The 1967 Terrorism Act was one the most important pieces of legislation passed by the South African apartheid regime. Though the Act’s stated purpose was to facilitate the government’s fight against ‘terrorists,’ police used the law to pursue and prosecute various organizations and individuals who resisted state control. Enforcement of the Act allowed for almost unchecked control by security forces over detainees, and many of those detained under the Terrorism Act reported abuse by police forces. Others died in detention. As law professor John Dugard wrote in 1978: ‘Although designed to combat terrorism, the Terrorism Act has itself become an instrument of terror.’(Dugard, 1978: 136)

Legal Precedents

While the Terrorism Act was, to 1967, the most comprehensive, all-encompassing, and police-empowering piece of apartheid legislation, the Act was not entirely without precedent. The security laws of the 1950s and 1960s served as clear models for the Terrorism Act.

Suppression of Communism Act, No 44 of 1950

In 1950, the National Party passed the Suppression of Communism Act, No. 44 of 1950. This law not only illegalized the South African Community Party (SACP) but also endowed the Governor-General with the right to declare a political party unlawful at any time if they were found to be pursuing ‘communistic’ goals. (Horrell, 1978, 414) ‘Communist’ aims were purposefully vaguely defined, and non-communists were frequently arrested under the jurisdiction of the Act. (Dugard, 1978, 155) In 1976, with the cooling-off of Cold War tensions between the Soviet Union and United States, the Suppression of Communism Act was renamed the Internal Security Act. Correspondingly, the Act was extended to include not only communists but all those seeking to ‘endanger the security of the State or the maintenance of public order’ (Dugard, 1978, 155).

Criminal Procedure Act and Other Security Laws

The Criminal Law Amendment Act, No. 8 of 1953 bears many similarities to the Terrorism Act though it pertains to protests and protestors rather than terroristic activities and terrorists. This Act prescribed the punishment for those protesting the government or any of its laws, for inciting or encouraging another person to protest, or for receiving or soliciting any assistance in organizing a protest. (Horrell, 1978, 431) The Criminal Procedure and Evidence Amendment Act, No. 29 of 1955 as well as the Criminal Procedure Act, No. 56 of 1955 further increased the power of the government over dissidents. These Acts endowed judges and police with increased measures of autonomy and independence with regard to warrants and arrests. (Horrell, 1978: 434)

In the 1960s, the National Party began passing laws which set and increased the duration of legal detention without the possibility of bail or the necessity of charges brought against the prisoner. The first act of this nature was the General Law Amendment Act, No. 39 of 1961. An amendment to the Criminal Procedure Act, this law allowed for 12 day detention without opportunity of bail or the right to habeas corpus. (Horrell, 1978: 468) The General Law Amendment Act, No. 37 of 1963 further amended the Criminal Procedure Act and provided many the same stipulations for imprisonment as the Terrorism Act later would. The 1963 law allowed for arrests without warrants and detention for anyone suspected of ‘sabotage’ or of violating the Suppression of Communism Act or the similarly motivated Unlawful Organizations Act, No. 34 of 1960. A prisoner would not have the right to visitors and could be held for up to 90 days unless the Commissioner of Police allowed for their release. The 90 day term of imprisonment was renewable, however, and detainees could be rearrested repeatedly following their release. (Horrell, 1978: 469) The Criminal Procedure Amendment Act, No. 96 of 1965 lengthened the span of detention to 180 days, still renewable (Horrell, 1978: 471).

First Pieces of Anti-Terrorism Legislation

One of the clearest precedents to the 1967 Terrorism Act was South Africa’s first legislative response to terrorism, the General Law Amendment Act, No. 76 of 1962, also known as the known as the ‘Sabotage Act.’ This Act stated that anyone who willfully ‘injured, obstructed, tampered with or destroyed the health or safety of the republic ”¦ could be tried for sabotage.’ According to the law, this specifically meant anyone who interfered with ‘water, light, power, fuel, or foodstuffs, sanitary, medical, or fire emergency services.’ (SADET, 2004: 345)

Similarly, the General Law Amendment Act, No. 62 of 1966 amended the Suppression of Communism Act to allow for detention of terrorists for 14 days without the requirement of a warrant. Anyone could be arrested under this act by a policeman above the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel if the policeman had any grounds to suspect someone was a terrorist. Though detainees could not be held longer than 14 days, the Commissioner of Police could request a judge to extend the detention sentence. Between the law’s enactment and 6 February, 1968, 91 people were detained under this act, 38 of whom served sentences longer than 14 days, according to a report by the Minister of Police (Horrell, 1978: 472-473)

Terrorism Act of 1967

The first aim of the Terrorism Act was to define ‘terrorism’ or ‘terroristic activities.’ Section Two clarifies, in relatively vague wording, the deeds included under these umbrella terms. The Act defined someone as participating in terroristic activities if they acted ‘with intent to endanger the maintenance of law and order’ or if took take action which ‘incites ”¦ commands ”¦ aids ”¦ encourages’ another person to commit such an act (2.1.a).

