Bookmarked by Dan Cameron in Art Forum as “what may turn out to be the most important exhibition of the 1990s”, the 2nd Johannesburg Biennale, which opened on 10 October 1997, was lauded internationally whilst contested at home, facing early closure and failing to be realised in subsequent years.[1] Titled Trades Routes: History and Geography, the biennale was curated by Nigerian-born, and at that stage New York based, curator Okwui Enwezor, as appointed by Christopher Till, executive director of the Johannesburg Biennale, and Bongi Dhlomo-Mautloa, director of the now defunct AICA: Africus Institute for Contemporary Art. Enwezor’s vision was to “look beyond the givens of history”, contesting the vogue of the terms ‘multiculturalism’, ‘postcolonial’ and ‘globalisation’ as reproducing neo-colonial relations, to explore “how economic imperatives of the last five hundred years have produced resilient cultural fusions and disjunctions”.[2] South Africa’s history as a point of commerce between East and West positioned the Biennale as a place to point out the converse effects of colonialism on the Global South and the New World, with much of the work by the artists from 63 nationalities grappling with the concepts of displacement, migration, exile, and trauma as pertains to identity and ideas of home. There was a sense of the forging of a new politics of place, as the fall of the Berlin wall, the collapse of Soviet Russia, the end of legislative Apartheid, and the demise of the British Empire through Hong Kong’s handover to China, pointed to a new figuration of the world at the end of modernity, which exceeded the “tendentious divisions” evident in polarities such as “inside/outside, native/alien, self/other”. [3] This prompted a curatorial primacy given to artists from Latin America, Eastern Europe, Asia and several countries aside from South Africa on the African continent.

Marc Latamie, Castor & Pollux, (1995), Installation Source: Trades Routes: History and Geography, the catalogue of the 2nd Johannesburg Biennale, edited by Matthew DeBord, Greater Johannesburg Metropolitan Council & Prince Claus Fund: Johannesburg and The Hague, 1997, page 138.

Marc Latamie, Castor & Pollux, (1995), Installation Source: Trades Routes: History and Geography, the catalogue of the 2nd Johannesburg Biennale, edited by Matthew DeBord, Greater Johannesburg Metropolitan Council & Prince Claus Fund: Johannesburg and The Hague, 1997, page 138.

‘Alternating Currents’ the main exhibition at the Electric Workshop, Newtown, curated by Enwezor and Octavio Zaya, introduced local audiences to the work of Coco Fusco, Tania Bruguera, David Hammons, Bodys Isek Kingelez and Isaac Julien, whilst in turn debuting South African work, such as Santu Mofokeng’s Black Photo Album/ Look at Me, 1890-1950 and Penny Siopis’ My Lovely Day to much wider audiences. Enwezor’s conception of nationality as “durational and contingent” led to a radical critique and abandonment of the standardised model of national pavilions that defined biennales up to that point in curatorial history.[4] Instead, in favour of new readings of citizenry against settlement, based on border crossings, immigration and diaspora, as well as the increased circulation of art itself, Enwezor enlisted Gerardo Mosquera (Cuba), Kellie Jones (United States of America), Hou Hanru (Hong Kong), Yu Yeon Kim (South Korea), and Colin Richards (the sole South African) to curate exhibitions in Johannesburg and Cape Town. These exhibitions, notably ‘Transversions’ by Kim at Museum Africa, and ‘Graft’ by Richards at the IZIKO South African National Gallery in Cape Town, dealt with building new “contact zones” for art and artists through principles of mutation and translation.[5]

