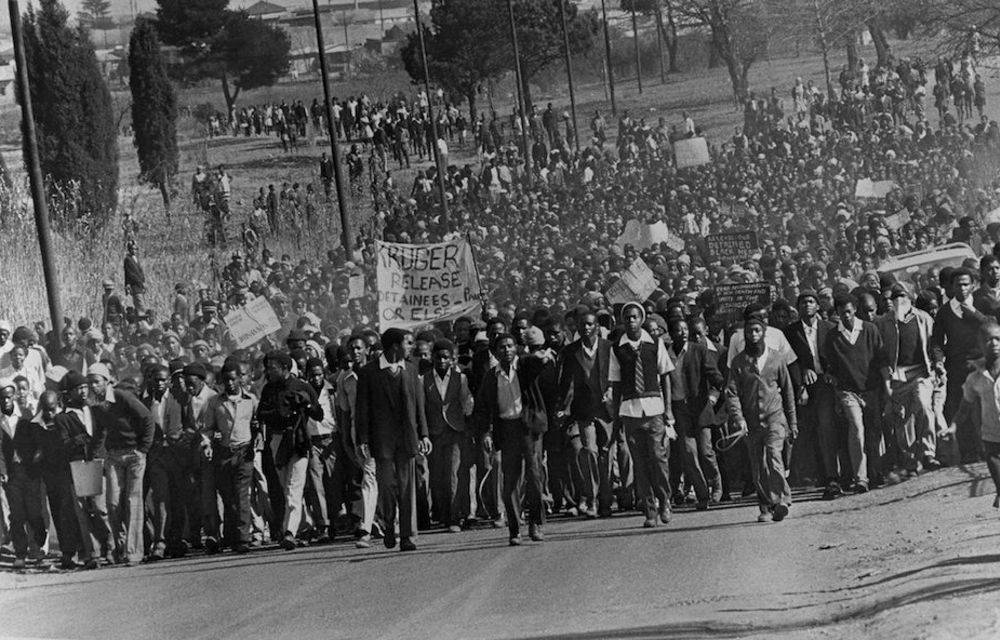

An image of bold, selfless youth in late 1970s South Africa inspired by the black radical consciousness philosophy. Image Source

Essay Question:

To what extent were Black South Africans were deprived of their political, economic, and social rights in the early 1900s and how did this reality pave the way for the rise of African Nationalism? Present an argument in support of your answer using relevant historical evidence.[1]

Background and historical overview:

There was no South Africa (as we know it today) before 1910. Britain had defeated Boer Republics in the South African War which date from (1899–1903). There were four separate colonies: Cape, Natal, Orange River, Transvaal colonies and each were ruled by Britain. They needed support of white settlers in colonies to retain power.[2] In 1908, about 33 white delegates met behind closed doors to negotiate independence for Union of South Africa. The views and opinions of 85% of country’s future citizens (black people) not even considered in these discussions. British wanted investments protected, labour supplies assured, and agreed on the fundamental question to give political/economic power to white settlers.[3] This essay pushes back in time to analyse how this violent context in South African history served as an ideological backdrop for the rise of African nationalism in the country and elsewhere in the world.

The Union Constitution of 1910 placed political power in hands of white citizens. However, a small number of educated black, coloured citizens allowed to elect few representatives to Union parliament.[4] More generally, it was only whites who were granted the right to vote. They imagined a ‘settler nation’ where was no room for blacks with rights. In this regard, white citizens called selves ‘Europeans’. Furthermore, all symbols of new nation, European language (mainly English and Dutch), religion, school history. In this view, African languages, histories, culture were portrayed as inferior. [5]

Therefore, racism was an integral feature in colonial societies, and this essentially meant that Africans were seen as members of inferior ‘tribes’ and thus should practise traditions in ‘native’ reserves. Whilst, on the other hand, in the settler (white) nation, black people were recognized only as workers in farms, mines, factories owned by whites. Thus, black people were denied of their political rights, cultural recognition, economic opportunities, because of these entrenched processes and politics of exclusion. In 1910 large numbers of black South African men were forced to become migrant workers on mines, factories, expanding commercial farms. In 1913, the infamous Natives Land Act, worsened the situation for black people as land allocated to black people by the Act was largely infertile and unsuitable for agriculture.[6]

Rise of African Nationalism:

In the 19th century, the Western-educated African, coloured, Indian middle class who grew up mainly in the Cape and Natal, mostly professional men (doctors, lawyers, teachers, newspaper editors) and were proud of their African, Muslim, Indian heritage embraced idea of progressive ‘colour-blind’ western civilisation that could benefit all people. This was a more worldly outlook or form of nationalism which recognized all non-white groupings across the colonial world as victims of colonial racism and violence.[7] However, another form of nationalism recognized the differences within the colonized groups and argued for a stricter and more specific definition of what it means to be African in a colonial world. These were some differences within the umbrella body of African nationalism and were firmly anchored during the course of the 20th century.

