In the first quarter of this year South Africa’s normally staid and insignificant mask industry exploded.

Like its peers across the globe it had orders pouring in from the original epicentres of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Locally, a layer of parasitic middlemen sprang up overnight. One local manufacturer contacted by amaBhungane requested anonymity on the unusual basis that being named in the media would exacerbate the unbearable deluge of new business coming their way.

There had already been enquiries he could not fulfil in his lifetime, with traders queuing at the door, he said

“If you put out an email to say you had a 100-million FFP2s on hand, by Friday you wouldn’t have one left. Before that you were lucky to do five million a year.”

FFP2 is the European equivalent of the American N95 or Chinese KN95, a measure of a mask’s ability to block particles.

Local hoarding and price gouging have been rampant but pale in comparison to the major initial pull of market forces: exports.

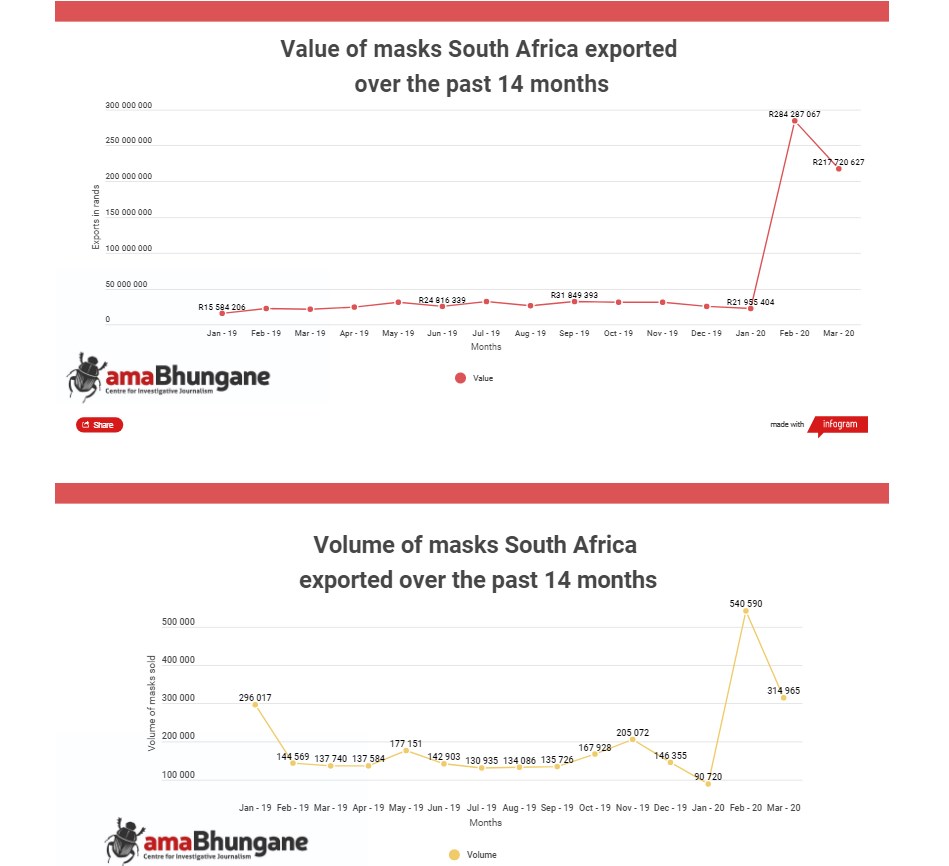

Customs data released by the department of trade, industry and competition shows a spectacular surge starting in January and continuing into the state of disaster declared in March.

As a baseline, back in the first quarter of 2019 South Africa exported medical and industrial face masks worth roughly R58-million.

Fast forward to the first three months of 2020 and exports were worth nearly ten times that, R524-million to be exact.

Trade, Industry and Competition Minister Ebrahim Patel banned these exports effective 27 March, when the lockdown started.

Other goods covered by Patel’s export ban include hand sanitiser – but also less obvious things, like a variety of vaccines and the malaria drug hydroxychloroquine, infamously punted as a “game changer” by US president Donald Trump.

How many masks are we talking about?

The answer is “a lot” even though it is hard to put a number on it. A large part of the surge in export value reflects an increase in prices fetched in global markets, not volumes.

In official customs data the amount exported increased from around 580 000 units to about 950 000 units, largely to China and the United Arab Emirates.

A unit is not a mask but a box of masks, meaning that the exports were multiples of the 950 000 units. So millions of masks left the country. It is however still hard to say how many masks there are in a box.

The data covers at least three types of mask.

These are the standard 3-ply disposable medical masks, the more durable but still disposable N95 masks, as well as non-disposable gas masks with changeable filters.

All three types of masks were targeted by Patel for his partial export ban.

Before the ban the combined exports looked like this:

The medical masks are generally sold in units of fifty while the N95s are sold in tens while the gas masks are sold as single items.

The trade statistics mix these together. If the exports for the first quarter this year were made up entirely of N95 masks you would for instance get about 10-million masks being exported. If it was all medical masks, then about 50-million were exported.