The Terrorism Act further banned undergoing training, encouraging another to undergo training (2.1.b), or possessing any weapons (2.1.c) with the intention of conducting or learning how to conduct any of twelve explicit deeds. Among the activities specifically listed: preventing anyone from maintaining ‘law and order’ (2.2.a), promoting, ‘any object’ by ‘intimidation’ (2.2.b), causing ‘general dislocation, disturbance or disorder’ (2.2.c), or damaging production of food or ‘commodities’ (2.2.d). The Act also referred to crimes with potential political motivations or effects: causing or encouraging resistance to the government (2.2.e), furthering ‘any political aim’ including ‘any social or economic change’ by violence or with the co-operation or direction of any foreign government or institution (2.2.f), or encouraging ‘feelings of hostility between the White and other inhabitants’ of South Africa. (2.2.i) Similarly, the Act banned actions which could disrupt everyday life in the Republic: causing ‘serious bodily injury’ or endangering another’s’ safety (2.2.g), causing ‘substantial financial loss to any person or the state’ (2.2.h), disturbing any supply of light, power, food, fuel, water or medical, fire, postal, telephone, or radio services (2.2.j), obstructing the free movement of any traffic on land, at sea or in the air (2.2.k), or, finally, embarrassing, in any way, ‘the administration of the affair of the State.’ (2.2.l) Someone accused of committing one of these deeds would be presumed guilty until proven innocent (2.2). Anyone found guilty of participation in ‘terroristic activities’ faced a minimum sentence of five years in prison with the possible imposition of the death penalty. (2.1)

The Terrorism Act specified what could be used as evidence in discovering and prosecuting terrorists. The Act allowed documents to serve as evidence if they were acquired from people, places, or archives associated with an organization which the accused supported or joined. ‘Any document’ found in the possession of the accused or any member of any organization which the accused supported could be used against the accused in court (2.3.a). Records ‘found in or removed from’ any premises utilized by any organization supported by the accused were also admissible evidence. (2.3.b) Finally, the court could utilize any files kept ‘by or on behalf of an organization’ which the accused supported or of ‘any person having a name corresponding substantially to that of the accused’. (2.3.c)

Section Three extended the purview of the Act beyond merely the terrorists themselves. Any person found guilty of hiding or ‘indirectly’ assisting anyone they might believe to be a terrorist could be found guilty and receive the same punishment as someone accused of treason. Conviction meant a minimum of five years in prison or possibly even the death penalty. (3)

Sections Four and Five clarify who retained the jurisdiction over crimes committed in violation of the Terrorism Act and the procedure and structure of the trial of someone accused of being a terrorist. Regardless of where a violation of the Act was committed ‘any superior court or attorney general’ in South Africa had jurisdiction over this offence as ‘if it had been committed within’ their area of authority. (4.1) The Minister of Justice, too, could determine where any trial for a violation of the Act would take place. (4.2) The Act lists specific procedures for the trial of those arrested under the Act, including the explanation that the accused would be tried by a judge without a jury (5.a) and that joint trials were permitted for offences committed by ‘two or more persons’. (5.c)

The most infamous features of the Terrorism Act came in the notorious Section Six which deals with the detention of alleged terrorists. According to this section, if any police officer of or above the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel believed that any person was a terrorist or was withholding information on terrorists, that person could be arrested ‘without warrant and [be] detain[ed]’. The circumstances of their detention remained ‘subject to such condition as the Commissioner [of the South African Police] may determine’ and the accused could be held ‘until the Commissioner orders [their] release when satisfied’ that they have provided all useful pieces of information (6.1). ‘As soon as possible’ following the arrest of an alleged terrorist, the Police Commissioner was required to supply the Minister of Justice with the detainee’s name and place of imprisonment. Once a month, the Commissioner was required to supply the Minister with the reasons why the prisoner should not be released. (6.2)

