Introduction

Lückhoff High School was established in 1935, as the first secondary school for the town’s ‘Coloured’ population of Stellenbosch. To date no publication exists that focuses solely on the history of the school. The original Lückhoff High school building, which is in the process of being memorialized, only houses two yearbooks. In contrast, there has been a great emphasis on the recording and preservation of the history of educational institutions that were established for the education of the White people of Stellenbosch. In an attempt to rectify this imbalance, this article focuses on the establishment and development of Lückhoff High School from 1939 until 1960, focusing on the school’s challenges and achievements as well as the way in which the school is being memorialized.

The Establishment and Development of Lückhoff School 1932-1969.

The need for Secondary Education

Secondary education for ‘Coloured’ people in South Africa started receiving attention in 1919. The primary objective thereof, was the training of more ‘Coloured’ teachers. Finding qualified ‘Coloured’ teachers in places like Stellenbosch, by way of example, was challenging. Consequently, qualified teachers had to be recruited from Cape Town. However, even these teachers often lacked the proper qualifications, so when necessary, White teachers assisted with teaching at certain Coloured schools[i]. Furthermore, Coloured people in Stellenbosch experienced difficulty accessing secondary education. Since the missionary schools only made provision for primary education, children who wanted to attend secondary schools needed to travel to Cape Town in order to attend schools there.[ii] At the time, Trafalgar High School, which was established in 1925, was a very popular choice.[iii] This lack of secondary education facilities for Coloured scholars eventually became so problematic that parents and missionaries appealed for the creation of a secondary school in Stellenbosch.

The Idea of a School

Missionaries in Stellenbosch were instrumental in the establishment of a secondary school. The idea of a secondary school for non-European children was first suggested to the Stellenbosch School Board on 21 September 1932. A representative of the missionaries, Reverend Weber from the Rhenish Missionary Society (RMS), noted that there was a great need for secondary education for Coloured children. The missionaries were evidently willing to do “everything in their power”[iv] to see the process through. Their efforts however, were stalled by the Education Department, who required the provision of a building for the school as one of the conditions under which the school could be established. This, however, was not affordable and the missionaries consequently approached the School Board for assistance. The School Board, in spite of being a mere extension of the Education Department, was perceived to have greater influence over such matters. This may have been because prominent academics like Dr Cillié from Stellenbosch University served on the board. Ultimately, a delegation that comprised of missionaries including Reverend Weber and Reverend A.F. Louw, as well as School Board members including Dr Cillié, approached the Superintendent-General of Education to discuss their reasons for not being able to comply with the stipulated conditions.[v]

The idea of establishing a secondary school was eventually supported by the Superintendent-General of Education, provided that the children who were in standard 5 and 6 at missionary schools were transferred to the new school; and that their parents would elect a school committee.[vi] However, at a meeting held in November of 1932 by the parents of learners in standard 4 and upwards it was decided that the election of a school committee should be left to the school board, as well as the matter of establishing a school, with the intention of opening the school in the first quarter of 1933.[vii]

The role of the School Board

Obtaining a building to house the new school continued to be a challenging process, resulting in a delay of its establishment and opening. Initially it was decided on a building in Rozenhof in Plein Street, but these plans were soon abandoned. The parents then suggested that a building belonging to a Mr. A.F. De Villers in Ryneveld Street, be acquired for this purpose.[viii] The process was somewhat hindered when the aforementioned building was inspected by an official from the Education Department, who declared the building unsuitable for its intended purpose. As a result, the municipality was approached by the School Board to purchase land and to ask the Education Department for funds to erect the new school building.[ix] Eventually, a aproposal to construct the school building on a site located in the vicinity of Stellenbosch Correctional Services, situated on the corner of Muller and Ryneveld Street, was approved by the Town Council. They estimated the building costs for the school to be £3000.[x]

In June 1933 the School Board applied to the municipality for a site that bordered Muller Street to the south, Hammanshand Way to the east, the current correctional services facilities to the west and an unnamed street, today Botha Street, to the north. The town council approved of the proposed use for this site.[xi] However, a new hurdle was encountered when these plans had to be abandoned because of complaints from two farmers, namely Mr H.N. Morkel and Mr A.H. Marnham, who asserted that the school grounds would block the roads leading to their farms.[xii] As a result, the school was temporarily housed in a two-storey building, which was rented from a Mr W. Lamberts in Andringa Street, while the School Board proceeded to apply to the municipality for land located next to the Mosque in Banhoek Road.[xiii]

The double story house of Mr Lamberts in Andringa Street, where the school was housed temporarily during the completion of the new school building from 1935 to 1938.

The double story house of Mr Lamberts in Andringa Street, where the school was housed temporarily during the completion of the new school building from 1935 to 1938.

Image source: Lückhoff Silver Jubileum, 1959 , p. 9.

Lückhoff School

With the inauguration of the school now months behind schedule, it initially appeared that the aforementioned site would become the final location.[xiv] The School Board also approved the suggested name of the school.[xv] It was decided to name the school after a missionary, Reverend Paul Daniel Lückhoff, who first arrived in Stellenbosch in 1830 and who did pioneering work with regards to the education of the Coloured people.[xvi] A letter was soon received from the Department of Education, in which it stated that the school could be expected to open on 1 January 1934. The school would cater for Standards 6 and 7, and provision was made for a principal as well as an assistant to the principal.[xvii]

The election of a principal posed the next challenge. The School Board nominated two White candidates to occupy the allocated positions: a Mr P.J. van der Westhuizen as principal and a Mr F. De Klerk as his assistant. However, the Superintendent-General of Education disapproved of these candidates on the grounds that there were suitable Coloured teachers who could fill these posts. On the other hand, one could argue that this was to maintain the racial separation of education within the education sector. The posts were consequently re-advertised. The School Board proposed the appointment of Mr P.J. van der Westhuizen as principal, Mr J. Theron as assistant teacher as well as a third teacher, in the person of Miss Joyce Williams. She would provide additional support, given the fact that the school was going to open with more than 60 learners in attendance.[xviii] In March 1934, the Education Department informed the School Board that Mr P.J. van der Westhuizen’s application was rejected, but that they approved the appointment of Mr Theron as an assistant to the principal. The School Board was adamant, however, that Mr Van der Westhuizen be appointed principal, given the fact that the school was to be opened on 1 April 1934.[xix]

Mr E. Moses, the first principal of the school (1935-1937)

Mr E. Moses, the first principal of the school (1935-1937)

Image source: Lückhoff Silver Jubileum, 1959 , p. 6.

