On 28 October 1917 more than 400 market gardeners from the Springfield Flats (Tintown) area in Durban, Natal (now Kwazulu-Natal) drowned when the banks of the Umgeni (uMngeni) River burst after heavy rains. The death toll would have been much higher if it were not for the bravery of six seine-netters who saved 176 people from drowning. The fishermen made five trips into the raging river in an oar-driven banana boat that they used for their everyday fishing.

The rescuers became known as the Padavatan Six; named after their captain, Mariemuthoo Padavatan. The rescue effort of the Padavatan Six is considered as one of the largest civilian acts of bravery in South Africa.

Tin Town

The Springfield Flats area, rich in alluvial soil, was made up of a large community of ‘free Indians’ (labourers released from their five years period of indenture on the sugar cane fields of Natal).

By 1917, the community was made of over 2,500 people who built wood and iron houses and turned the riverbanks into lush vegetable gardens. Their produce was hawked door to door around Durban. They experienced flooding many times over the years but this was the worst.

That fateful night, as the Tin Town farmers slept peacefully, the rains and the resulting debris dammed up the Railway and Connaught Bridges. When the pillars of the Railway Bridge cracked, a wall of water and debris came down on Tin Town. Many houses, people and livestock were immediately swept away.

The Volunteers

Mariemuthoo Padavatan, one of the leaders of a small community of seine-netters who lived and worked for generations on the beaches of Durban, was checking on his boats at Addington Beach for fear they may be smashed by the storm, when some of his workers arrived on a speeding fire-truck stating that the Borough Police Chief, one Inspector Alexander, needed boats, ropes and volunteers because Tin Town was flooding.

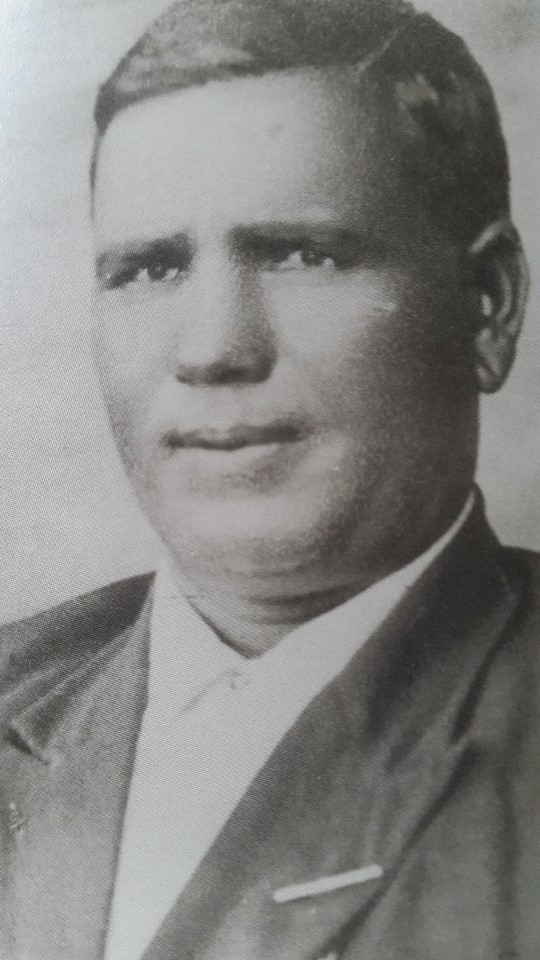

Born in 1887, Mariemuthoo Padavatan, 30 years old at the time, displayed leadership skills from a young age. He was already the chairman of the Natal Indian Fisherman's Association for ten years.

Padavatan quickly assembled a team of volunteers which included his older brother, Gangan Padavatan (1881-1945) who managed the financial and administrative functions of the Natal Indian Fishermen's Association while also running many successful enterprises such as building contracting, salesman, farmer, fisherman, fish wholesaler, et cetera.

Around 1912, Gangan Padavatan acquired a motor launch which was used as a commercial ferry and tour vessel around Durban Bay. The older Padavatan also assisted in the establishment of cemeteries in Clairwood and Queen Street and was a keen soccer player. He was married to Ponnama and they had seven children.

Sabapathy Periyasamy Govender, another volunteer, was born on 17 September 1890 in Madras (now Chennai), India. He arrived in Durban with his mother and younger brother in 1898. His mother worked as a cook for the Stainbank family. When he was twelve, his mother passed away and the two young brothers were adopted by a seine-netting family. He earned a great reputation for his boat building skills.

Mariemuthoo Padavatan also rounded up Rangasamy Naidoo, a fisherman and a sixteen year old, Kuppusamy Naidoo, who would later give up seine-netting for employment in the industrial sector.

Mariemuthoo Padavatan

Mariemuthoo Padavatan

The sixth volunteer was T. Veloo. Originally from India, he had settled in Kings Rest, close to the mangrove swamps which had an abundance of shrimp and was now a master shrimper. Out of the shrimping season, he netted with the Padavatans.

By the time the six volunteers arrived at Tin Town, the area was already submerged below the flood waters. Survivors were clinging onto the roofs of their houses, holding up jewellery as rewards, pleading to be saved. The Water Police, headed by Inspector Alexander, had abandoned their rescue attempt after their motorised boat nearly capsized in the raging waters.

