In 1975, Peter Johnson, joined the ranks of the uMkhonto we Sizwe and disappeared into exile. Nearly a decade later, on the 26 October 1984, Johnson, now known as MK member Tom Livingstone Gaza, died during a guerrilla skirmish just outside the borders of Bophuthatswana. Years later, Ms Garland Andreas, one of Peter Johnson’s sisters, approached the Truth and Reconciliation Commission asking them to help her find his remains.

The investigation that followed proved to be a considerably difficult one for the Missing Person Task Team, an organisation set up by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to help find people who went missing for political reasons; the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (Equipo Argentino de Antropología Forense, EAAF), a non-governmental, non-profit scientific organisation that uses forensic sciences to investigate human rights violations all over the world; and the local investigators that helped track him down.

The search for Peter Johnson’s remains began in 1994, when Petronella, another of Peter Johnson’s sisters, received word via newspaper (The Argus) that former exile, Henry Abrahams, had been looking for Johnson’s sisters. In the meeting that followed, Abrahams, with the help of MK member Mikkie Xayiya, explained what had happened to Peter, 10 years prior. [i] Two years later, on the 20 July 1996, Ms Garland, approached the Truth and Reconciliation Commission with information about her brother, asking them to help find his remains. [ii] According to Ms Garland, Peter Johnson had been sent to Robben Island in 1969 for non-political reasons. Once there, he became politicized by fellow political prisoners. This happened at a time when Piet Pelser, the Minister of Justice and Prisons, denied political prisoners stayed on Robben Island, aside from former leader of the Pan African Congress (PAC), Robert Sobukwe.

In order to begin an enquiry, the first thing investigators needed to prove was that Johnson was of political importance. The easiest way to do this was for investigators to search through more than six thousand pictures in the Security Police album and put Peter Johnson’s face to his political status. This proved to be unsuccessful, Johnson could not be found. The search was not in vain, however, as an image of Mikkie Sivuyile Macmillan Xayiya, the same man Henry Abrahams had taken to meet up with Johnson’s sisters, was found. Xayiya, had been with Johnson and fellow deceased MK colleague Karabo Madiba, on the day of their deaths. [iii]

Portrait of Mikkie Xayiya as a young man. This photograph was found within the Security Police Albums and later moved into Peter Johnson and Karabo Madiba: Missing Person’s Task Team Report, 2007

Portrait of Mikkie Xayiya as a young man. This photograph was found within the Security Police Albums and later moved into Peter Johnson and Karabo Madiba: Missing Person’s Task Team Report, 2007

According to Xayiya, the event ultimately started with Karabo Madiba, who had left South Africa in 1980 having been arrested and charged in 1979 under the Internal Security Act, guiding Johnson and himself safely through the Mafikeng area. The men arrived at Ms Agnes Khubeka’s house, Karabo’s sister, but following some tension over their arrival they found themselves forced to go back on the run.

The taxi in which they escaped dropped them off at Cook’s Lake, an area on the outskirts of the Mafikeng. For Peter and Karabo, death came next. Whilst traveling through the area, security forces arrived with dogs. Xayiya recalls that at that moment Peter Johnson announced he would not be captured by the police and shot himself in the head. Following Johnson’s death, Karabo and Xayiya split up. Although he attempted to hide, Xayiya was caught by police. He was subsequently charged with terrorism in the Rustenburg magistrate’s court and sentenced to imprisonment on Robben Island, until his release in the 1990s. [iv]

The remaining details of the event were rediscovered when investigators found two inquest dockets, Mafikeng GO 18/84 and GO 19/84, recalling the encounter from the police’s perspective. [v] On receiving top secret information, the Commander of the Bophutatswana police’s Task Force in Mafikeng immediately began a search for potential armed terrorists entering the Cook’s Lake area. Two hours into the search, he heard a gunshot coming from a south-easterly direction. On reaching the location of the gunshot, the Captain happened upon an unidentified body; later identified as Peter Johnson. In Johnson’s right hand lay a Makarov pistol. Meanwhile, a group of policemen, also in search of the suspected terrorists, were confronted by Karabo Madiba as he was allegedly about to throw a grenade at them. In self-defence, the police shot Karabo, causing the grenade to go off beside him, resulting in his death.