Given the absence of a principal, the opening of the school was postponed until the 1st of January 1935 and the School Board was once again instructed to advertise the position of school principal.[xx] Several months later, the School Board nominated Mr E. Moses, a Coloured man, for the position of the principal. He was consequently appointed in October 1934, with Mr Jan Theron as his permanent assistant. It is interesting to note that although Mr Moses was qualified for the position, he was only appointed for one year beginning on 1 January 1935 and ending 31 December 1935, and also on a trial basis, while Mr Jan Theron was appointed as a permanent member of staff.[xxi] In a further twist, Mr Theron withdrew and Miss J.D.R. Gie, who started in the first term of 1935, replaced him.[xxii]

Opening of Lückhoff Secondary School: 1935-1939

Lückhoff Secondary School opened in January 1935. It was co-housed in a two-storey building belonging to Mr Lamberts in Andringa Street and in the house of Mr J. Alexander in Muller Street. There were 41 learners in Standard 6 and 23 learners in Standard 7.[xxiii] During this period, while the school was still being accommodated in a two-story house, there was an increase in the number of learners in attendance, necessitating the appointment of a third teacher, Mr D.S. Seane, from April 1935.[xxiv] The number of learners at the school continued increasing and by the end of 1935 this rose to 75 learners, [xxv] highlighting the significance the community attached to secondary education. The condition put forward by the Superintendent- General of Education that all learners in Standards 5 and 6 at missionary schools in Stellenbosch be transferred to the new school, suggests that these learners were from Stellenbosch.

The first group of learners in 1935. The staff are seated in the middle. From left: Miss D. Gie, Mr Moses and Mr D. Seane

The first group of learners in 1935. The staff are seated in the middle. From left: Miss D. Gie, Mr Moses and Mr D. Seane

Image source: Lückhoff Silver Jubileum, p. 20.

The school was also housed in the house of Mr J. Alexander in Muller Street at the time

The school was also housed in the house of Mr J. Alexander in Muller Street at the time

Image source: Lückhoff Silver Jubileum, 1959 , p. 9.

Since the land situated next to the Mosque, which was originally assigned for the building of the school, would not be able to accommodate all the learners, the search for suitable land for the school was not over.[xxvi] A final location for the construction of the school building was only secured in 1936 when the town council donated land for this purpose. The land was located on the corner of Banhoek Road and Ryneveld Street and this is where the original school building is still located today.[xxvii] Amidst the completion of the school building the number of learners grew, resulting in them being taught at three different locations in Stellenbosch, namely; the two-storey building in Andringa Street, a house in Muller Street and in a building that was called the “Race Stand” situated in Ryneveld Street.[xxviii]

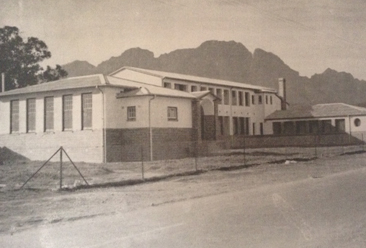

The school circa 1938-1939 in Banhoek Road, where the building still stands today

The school circa 1938-1939 in Banhoek Road, where the building still stands today

Image source: Lückhoff Silver Jubileum, 1959, p. 24.

Ever increasing enrolments at the school between 1935 and 1937 meant that not everyone could be accommodated. For this reason the Department of Education agreed to the municipality’s suggestion to rent the old Wesleyan Missionary School building, which was situated where the Town Hall is today, at a cost of £4 per month.[xxix] The saga continued when this building was so badly vandalized during the December school holidays of 1937 that the learners had to be moved to another location in Stellenbosch, complicating the job of the principal.[xxx] These complications could have been the motivation for the principal’s resignation, which brought his term to an official end on 31 December 1937. He was succeeded by Mr Alexander Stadion who commenced his three-month term as school principal for the period 1st of January to the 31 March 1938.[xxxi]

With the hope of officially opening the school on the 28th January 1939, the chairman of the School Board signed off the construction work done by the building contractor, Mr G. Blake.[xxxii] Though the school building was still not complete, it was finally deemed suitable enough for its purpose and was to be occupied on the 23rd of January 1939.[xxxiii] Due to a series of delayed deadlines, the school was only officially inaugurated on the 20th of May 1939.[xxxiv] During the opening of the school, a welcoming speech was made by Reverend A.F. Louw, himself a member of the Stellenbosch School Board. The architect, Mr Richie Fallon, handed the key of the school to the chairperson of the board, Dr G.G. Cillié, who ceremoniously unlocked the doors of the new school. Also present at this event was Professor Wilcocks, who delivered the main speech and thanked Mr P.J. Coetzee, who was the school principal at the time.[xxxv]

Learners at the inauguration of the new school, circa 1939

Learners at the inauguration of the new school, circa 1939

Image source: Lückhoff Silver Jubileum, 1959, p. 84.

CHALLENGES FACED BY THE SCHOOL

The challenges faced by the school related particularly to issues of accommodation and poverty.