Prisoners arrested under the Terrorism Act were essentially at the mercy of the Minister of Justice. The Minister retained the power to order the release of any detainee ‘at any time.’ (6.4) No ‘court of law’ could order the release of someone arrested under the Act. (6.5) Correspondingly, detainees retained the right to write to the Minister ‘at any time’ with regard to their ‘detention or release’. (6.3) However, other than the Minister or an ‘officer in the service of the State acting in the performance of [their] official duties,’ no one could visit an individual detained under the Terrorism Act. Furthermore, ‘no person’ was ‘entitled’ to official information about the prisoner. (6.6) ‘If circumstances so permit,’ the final clause of Section Six reads, ‘a detainee shall be visited in private by a magistrate at least once a fortnight.’ (6.7)

The final sections of the Terrorism Act indicated the tension the Act created between the judiciary and security forces in South Africa. An earlier portion of the law had ensured that all trials brought under the Act would function under the laws ‘relating to procedure and evidence.’ (4.3) Section Seven further ensured that the judiciary would maintain some control over the trials of those arrested under the Act. All warrants, summons, and subpoena, even those on detainees arrested under the Terrorism Act, remained ‘of force and effect’. (7.1) Warrants remained binding and those arrested under ‘any’ warrant were, ‘as soon as possible,’ to ‘be taken to the place mentioned in such warrant’. (7.2) These measures ensured that, legally, the security forces did not retain complete control, unaccountable to the judiciary, over their prisoners.

Yet, Section Eight reinforced the power of the Attorney General with regard to terrorists: ‘no trial for an offence under [the Terrorism Act could] be instituted without [their] written authority’ (8). The Act was assented to on 12 June, 1967.

The Terrorism Act departed from the stipulations of preceding security laws in a number of important ways. The 90 and 180-day detention laws, for example, allowed for public access to information regarding detainees; the Terrorism Act included no such provision (Dugard, 1978: 118). Furthermore, the Terrorism Act was the first piece of security legislation to allow for unlimited detention of suspected criminals. This fact remained especially significant due to the vague language of the crimes listed in Section Two. The Terrorism Act could be used to arrest someone for almost any crime and the burden of proof lay not in the arresting officer to prove the detainee’s guilt, but in the ‘terrorist’ themselves to prove their innocence. ‘In theory,’ Denis Herbstein wrote in 1978, because of the Terrorism Act’s ban on purposefully obstructing travel (2.2.k), someone ‘who was pushing [their] broken down car along the highway could be hanged if [they] could not show that [they] had simply run out of petrol.’ (Herbstein, 1978: 36)

Yet, the Terrorism Act also bears many similar features to its legal precedents. Like the 180 and 14-day detention laws, the Terrorism Act did not give those held under its purview the right to see a legal advisor (Dugard, 1978: 255-6). The Terrorism Act, too, bears many similarities to the Sabotage Act, but goes further in defining and banning acts deemed potentially harmful to the republic. Like the Sabotage Act, the Terrorism Act did not protect the accused from ‘double jeopardy;’ someone accused under the Terrorism Act could be tried for the same crime multiple times under multiple pieces of security legislation, as was often the case when defendants faced similar charges under the Suppression of Communism Act and the Terrorism Act (Dugard, 1978: 260-1). Building off the Suppression of Communism Act and the Unlawful Organizations Act, the Terrorism Act applied to both individuals and any organization with which they were involved. In fact, the crime of colluding with a ‘foreign government or institution’ (2.2.f) may serve as a not-so-subtle reference to the Soviet Union and the CPSA.

Passage of the Act

During much of 1967, the South African government made repeated statements regarding ‘terrorist attacks on South Africa’s borders’ which created almost immediate white support for security legislation to preserve ‘peace and quiet, law and order’ in the nation. (Carlson, 1973: 153) The Act was read in the South African Senate for the first time on 6 June, 1967, and debated from 7 June to 8 June.

Minister of Justice P.C. Pelser introduced the bill to the Senate with an explanation of why the Act was necessary for South Africa’s safety. Pelser opened with an acknowledgement that the Terrorism Act represented a ‘drastic measure,’ yet he offered no ‘excuse’ for the far-reaching nature of the law. (Hansard II of 1967, col. 3761) The Act, he urged, would be the South African government’s response to violent terror and would be a ‘civilized’ response, executed through the courts rather than with force. (col. 3762)

