Yohannes Woldemariam trawls through the history books to expose the truths of Haile Selassie’s 44-year reign over Ethiopia.

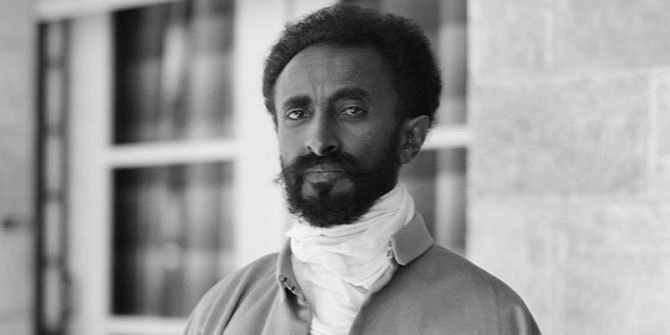

Emperor Haile Selassie, who ruled Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974, died in 1975, but he lives on through the romantic lyrics of the late Jamaican reggae star Bob Marley and Ethiopian pop star, Tewedros Kassahun, better known as Teddy Afro.

Yet there is a wide range of views of the man whose full official title was: “His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I, Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah, King of Kings and Elect of God.” Some remember him as a benevolent ruler who resisted Italian colonisation. For others, he is a god, yet others view him as a tyrant.

Marley’s portrayal of Selassie is strongly influenced by the Rastafarian belief that he is God incarnate, as allegedly “prophesied” by Marcus Garvey. On the other hand, Teddy Afro, an Ethiopian, is promoting his version of Ethiopianism (Ethiopiawinet).

The Kebra Nagast (also known as the Glory of Kings) is the ancient text from which Selassie’s mythology stems. It narrates the relationship between King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba and their son Menelik I, who allegedly hid the Ark of the Covenant in Ethiopia. Like Menelik II (1889-1913), Haile Selassie, a distant relation, claimed descent from the Solomonic dynasty. Inspired by this ideology, Ethiopian kings and emperors have conquered lands and enslaved ethnic groups. In this sense, the Kebra Nagast can fairly be compared to the 19th century expansionist white American ideology of the Manifest Destiny.

Those who have solely learned about Selassie through the music of reggae stars and Teddy Afro may well have developed the impression that Selassie was a fatherly benevolent ruler and a champion of blacks. However, this portrayal of Selassie and his predecessor, Emperor Menelik II, is grossly distorted. Clearly, even though the last Ethiopian monarch was overthrown in 1974, undercurrents of the Kebra Negast still reverberate in the discourse of Ethiopian nationalism. While the majority of the Ethiopian people do not subscribe to this belief system, some Ethiopians look for aspects of the Kebra Nagast narrative for Ethiopiawinet. Yet this mythology, or elements of it, creates huge divisions through its implicit expectation that Ethiopians accept this version of identity politics.

Rastafarian representation of Selassie

For Rastafarians, Ethiopia is Zion and the Promised Land and in 1948 Selassie granted them land in the Rift Valley for a settlement in Shashemane. The settlement has never been big, with no more than a thousand Rastas at its peak and now about 400. There was never a mass exodus of Rastas to Ethiopia, and they never assimilated. They live in isolation much like the Amish in the United States.

The Rastafarian connection with Selassie is made with a tenuous understanding of Jamaican Pan Africanist Marcus Garvey’s famous prophecy: “Look to Africa, when a black king shall be crowned for the day of deliverance is near!” This reference to “Africa” was reinterpreted to mean Ethiopia and the link to “a black king” was the coronation of Selassie in 1930. The travel writer Bill Wiatrak claims that the Rasta movement originated in Ethiopia but it actually began in Jamaica through the misinterpretation of Garvey’s message.

condemned him as a “great coward” for fleeing Mussolini’s troops in 1935, when Italy invaded Ethiopia. He also criticised Selassie’s practice of slavery, which was not abolished in Ethiopia until 1942. In Garvey’s own words:

It is preferable for the Abyssinian Negroes and the Negroes of the world to work for the restoration and freedom of the country without the assistance of Selassie, because at best he is but a slave master. The Negroes of the Western World whose forefathers suffered for three hundred years under the terrors of slavery ought to be able to appreciate what freedom means. Surely they cannot feel justified in supporting any system that would hold their brothers in slavery in another country whilst they are enjoying the benefits of freedom elsewhere. The Africans who are free can also appreciate the position of slaves in Abyssinia [Ethiopia]. What right has the Emperor to keep slaves when all the democratic sections of the world were free, when men had the right to live, to develop, to expand, to enjoy all the benefits of human liberty? (1937, p.741).

While few reggae aficionados realise the wide gulf between Selassie’s mythological representations in popular culture and the reality of his tyrannical reign, the perception that Selassie was a proud African and a champion for black people is not supported by the facts. He only reluctantly later embraced the Rastafarians because he understood their public relations value for his cult of personality. Some of his dedicated followers would be dismayed to learn that Selassie revered not his “own people” but the Ferenjochu (Europeans) and Americans, who were routinely invited to his lavish parties in his palace.

His overthrow in 1974 and subsequent death caused “a crisis of faith” in Jamaica among the followers of the Rastafarian faith. The religion does not accept the former emperor’s death and instead depicts it as a “disappearance” similar to the belief held by the Shiite branch of Islam when “the Hidden” Imam Hussayn was martyred in the seventh century. Bob Marley’s 1975 song called Jah Live seeks to refute the fact of Selassie’s death by insisting that a deity could not have died.