Accommodation

It is maintained that Coloured schools faced problems of understaffing, overcrowding, unsuitable buildings, lack of library and hostel facilities, as well as unfavourable subsidies.[xxxvi] In February 1949 it became apparent that the school faced major accommodation issues. Mr. Coetzee, who was the principal of the school at the time, mentioned at a School Board meeting that the school was operating under difficult circumstances. Classes had to be offered in different parts of the building at different times, to accommodate learners in the limited space. As a result he wrote to the Department of Education, requesting that three additional rooms be added to the building to accommodate the learners.[xxxvii] The Education Department ignored the request initially, but eventually responded in November of 1949. Although they replied saying that they would do their best to try and improve the situation at the school,[xxxviii] only four additional classrooms were provided by the beginning of 1950.[xxxix]

Even though the school was granted additional accommodation, this was insufficient as the number of learners enrolling kept increasing. By 1960 an extra classroom was needed to accommodate the number of learners, which increased by 70 that year alone.[xl] The school was also in need of a suitably-equipped Science classroom. The need became so desperate that the school indicated they would be satisfied with a makeshift classroom until the proposed new classroom could be built.[xli] This suggestion was welcomed by the Department of Education and the makeshift classroom was erected in 1951.[xlii]

By 1953 the school had an extra woodwork classroom as well as a brand new science classroom.[xliii] The schoolyard eventually also became too small to accommodate the number of learners. Consequently, the principal made a number of attempts to get the Department of Education to approve the extension thereof.[xliv] However, because of the Group Areas Act of 1950, which was based on racial segregation, he encountered some difficulties, given the fact that an extension would have meant that the school would encroach on the White community.[xlv] His efforts paid off, however, and eventually his request was approved and the schoolyard was extended right up to Muller Street in 1956.[xlvi] The school was once again extended in 1958 when the School Board applied to the municipality for the purchase of the land northeast of the school, which was also approved.[xlvii]

The graphs that follow illustrate the annual increase in the number of learners at the school using the published statistics:[xlviii]

Poverty

A challenge faced by those who attended the school and alluded-to throughout the interviewing process was that of poverty. Reportedly, many people within the Coloured community were plagued by financial difficulties. Most of them worked at shops or for White families as gardeners and domestic servants, while others worked as hawkers. They were usually paid very little money and the selection of school subjects available to them, most of which focussed on practically-oriented subject material such as gardening, made it even more difficult for socio-economic advancement, thereby perpetuating the cycle of poverty they experienced.[xlix] Brian Poole, an ex-learner and subsequent deputy principal of the school, emphasized the issue of poverty, saying “poverty was a major challenge and that many people were unable to afford school uniforms for their children”.[l] However, it was also encouraging to learn that in spite of this, secondary schooling was prized and valued by members of the community and that people were determined to succeed, against the odds. According to Mr Hilton Biscombe, in an attempt to sustain its functioning and to assist those in need the school hosted regular bazaars to raise money.[li] Mr Abels, an ex-learner, has vivid memories of these occasions:

Die basaars van hierdie skool was ook van puik gehalte en dit was altyd klas pogings, wat natuurlik ook kompetisie tussen die klasse bewerkstellig het. Ons klas moes byvoorbeeld die meeste mandjies verkoop. Ek sien nog hoe die mammies van Die Vlakte by die hek inkom met die skinkborde vol koek of lekkernye.[lii]

Achievements

The first Standard 10 Class

One of the first major achievements of the school was celebrated at the end of 1950 when five of its Standard 9 (today known as Grade 11) learners passed and proceeded to Standard 10, making them the first group of learners to reach that level of education. The fact that all five of the learners got their senior certificates at the end of the following year represented a major milestone in the history of the school.[liii] The names of these learners were also published in the local newspaper, which bears testimony to the significance of this achievement not only to the school, but to the community as well. These learners were Asaph Josephs, Norman Pietersen, Stephen Sendin, Henry Cupido and Eva Johnson.[liv]

Accommodating learners outside of Stellenbosch

Nearly all the interviewees stressed the significance of Lückhoff High School’s willingness to accommodate learners from outside Stellenbosch and not just those who hailed from Die Vlakte or, later, Idas Valley. It is reported that people who attended the school came from the surrounding communities of Vlottenburg, Jamestown, Pniel and Kylemore and travelling in and out of Stellenbosch on a daily basis, in spite of the financial demands this imposed on them. Over a period of time learners reportedly started streaming in from Bredasdorp, De Aar, Malmesbury, Worcester and even South West Africa, today known as Namibia.[lv]

There was a strong underlying narrative highlighting the transformative role played by Lückhoff High School in making secondary school education accessible to people of Colour beyond Stellenbosch. When asked about the ways in which the community received those who were not from Stellenbosch, there was a general consensus that the learners were well received by, and well integrated into, the community reportedly because this boosted the number of learners enrolled at the school.[lvi] Integration was further aided by the fact that the learners from outside of Stellenbosch boarded with the families of learners from Stellenbosch.[lvii] It was also mentioned that the current mayor of Stellenbosch was also a learner from Tulbagh, just outside of Stellenbosch. This was used as a testimony to how well learners from outside of Stellenbosch were assimilated into the community.[lviii]

A number of explanations were offered in an attempt to explain both the school’s openness to accommodate learners from further afield, and why it was important at the time. Mr Brian Poole, who was a learner at the school from 1949 untill his matriculation in 1954, stressed that the school had a very good reputation among the Coloured population, especially with regard to the quality of the teachers who taught at the school.[lix] Although the school’s successes bear testimony to the fact that the teachers were skilled for the work they were doing, their specific qualifications were not always clearly evident in the School Board notes. Teachers were reportedly keen to obtain good qualifications. This was made possible by attending teacher training institutions, including Hewat Training College in Cape Town, as well as the Oudtshoorn Training College, which both opened during the 1930’s. As from 1953, teachers could pursue more specialized teacher training courses, including graduate teacher training courses such as those offered by the University of Cape Town.[lx] The findings of the Botha Commission, which was established to investigate the conditions of education for the Coloured population, attest to this.[lxi] Accordingly 58 percent of Coloured teachers employed at secondary schools had obtained a degree in 1953.[lxii]