African Peoples’ Organization:

One of the African organisations that led to the rise of African nationalism was the African People’s Organisation (APO). At first the APO did not concern itself with rights of black South Africans. They committed themselves to the vision that all oppressed racial groups must work together to achieve anything. Therefore, a delegation was sent to London in 1909 to fight for rights for coloured (‘coloured’. In this context, ‘everyone who was a British subject in South Africa and who was not a European’).[8]

Natal Indian Congress:

Natal Indian Congress Natal Indian Congress (NIC) was an important influence in the development of non-racial African nationalism in South Africa. Arguably, it was one of the first organisations in South Africa to use word ‘congress’. It was formed in 1894 to mobilise the Indian opposition to racial discrimination in Colony. [9]The founder of this movement was MK Gandhi who later spearheaded a massive peaceful resistance (Satyagraha) to colonial rule. This protest forced Britain to grant independence to India, 1947. The NIC organised many protests and more generally campaigned for Indian rights. In 1908, hundreds of Indians gathered outside Johannesburg Mosque in protest against law that forced Indians to carry passes, passive resistance campaigns of Gandhi and NIC succeeded in Indians not having to carry passes. But, however, they failed to win full citizenship rights as the NIC did not join united national movement for rights of all citizens until 1930s, 1940s

South African Native National Congress (now known as African National Congress):

In response to Union in 1910, young African leaders (Pixley ka Isaka Seme, Richard Msimang, George Montsioa, Alfred Mangena) worked with established leaders of South African Native Convention to promote formation of a national organization. The larger aim was to form a national organisation that would unify various African groups.[10] On 8 January 1912, first African nationalist movement formed at a meeting in Bloemfontein. South African National Natives Congress (SANNC) were mainly attended by traditional chiefs, teachers, writers, intellectuals, businessmen. Most delegates had received missionary education. They strongly believed in 19th century values of ‘improvement’ and ‘progress’ of Africans into a global European ‘civilisation’ and culture. In 1924, the SANNC changed name to African National Congress (ANC), in order to assert an African identity within the movement.[11]

Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICU):

The Industrial and Commercial Workers Union African protest movements that helped foster growing African nationalism in early 1920s. Industrial and Commercial Workers Union (ICU) was formed in 1919 was led by Clements Kadalie, Malawian worker. This figure had led successful strike of dockworkers in Cape Town. Mostly active among farmers and migrant workers. But, only temporarily away from their farms and was very difficult to organise. The central question to pose is to examine the ways in which the World War II influence the rise of African nationalism? Essentially, there were various ways that WW II influenced the rise of African nationalism. [12]Firstly, through the Atlantic Charter, AB Xuma’s, African claims in relation to this Charter. In addition, the influence of politicized soldiers returning from War had a significant impact.

The Atlantic Charter and AB Xuma’s African claims Churchill and Roosevelt issued the Atlantic Charter in 1941, describing the world they would like to see after WWII. To the ANC and African nationalists generally, the Atlantic Charter amounted to promise for freedom in Africa once war was over. Britain recruited thousands of African soldiers to fight in its armies (nearly two million Africans recruited as soldiers, porters, scouts for Allies during war). This persuaded Africans to sign up and Britain called it ‘a war for freedom’. [13]The soldiers returning home expected Britain to honour their sacrifice, however, the recognition they expected did not arrive and thus became bitter, discontented, and only had fought to protect interests of colonial powers only to return to exploitation and indignities of colonial rule.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, this essay has attempted to examine the historical circumstances in which black people were denied of their political, economic, and social rights in the early 1990s. There are various that must be acknowledged in order to have a granular understanding of the larger and longer history of African nationalism, and this examination may exceed the scope of this essay. However, the central argument made here is that the rise of African nationalism in all its different ethos and manifestations was premised on humanizing black people in various parts of the colonial world. To stress this point, African nationalism emerged as a vehicle of resistance and humanization. Finally, African nationalism cannot be read outside the international context (as shown throughout the paper), as we have to take into account various factor which effectively influenced the spurge of this ideological outlook in society.

This content was originally produced for the SAHO classroom by

Ayabulela Ntwakumba & Thandile Xesi.

[1] National Senior Certificate.: “Grade 11 November 2019 History Paper 2 Exam,” National Senior Certificate, November 2019. Eastern Cape Province Education.

[2] Williams, Donovan. "African nationalism in South Africa: origins and problems." The Journal of African History 11, no. 3 (1970): 371-383.

[3] Feit, Edward. "Generational Conflict and African Nationalism in South Africa: The African National Congress, 1949-1959." The International Journal of African Historical Studies 5, no. 2 (1972): 181-202.

[4] Chipkin, Ivor. "The decline of African nationalism and the state of South Africa." Journal of Southern African Studies 42, no. 2 (2016): 215-227.

[5] Prinsloo, Mastin. "‘Behind the back of a declarative history’: Acts of erasure in Leon de Kock's Civilizing Barbarians: Missionary narrative and African response in nineteenth century South Africa." The English Academy Review 15, no. 1 (1998): 32-41.

[6] Gilmour, Rachael. "Missionaries, colonialism and language in nineteenth‐century South Africa." History Compass 5, no. 6 (2007): 1761-1777.

[7] Lester, Alan. Imperial networks: Creating identities in nineteenth-century South Africa and Britain. Routledge, 2005.

[8] Van der Ross, Richard E. "The founding of the African Peoples Organization in Cape Town in 1903 and the role of Dr. Abdurahman." (1975).

[9] Vahed, Goolam, and Ashwin Desai. "A case of ‘strategic ethnicity’? The Natal Indian Congress in the 1970s." African Historical Review 46, no. 1 (2014): 22-47.

[10] Suttner, Raymond. "The African National Congress centenary: a long and difficult journey." International Affairs 88, no. 4 (2012): 719-738.

[11] Houston, G. "Pixley ka Isaka Seme: African unity against racism." (2020).

[12] Xuma, A. B. "African National Congress invitation to emergency conference of all Africans."

[13] Kumalo, Simangaliso. "AB Xuma and the politics of racial accommodation versus equal citizenship and its implication for nation-building and power-sharing in South Africa."