On 9 June 1983, three members of the armed wing of the African National Congress (ANC), uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK), were executed at the gallows in Pretoria Central Prison. Marcus Motaung, Jerry Mosololi and Simon Mogoerane were charged with treason, with alternative charges of terrorism, murder and attempted murder, among others. Despite an international campaign to save their lives, the apartheid government went ahead with the execution.

Arguably, two of the pillars that sustained the apartheid government’s rule for 46 years were racially divisive legislation, and sheer brute force. The period from the 1960s to the 1980s was punctuated by the enactment of security laws that enabled the government to arrest, detain and imprison those who fought against its racist laws. Several anti-apartheid political activists found themselves serving long prison sentences in various gaols across the country. Over and above this, the security apparatus of the government also engaged in the extra-judicial killing of anti-apartheid political activists. Incidents involving abduction, murder and death in detention – often with no recourse to a court of law – became increasingly common, particularly during periods of heightened political tension.

While illegal executions were common, the focus of this feature is on those who were sentenced to death and executed after they were brought to trial. Between 1961 and 1989, about 134 political prisoners were executed by the apartheid government at Pretoria Central Prison. Two decades in particular – the 1960s and the 1980s – witnessed many political executions. While Pretoria Central prison was the main site for executions, it was not the only facility in the country to enact these murderous acts.

The Aftermath of Sharpeville

One of the turning points in the history of South Africa was the Sharpeville Massacre on 21 March 1960, when the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) organised and led a protest against the pass laws. Police fired on the crowd of unarmed protestors, killing 69 people and injuring 180. As tension mounted, the government declared a state of emergency on 30 March 1960 and banned the ANC, PAC and the South African Communist Party (SACP). As a result, thousands of activists were detained and imprisoned, while many others fled into exile. The clampdown precipitated the launch of the armed struggle by the now banned liberation movements.

The execution of Poqo activists, 1961-1989

In 1961 the PAC launched its armed wing, Poqo, and engaged in an armed rebellion against whites and perceived government representatives. Between 1962 and 1963 Poqo activists carried out attacks against both black and white targets, particularly in the Cape and Transkei. The period between January and November 1962, in particular, saw an increase in PAC attacks. In response, the government arrested several PAC and Poqo activists – by June 1963, 3,246 members were arrested across the country and 124 accused of murder. While several were sentenced to lengthy terms on Robben Island, others were put to death. On 1 October 1963 four members of Poqo – Richard Matsapahae, Josia Mocumi, Thomas Molatblegi and Petrus Mtshole – were sentenced to death for the murder on 18 March 1963 of a Black Special Branch detective.

On 16 March 1962, Poqo activists attacked and killed Michael Livele Moyi, a policeman in Langa, and injured five others. Jim Mountain Ngantweni and Zibongile Serious Dodo were arrested in connection with Moyi’s death, and further charges were laid against Nontasi Albert Tshweni and Donker Ntsabo, who were already serving sentences for other political offences in the Eastern Cape.

All four men were hanged on 31 October 1967. Veyisile Sharps Qoba was later arrested and sentenced to death, and executed on 7 March 1968.

After the Paarl Rebellion, 400 people were arrested. Subsequently, six trials involving 75 people took place. Of these, 21 were accused of sabotage and given lengthy sentences. Lennox Madikane, Fezile Feilx Jaxa and Mxolisi Damane were sentenced to death for sabotage and executed on 1 November 1963.

Gladstone Nqulwana, already serving a 15-year sentence for sabotage for Poqo activities in the Eastern Cape, was sentenced to death on 15 June 1967 for his role in the murder of Mthobeli Nathaniel Magwaca, a municipal policeman from Langa, on 26 September 1962. Nqulwana was executed on 23 November 1967.

Poqo activities were not limited to the Cape, they extended to the Transkei, where chiefs who were seen as collaborators with the apartheid government were targeted. Activists relayed messages about operations from Langa to the Transkei. While some were successful in delivering these messages, others were apprehended by the police. On 14 October 1962, Poqo members killed one of Chief Kaizer Matanzima’s advisers, and that same month attempted to assassinate Matanzima. Two weeks later, on 29 October, Poqo activists attacked and killed a Thembu chief, Gwebindala Gqoboza. Subsequently, six members were apprehended and sentenced to death and hanged on 9 May 1963. James Mtutu Apleni, a Langa-based Poqo member who played a key role in organising attacks against Matanzima in Transkei, was arrested and sentenced to death. He was executed on 8 November 1963.

In February 1963, Poqo activists attacked and killed Norman Grobbler, his wife, two daughters – Edna and Dawn – and Derek Thompson. Following the incident, the police harassed the activists’ family members. Scores of activists were arrested and 23 were sentenced to death – of these, 15 were hanged. By 1963, Forward, a monthly publication, reported on 80 political trials of 1,105 people, 40 of whom were sentenced to death, six to life in prison.