Mr Jacques Cornelissen alluded to one of the teachers who worked at the school when he was a learner. The teacher was a Mr Parry who reportedly had an MSc degree in Mathematics from the University of Cape Town.[lxiii] Mr Hilton Biscombe took this narrative further by emphasizing the quality of the Afrikaans and English teachers at the school, including ex-teachers like Mr Hector who taught English.[lxiv] Furthermore, Mr Otto van Noie, who matriculated during the 1950’s, was of the opinion that the school’s prominence and popularity at the time stemmed from the quality of the education the school provided and the subsequent achievements of the school’s matriculants.[lxv]

The role of discipline

A common thread in all the narratives was the recollection of how disciplined the teachers and learners were. Mr Coetzee in particular is reputed for the skilful manner in which he created and maintained discipline and standards of excellence at the school. According to various accounts he was so devoted to excellence that he visited the primary schools in the area to ensure that learners who were to attend the school the following year knew in advance what was expected of them.[lxvi] It was also maintained that corporal punishment was the main way in which learners were disciplined at the school. Most of the interviewees attributed the discipline, which characterized the school, to corporal punishment. They jokingly reflected on this part of their time at the school, using phrases such as “the cane ruled supreme” and “ses van die bestes”, which refers to the number of times you would be caned if you were extremely naughty.[lxvii]

However, there were certain teachers who abused the practice of caning and who were brutal in the ways in which they administered punishment. Some remembered how humiliating it was to be disciplined at assembly in full view of their classmates and the teachers.[lxviii] Learners were also humiliated for arriving late at school by being made to walk around the school terrain during recess, wearing a placard hanged around their necks reading; ek is ‘n laatkomer (I am a latecomer).[lxix] A particularly disturbing disciplinary practice was ordering learners to stand in the school passage, bare feet, for the entire day, with no opportunity to use the toilet or eat.[lxx]

An ethos of excellence, resilience and pride

All the ex-learners remember the prize-giving as one of their highlights at the school. This was reportedly the occasion which acknowledged, affirmed and celebrated resilience and excellence. This also fostered an ethos of individual and communal pride. The Old Mutual as well as the Daniel Levenson trophies were floating trophies awarded annually in recognition of the top achievers, whilst those who excelled in sport received certificates of recognition for their achievements. This event contributed significantly to establishing the school’s ethos and its standing within the broader community.[lxxi]

The excellence, resilience and pride alluded to by all the interviewees is evident in their own school achievements and in what they achieved after completing secondary school. This is evident in the following accounts: Mr Howard Gordon, who is currently employed by Stellenbosch University and who works in the old Lückhoff School building, vividly remembers with great pride the award he received for cartography at this special ceremony;[lxxii] Mr Poole recalls with great pride having been the top matriculant in 1954, which inspired him to obtain the necessary qualifications and return to the school as a teacher[lxxiii] whilst Mr Willie Ortell received numerous trophies and certificates, and later became the first Coloured mayor of Stellenbosch.[lxxiv] It must, however, be mentioned that even though many learners at Lückhoff High School managed to achieve great success in life, there were also many who did not. The socio-economic circumstances of certain learners forced them to leave school in order to find work, earn money and assist with supporting their families.[lxxv]

Impacting the lives of the learners

There was consensus amongst all the interviewees of the positive impact the school has had in shaping their lives. There was also a sense of shared pride for the exceptional achievements of certain learners in higher education, medicine, commerce, law and sport. Evidence of this is proudly exhibited on the walls of the old Lückhoff school building.[lxxvi] Notable successful learners include Mr Brian Poole who became an Inspector of Education in the Western Cape; Willem Vergotini who became a medical doctor; Mr Basil Williams who became a prominent businessman; Conrad Sidego who became the ambassador for South Africa to Denmark and subsequently the current Mayor of Stellenbosch; Omar Henry who played cricket for Scotland and South Africa; as well as Ossie Woodman who became a successful soccer player at provincial level.[lxxvii] As controversial as certain of the school’s disciplinary measures may reportedly have been, one interviewee maintained that the discipline fostered in him while attending the school transformed his life. Yet another interviewee attributed the success he achieved to the guidance and inspiration he received from teachers like Mr Ronnie Britten who also conscientized him and others politically. This awareness is also believed to have contributed to identity formation and involvement in the broader struggle against apartheid.[lxxviii]

Sport

The school has a proud sporting legacy and various sports codes were practiced at the school. The winter sports codes included netball, soccer and rugby while the summer sport was tennis. The school also participated in an annual athletics event in Green Point, where they competed against other schools in the Cape Peninsula such as Gordon High School and Trafalgar High School in District Six. In 1966, the school came third overall in the meeting, out of a group of eight schools.[lxxix] By 1969 the school’s record had improved phenomenally and the soccer teams won trophies in all of their respective divisions while the cricket team won a trophy in the second division. This made soccer a very important part of the school’s sports ethos.[lxxx] It is maintained that the school was affiliated with the Western Province Senior School Union (WPSSU) and their learners could consequently compete against other schools belonging to this union.[lxxxi]

The school’s first rugby team in 1939

The school’s first rugby team in 1939

Image source: H. Biscombe, In ons bloed, p. 73.