However, Pelser warned that the Senate could not allow for South Africa’s ‘legal machinery to be insufficiently properly streamlined ”¦ to cope with this new phenomenon [of terrorism] effectively’ (3762). Why did Pelser understand further security legislation to be necessary, only one year after the passage of the General Law Amendment Act of 1966? The Minister provided two explanations: first, pre-existing legislation did not allow for the prosecution of those trained before 4 November, 1966, yet South Africa now faced terrorists who had begun their training before that date. (3764) Second, Pelser did not want to root his legal battles against terrorists in the ideological struggle against Communism, a necessary result of prosecution under the Suppression of Communism Act. South Africa had ‘passed the stage of ideological struggle against communism’ Pelser claimed; instead ‘what we are dealing with now is no longer red ideology but red weapons.’ (3765) Pelser recognized that Section Two of the Terrorism Act contained vague crimes but, he asked, ‘if we were to tabulate in the Bill all the possible deeds which could endanger the maintenance of law and order, where would it end?’. (3766) He further denied that one arrested under the act would be ‘presumed guilty’ because the onus of proof fell on the state to prove both that the accused was responsible for deed for which they are charged and that the deed had the effect criminalized in Section Two. (3767-8)

Speaking for the official Opposition Party, Senator R.M. Cadman of Natal gave general support for the bill, and he equated the crime of terrorism with that of treason. (3774) However, he raised two objections to the Act. He took issue with the clause which stipulated that the minimum sentence under the Act would be a five-year prison sentence and he also objected to the unlimited detention period provided for in Section Six. (3775-6)

The Minister of Justice defended the law as he originally introduced it. Pelser argued that a minimum penalty remained necessary on grounds that terrorists knowingly commit murder, and thus deserve, at the least, five year jail terms. He further argued that many other laws have minimum sentences, and this clause keeps the Terrorism Act in accordance with other pieces of legislation. (3781-2)

Pelser went on to defend the unlimited detention of those arrested under the act. Terrorists, he explained, are ‘hardened’ and ‘indoctrinated’ people who will train themselves to hold out for certain lengths of time. Therefore, the Terrorism Act must allow for unrestricted periods of imprisonment ‘for if [terrorists] know that they can be locked up for an indeterminate period for questioning, then they will more easily go over to revealing facts which they would otherwise not do’. (3782).

On the second day of discussion of the act, Senator Cadman made a motion for an amendment to strike the minimum sentence clause. (3841) He focused his critique of the minimum sentence on the vagueness of the Terrorism Act itself, and its pertinence to those not actually performing terroristic deeds. He argued, for example, that someone who possess a firearm (2.1.c) and uses it to cause serious bodily injury (2.2.g) would face a minimum sentence of five years: ‘so if a man were to use a firearm ”¦ for reasons very wide of terrorism,’ for example a farmer against a trespasser, or in a land dispute, or a husband’s ‘emotional’ response to someone’s ‘emotional attachment’ to his wife, that man would face five years in prison if the charge were brought under the Terrorism Act. (3841-2) Though he admitted this might be a rare occurrence, it could result following a mistake by the Attorney General. The possibility of such a case, he urged, would bring South Africa’s justice system into ‘disrepute’ and someone wrongfully convicted might languish in jail for weeks while waiting for a pardon to be secured. (3842-3)

Senator J.L. Horak of the Cape Province concurred with Cadman’s amendment. He argued further that punishments””especially those under laws as vague as the Terrorism Act””should be at discretion of courts. Maintaining a minimum sentence would cast ‘a slur upon [the] Bench’ and indicate a legislative distrust of the South African judicial system. (3845-6) Similarly, Natal Senator G.A. Rall questioned the wisdom of an ‘arbitrarily prescribe[d] ”¦ minimum sentence’ which superseded judges’ decision-making. (3849)

Senators J.J.M. van Zyl of South West Africa and D. G. J. van Rensburg of Orange Free State voiced their support for the minimum sentence clause. The minimum five year jail term, they argued, remained necessary to send a message regarding how South Africa handled terrorists (3843-5) and to present a ‘deterrent to others not to commit this crime.’ (3848)

By a vote of 32-11, the amendment to remove the minimum sentence clause failed (3860), as did a similar motion to strike the minimum five year sentence for those found guilty of harboring or concealing terrorists (Section Three). (3865)

Senators Cadman and Horak put up a similarly doomed fight to alter the indefinite nature of incarceration provided for in Section Six. (3870-3) Senator B.S. de Kok asserted there were ‘certain circumstances in our times, in our legislation, when certain other steps have to be taken.’ Section Six may have been ‘drastic,’ but De Kok saw the clause as necessary for the safety of the Republic. (3873) Van Rensberg and Van Zyl agreed; terrorism was not an ‘individual’ pursuit and the government’s task became impossible if captives had to be released after 14 or 180 days in jail. To Van Zyl, the police had to ‘keep [detained terrorists] until you have caught the whole gang.’ (3877; 3881) Pelser concluded that the recent rise of terrorism meant the government could not rely on the Sabotage Act: ‘We did not realize what we were in for.’ (3884)