However, Enwezor’s nationless prerogative was at odds with a new democracy still in formation. The international scope of the Biennale, and the reformation and reinvigoration of the form of the biennale itself, looked outwards, beyond the immediate concerns of many South Africans, to a networked audience well versed in critical discourse and well-travelled. Despite several components of Trade Routes taking place outside institutional spaces, and made public on billboards, at bus stops, and on the internet, local audiences and media felt disconnected from the Biennale – both in its privileging of the international, eliding direct engagement with South African history, and as alienating in form due to the prominence of ‘new media’ like video and installation still novel within post-Apartheid visuality, and thus misread as culturally imperialist. This perception was paired with a xenophobic scepticism directed at Enwezor, as “captive of the white intelligentsia” and a “pretend-African”, which spoke of a parochialism and territorialism emblematic of the isolation years of Apartheid, marked by an inability to find solidarity beyond nationalism, a sensibility which extended into the cultural interregnum of the first post-Apartheid years.[6] However, this resistance towards the Biennale was premised on an actual missed opportunity to centralise debates specific to South Africa at that moment – whilst the Biennale opened in Johannesburg, Pik Botha was submitting his amnesty application at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission housed in the Sanlam Centre close to biennale venues. The failings of the curatorial team of the Biennale was thus to structure the exhibition along a thematic framework understood firstly as relevant, and legible, to the South African context, beyond the inclusion of South African work that grappled with the local such as William Kentridge’s Ubu Tells the Truth (1997) in ‘Transversions’. This approach extended to the biennale conference organised by Olu Oguibe, where topics such as ‘Home and Exile’, ‘Cultures in Diaspora’, ‘The Politics of Mega-Exhibitions’, ‘Cinema and Globalization’, and ‘Culture and Rupture in the Digital Age’ skirted around debates occurring in the South African art scene, including what Jean Fisher deemed the “recognition of the voice of the ‘Other’, but a continuing control of the conditions of its reception”[7] and Clive Kellner’s declaration that “there is a sense that South Africa needs to be decolonised”[8]