Many of the former pupils of the school remember that the soccer team started to excel during the 1950’s with the arrival of the physical education teacher, Mr. Woodman, who instilled a love for soccer in the learners. He brought innovation to his training by showing the learners films of certain soccer matches and studying the formations and skills that would then be implemented in the soccer teams at the school. As a result of his intervention there was much improvement in the quality of the soccer played at the school and the success of the Under 15 and 17 soccer teams as well as players such as Davie Martin, is attributed to his involvement.[lxxxii] The school often participated successfully against other Coloured institutions such as Gordon High School as well as schools from Worcester and Tulbagh.[lxxxiii]

The cricket team played matches that were organized by the Stellenbosch Cricket Union at the time.[lxxxiv] An occasion that stood out with regards to cricket was a cricket tour to Port Elizabeth in 1962 for the Over-17s age group. The team also stopped to play against schools in Oudsthoorn and Mossel Bay. It is maintained that the team was responsible for funding the tour by hosting a dance as well as organizing boxing sessions in Idas Valley.[lxxxv] One of the interviewees recalled that because Lückhoff was the only secondary school that catered for the needs of the Coloured people in the area; whatever activities the learners participated in they aspired to excel at, particularly with regard to sporting achievements. This was especially the case at the annual athletics meeting held in Green Point, which most interviewees singled out as one of the highlights of their time spent at the school.[lxxxvi] Mr. Howard Gordon recalled this event:

I vividly remember our annual athletics meeting at, as we knew it, Green Point track in Cape Town. It was an extremely big affair. A special train would be hired for us for the day and, under the supervision of our teachers, the entire school would walk down to Stellenbosch station where we would board the train and make our way to Cape Town. After the proceedings of the day we would make our way back to Stellenbosch via the train. It was really a big affair and a special experience for all of us every year.[lxxxvii]

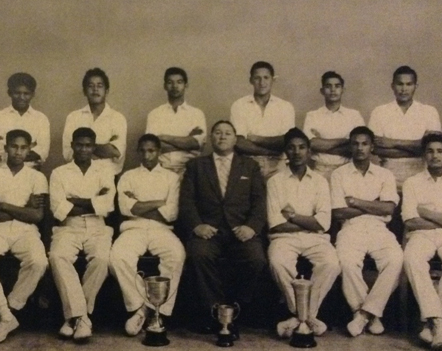

The first cricket team in 1958

The first cricket team in 1958

Image source: H. Biscombe, In ons bloed, p. 82.

25th Year Anniversary

In 1959 the school celebrated its 25th year anniversary.[lxxxviii] The celebratory programme was comprehensive and impressive. It commenced on Saturday the 3rd of October with a fete held at the school, and lasted for two weeks ending on the 16th of October. A banquet was held at the school on 7 October for the Stellenbosch School Board members.[lxxxix] Other events included an exhibition at the school where learners displayed their own creations made in their needlework, woodwork and art classes. Included in the programme was a wreath-laying ceremony at Reverend Lückhoff’s grave, after whom the school was named. On the evening of the wreath laying ceremony, a dinner was held at the school, honouring the ex-learners. Guests of honour, which included the Mayor, Mr Dempsey and the first principal of the school, Mr. Moses, were also in attendance.[xc] This year also marked Mr Coetzee’s twenty-first year of service to the school as principal.[xci]

The Staff in 1959. Seated in the front row second from the right, is Mr Parry. Mr Coetzee, the principal at the time, is seated in the middle; while the influential Mr. Britten is seated second from the right.

The Staff in 1959. Seated in the front row second from the right, is Mr Parry. Mr Coetzee, the principal at the time, is seated in the middle; while the influential Mr. Britten is seated second from the right.

Image source: Lückhoff Silver Jubileum, 1959, p. 30.

The Relocation and Memorialization of Lückhoff School

The relocation of Lückhoff High School

When the pioneers of apartheid, the National Party, rose to power in 1948, a number of racially discriminatory laws were passed.[xcii] These laws were designed to fit with and enact the governing regime’s spatial and social arrangement of a racially segregated society. The introduction of the Group Areas Act of 1950 was a very effective way of consolidating this.[xciii] Implementation of the Group Areas Act received significant attention in Stellenbosch the following year. Discussions regarding the provision of housing for the various racial groups who lived in Stellenbosch commenced in 1951.[xciv] In 1952 attempts were made to further expedite racial segregation in Stellenbosch by conducting a survey to determine who owned land, which areas were occupied by whom, and what the land was being used for.[xcv]

The forced physical removal of the Coloured community from certain areas in Stellenbosch dominated discussions at the local municipal meetings. Plans by the municipality to relocate the aforesaid people to the areas of Idas Valley and the vicinity of Du Toit Station were proposed.[xcvi] Regardless of certain objections, these plans were approved.[xcvii] There was a great sense of urgency among the White residents who reportedly pressurized the authorities to ensure that the relocation of the Coloured people took place swiftly. An article published in Die Eikestad in 1954 bears testimony to this. In the article, residents complained about a Coloured family who had not yet been removed and consequently still resided in Crozier Street among the White residents.[xcviii] The municipality heard their appeals and responded to the complaint as desired by the complainants. Segregation was further entrenched with land being made available in Idas Valley in 1954 for the establishment of a new primary school.[xcix] The Coloured people who resided in Die Vlakte, were directly and adversely affected by the new laws. Ten years later, after the successful forced removal of approximately 3700 “Coloured people” and their amenities, Die Vlakte was proclaimed a White residential area on the 25th of September 1964.[c]

The 1960’s saw the enforcement of particularly humiliating and dehumanizing racist laws that continue to have an effect on South African society today.[ci] Many learners at Lückhoff High School at the time were severely traumatized by the process of forced removal. This is exemplified by the recollection of the following memory, namely that of learners carrying their own benches to the new school building in Idas Valley while a truck carrying the rest of their belongings passed them along the way.[cii] It is also worth mentioning that at the time of the school’s relocation some learners were reportedly too young to comprehend the gravity of what was happening and consequently even felt excited about moving to a new school.[ciii] On the 30th of October 1969 Lückhoff High School was officially relocated.[civ]

The school in 1959

The school in 1959

Image source: H. Biscombe, In ons bloed, p. 85.