The Senate affirmed the Terrorism Act without either of the amendments proposed by Cadman, who stated in a concluding remark: ‘We have our differences in regard to some of the less important aspects of this measure, but, by and large, it is necessary to meet a given situation, and one hopes ”¦ that the time will not be far off when the need for this piece of legislation has gone.’ (3889)

Applying the Terrorism Act

Once adopted, the Terrorism Act was frequently used by security forces to detain a diverse array of people for a variety of crimes. Often, police forces sought to target the activities of particular organizations and conducted wholesale arrests of members and executive officers under the Terrorism Act (Horrell, 1978: 473). Many of the individuals charged under the Act, even those eventually acquitted, faced abuse by police forces during their interim imprisonment.

First Applications

According to the memoirs of anti-apartheid lawyer Joel Carlson, the immediate motivation for the passage of the Terrorism Act were the activities of the South West African People’s Organization (SWAPO); Carlson asserts that, unbeknownst to the population of South Africa, the Act was in fact designed to bring the SWAPO members to trial (Carlson, 1973: 153). In 1966, the government arrested hundreds of members of the organization and almost immediately following the passage of the Terrorism Act, 37 Namibian ‘terrorists’ were brought to trial. The 1967 Act was passed retrospectively, applying to deeds committed since 27 June, 1962 (9.1) so as to apply to the date SWAPO began their training, according to Minister of Justice P.C. Pelser (SAIRR, 1967: 62).

The SWAPO members were charged with engaging in terroristic activities and 32 of the accused pled guilty to this charge. Another three pled guilty only to the alternative charge of serving as members of SWAPO. One man was eventually found not guilty and another died in prison (SAIRR, 1968, 60). 30 members were eventually found guilty of terrorism; the judge sentenced 19 of them to life imprisonment, nine to 20 years, and two others to five year sentences (SAIRR, 1968, 61). 11 of those found guilty appealed their sentence; five of these prisoners had been sentenced for life but a panel of judges reduced their sentence to 20 years (SAIRR, 1968, 62).

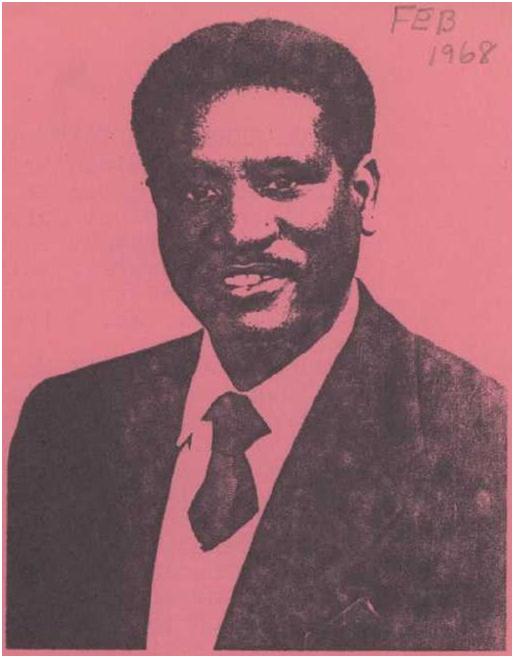

One of the accused SWAPO members, Toivo Herman ja Toivo) (Episcopal Churchmen for South Africa. 1968)

One of the accused SWAPO members, Toivo Herman ja Toivo) (Episcopal Churchmen for South Africa. 1968)

Police beat and abused some of the prisoners. Among those assaulted was Herman ja Toivo who was punched, electric-shocked, and suspended from a pipe until he signed a police-prepared confession. Among those responsible for torturing ja Toivo was the police official Jacobus Swanepoel (Carlson, 1973: 166-168). Another SWAPO member, George””or Gabriel””Mbindi, also faced abuse in prison, though he was most likely imprisoned and charged separately from the 37 others. In advance of a scheduled 20 February hearing to deal with these allegations, police released Mbindi on 16 February and offered him a sum of money, thereby settling the matter out of court and out of the public eye. (SAIRR, 1968, 54, 60-62; Carlson, 1973: 170-171)