With a story in place that connected Johnson and his colleagues to political struggle, investigators next step was to find their burial site. This proved considerably difficult. At first, investigators followed in the footsteps of Mrs Hilda Madiba, whom they had interviewed earlier in relation to the case. [vi] Mrs Madiba had long ago begun a search for her son, Karabo. Through the help of a friend, who worked for the Bophutatswana government, she had apparently located his corpse at Victoria Hospital. However, after she had identified him through his birthmark, police took him and buried him in an undisclosed location. This was corroborated when the missing person’s task team investigated the 1984 mortuary registers at the Bophelong Hospital in Mafikeng and found a docket retrieved from the police indicating that Karabo and Johnson may have been taken to Victoria Hospital in the Mafikeng. [vii] Unfortunately, however, no substantial records of the two men were found there. While there was the record of the doctor who performed the post-mortem on the remains, he could not recall which burial agency had taken the bodies away.

With so many vital pieces of the puzzle missing, investigators were forced to turn to the difficult method of finding Karabo and Johnson’s remains through process of elimination. They started by researching which cemeteries were operational in the 1980s. This led them to believe that Mafikeng, Mmabatho cemetery was the most likely candidate for the graves they sought.

Mafikeng, Mmabatho Cemetery. Picture by Daan Prinsloo Image source

Mafikeng, Mmabatho Cemetery. Picture by Daan Prinsloo Image source

One promising lead led investigators to Barolong Funeral Undertakers. Barolong had handled all cases of pauper burial in Mmabatho cemetery in the period Johnson and Karabo died. [viii] Again, however, investigators were left without much as the funeral home had no records of the two men. What investigators did discover during this process, however, was that the Protective Services section in the Municipality administered cemetery and burial records to the Traffic and Fire Department. In the mid-1990s, the Traffic and Fire Department transferred these documents to the Community Services department. In the course of the transfer, it appears the records disappeared. [ix]

With barely any information to go on, the Missing Persons Task Team approached the air force, asking them to help map the cemetery for potential burial sites of Johnson and Karabo. The photographs proved difficult to work with. In light of this disappointment but unwilling to give up, the team undertook the tedious task of manually mapping the cemetery. After a long haul, some possible success was reached when a number of unmarked graves proved to be potential sites for the two deceased.

Thus began a massive forensic examination conducted on Mmabatho cemetery between the 20 and 23 June 2006, by the Missing Persons Task Team, the EAAF, and two other local experts. Over a period of 72 hours and after some further elimination tactics, the grave site 595 was ruled as the likely site of the two deceased. [x] With only one grave a potential match, investigators speculated that the bodies were buried on top of one another; a common practice in pauper burials, although a claim that the cemetery denied was a practice they conducted. Although disappointed that another grave site was not a match, investigators decided that grave site 595 should at least be exhumed. A few weeks later, on the 4 July 2006, grave 595 was opened and excavated. [xi] Once exhumed, investigators final doubts were put to rest as their assumptions were proven correct: two men matching Peter Johnson and Karabo Madiba had indeed been buried on top of one another.

In order to confirm beyond doubt that investigators were correct, the men’s remains were sent to the Cultural History Museum in Tshwane for examination and identification. [xii] Upon analysis, a forensic anthropologist confirmed that the skeletal remains were consistent with Peter Johnson and Karabo Madiba’s. A little later, further confirmation came from the Human Identification Laboratory at the Biotechnology Department at the University of the Western Cape, when DNA testing confirmed a match. [xiii] In light of this final confirmation, investigators, family, friends and comrades were finally relieved of their uncertainty over Peter Johnson’s final resting place. With help from African National Congress (ANC) members and others linked to Peter Johnson’s case, his story could finally be stitched together and told to the public.

Peter Johnson’s Story

Peter Johnson was born in Oakdale, Western Cape on the 19 September 1950, the second child of five siblings. He grew up in Bellville-South after his family forfeited their home during Apartheid. His sisters were all sent to orphanages, but he was sent away to live with Nazeem Mullins in Canterbury Street, Elsies’ River. Life for Johnson was not easy or free of trouble.