In sum, the 1960s witnessed the imprisonment and executions of a number of PAC-linked activists. The moves devastated Poqo and the organisation was unable to revive the PAC’s armed struggle, and in its place the Azanian People’s Liberation Army (APLA) was launched in 1968. Plagued by internal power struggles, the exiled APLA remained largely ineffective until the 1980s and 1990s.

The Bethal Trial of 1979, where 18 members of the PAC were charged with treason, resulted in the death of four members who died in detention, although none were sentenced to hang. In the 1980s, Frank Rivers, a member of the PAC who was arrested in 1978 for the murder of Kranskop farmer Jacobus van Rooyen, was sentenced to death in Pietersburg (now Polokwane) in March 1982. He was granted leave to appeal, but his family did not have money to finance the appeal and he was hanged at Pretoria Central prison in 1984.

Execution of a member of the African Resistance Movement (ARM)

The banning of the liberation movements pushed the Liberal Party of South Africa (LPSA) to consider other forms of resistance. After the declaration of the state of emergency on 30 March 1960, several members of the LPSA were detained and held at the Johannesburg Fort. Ernest Wentzel, John Lang and Monty Berman played a leading role in establishing the National Committee of Liberation (NCL), which sought to use force in fighting the apartheid government. In 1964 the NCL was renamed the African Resistance Movement (ARM). Frederick John Harris, a member of the LPSA and later ARM, planted a bomb at the Johannesburg Station which exploded on 24 July, 1964, killing one person and injuring others. Harris was arrested and charged with murder and two counts of sabotage. He was sentenced to death and executed in Pretoria on 1 April 1965. Harris became the only white person to be executed for acts of sabotage against the apartheid government.

The execution of ANC and MK activists, 1961-1989

With the banning of the liberation organisations, the ANC moved to form uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK), an underground armed wing, to carry the struggle forward. On 16 December 1961 MK announced its existence with a series of explosions in various parts of the country. Following a sabotage campaign, the government arrested ANC suspects and meted out harsh prison sentences.

On 12 January 1964, Sipho Mange was shot dead – allegedly by MK operatives in Port Elizabeth. As a result, a number of MK operatives – among them Vuyisile Mini, Wilson Khayinga and Zinakile Mkhaba, Jacob Sikundla, Thompson Daweti, Charles January, Nolali Mpentse, Samuel Jonas and Daniel Ndongeni – were all arrested. Accused under the Terrorism Act of 17 counts of sabotage in the Port Elizabeth area, they were also charged with six counts under the Suppression of Communism Act.

On 16 March 1964 Mini, Khayinga and Mkhaba were sentenced to death. Their appeal against their conviction was dismissed in September and they were executed on 6 November 1964. Sikhundla was sentenced to 22 years in prison. Ndongeni, Mpentse and Jonas were tried separately on charges of murdering Mange. On 23 February 1965 they were sentenced to death, and they were executed on 23 February 1965. These were the first MK cadres to be hanged for political offences.

MK was severely crippled by the heavy-handed response of the state. Several leading members, including the high command, were jailed before the Rivonia Trial. Other political trials also resulted in the imprisonment of several ANC members and MK operatives, while others went into exile to undergo military training. Thus, throughout the 1970s, political activity remained largely underground and mostly ineffective. The South African political landscape was dominated in the 1970s by the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) and anti-apartheid student political activity. After the Soweto Uprising on 16 June 1976, hundreds of young people left the country to join the liberation movements in exile, where they received military training. Despite heightened political activity, there were no political executions between 1970 and 1978.

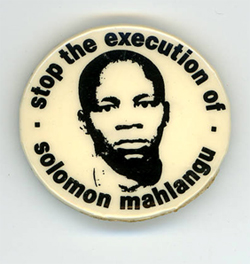

However, from 1979 into the 1980s, the situation changed as young people who had left the country in 1976 came to be deployed after receiving military training. Solomon Kalushi Mahlangu, who had joined MK and received military training outside the country, returned to the country in June 1977. Mahlangu and his comrade, Monty Motloung, were confronted by police in central Johannesburg, and two people were killed and two injured in the shoot-out that ensued. Mahlangu and Motloung were arrested, tortured and assaulted, with Motloung suffering brain damage. Mahlangu was charged with two counts of murder, two of attempted murder and several charges of sabotage under the Terrorism Act. Despite Mahlangu’s lawyers proving that it was Motloung who wielded the gun, Mahlangu was charged under the apartheid-era legal principle of “common purpose”, which ruled that he was equally liable for the deaths and injuries.

The doctrine of Common Purpose was a legal instrument instituted by the apartheid government which renedered accomplices liable for criminal or political offences by association. Thus, all parties committing a crime together were to face the same consequences, regardless of whether they carried out the same acts or knew of each other’s intent.