Perhaps the first black South African charged under the Terrorism Act was Gideon Mdhletshe. Around August, 1967, the state charged Mdhletshe with assisting others in undergoing military training and for participating in African National Congress(ANC) activities as a member and officer in Durban in 1962 and 1963. Mdhletshe was sentenced to five years in prison. (SAIRR, 1968, 59; American Committee on South Africa, 1968)

Cases and Convictions

Arrests under the Terrorism Act continued throughout the late 1960s and 1970s. In January, 1969 in Pietermaritzburg, twelve alleged terrorist were brought before the Supreme Court, facing charges under both the Terrorism Act and the Suppression of Communism Act. Between June 1962 and November 1968, the state charged, the twelve had plotted alongside 26 co-conspirators to overthrow the Republic. One of the accused was acquitted but the others were found guilty of leaving South Africa with the intention of receiving military training and inciting others to commit terroristic acts. Of the accused, one received a five year sentence, two were sentenced for ten years, the lone female defendant, Dorothy N. Nyembe, received a 15 year sentence, while six others were sentenced for 18 years and one other for 20 years. (SAIRR, 1969: 64)

Reverend Gonville Aubie ffrench-Beytagh

Reverend Gonville Aubie ffrench-Beytagh

One prominent individual arrested under the Terrorism Act was the Anglican Dean of Johannesburg, The Very Reverend Gonville Aubie ffrench-Beytagh. Serving in Rhodesia, from 1954 to 1964, ffrench-Beytagh became known as ‘The Fighting Priest’ for his willingness to publically address race and other issues. (Quinn, 2002; Episcopal Churchmen for South Africa. 1971) When he returned to South Africa in 1965, ffrench-Beytagh refused to remain silent about the injustices of apartheid and he often referred to the segregated ‘South African way of life’ as the ‘South African way of death.’ (Quinn, 2002; ffrench-Beytagh, 85) In the midst of a crackdown on the Church beginning in December, 1970, the Dean was arrested in January, 1971. (Episcopal Churchmen for South Africa; 1971) Security forces detained ffrench-Beytagh under the Suppression of Communism Act after they found ANC and Communist Party leaflets in his apartment, yet the charges were soon thereafter changed to ten counts under the Terrorism Act. In his autobiography, ffrench-Beytagh maintains that the pamphlets, especially those from the Communist Party, were planted in his home. (ffrench-Beytagh, 1973: 138, 147, 156)

Security forces put ffrench-Beytagh through eight days of intense interrogation, often screaming at him: ‘You don’t preach Christianity, you preach shit!’. (ffrench-Beytagh, 1973: 1) A less typical aspect of the Dean’s experience in prison were two visits by British counselor officials, as the state had the right to refuse legal counsel for those imprisoned under the Terrorism Act. (Episcopal Churchmen for South Africa, 1971; ffrench-Beytagh, 1973: 147) Ffrench-Beytagh came to court charged with various counts under the Terrorism Act including: possessing ANC and CPSA pamphlets, encouraging violent revolution in writing and in speeches, assenting to the sending of financial aid to groups intendant on overthrowing the South African State, and discussing various matters relating to terrorism, sabotage, or damaging the South African Republic. (ffrench-Beytagh, 1973: 278-282) On 1 November, 1971 the judge handed down his sentence: five years imprisonment, the minimum sentence under the Terrorism Act. (ffrench-Beytagh, 1973: 229; Quinn, 2002) The Dean’s lawyers appealed the sentence and in April the appeal was accepted. The Dean immediately departed for England (Quinn, 2002; ffrench-Beytagh, 1973: 231-232).

Around 1970, 200 Unity Movement of South Africa (UMSA) members were arrested under the Terrorism Act as part of a nationwide security-forces crackdown on the organization. In 1972, 14 individuals were brought to court in a trial that lasted 18 months; all but one was convicted. Those found guilty faced imprisonments on Robben Island lasting between eight and 21 years (SADET, 2004: 338).

In October, 1973, Nkutsoeu Matsau and six others were arrested in Sharpeville, Vereeniging under the Terrorism Act; by November, Matsau was the only one still in custody (SAIRR, 1974: 82). A member of the Sharpeville Youth Club and the Black People’s Convention(BPC), Matsau was imprisoned for five years for attempting to endanger law and order by writing and possibly handing out copies of a poem entitled ‘Kill, Kill,’ thereby provoking feelings of racial hostility in the Republic (Herbstein, 1979: 78; SAIRR, 1975: 91).