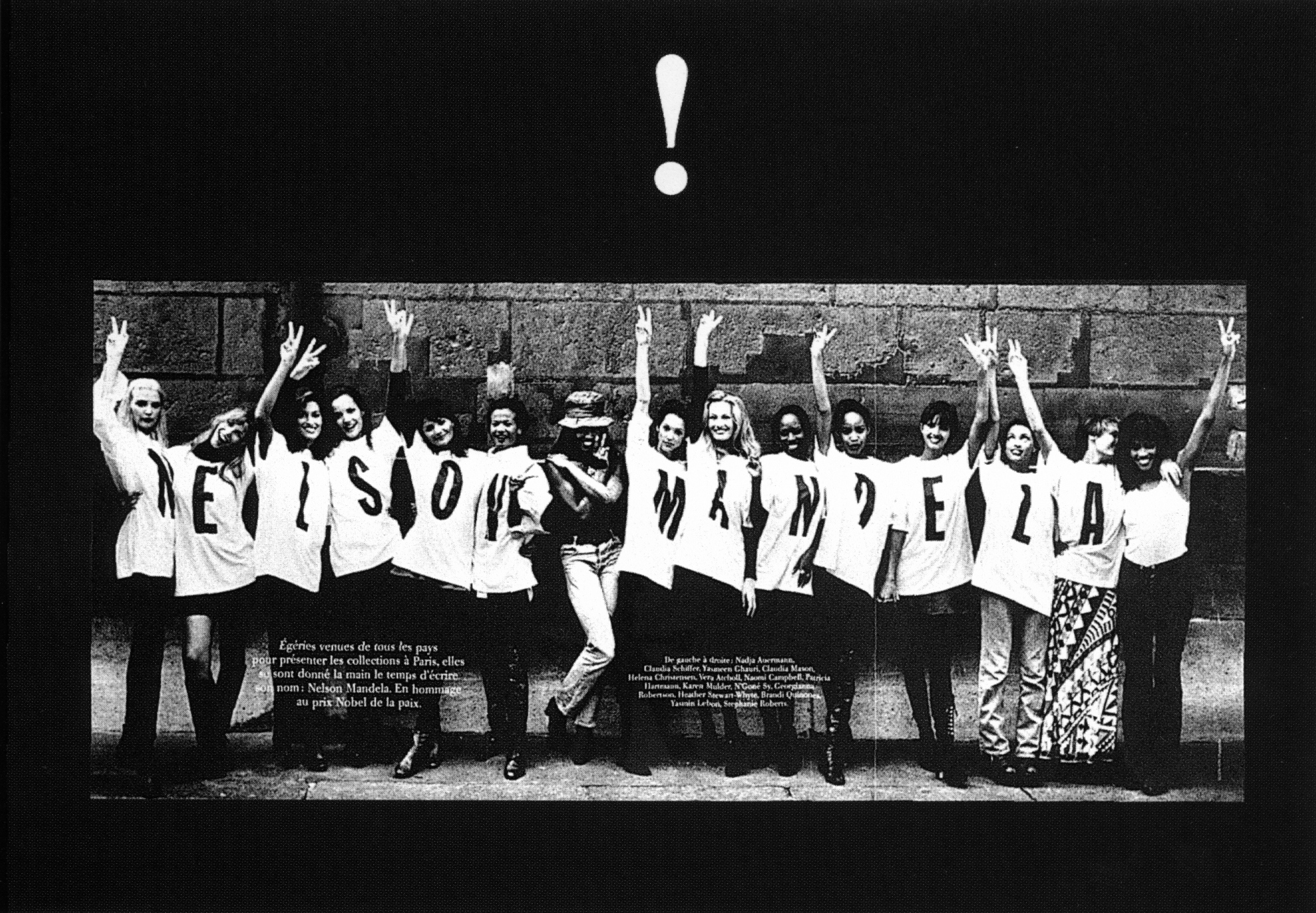

Renee Green, Vogue par Nelson Mandela (Taste Venue), (1994), Black and White Photograph Source: Trades Routes: History and Geography, the catalogue of the 2nd Johannesburg Biennale, edited by Matthew DeBord, Greater Johannesburg Metropolitan Council & Prince Claus Fund: Johannesburg and The Hague, 1997, page 106.

Renee Green, Vogue par Nelson Mandela (Taste Venue), (1994), Black and White Photograph Source: Trades Routes: History and Geography, the catalogue of the 2nd Johannesburg Biennale, edited by Matthew DeBord, Greater Johannesburg Metropolitan Council & Prince Claus Fund: Johannesburg and The Hague, 1997, page 106.

These misalignments and frictions led to a closing of doors at the very moment South African art gained widespread traction through the confluence of curators and artists the Biennale drew, with the Greater Johannesburg Metropolitan Council, the primary funder, not renewing its support. Although Trade Routes revolutionised the biennale, and led to unprecedented exposure and professionalisation for local artists and galleries, it also signalled the final iteration of the biennale, per definition a serial form, failing to implement a structure that would sustain itself in Johannesburg. Enwezor laments this closure, calling it “a profound disappointment”, and indicative of “the rancid politics of the country, where the scope of the imagination was not very broad”.[9] Yet the predominant local reception in 1997 does attest to the failings of the directors and curators of the biennale to mediate its significance, and cultivate an understanding and appreciation beyond privileged sectors. As Carol Becker asked, was it “possible to create a transnational biennale in a country not yet a nation?”[10]

Endnotes

[1] Dan Cameron, ‘Global Warming’, Art Forum December 1997, reprinted in Trade Routes Revisited, Stevenson: Johannesburg and Cape Town, 2012, page 66. ↵

[2] Okwui Enwezor, ‘Introduction – Travel Notes: Living, Working, and Travelling in a Restless World’, Trades Routes: History and Geography, the catalogue of the 2nd Johannesburg Biennale, edited by Matthew DeBord, Greater Johannesburg Metropolitan Council & Prince Claus Fund: Johannesburg and The Hague, 1997, page 7 & 9. ↵

[3] ibid: 9 ↵

[4] ibid: 10 ↵

[5] ibid: 12 ↵

[6] Okwui Enwezor, ‘Reflections’, in Trade Routes Revisited, Stevenson: Johannesburg and Cape Town, 2012, page 17. ↵

[7] Jean Fisher, ‘The Work Between Us’, Trades Routes: History and Geography, the catalogue of the 2nd Johannesburg Biennale, edited by Matthew DeBord, Greater Johannesburg Metropolitan Council & Prince Claus Fund: Johannesburg and The Hague, 1997, page 21. ↵

[8] Clive Kellner, ‘Cultural Production in Post-Apartheid South Africa’, Trades Routes: History and Geography, the catalogue of the 2nd Johannesburg Biennale, edited by Matthew DeBord, Greater Johannesburg Metropolitan Council & Prince Claus Fund: Johannesburg and The Hague, 1997, page 31. ↵

[9] Okwui Enwezor, ‘Reflections’, in Trade Routes Revisited, Stevenson: Johannesburg and Cape Town, 2012, page 11. ↵

[10] Carol Becker, ‘The Second Johannesburg Biennale’, in Art Journal, Summer 1998, republished in Trade Routes Revisited, Stevenson: Johannesburg and Cape Town, 2012, page 81. ↵