The seine-net volunteer crew prepared to launch the banana boat which belonged to T. Veloo. They had carried Veloo’s boat, DNA 17, from Blue Lagoon to the Springfield Flats area. Out of fear for their safety, Inspector Alexander forbade the seine-netters from attempting a rescue.

The crew of six ignored Inspector Alexander and set off on their rescue mission.

The Rescue

Mariemuthoo Padavatan got hold of a trawling rope and directed the operations. One end of the rope was secured around a large tree trunk on high ground, and the other end was wound around his waist and secured to the prow of the boat leaving his hands free to control the rope.

He organised another group of seine-netters to control the rope tied around the tree. This land crew was made up of Seaman Doorasamy, Chinathumby Govender, and brothers Perumal and Rungasamy Pillay. These men were familiar with the techniques required of a shore crew in a seine-netting expedition. He instructed that the rope be fed to him slowly and steadily when they set out and pulled strongly when they would be rowing back. The men would have to coordinate their efforts according to the current, swell and wind.

They fell into familiar roles and tackled the rescue operation as if they were seine-netting the wild, slithering river. They knew what to do to keep the boat parallel to the current.

This was important because if the banana boat was broadside to the current it could turn turtle or, worse still, get engulfed in the huge swirls that came upon them from time to time.

Some victims in their fear and mortification made a fierce grab for the boat, rendering it unstable thus threatening to overturn it. They had to dodge sudden breakaway roofs and other flotsam hurtling towards them as well as having to contend with snakes wrapped around tree trunks, and frightened cats and dogs trying to get aboard. Bloated animal bodies and even dead people banged against their boat.

At any one time, four of the boatmen acted as oarsmen and two plucked people out of the river. They got the rescued people to lie flat on the bottom of the boat to keep the boat balanced. Pulling the boat laden with 30 to 40 flood victims was a physically trying and tiring task even for men of great physical strength.

The Victims

Dr Neelan Govender (son of Sabapathy Periyasamy Govender) recalls: “My father, Sabapathy, recounted the rescue mission with indescribable sadness. He remembered a family perched on a precarious rooftop. Even before they could reach this family, the young mother with her child clutched tight in her arms, slid off the roof with a heart-rending shriek. She and the child disappeared under the swirling waters and were swept away in the strong current.

“My father also recounted the story of a couple with a brood of hens, roosters and a bewildered goat on a rapidly sinking thatched roof,” Dr Govender said. “When they spotted the rescue operation, the man stood up praying and beseeching for help. The woman stretched out her hands, offering her precious mala (Hindu bridal necklace) as a reward for rescue but, before they reached them, the entire roof collapsed in the swirling torrent and the couple, poultry and goat sank beneath the surging waters. Their heads bobbed briefly and disappeared without a trace.”

One of the saddest stories to emerge was that of a man who lost fourteen members of his immediate family. His wife, children and other members of his family were all swept away by the waters, and he himself was almost buried in mud before he was rescued. He had one of his children on his shoulders that later died through exposure.” In another incident, a middle-aged woman, her husband and four children clambered onto the roof of their hut when the waters rose. They were overcrowded on the small roof and were in danger of slipping off so the woman managed to get onto the roof of another hut close by. No sooner had she reached her new perch than she realised that the gulf between her family and her had gotten wider due to the rapidly rising waters. She watched helplessly as their roof was swept down the river. She found their dead bodies the next day. Raman, a bedridden man, was unable to escape his room. His wife watched helplessly through a hole in the roof as the waters rose above his bed, drowning him. One of the happier stories was the rescue of a one-month-old baby, Rudhapersad Chotu Maharaj. He was snatched from the river by the Seine-netters before the swift current could drag him out to sea.

After five successful trips the rescuers were restrained from further rescue attempts by Chief Constable Donovan due to the falling light. “We were completely exhausted and were staggering like punch drunk men. They told us we had brought 176 persons to safety. I do not remember this, though. All I remember was a need for a brief rest,” T. Veloo later said.

Aftermath

The English press and the general public was generous in its praise of the “free Indians” and waxed lyrical of the Padavatan Six.

Chief Constable Donovan said, “I personally saw a part of what these men did, and I can only testify that they took a man’s part - a brave part, in rescuing people.”

Inspector Alexander said, “During my war campaigns I have seen and heard many noble deeds performed but I doubt whether they were nobler than those performed by these men on October 28th.”

It was reported that over 400 people lost their lives in the flood. Almost all the farmers lost their livelihoods.

Mr Oldham, an evaluator appointed by the Flood Relief Committee visited the area and during his inspection of the area, he discovered the body of a child hidden in the debris. How many other bodies were buried in so many layers of mud and debris one would never know?

The evaluator reported that the land was rendered useless for vegetable farming because large layers of white sand, carried by the rushing waters, were dumped on the once rich soil. Nonetheless, many resilient market gardeners later returned to their old location, despite the condition of the soil. They knew no other living and possessed no other skill.

Monies collected by the public in the name of the Padavatan Six, was graciously diverted by the heroes to a Relief Fund. They said they had given off their skills in the service of humanity with no thought of compensation.

On 8 December 1917 the City of Durban paid tribute to the Padavatan Six in a public ceremony. They were given gold medals and their Captain, Mariemuthoo Padavatan, was awarded a gold walking stick and a watch.

The M. Padavatan Primary School in Chatsworth was later named in memory of Mariemuthoo Padavatan, captain of the rescue mission.