Not every individual charged under the Terrorism Act was convicted. In early 1969, 20 members of the African People’s Democratic Union of Southern Africa (APDUSA) were arrested under the Terrorism Act for leaving South Africa with the intention of undergoing military training. However, by June, 1970 most of the 20 individuals had been released due to lack of evidence against them (SADET, 2004:337).

Similarly, in September, 1969, 21 South Africans, including Winnie Mandela were arrested under the Suppression of Communism Act for participating in ANC activities between 1967 and 1970. On 16 February, 1971, the prosecution withdrew its case, granting the defendants immediate acquittal. However, the accused were instantly re-arrested under the Terrorism Act and charged with almost identical offences, including collaborating with the ANC and CPSA and conspiring to overthrow the government. (Dugard, 1978: 216; Carlson, 1973: 282, 323-324; SAIRR, 1969: 57-65) In their second trial in August-September, 1970, the judge accepted the defendants’ special plea, releasing them and freeing them of all charges. (SAIRR, 1970: 62)

However, even those eventually acquitted could face long periods of detention as they waited for their day in court. Molefe Pheto, an organizer of the ‘Mdali’ ‘Artist Drama Group’ was arrested in March, 1975. Seven months later, on 20 November, he was charged under the Terrorism Act for facilitating the flight from South Africa of an associate who was out of prison on bail. On 10 December, Pheto finally came to trial, and he was acquitted after one day. He later claimed that he had been assaulted by police during his incarceration, which lasted 265 days. (SAIRR, 1976: 133)

Deaths in Detention

Many of those detained under the Terrorism Act, for example George Mbindi, five of those accused alongside Winnie Mandela, as well as Molefe Pheto, alleged that police assaulted or tortured them during their imprisonment. Some charged that they were interrogated non-stop by police for up to three days; others claimed they were beaten by their captors. However, John Dugard notes that some of those detained under the Terrorism Act and assaulted in captivity were ‘unable to tell the[ir] tale themselves and the facts surrounding their deaths ”¦ emerged at inquest proceedings.’ (Dugard, 1978: 135-136) As Denis Herbstein writes, with the implementation of the Terrorism Act South Africa became a place where ‘unknown prisoners died in unnamed gaols on uncertain dates at the hands of the security police.’ (Herbstein, 1979: 36)

Some of those who died while detained under the Terrorism Act were claimed to have committed suicide in prison on their first day of detainment. Such was the case of Jundea Tubakwa who died on 11 September, 1968, as well as Michael Shivute who died on 16 June, 1969. Both men were alleged SWAPO members. (SADET, 2004: 366)

In 1969, three Bakwena tribesmen died in prison following their arrest under the Terrorism Act in 1968. Jacob Monnakgotla, Nicodimus Kgoathe and Solomon Modipane were arrested alongside seven others for attempting to murder the new head of their tribe who had agreed to a relocation plan with the government. The accused appeared in court on 24 January, whereupon the state revoked the charge of murder. However, the accused were immediately rearrested under the Terrorism Act, removing any opportunity to post bail and allowing for indefinite incarceration (SAIRR, 1969, 67).

The ten detainees were scheduled to appear before the Supreme Court in Pretoria on 11 September. On 10 September, however, Jacob Monnakgotla died in his cell, ostensibly from natural causes. However, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission(TRC) later concluded: ‘Monnakgotla was tortured and severely ill treated which resulted in his death.’ His death remained an indicator to the TRC of a ‘gross Human Rights [violation].’(TRC, 1998 ;SAIRR, 1969: 67, 69; SADET: 2004, 366)

Monnakgotla’s tribesman Kgoathe (age 85) entered a hospital in January, 1969 and died there on 4 February. Members of the Security Police stated that Kgoathe had slipped in the shower, though while in the hospital Kgoathe stated that he had been beaten in prison, a story consistent with the pattern of his wounds. The TRC concluded that Warrant Officers F. Smith and J. Venter as well as Detective Sergeant A. De Meyer were responsible for Kgoathe’s death. (SAIRR, 1969, 69; SADET, 2004: 366 ; TRC, 1998)

Modipane suffered a similar fate following his 25 February, 1969 arrest. He died three days later, allegedly due to injuries sustained when he slipped on a bar of soap. However, as with Kgoathe, the TRC found that Modipane’s ‘treatment whilst in custody of the police resulted in injuries which caused his death.’ (SAIRR, 1969: 69; SADET, 2004: 366, TRC, 1998)