Teddy Afro and his reverence for Ethiopian monarchs

Teddy Afro stylistically mimics Bob Marley when singing the praises of Selassie and even of Menelik II who claimed to be a descendent of Menelik I. In his songs, Teddy Afro proclaims unity and love for all Ethiopians. It is worth asking how Ethiopian unity is served by his praise for these monarchs. If his objective is to promote a unified pan-Ethiopian nationalism, it seems to have backfired by provoking ethnic nationalism among the Oromo who do not share similar conceptions of these rulers – and rather view them as the reason for their oppression and suffering. A selective reading of history does little to build a strong national foundation. Rather, a new social contract is desperately needed which respects the pluralism and diversity of the country.

Historical accounts of the reign of Menelik II show him as contemptuous of blackness, an expansionist, an enslaver and cruel. As a case in point, Eritreans made important, though little-acknowledged contributions to the Ethiopian victory over the Italian colonisers in Adwa in 1896 by gathering crucial intelligence on Italian war strategy. Emperor Menelik II returned the favour by savagely amputating the arms and legs of Eritrean war prisoners. Never mind that these poor Eritrean peasants were violently forced to fight under Italy, just as other European colonialists used Africans, Indians and other colonial subjects as cannon fodder for their wars of conquest everywhere. Nevertheless, Menelik II, the so-called “champion of a black victory,” decided to set free his Italian and Libyan war prisoners while mutilating the Eritreans.

In fact, Menelik II’s reconstructed image as a historical agent of black liberation does not fit recorded events. For instance, his state of mind was revealed through a comment to a Haitian dignitary that he did not consider himself to be a black man. Therefore, Teddy Afro’s celebration of Menelik as the “Tikur Sew” (“Black Man”) lacks historical basis. Invoking Selassie or Menelik II as Teddy Afro does polarises communities because it insults those who do not share this interpretation of history and the terrible legacy of these monarchs.

Haile Selassie as an international statesman

It should be noted that Haile Selassie’s global prominence was due to his position as a very loyal client of the West – much like the Shah of Iran and Mobutu of Zaire. These clients maintained power through repression and the murder and silencing of true patriots. Unlike Selassie however, history accurately remembers Shah Reza Pahlavi and Mobutu Sese Seko as tyrants. Yet, efforts are underway to depict Selassie as a pan-Africanist and a visionary. Some have campaigned vigorously for his statue to be erected in front of the African Union building in Addis Ababa. Sadly, the African Union has acceded to the request.

Selassie often took undeserved credit for others’ contributions. One example was Lorenzo Taezaz, an Eritrean, who enhanced Selassie’s image during the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. While the emperor was in exile in Bath, England, Taezaz secretly slipped into Ethiopia and organised the Arbeghoch (patriots). He recruited 2,000 or so Eritreans who had fled Italian colonial rule to fight for Ethiopia from their refugee settlements in Kenya. He also smuggled weapons for the Arbegnoch. A famous speech delivered by Selassie, famed for developing his aura as statesman and defender of his people, at the League of Nations in 1936, is widely believed to have been written by Taezaz. The emperor eventually repaid Taezaz by demoting him from his position as Foreign Minister. He died soon after in 1947 in suspicious circumstances.

Selassie “demonised as a dictator”

Does Selassie deserve to be depicted as a dictator? The historical record provides a decisive answer.

First, it is well-established that he spent $35 million for celebrating his 80th birthday during the Wollo famine. He travelled widely, visiting the United States many times, only stopping once in Jamaica in 1966.

Perhaps less well-known are Selassie’s crimes and his associates, such as Asserate Kassa in Eritrea. These are too numerous and ghastly for the scope of this piece. For further reading on this, I recommend Michela Wrong’s book titled I Didn’t Do it For You. How the World Betrayed a Small African Nation.

Similarly, the autocrat is remembered in Tigray for inviting the British Royal Air Force to bomb the region in 1943 to quell what came to be known as the first Woyane Rebellion. He consolidated his power by weakening the provinces after Italy’s defeat by the British in 1941.

He was also harsh towards those Ethiopian patriots who fought against the Italians while he fled to Britain. For example, Belay Zeleke, a national war hero was hung on his orders. Unfathomably, Teddy Afro recently praised both Selassie and Belay Zeleke during an appearance at the Millennium Hall in Addis with the Eritrea President Isaias and Ethiopia PM Abiy in the audience. It seems unconscionable to praise a murderous traitor and his victim, too. The parable of Polish writer Ryszard Kapuscinski: The Emperor, Downfall of an Autocrat is an accurate depiction of the real Selassie.

Why bother with Selassie at this time?

The romantic rewriting of Selassie’s legacy, and the distorted history of other Ethiopian monarchs have significant relevance for current Ethiopian politics. Selassie’s legacy needs to be exposed in light of attempts by musicians, historical revisionists in the diaspora, foreign beneficiaries and politicians to control the narrative through false representations.

This cannot be dismissed as benign and harmless because of the role music plays in creating what the theorist of nationalism, Benedict Anderson, calls ‘imagined communities’ and its crucial role in political organising. Music heightens and releases endorphins creating a sense of belonging among people with shared sentiments which can lead to collective action. The misplaced form of black nationalism created by Rastafarians, in giving reverence to a man who never deserved it, is therefore harmful.

Still, I celebrate the addition of reggae to UNESCO’s ‘Intangible Cultural Heritage’ list while taking exception to the claim: “its contribution to international discourse on issues of injustice, resistance, love and humanity underscores the dynamics of the element as being at once cerebral, socio-political, sensual and spiritual.” The record of reggae is rather more nuanced and mixed, particularly in reference to the place given to Selassie.

It is often said that the victors or the powerful are the ones who write history. History is ill served when popular celebrities and musicians motivated by religion or some kind of hyper-nationalism misrepresent the past. This is offensive to the victims and divisive for communities who need genuine solidarity.