Memorialization

Memorialization may be defined as the social commemoration of people, experiences and events transmitted from the past to the present.[cv] This may be achieved in a number of ways, including museums, monuments, condolence notes, flowers, as well as pictures of those affected by a certain historical event or process.[cvi] Memorialization is important for a number of reasons. It enables a society to re-write biased narratives of the past, recognizes survivors of human rights violations in order to begin a process of healing and assists a previously divided society in need of reconciliation.[cvii]

Against a backdrop of the painful history of Lückhoff High School’s relocation, the effects of this on the lives of the people the school served, and on their relationships with members of other communities in Stellenbosch, numerous attempts have been made to memorialize the school. It is also worth noting that positive recollections of the school appear to take centre stage in the memorialization effort in a way that suggests its glorification. For example, during the interviews conducted for this study, none of the participants were particularly interested in discussing the negative aspects of being at the school. The participants were more focused on the ways in which the school positively impacted their lives. Even though the negative aspects of life in Stellenbosch as experienced by people whom the apartheid regime classified as Coloured were clearly illustrated, this was largely overshadowed by participants’ positive narrative regarding the school. When reading books such as In ons bloed[cviii], the impression may be created that surviving residents of Die Vlakte remember life in the community as one where racism was not a major concern. This was not the case: racism and classism was rife. Some scholars have argued that this phenomenon had become so firmly established, that many failed to challenge this and merely accepted it.[cix] Furthermore, there were also some tensions between Coloured people of the Christian faith and those who practised Islam. These tensions were particularly noticeable in sport. For example, when there were sports matches in the community, Christians and Muslims would play in different teams and against each other. These divisions in the community would have affected life at school too.[cx] These negative aspects were not recollected by the interviewees.

Given Stellenbosch University’s recent spate of negative publicity regarding transformation, it is important to note the institution’s role in memorializing Lückhoff High school as part of an attempt to address the painful legacy of the university’s role during the apartheid era.[cxi] It is particularly significant that the old Lückhoff building now houses what has become known as The Division for Social Impact.[cxii] Furthermore, it would appear that attempts were made by the community in the past to remember the school through their collaboration with the University of Stellenbosch. For example, in 2000, ex-learners were invited to celebrate the 65th anniversary of the school. This was a comprehensive celebratory programme, which commenced on 5 August and ended on 20 October that year. Activities included sports such as soccer and cricket, a thanksgiving service at the school hall and an old learner reunion. This was also an attempt at establishing reunion structures for those who attended the school.[cxiii]

It could also be argued that the memorialization of those affected by the forced removals actually started in 2006, when Stellenbosch University funded the publication of the well-received book, In ons bloed. The book provided an oral account of the lives of those who lived in Die Vlakte[cxiv] ,as well as the experiences of those who attended Lückhoff School. Furthermore, the university continued its efforts and contributions to the remembrance of those affected by the forced removals and dedicated the old Lückhoff School building to the community in 2007, as a symbol of transformation and reconciliation.[cxv]

At the beginning of 2008 a collaborative effort was made by members of the broader Stellenbosch community and the Division for Community Engagement (recently renamed the Division for Social Impact) of Stellenbosch University to memorialize the school. Financially supported by the Het Jan Marais Nasionale Fonds, the process entailed the permanent visual representation of the school’s history using photographs and other memorabilia obtained from ex-learners.[cxvi] The exhibition was launched in October 2008 and speakers at the event were the late ex-principal, Dr Fred Backman and the late Rector of Stellenbosch University, Professor Russel Botman.[cxvii] The celebration of the school’s birthday every year also serves as a way of continuing the memorialization process. During the annual celebrations ex-learners and teachers take the current students of the school on a guided tour and walk through the original school building. They also share the history with the learners. This was particularly illustrated this year, when the school celebrated its eightieth anniversary.[cxviii] At the celebratory event, Prof. Nico Koopman, Stellenbosch University's Acting Vice-Rector of Social Impact, Transformation and Personnel, said learners have inherited the Bill of Rights, ensuring that forced removals will not happen again and guaranteeing access to education. He added that learners also inherited the example of people who were involved in this school when things went horribly wrong, but accepted the challenge and responsibility and took it upon themselves to continue, despite difficult circumstances. He concluded by commenting on the inherited power of their spiritual traditions whether Christian, Muslim or secular.[cxix] This suggests that as the memorialization continues, the shared narratives provide a more balanced account of challenges and achievements.

Ex-learners at the launch of the exhibition at the school in 2008. From left to right – Mr Wilfred Daniëls, Mrs Yvette Pietersen, Mr Brian Poole and Mr Conrad Sidego, the current Mayor of Stellenbosch

Ex-learners at the launch of the exhibition at the school in 2008. From left to right – Mr Wilfred Daniëls, Mrs Yvette Pietersen, Mr Brian Poole and Mr Conrad Sidego, the current Mayor of Stellenbosch

Image source: Lückhoff’s pride honoured in photo exhibition(October 2015).

Conclusion

Stellenbosch is reputed for its schools and university. However, as highlighted in this study, the histories of its traditionally White educational institutions are recorded much more extensively than that of its traditionally Coloured educational institutions. This imbalance is evident in the sparsely recorded histories of Coloured educational institutions like Lückhoff High School. This study attempts to address the imbalance, providing an account of Lückhoff High School's history that highlights its challenges and achievements. To achieve this, the following sources were used; archival material, newspaper articles, interviews with ex-learners and pictorial sources. The findings of this study has provided evidence of Lückhoff High School’s significance to and its impact on, the lives of members of the Coloured community of Stellenbosch. It also aims to serve as a reminder that whilst the Coloured people of Stellenbosch may have accomplished much personally and socio-economically, Lückhoff High School’s contribution is not to be glorified at the expense of a community still fraught with challenges that were created by the historical injustices of South Africa’s past.