Caleb Mayekiso

Caleb Mayekiso

Caleb Mayekiso had been in prison from 1963 until 1967 for allegedly belonging to the ANC. A defendant in the Treason Trial, Mayekiso was free less than a year when he was again arrested, this time under the Terrorism Act, on either 13 or 14 May, 1969. Mayekiso died two weeks later, on 1 June; the District Surgeon confirmed that Mayekiso died of ‘natural causes.’ (SAIRR, 1969: 70, SADET, 2004: 366)

Imam Haron

Imam Haron

On 28 May 1969, police arrested a Cape Muslim leader, Imam Hadja Abdullah Haron for recruiting members to the Pan African Congress (PAC). On 27 September, Imam Haron died in detention, allegedly due to a heart attack. However, an inquest revealed ‘traumatic bruises’ of inconsistent ages on the Imam’s body, casting doubt on the police explanation that Haron had fallen down a flight of stairs eight days prior to his death. The magistrate in the inquest sided with the police’s version of events, stating that while ‘a substantial part’ of the bruises had come from a fall down a flight of stone stairs, he was ‘unable to determine how the balance thereof was caused.’ (SAIRR, 1969: 70, SADET, 2004: 366-377; Haron, 2005)

Mapetla Mohapi

Mapetla Mohapi

In July, 1976 police detained Mapetla Mohapi, a leader of the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM), under the Terrorism Act. Mohapi’s arrest occurred concurrent to the trial of nine South African Student Organization (SASO) and BPC leaders in what one newspaper called the ‘Trial of Black Consciousness’ (SAIRR, 1976: 131). On 5 August 1976, Mohapi was found dead in his cell, hanging by a pair of jeans; police found a note in his cell, addressed to Captain Schoeman of the security police: ‘This is just to say goodbye to you. You can carry on interrogating my dead body. Perhaps you will get what you want from it. Your friend, Mapetla.’ However, a number of factors cast doubt onto the official story that Mohapi committed suicide. A handwriting expert deemed the note a ‘clumsy imitation’ of Mapetla’s hand and the letters he smuggled to his wife written in the days before his death did not, she claimed, carry ‘any desperation or frustration;’ in a later, unrelated, incident a member of the same security police-force, while torturing a South African journalist, placed a wet towel around her neck and stated: ‘Now you know how Mapetla died.’ (Herbstein, 1979: 172; Harrison, 1981: 222-4)

On 18 August, 1977, police arrested Steve Biko, a BPC leader and a founder and organizer of the BCM, outside King William's Town and held him under the Terrorism Act. Around 12 September, 1977, Biko died in captivity, though the exact conditions of his death remain unclear.

Concluding Notes

In 1968, already facing internal and international criticism over the Terrorism Act, the South African government’s Department of Foreign Affairs released a pamphlet South Africa and the Rule of Law defending the Act. The pamphlet argued that South Africa was being unduly criticized as other countries boasted similar laws and ‘South African security legislation can be described as mild in comparison.’ Furthermore, the pamphlet noted the political turmoil of South Africa, thereby justifying the extensive legislation (Quoted in Dugard, 1978: 121).

We will perhaps never know the true extent to which the South African police utilized the Terrorism Act as an implement of repression. Some statistics are available, but they must be interpreted with caution. Often, representatives of security forces claimed they could not release the names or numbers of those imprisoned under the Terrorism Act due to security concerns (see, for example, SAIRR, 1969: 63).

On 3 June, 1969, the Minister of Police stated that, since 12 May, 1969, 35 people had been detained under the Terrorism Act (SAIRR, 1970: 57). One non-official investigation released in 1976 estimated that from the beginning of 1974 to 30 April, 1974, 217 individuals were detained under the Terrorism Act for a total of 22,566 days (an average internment of over 100 days). (Dugard, 1978: 120) Many of those thereafter arrested in the midst of the 1976 Soweto Uprising were detained under the Terrorism Act. (Herbstein, 1979: 23) In 1977, 45 trials were held for 97 individuals charged under the Terrorism Act. By January, 1978, 30 of the cases were still proceeding but of those 15 which concluded: 32 individuals had been acquitted or had their charges withdrawn and 35 had been convicted, for a total sentence of 334 years. (SAIRR, 1977: 131)

In 1982, the South African government passed a new, all-encompassing piece of security legislation, the Internal Security Act of 1982 which incorporated much of the Terrorism Act and the Suppression of Communism Act. Correspondingly, the Internal Security Act repealed all of the Terrorism Act, with the exception of Section Seven, which restated the power of the judiciary over those arrested by security forces. The Internal Security Act was repealed on 11 November, 1993.

This article was written by Jonathan Cohen and forms part of the SAHO Public History Internship