Mahlangu was found guilty and sentenced to death, but he appealed against his harsh sentence. The ANC launched a vigorous international campaign to mobilise governments to pressure South Africa to halt the execution of Mahlangu. Pleas for clemency by the United Nations, international organisations and influential figures fell on deaf ears. The Bloemfontein Appeal Court turned down Mahlangu’s appeal and he was executed on 6 April 1979. The trial inaugurated the increasing use of the “common purpose” clause in securing the death penalty against political and community activists in the 1980s.

Button aimed at mobilizing local and international support for stopping the execution of Solomon Mahlangu. Source: African Activist Archive

Button aimed at mobilizing local and international support for stopping the execution of Solomon Mahlangu. Source: African Activist Archive

"Several people were sentenced to death in the 1980s, and while some were acquitted, a number were executed. As stated above, in June 1983 Marcus Motaung, Jerry Mosololi and Simon Mogoerane (also known as the Moroka Three) – all members of MK – were executed. They were accused of engineering attacks on a police station in Orlando which resulted in the death of death of three policemen, the wounding of two and the destruction of police records. An international campaign to save the Moroka Three from execution was ignored by the apartheid government.

On 20 December 1985, South African security forces raided Lesotho, killing nine people. In retaliation, Andrew Zondo and several MK cadres placed a bomb at a shopping centre in Amanzimtoti which killed two children and injured 40 other people. Zondo was arrested and charged with five counts of murder. He was subsequently sentenced to death and refused leave to appeal, and was executed on 9 September 1986.

The last person to be hanged for a political offence was Jeffrey Boesman Mangena, who was executed on 29 September 1989. Mangena, a member of the ANC, was accused of murdering a school teacher who was a suspected of being an informer. On 28 September the UN General Assembly voted 148-0 – with two abstentions by the United States and Britain – to appeal to the South African government to commute his sentence.

The increase in executions from the late 1970s and through the 1980s was as a result of the intensified presence of MK inside the country. More guerrillas were infiltrated into South Africa and new cells established – evidenced by the number of attacks on government installations and an escalation in the number of casualties.

Death sentences commuted into prison sentences

Save the life of James Mange, a button by ANC, Zambia, 1979/1980. Source: African Activist Archive

Save the life of James Mange, a button by ANC, Zambia, 1979/1980. Source: African Activist Archive

Apart from the executions carried out in the 1980s, several people who were sentenced to death during this period had their sentences commuted to lengthy prison terms, due not to magnanimity but to international pressures focusing on the oppressive policies of the apartheid government.

In 1978 James Mange, together with 12 of his comrades, were arrested and charged with treason. On trial at the Pietermaritzburg Supreme Court, Mange was the only accused sentenced to death. The rest of the Pietermaritzburg Twelve, as they came to be known, received lengthy prison sentences. An international campaign was launched by the ANC to save Mange’s life. International bodies such as the United Nations, the Organisation of African Unity (now AU), the Non-Aligned Movement, and non-governmental organisations in South Africa all brought pressure to bear on the apartheid government. After spending 12 months on death row, on 11 September 1980 the Bloemfontein Appeal Court commuted Mange's death sentence to 20 years in prison. He was sent to Robben Island, where he served his sentence until his release as negotiations for a transition to democratic rule gathered pace.

In April 1980 nine members of MK appeared in court in the Silverton and Soekmakaar trial, accused of treason, terrorist activity, two counts of murder and robbery. All were charged under the “common purpose” clause to ensure that the prosecution obtained a conviction for each of them. The police targeted Johnson Lubisi, Petrus Mashigo, and Naphtali Manana for the death sentence as they were fingered by the prosecution as those behind the attack on Soekmekaar police station on 4 January 1980. On 27 November 1980, all three men were sentenced to death. Six of the other accused received lengthy sentence ranging between 10 to 20 years in prison. The ANC called on the international community to intervene, and on 2 June 1982 the state president commuted the sentences of the trio to life in prison.

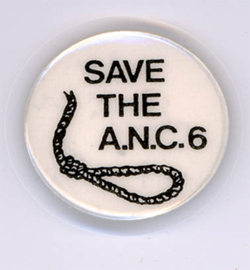

After an attack on the Booysens police station on 4 April 1980, three men were arrested: Anthony Tsotsobe, David Moise and Johannes Shabangu After their arrest they spent several months in indefinite detention. They were later taken to court where they were released but rearrested a few minutes later. The men were brought to court without legal representation and were asked to plead to charges of terrorism and treason. They were tortured and forced to sign confessions. The court rejected evidence that they had been tortured and found Tsotsobe, Moise and Shabangu guilty of high treason under the Terrorism Act. On 19 August 1981 they were sentenced to death by the Supreme Court. They lodged an appeal against their sentence, which was heard in September 1982, but the court ruled against them. Their sentences were noted by the UN, which called on the South African government to spare their lives. The ANC also launched a campaign to save its cadres from execution. The drive, known as the Save the ANC Six campaign, combined those convicted in two separate trials – that of Tsotsobe, Moise and Shabangu; and the case of Simon Mogoerane, Jerry Mosololi and Marcus Motaung. As stated above the last three men were all executed.