Endnotes

[i] E.M. Johnson: ’n Krities historiese waardeuring van die onstaan en opkoms van kleurling onderwys in die Stellenbosse dorpsgebied tot 1963, p. 162. MA Thesis, The University of the Western Cape, 1986. ↵

[ii] Ibid, p. 163. ↵

[iii] Superintendent-General of Education Report, 1925, p. 23. ↵

[iv] CAD/SBS/1/1/12 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 21 September 1932. ↵

[v] CAD/SBS/1/1/12 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 21 September 1932. ↵

[vi] CAD/SBS/1/1/12 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 21 October 1932. ↵

[vii] CAD/SBS/1/1/12 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 16 November 1932. ↵

[viii] CAD/SBS/1/1/12 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 15 February 1933. ↵

[ix] CAD/SBS/1/1/12 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 15 March 1933. ↵

[x] CAD/SBS/1/1/12 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 16 August 1933. ↵

[xi] CAD/SBS/1/1/12 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 21 June 1933. ↵

[xii] CAD/SBS/1/1/12 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 27 September 1933. ↵

[xiii] CAD/SBS/1/1/12 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 18 October 1933. ↵

[xiv] CAD/SBS/1/1/12 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 15 November 1933. ↵

[xv] CAD/SBS/1/1/12 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 20 December 1933. ↵

[xvi] F. Smuts (ed.): Stellenbosch: Drie Eeue, p. 313. ↵

[xvii] CAD/SBS/1/1/12 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 20 December 1933. ↵

[xviii] CAD/SBS/1/1/12 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 21 February 1934. ↵

[xix] CAD/SBS/1/1/12 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 21 March 1934. ↵

[xx] CAD/SBS/1/1/12 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 20 June 1934. ↵

[xxi] CAD/SBS/1/1/12 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 17 October 1934. ↵

[xxii] Lückhoff Silver Jubileum, 1959, p. 22. ↵

[xxiii] Ibid. ↵

[xxiv] CAD/SBS/1/1/12 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 17 April 1935. ↵

[xxv] E.M. Johnson: ‘n Krities historiese waardeering van die ontstaan en opkoms van kleurling onderwys in die Stellenbosse dorpsgebied tot 1963, p. 169. MA Thesis, The University of the Western Cape, 1986. ↵

[xxvi] CAD/SBS/1/1/12 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 20 March 1935. ↵

[xxvii] CAD/SBS/1/1/12 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 19 August 1936. ↵

[xxviii] Lückhoff Silver Jubileum, p. 22. ↵

[xxix] CAD/SBS/1/1/13 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 16 June 1937. ↵

[xxx] Lückhoff Silver Jubilem, p. 23. ↵

[xxxi] CAD/SBS/1/1/13 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 16 June 1937. ↵

[xxxii] CAD/SBS/1/1/13 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 18 May 1938. ↵

[xxxiii] CAD/SBS/1/1/13 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 15 February 1939. ↵

[xxxiv] CAD/SBS/1/1/13 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 17 May 1939. ↵

[xxxv] Lückhoff Silver Jubileum, 1959, p. 22. ↵

[xxxvi] F.G. Backman: The development of Coloured education with special reference to compulsory education, teacher training and school accommodation, p. 57. Doctoral Thesis, Stellenbosch University, 1991. ↵

[xxxvii] CAD/SBS/1/1/18 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 16 February 1949. ↵

[xxxviii] CAD/SBS/1/1/18 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 16 November 1949. ↵

[xxxix] CAD/SBS/1/1/20 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 15 March 1950. ↵

[xl] CAD/SBS/1/1/20Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 21 March 1951. ↵

[xli] CAD/SBS/1/1/20Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 20 June 1951. ↵

[xlii] CAD/SBS/1/1/20 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 15 August 1951. ↵

[xliii] Lückhoff Silver Jubileum, 1959, p. 25. ↵

[xliv] E.M., Johnson: ‘n Krities historiese waardeuring van die ontstaan en opkoms van kleurling onderwys in the Stellenbosse dorpsgebied tot 1963, p. 178. MA Thesis, The University of the Western Cape, 1986. ↵

[xlv] S. Dubow: Apartheid, 1948-1994, p. 37. ↵

[xlvi] CAD/SBS/1/1/20 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 19 March 1951. ↵

[xlvii] CAD/SBS/1/1/20 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 21 February 1951. ↵

[xlviii] E.M., Johnson: ‘n Krities historiese waardeuring van die ontstaan en opkoms van kleurling onderwys in the Stellenbosse dorpsgebied tot 1963, pp. 171-175. MA Thesis, The University oft he Western Cape, 1986. ↵

[xlix] G. Hendrich: Die dinamika van blank en bruin verhoudinge op Stellenbosch (1920-1945), pp. 25-26. Masters Thesis, Stellenbosch University, 2006. ↵

[l] B. Poole, 22 September 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[li] H. Biscombe, 8 September 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lii] H. Biscombe: In ons bloed, p. 74. ↵

[liii] CAD/SBS/1/1/20 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 12 May 1958. ↵

[liv] Staff Reporter, “Eerste 5 Matrieks in Lückhoff Skool slaag almal,” Die Eikestad, 2 February 1951, p. 2. ↵

[lv] W. Leith, 24 June and O. van Noie 23 September 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lvi] O. van Noie, 28 October, 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lvii] H. Biscombe, 28 October, 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lviii] J. Cornelisson, 28 October 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lix] B. Poole, 22 September 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lx] M. Horrell: The education of the coloured community in South Africa 1652-1970, pp. 45-46. ↵

[lxi] J.D. Holman: Coloured education in South Africa 1948-1976, p. 18. Honours Thesis. The University of Cape Town, 1984. ↵

[lxii] Botha Commission: Report of the coloured education commission, 1953-1956. ↵