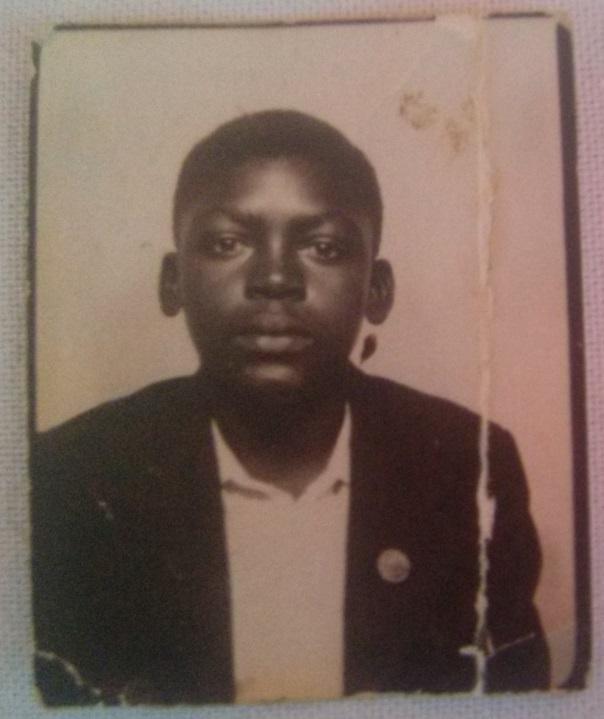

Portrait of a young Peter Johnson. Found in Peter Johnson and Karabo Madiba: Missing Person’s Task Team Report, 2007

Portrait of a young Peter Johnson. Found in Peter Johnson and Karabo Madiba: Missing Person’s Task Team Report, 2007

In 1969, Johnson was imprisoned for five years on Robben Island for undisclosed common law crime. It was here that he learnt about the political climate of South Africa from the political prisoners who had been there for years. When his sentence was complete, Johnson decided to join fellow political members in exile.

Johnson entered Robben Island at a time of powerful resistance against the Apartheid government. In the 1960s, common law prisoners were held together with political prisoners on Robben Island. [xiv] In 1963 and 1964 large numbers of political prisoners began to populate the Island. In this arena, political prisoners kept up to date with Marxist thinking, and contemporary theories concerning Black Consciousness and liberation. In 1967, two years before Johnson’s arrival, there were over 1000 political prisoners, most of them from the African National Congress and the Pan Africanist Congress. [xv]

In the 1970s, a wave of new resistance was led by Black Conscious activists. The resistance was supported by many Black school and university students and workers. These included the Soweto Student Representative Council (SSRC), the South African Student Movement (SASM) and the Black Parents Committee (BPC). During Johnson’s exile; he received military training at Odessa in the Soviet Union. He later commanded and controlled the town camps in Angola, Quibaxe and Pango. In 1979, township-based regional organizations were established, such as the Soweto Civic Association and the Port Elizabeth Black Civic Organisation, as well as the Congress of South African Students (COSAS), which organized Black students. A revolution in politics was occurring, and Johnson was preparing for it. [xvi]

The shift in leadership from Prime Minister B.J Vorster to P.W Botha was the final push needed for Black protests to turn into full blown insurrection. When P.W Botha took office, he intended for the Apartheid government to be reformed, which implied to anti-Apartheid protestors that White rule was to be re-structured and not ended. [xvii] In 1984, Peter Johnson joined Joe Slovo, then chief of staff of umKhonto we Sizwe, and returned to South Africa as the commander of a guerrilla unit. This planned assault on Baphutatwana fell in line with a larger insurrection gripping South Africa between 1984 and 1986. [xviii] For Frans L. Buntman, this insurrection period was integral in the advancement of structures of governance within the Black community. These insurrections put the Apartheid regime on the defensive and undermined their reform programs, ultimately helping both to delegitimize the state on a global scale, and to shake the oppressive minority rule. [xix]