Save the ANC six. Source: African Activist Archive

Save the ANC six. Source: African Activist Archive

The final two cases in which death sentences were commuted to prison sentences are those of the Sharpeville Six and the Upington 14. In September 1984 protests broke out over rent increases in Sharpeville, but the protest evolved into an anti-government protest. The deputy mayor of Sharpeville, Jacob Kuzwayo Dhlamini, opened fire on the protestors, who turned on him and beat him to death. Seven men and one woman – Duma Khumalo, Oupa "Scotch" Diniso, Jaja Sefatsa, Theresa Ramashamola, Francis Mokhesi, Reid Mokoena, Christian Mokubung and Gideon Mokone – were arrested and charged with murder and public violence.

After their trial, which commenced on 23 September 1985, Mokubung and Mokone were found guilty of public violence, but not murder. The other six – the Sharpeville Six – were all sentenced to death. On 13 December 1985, they were granted leave to appeal, but the appeal was dismissed. Their lawyers applied for clemency to President PW Botha, who refused to intervene in their case. However, in May 1986 the accused were given leave to appeal their sentence. Local anti-apartheid organisations such as the Black Sash and South African Council of Churches; and international bodies such as the World Council of Churches and UN Special Committee Against Apartheid, all put pressure on the South African government to review the death sentences. After spending four years in prison, on 11 July 1988 – just fifteen hours before they were executed – they were granted an indefinite stay of execution. The fact that Theresa Ramashamola was one of the accused, and the first woman to be sentenced to death for a political offence, drew added attention to the trial. On 23 November 1988 PW Botha granted a reprieve to the Sharpeville Six. All were eventually released with the amnesty granted to all political prisoners in 1991.

Finally, on 13 November 1985, Lucas “Jetta” Sethwala, a police constable who fired on protestors, was murdered in Pabalello, a Black township in Upington. In April 1988, after a two-year trial, the 26 accused were convicted of the murder of Sethwala under the “common purpose” clause. In May 1989, 14 of those convicted, 13 men and one woman, were sentenced to death (hence the Upington 14). After sentencing the accused were immediately transported to Pretoria Central Prison and placed on death row. This became the largest number of people in South African history to be sentenced to death simultaneously. The rest of the accused were given prison sentences.

A banner of the City of London Anti-Apartheid Group calling for the release of the Upington political prisoners. Source: http://nonstopagainstapartheid.wordpress.com/

A banner of the City of London Anti-Apartheid Group calling for the release of the Upington political prisoners. Source: http://nonstopagainstapartheid.wordpress.com/

The case of the Upington 26 prompted international campaigns to reduce their sentences, one of these a campaign by the City of London Anti-Apartheid Group. During this period the government had begun secret negotiations with the ANC to dismantle apartheid. At the end of May 1991, the Bloemfontein Court of Appeal overturned the death penalty of the Upington 14 and ordered 11 of them to be immediately released.

Dealing with the past

When negotiations for a transition from apartheid to democracy got under way, the issue of the death penalty was tabled for discussion. The government and the ANC agreed to enact a moratorium on the death penalty in 1990. Later, in 1993, the National Party (NP) re-enacted the death penalty, but no one was executed. After the first democratic election in April 1994, a new constitutional dispensation was established and the death penalty was abolished on 6 June 1995. The gallows where people were executed were dismantled the following year. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission concluded that “all executions of persons convicted of political offences and/or which were politically motivated in the mandate period constituted gross violations of the rights of those so killed, for which the former government is held accountable”.

Those who had been executed were buried in pauper’s graves or on sites where protests were unlikely to erupt. In October 2010, the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) exhumed the bodies of six Poqo members who were hanged, and they were reburied at the Rebecca Street Cemetery in Pretoria. Among the deceased were Zibongile Serious Dodo, Nontasi Albert Sheweni, Jim Mountain Ngantweni, Donker Ntsabo, Veyisile Sharps Qoba and Mqokeleli Gladstone Nqulwana.

In November 2011 the Department of Correctional Services announced that the gallows at Pretoria Central Prison would be restored and converted into a museum. Subsequent to this announcement, on 15 December 2011, President Jacob Zuma officially opened the memorial museum and paid tribute to those who were executed for political offences.

To view a List of Political Prisoners executed in Pretoria Central Prison Click Here.