[lxiii] J. Cornelisson, 30 September 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lxiv] H. Biscombe, 8 September 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lxv] O. van Noie, 23 September 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lxvi] H. Gordon, 24 July 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lxvii] W. Leith, 24 June 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lxviii] G. Hector, 28 August 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lxix] O. van Noie, 23 September 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lxx] J. Cornelisson, 30 September 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lxxi] E.M. Johnson: ‘n Krities historiese waardeuring van die ontstaan en opkoms van kleurling onderwys in the Stellenbosse dorpsgebied tot 1963, p. 190. MA Thesis, The University of the Western Cape, 1986. ↵

[lxxii] H. Gordon, 24 July 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lxxiii] B. Poole, 22 September 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lxxiv] W. Ortell, 22 September 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lxxv] J. Abels, 4 September 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lxxvi] J. Slamat, 9 June 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lxxvii] H. Biscombe: In ons bloed, p. 86. ↵

[lxxviii] H. Biscombe, 8 September 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lxxix] E.M. Johnson:‘n Krities historiese waardering van die ontstaan en opkoms van kleurling onderwys in the Stellenbosse dorpsgebied tot 1963, p. 190. MA Thesis, The University of the Western Cape, 1986. ↵

[lxxx] Ibid, p. 191. ↵

[lxxxi] W. Leith, 24 June 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lxxxii] O. van Noie, 23 September 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lxxxiii] J. Abels, 4 September 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lxxxiv] E.M. Johnson: ’n Krities historiese waardering van die opkoms en ontstaan van kleurling onderwys in die Stellenbosse dorpsgebied tot 1963, pp. 190-191. MA Thesis, The University of the Western Cape, 1986. ↵

[lxxxv] W. Leith 24 June 2015 and G. Hector, 28 August 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lxxxvi] H. Gordon, 24 July 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[lxxxvii] Ibid. ↵

[lxxxviii] E.M. Johnson: ‘n Krities historiese waardering van die ontstaan en opkoms van kleurling onderwys in the Stellenbosse dorpsgebied tot 1963, p. 180. MA Thesis, The University of the Western Cape, 1986. ↵

[lxxxix] CAD/SBS/1/1/20 Meeting of the Stellenbosch School Board Minutes, 20 May 1959. ↵

[xc] Staff Reporter, “Meer kleurling onderwysers nodig, se Adjunk-S.G.O., Hoërskool Lückhoff vier silver Jubileum,” Die Eikestad, 9 October 1959, p. 7. ↵

[xci] Lückhoff Silver Jubileum, 1959, p. 4. ↵

[xcii] A. Grundlingh: Removal from Die Vlakte, http://www.sun.ac.za/english/ (4 October 2015). ↵

[xciii] D. Smith: Apartheid in South Africa, p. 4. ↵

[xciv] Staff Reporter: “Group Areas Act and Stellenbosch: Council to obtain information,” Die Eikestad, 13 April 1951 p. 1. ↵

[xcv] Staff Reporter: “Survey for the Group Areas Act,” Die Eikestad, 8 February 1952, p. 1. ↵

[xcvi] Staff Reporter: “Raad finaal oor groepsgebiede,” Die Eikestad, 6 February 1953, p. 1. ↵

[xcvii] Staff Reporter: “Die Groepsgebiedewet weereens,” Die Eikestad, 6 February 1953, p. 4. ↵

[xcviii] Staff Reporter: “Kleurlinge nog tussen blankes,” Die Eikestad, 23 July 1954, p. 1. ↵

[xcix] Staff Reporter: “Nuwe Skool vir Idasvallei,” Die Eikestad, 19 November 1954, p. 19. ↵

[c] A. Grundlingh: Removal from Die Vlakte, http://www.sun.ac.za/english/ (4 October 2015). ↵

[ci] The genesis of the Armed Struggle, 1960-1966, http://www.sahistory.org.za (5 October 2015). ↵

[cii] H. Biscombe, 8 September 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[ciii] H. Gordon, 24 July 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[civ] O van Noie, 23 September 2015, Interviewed by A. Pietersen. ↵

[cv] Hoelscher, M. & Anheier, H.: Indicator suites for Heritage, Memory and Identity, in Heritage, Memory and Identity, Anheier, H. & Rajisar, Y. (eds.). p. 334. ↵

[cvi] J. Barsalou and V. Baxter: The Urge to remember: The Role of Memorials in Social Reconstruction and Transitional Justice, http://www.usip.org/ (5 October 2015). ↵

[cvii] Memory and Memorialization, www.csvr.org.za (5 October 2015). ↵

[cviii] See H. Biscombe, In Ons Bloed, 2006. ↵

[cix] C. Fransch: Stellenbosch and the Muslim Communities, 1896-1966, p. 154. MA Thesis, Stellenbosch University, 2009. ↵

[cx] Ibid, p. 162. ↵

[cxi] M. Mortlock: SASCO calls for speedy transformation at Stellenbosch University, http://ewn.co.za/2015/09/18/Sasco-calls-for-speedy-transformation-at-Stellenbosch-University (7 October 2015). ↵

[cxii] J. Slamat, 9 June 2015, C. Fransch: Stellenbosch and the Muslim Communities, 1896-1966, p. 154. MA Thesis, Stellenbosch University, 2009. ↵

[cxiii] Staff Reporter, “Kom deel in Lückhoff se feesvieringe,” Die Eikestad, 28 July 2000, p. 12. ↵

[cxiv] See H. Biscombe, In Ons Bloed, 2006. ↵

[cxv] Historical Background, http://www.sun.ac.za/english/about-us/historical-background (7 October 2015). ↵

[cxvi] Staff Reporter: “Laat ek jou van Lückhoff vertel,” Die Eikestad, 3 October 2008, p. 3. ↵

[cxvii] Staff Reporter, Lückhoff Onthou, Die Eikestad, 17 October 2008, p. 15. ↵

[cxviii] S. Lamprecht: SU helps Lückhoff celebrate its 80th anniversary, http://www.sun.ac.za/english/Lists/news/DispForm.aspx?ID=2951 (8 October 2015). ↵

[cxix] Ibid. ↵