It’s worth keeping these numbers in mind now that South Africa has turned around to instead become a desperate importer of personal protective equipment (PPE).

The major private sector import initiative has been under the umbrella of Business for South Africa (B4SA), underpinned by the immense pooled resources of the Solidarity Fund, Motsepe Foundation, FirstRand’s SPIRE Fund and Naspers.

It had an order book of R1.1-billion for imported PPE as of 15 May. This included 12-million N95 masks and 38.2-million medical masks (as well as gloves, aprons, hand sanitisers, goggles, gowns and ventilators).

In other words, the mask imports being organised after Patel’s ban very roughly match the exports up to Patel’s ban.

“B4SA is working to help fulfil the country’s emergency phase needs for PPE, and hopes to help stabilise stocks by the end of May.

“Following this, B4SA will continue to secure stock on a month by month basis. As local capacity to produce products in South Africa increases, we will continue to shift our sourcing strategy to the local market,” B4SA said by email.

If South Africa had not imposed export controls, it is unlikely that any masks would stay in the country.

You can currently sell N95 masks internationally for up to $7 (R130) each.

Once Patel’s department stopped exports on 27 March, national treasury could safely create a price list applying to the public sector.

The maximum price payable for N95 masks is R37.80 each. For medical masks it is R10.22 and for surgical masks R12.48.

The last two are cheaper to make and also have to be disposed of every few hours while the N95s last longer and are more difficult to manufacture.

These prices are significantly less than what manufacturers and traders could get in the international market. But the local prices remain significantly higher than before Covid-19.

The extent of the initial price gouging in South Africa was astonishing.

Private hospital group Mediclinic told amaBhungane that it saw some suppliers inflate prices to 20 times normal levels before negotiations brought them back down. At the group’s hospitals the pandemic has seen the use of masks double or even triple.

The Competition Commission has received 1 354 complaints related to price gouging since the beginning of the state of disaster on 17 March. Of these, 164 complaints related to masks.

A presentation it gave this week to the parliamentary committee on trade and industry related these examples:

Babelegi Workwear Overall Manufacturers & Industrial Supplies in Centurion hiked the price of facial masks from R41 to R500 per box. Hennox Supplies and Sicuro Safety hiked prices for FFP1 masks tenfold. FFP1 masks are a lower grade mask not suited for medical use.

Dischem stores hiked prices for surgical masks between 46% and 261%.

The National Consumer Commission has referred more cases to the Competition Tribunal and dozens of investigations are ongoing.

Price increases have been underpinned by the instantaneous rise of a new cohort of traders – mask dealers who never previously had anything to do with the industry. The commission noted the rise of “opportunistic trading through various platforms, such as existing retail channels, direct sales to the public or online platforms of items that were not previously traded with huge mark-ups”.

Said the local manufacturer: “I think the problem in the industry now is that that this whole mask thing has just become a trader’s dream… We are trying our very best not to deal with traders at all.”

Companies that have never had anything to do with PPE have suddenly changed course to become intermediaries for local and foreign producers.

One local dealer in car parts now sells a whole range of Covid-19 supplies including N95 and 3-ply medical masks in lots ranging from 10 to 10 000. Another company previously a supplier of homecare furniture and wheelchairs, now sells masks on Gumtree.

Online marketplaces like BidorBuy, OLX, Loot.co.za and the international behemoths Amazon and Alibaba are brimming with mask ads.

The Competition Commission has set down strict guidelines to combat price gouging during the pandemic.

The general rule is that there cannot be a sudden and huge increase in the profit margins tied to essential products. In the manufacturer’s view this simply opens the door to the parasitic middle layer of traders.

“Most of the manufacturers…you’d be lucky to get to R18 per mask based on the criteria one would have to apply for the [Competition Commission].”

“For exports you are selling at R45 per mask, in dollars. So you are selling at $2.40 or $2.50. $2.20 worse-case scenario.

“Then you have the government now who are happy to pay anything between R45 and R55 but here is the catch. Effectively [to avoid allegations of price gouging] you’ve got to sell it to a trader who is going to mark it up to R55 and sell it into government. The company that has invested in the past does not get any of that upside.”

New traders have no prior price history which makes it easier for them to get away with high mark-ups.

The new national price ceiling of R37.80 imposed in the public sector forces these levels down somewhat.

Another new problem has emerged which is that suspicious suppliers are entering the international supply chain and passing off inferior masks as ones meeting the international N95 benchmark.

Mediclinic mentioned that it now needs to do extra validations on supplies from new sources to confirm quality. The manufacturer we spoke to raised the same concern.

This might become a systemic problem.

South Africa is falling victim to a less-known global shortage: the near-exhaustion of supply of spun-bond, a material used for the crucial middle layer in medical and N95 masks.

These masks have three layers and it is the spun-bond that actually stops particles and differentiates medical grade masks from the cloth masks most South Africans now wear.

It is not made locally and availability has dropped off a cliff.

South African imports of the material dropped from about 446 tons in February to 182 tons in March during a period of massive demand growth.

The numbers for April are not in yet but our overworked mask-maker says you cannot get the stuff anywhere anymore.