Although left missing for decades, Johnson was never forgotten by those who loved him. Following the recovery of his mortal remains, Johnson’s legacy was remembered by his local Bellville community, who feted him as a community hero, with pictures of him appearing in newspapers, pamphlets and brochures. [xx] Like so many struggle figures who were killed, his historical contribution is to have been part of a greater insurrection that pushed South Africa into a new phase of political governance. [xxi]

The photograph of Peter Johnson situated alongside a picture of MK/ANC creating a connection between respecting the disappeared by voting for the ANC. Found in Peter Johnson and Karabo Madiba: Missing Person's Task Team Report, 2007

The photograph of Peter Johnson situated alongside a picture of MK/ANC creating a connection between respecting the disappeared by voting for the ANC. Found in Peter Johnson and Karabo Madiba: Missing Person's Task Team Report, 2007

In the absence and fragmentation of physical evidence, Johnson’s story relied heavily on accounts by friends, family, comrades and political affiliations. Without the aid of the MPTT, EAAF, and the local investigation teams, it is a story that may have never resurfaced. [xxii] In the pages of Sechaba, an ANC publication, Johnson’s suicide is remembered as a sacrifice made to protect military plans meant to liberate the people from the Apartheid state. An extract in Sechaba, referring to Johnson, reads: “like all wars, the war against apartheid produced its cowards, traitors and heroes,” whilst the cowards are forgotten the heroes are honoured.

Endnotes

[i] Missing Persons Task Team. Peter Johnson and Karabo Madiba. Priority Crime Litigation Unity: National Prosecuting authority, Cape Town: Missing Persons Task Team, 2007, p. 5. ↵

[ii] Missing Persons Task Team. Peter Johnson and Karabo Madiba, p. 5. ↵

[iii] See, Smillie, Shaun. ‘Now mother and son can finally rest’, The Star, 19 October 2006. ↵

[iv] Missing Persons Task Team. Peter Johnson and Karabo Madiba, p. 3. ↵

[v] Missing Persons Task Team. Peter Johnson and Karabo Madiba, p. 6. ↵

[vi] Missing Persons Task Team. Peter Johnson and Karabo Madiba, p. 4. ↵

[vii]Missing Persons Task Team. Peter Johnson and Karabo Madiba, p. 6. ↵

[viii] Missing Persons Task Team. Peter Johnson and Karabo Madiba, p. 8. ↵

[ix] Missing Persons Task Team. Peter Johnson and Karabo Madiba, p. 8. ↵

[x] Missing Persons Task Team. Peter Johnson and Karabo Madiba, p.9 ↵

[xi] Missing Persons Task Team. Peter Johnson and Karabo Madiba, p. 10 ↵

[xii] Missing Persons Task Team. Peter Johnson and Karabo Madiba, p. 11 ↵

[xiii] Missing Persons Task Team. Peter Johnson and Karabo Madiba, p. 12. ↵

[xiv] Dick, Archie L. "Blood from stones: Censorship and the reading practices of South African Political Prisoners, 1960-1990." Library History (University of Pretoria), 2008, p. 3. ↵

[xv] Buntman, Fran Lisa. Robben Island and Prisoner Resistance to Apartheid. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003, p. 19. ↵

[xvi] Buntman, Fran Lisa. Robben Island and Prisoner Resistance to Apartheid, p. 21. ↵

[xvii] Buntman, Fran Lisa. Robben Island and Prisoner Resistance to Apartheid, pp. 23-4. ↵

[xviii] Buntman, Fran Lisa. Robben Island and Prisoner Resistance to Apartheid, p. 24. ↵

[xix] Buntman, Fran Lisa. Robben Island and Prisoner Resistance to Apartheid, p. 24. ↵

[xx] See, Gosling, Melanie. ‘Apartheid fighters to get a hero’s welcome’, Cape Times, 10 May 2007, p. 4. ↵

[xxi] See, Smillie, Shaun. ‘Suspected remains of cadres taken from graves’, The Star, 5 July 2006. ↵

[xxii] See, Mangxamba, Sivuyile. ’Final rest for apartheid victims’, Cape Argus, 10 May 2007, p. 3. ↵