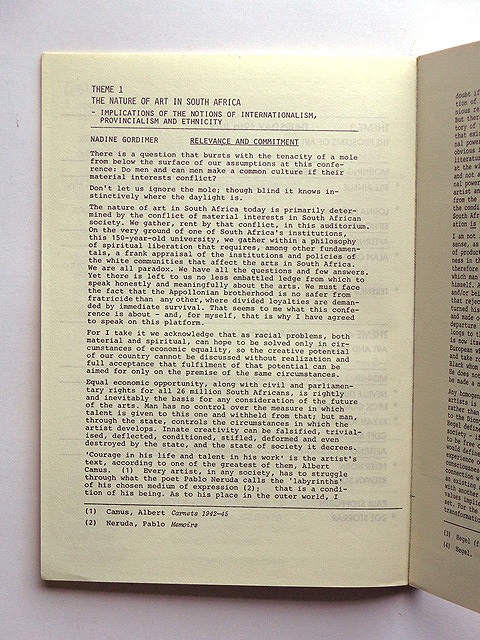

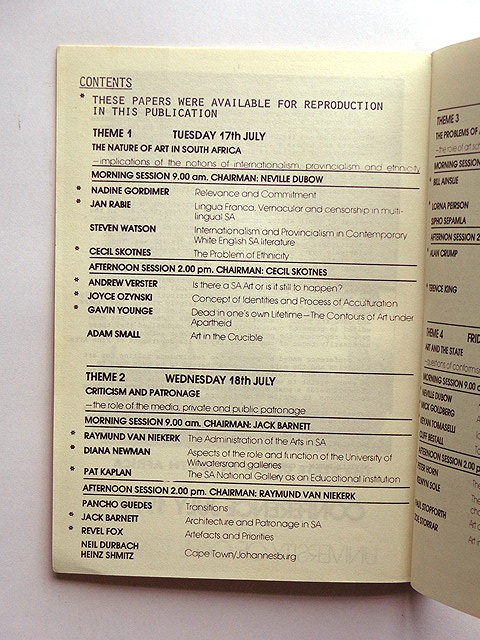

Held at the University of Cape Town from 16-20 July 1979, The State of Art in South Africa Conference was chaired by Neville Dubow, then head of the Michaelis School of Art. It was the first multi-disciplinary gathering of artists, educators, museum professionals, intellectuals, academics and students that addressed the ethical responsibilities of the artist with regard to the Apartheid State, calling for recognition of state control and the agency of the artist as either its functionary or its revolutionary opponent.

Art was postulated as necessarily political, and that likewise, it has a direct relation to the community it emerges from, particularly if that community is built upon the oppression of others. The role of the artist was recast as that of cultural worker, as someone committed to the anti-apartheid struggle. Part of this newfound delineation of roles was the active refusal of the state through boycotting the operation of art as a tool of cultural diplomacy and respectability forged under, and essentially an extension of, Apartheid propaganda and Afrikaner Nationalism. From the Conference Proceedings it was noted that “…it is the responsibility of each artist to work as diligently as possible to effect change towards a post apartheid society. It urges artists to refuse participation in state sponsored exhibitions until such time as moves are made to implement the above mentioned change.”[1] Part of this refusal was the call towards non-racial art education by Bill Ainslie on the final day of the conference – White artists would refuse to show their work abroad until all state-funded art institutions were open to Black as well as White students, and furthermore that Black artists would be supported to attend art training at universities through bursaries.

John Peffer notes how most Black artists “boycotted the event for its outward appearance of being a ‘white’ gathering at an elitist institution”, and this turnout was lamented by those who did attend the conference.[2] In fact, the first day of the conference became a debate on why no Black artists were scheduled to present papers at a gathering trying to make sense of the civic duties of art in South Africa. Artist Gavin Younge stated in this regard “I know that black artists were invited. What I have heard is there is the feeling that nothing important would change as a result of the conference. Someone must be laughing somewhere to hear that black artists want to remain separate from white artists.”[3] What became apparent was that the context of the conference alienated a large number of potential Black contributions, and that another setting would be required for a more representative gathering of cultural workers. In this light the Culture and Resistance Festival held by the Medu Arts Ensemble in Gaborone, Botswana in July 1982, would become that space in which exiled and Black artists could also reflect on the powers of art as political tool.

Despite the absenteeism and negations of The State of Art in South Africa Conference, it remains a pivotal precedent to subsequent conferences and festivals, and her

End Notes

[1] The State of Art in South Africa. Conference Proceedings. Cape Town: University of Cape Town, 1979, page 159 ↵

[2] John Peffer. Art and the End of Apartheid, University of Minnesota Press: London & Minneapolis, 2009, page 93 ↵

[3] Younge cited in Sue Williamson. Resistance Art In South Africa, David Phillip Publishers: Cape Town, 1989, page 9 ↵