The apartheid era was characterised by different resistances such as the Sharpeville massacre, Vaal and the East Rand in 1985 and Soweto uprising of 1976. The apartheid era ended in 1994, and people hoped that South Africa would not be the same anymore and that there would not be any massacres again. An old era ended and the new started. Mass demonstrations and protests happened in the democratic context where citizens rely heavily on the government to protect them, as well as to promote and protect human rights in general. On 16 August 2012, democratic South Africa witnessed what is now called the Marikana massacre, when a large number of miners were killed by the police.

South Africa is seen as the protest capital of the world, with one of the highest rates of public and labour protests in the world. The rate of protests has been on the increasse since the advent of democracy. Though, the current wave of protests stretches back to the 1970s and 1980s, the rate of protests rose dramatically and most of the protests took place across the country. People’s level of discontent around the government’s poor service delivery, poor wages and poor working conditions at workplaces have been very high. The Marikana massacre was viewed as a violation of human Rights. There has been considerable repression of popular protests. The most common reasons for protests are grievances around delivery of services such as houses, water, electricity, land and other public infrastructure, as well as minimum wages and good working conditions for workers. Informal settlements have been at the forefront of service delivery protests as residents demand houses and basic services.

The country has witnessed numerous labour protests since the beginning of democracy. Some protests were initiated by trade union movements and others were initiated by the workers themselves.

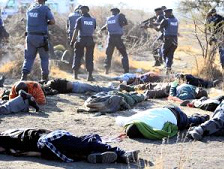

A major protest that resulted in the killing of protestors was the 2012 Marikana protest by mine workers. On 16 August 2012, South African Police Service (SAPS) officers shot and killed at least 34 striking miners and injured 75 people in Marikana, North West Province, South Africa. The workers had staged a wildcat strike a few days earlier and were protesting outside the Lonmin mine when police opened fire with live ammunitions in what was called the first massacre in democratic South Africa. The strike was initiated by the mine workers themselves, mainly the rock drillers.

Shootings by SAPS Source

Shootings by SAPS Source

Rock-drill mineworkers are under-ground workers, responsible for operating a hand-held machine rock drill. They drill straight into the rock face. They were paid R4000 a month. They also do indispensable work, driving the heavy pneumatic drills deep into the quartzite rock that encases the gold and platinum. One of the reasons that caused the strike was the extreme exploitation of mineworkers by miner owners to reduce labour costs. Rock-drillers were expected to perform quickly and efficiently, while at the same time having to accept the lowest of wages. Most of them were not unionised and they were migrant seasonal workers. However, a new union, Association of mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU) was already recruiting them. The Marikana massacre sparked anger across South Africa.

The Marikana massacre reminded the local and international community’s of the 1960 Sharpeville massacre when apartheid-era police officers injured 180 black Africans and killed 69 when the police opened fire on demonstrators in the township of Sharpeville protesting against the government’s pass laws, 1976 Soweto uprisings, 1980s protests when many of South Africa Black people were killed. Prior to the killing of 34 mine workers, At least 10 more people died in other clashes in the region. The picture that seemed to emerge was that the tragedy was preventable and police may have been instigated by Lonmin executives and/or government to act violently against the protesters.

The Marikana massacre pointed to the involvement of police officers in acts of brutality against black male workers in order to bring an end to the Marikana strike. The massacre was also an emotional reminder that police brutality is still happening in post-apartheid South Africa.

Similarly, one of the public protests that resulted in death of a protestor which sparked anger across the country was the killing of Andries Tatane, a 33 year old man, by the South African police officials. On 13 April 2011, Andries Tatane was kicked, beaten and shot twice in the chest by police officers during the service delivery protest in his hometown of Ficksburg, Free State Province.

Other mine workers survived and were arrested. They said that they were tortured and brutalised by the police. The families of mine workers who were killed in the Marikana strike struggled to deal with the trauma. They were left without husbands, brothers, fathers and sons. They are also struggling in a material sense, deprived of their breadwinner’s wages and remittances. Many mine workers had families in provinces such as Eastern Cape. This in turn had an impact on access to food, as well as access to education for their children.

Rural communities, especially in the Eastern Cape, have lost people who put aside portions of their wages to buy football kits and balls for the local teams they grew up in and coached. They have lost mediators, companions, and workers who advised on issues affecting them. Churches have lost pastors and choir members. Marikana has changed families and communities across South Africa. It has certainly changed how many people see their relationship with their democratically elected government.